Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Neurotoxic Poisons: Somniferous Drugs

Opium: Diagnosis, Treatment, Autopsy Features, Forensic Issues - Somniferous Drugs(Narcotics) Neurotoxic Poisons

Diagnosis

·

Needle marks, dermal scars

(suggestive of addiction).

·

Evidence of hypoglycaemia, hypoxia,

and hypothermia.

·

Most opiates can be detected in

urine or blood by RIA, GC, GC-MS, or HPLC.

·

Empirical administration of

naloxone, (can precipitate reaction in

addicts).

Treatment

Acute Poisoning:

a.

Supportive measures—

–– Maintenance of patent airway.

–– Endotracheal intubation, assisted

ventilation: Maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation with frequent

monitoring of arterial blood gases and/or pulse oximetry. If a high FIO2

is required to main- tain adequate oxygenation, mechanical ventilation and

positive-end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may be required; ventilation with small

tidal volumes (6 ml/kg) is preferred if ARDS develops. Crystalloid solutions

must be administered judiciously. Pulmonary artery monitoring may help. In

general the pulmonary artery wedge pressure should be kept relatively low while

still maintaining adequate cardiac output, blood pressure and urine output.

–– Ipecac-induced emesis is not recommended

because of the potential for CNS depression and seizures.

–– Consider prehospital administration of

activated charcoal as an aqueous slurry in patients with a potentially toxic

ingestion who are awake and able to protect their airway. Activated charcoal is

most effec- tive when administered within one hour of ingestion.

b. Naloxone is the antidote of choice for opiate

poisoning,.

c. The use of physostigmine salicylate (0.04

mg/kg IV)has been suggested for reversing respiratory depression if the regular

opiate antidotes are not available, since it increases the acetylcholine

content of the reticular formation of the brainstem which is suppressed by

opiates. However, there is controversy regarding such a measure since

physostigmine (unlike regular opiate antagonists) is a dangerous antidote with

serious adverse effects.

Antidotes for opiates

Naloxone—

It is effective against all opiates including pentazocine, but is not

very effective against buprenorphine. Dramatic reversal of the following

features is achieved: miosis, respiratory depression, hypotension, coma.

Dose: The usual initial dose is 1.2 mg for an adult and 0.4 mg for a

child. The best route of administration is IV, but if venous access is

difficult, the drug can be injected sublingually or intramuscularly, or even

instilled down an endotracheal tube. Since the effect of a single bolus dose of

naloxone is usually short-lived, repeated doses are required. Repeat doses of 2

mg may be given to achieve a clinical effect. Generally, if no response is

observed after 10 mg has been administered, the diagnosis of opiate-induced

toxicity should be questioned. Very large doses of naloxone (10 mg or more) may

be required to reverse the effects of buprenorphine overdose. Some

investigators state that a naloxone infusion is better than repeated

injections. The following steps are suggested:

·

Determine the maintenance fluid requirement for

24 hours.

·

To determine the amount of naloxone (in mg) to

add to the maintenance fluid for a 24-hour period, take the bolus dose required

for initial response (in mg) and multiply by 2/3 and 24 (hrs).

·

To determine the desired rate of infusion

(ml/hr), take the maintenance fluid, and divide by 24 (hrs)

This method is said to reduce the risk of possible fluid overload and

pulmonary oedema. A continuous infusion of naloxone is espe-cially useful in

circumstances of opiate overdose with long acting opiates. Naloxone can be

diluted in normal saline or 5% dextrose, but should not be added in alkaline

solutions. Any prepared solution of naloxone should be used up in 24 hours.

Caution should be exercised in reversing opiate toxicity in addicts because of

the risk of precipitating withdrawal reaction. Observe patients for evidence of

CNS or respiratory depression for at least 2 hours after discontinuing the

naloxone infusion.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a neonatal dose of 0.1

mg/kg intravenously or intratracheally from birth until age 5 years or 20 kg

body weight.

Naltrexone—

Naltrexone is a long-acting opiate antagonist which can be administered

orally. It is usually used for treating opiate addiction. However, it must not

be given to an opiate-dependant patient who has not been detoxified. A

challenge dose of naloxone to confirm the lack of opiate dependence is

recommended before beginning naltrexone.

Dose: 50 mg/day orally, which may have to be continued for several weeks

or months.

Nalmefene—

Nalmefene is a naltrexone derivative with pure opiate antagonistic

effects, and has a longer duration of effect than naloxone in acute opiate

poisoning. It is usually given intravenously beginning with 0.1 mg, and if

withdrawal reaction does not occur, 0.5 mg is admin-istered, followed by 1 mg

in 2 to 5 minutes (if necessary). Nalmefene can also be given intramuscularly

or subcutaneously

d. The use of drugs such as levorphanol and amiphena-zole is

no more recommended today.

e. Convulsions may be treated with benzodiazepines in the

usual manner (5 to 10 mg initially, repeat every 5 to 10 minutes as needed),

though this is frequently not necessary if naloxone is available. Monitor for

respira-tory depression, hypotension, arrhythmias, and the need for

endotracheal intubation. Evaluate for hypoxia, electrolyte disturbances, and

hypoglycaemia (or treat with intravenous dextrose 50 ml IV in an adult, or 2

ml/ kg in 25% dextrose for a child).

f.

For hypotension: Infuse 10 to 20 ml/kg of

isotonicfluid and place in Trendelenburg position. If hypoten-sion persists,

administer dopamine (5 mcg per kg per min, progressing in 5 mcg per kg per min

increments as needed), or noradrenaline (0.5 to 1 mcg per min, and titrate to

maintain adequate blood pressure). Consider central venous pressure monitoring

to guide further fluid therapy.

g. Prevention

of rhabdomyolysis: Early aggressivefluid replacement is

the mainstay of therapy and may help prevent renal insufficiency. Diuretics

such as mannitol or furosemide may be needed to maintain urine output. Urinary

alkalinisation is not routinely recommended.

Chronic Poisoning:

·

Gradual withdrawal of the opiate.

·

Substitution therapy with methadone

begun at 30 to 40 mg/day and then gradually tapered off.

·

A beta adrenergic blocker like

propranolol (80 mg) is said to be quite effective in relieving the anxiety and

craving associated with opiate addiction, but has no effect on physical

symptoms. Alternatively, drugs such as clonidine can be used. Buprenorphine or

naltrexone can also be used. Recent reports suggest favourable outcome with

gabapentin combined with clonidine and naltrexone. The regimen suggested is

clonidine 0.1 mg thrice a day for 7 days, followed by naltrexone 50 mg twice a

day for 14 days, along with gabapentin 600 mg twice a day on all the 21 days.

·

Antispamodics for abdominal cramps

associated with vomiting and diarrhoea.

·

Tranquillisers or bed time sedation

if necessary.

·

Psychiatric counselling.

Autopsy Features

·

Injection marks, dermal abscesses,

scarring. Look for injec-tion marks in the antecubital fossae, forearms, back

of the hands, neck, groin, and ankles.

·

Tattooing, (a common feature of the

drug sub-culture).

· Emaciation, unkempt appearance.

· Gross pulmonary oedema with froth

exuding out of mouth and nostrils, especially in sudden heroin-related death.

·

Another frequent autopsy finding in

heroin fatalities is undiagnosed pneumonia.

·

Autopsy findings of heroin-induced

spongiform leukoen-cephalopathy include spongiform degeneration of white

matter, vacuolisation and fluid accumulation in myelin sheaths.

·

Cerebral oedema.

·

Congestion of liver with enlargement

of hepatic lymph nodes. Chemical analysis of lymph nodes may reveal pres-ence

of morphine.*

·

Myocardial damage, with focal

lesions formed by small mono-nuclear inflammatory cells and with degenerated,

necrotic myocardial fibres and congestion, has been shown to occur as a result

of prolonged hypoxic coma following opiate intoxica-tion.

·

Samples of blood, urine, brain,

liver, and bile must always be preserved for chemical analysis.

·

It is important to remember that

infections such as serum hepa-titis and AIDS are common among intravenous drug

abusers, and hence autopsies conducted in drug-related deaths must be done

cautiously with necessary precautions.

Forensic Issues

· Opiates are among the commonest of

the drugs abused today in India. Heroin (brown

sugar) is popular among all classes of addicts in metropolitan cities such

as Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore, etc. Opiates used for therapeutic purposes, e.g.

morphine, pethidine, and pentazocine are more commonly abused by medical and

paramedical personnel. Buprenorphine is emerging as a major drug of abuse even

among non-medical personnel in recent times. Codeine which is easily available

over the counter in the form of antitussive preparations is being increasingly

abused especially by college-going youth.

· Accidental deaths are not infrequent

from overdose, particu-larly among intravenous abusers of heroin (“death on the

needle”). Wound botulism, which has been associated with subcutaneous or

intramuscular black tar heroin injections, has caused potentially lethal,

descending, flaccid paralysis when Clostridium

botulinum spores germinated in wounds, releasing neurotoxins.

· “Cotton fever” is common among IV

abusers, which is a febrile reaction that develops because these drugs are

often filtered through cotton balls prior to being injected.

·

Chronic parenteral opiate abuse can result in abscesses,

acute transverse myelitis, anaphylaxis, AIDS, arrhythmias, wound botulism,

cellulitis, endocarditis, faecal impaction, glomerulonephritis, hyper or

hypoglycaemia, osteomyelitis, post-anoxic encephalopathy, tetanus,

thrombophlebitis, nephropathy, hoarseness, hepatitis, pneumothorax, para-plegia,

mycotic aneurysms, or leucoencephalopathy.

· Suicidal deaths are also reported

from time to time since opiates are reputed to cause a painless death.

Homicides are rare, but a few cases have been documented in medical literature.

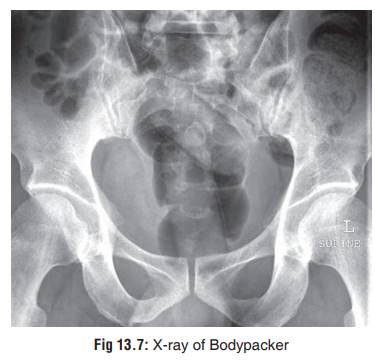

· Body Packer Syndrome—Although this is more

commonlyassociated with smuggling of cocaine, it has also been reported in the

case of other drugs, especially heroin.

o

A “bodypacker” or “mule” is an individual who attempts to

transport illicit drugs from one country to another by ingesting wrapped

packages, or condoms (Fig 13.6), or

balloons containing concentrated cocaine or heroin. After arrival at the

destination, cathartics are self-administered and the packets are defaecated

out. Sometimes rectal suppositories or disposable enemas are used.

o

Although generally asymptomatic, in a few cases serious

toxicity may result due to rupture of packets. Death due to intestinal

obstruction and perforation has been reported in heroin body packers.

o

Diagnosis of an asymptomatic body packer can be accomplished

with the help of an abdominal X-ray (Fig13.7),

ultrasound, or CT scan. The last two methodsshould be resorted to only if X-ray

is unclear. In some cases, faecal examination over a period of a few days may

be necessary. Magnetic resonance does not visualise packets because of the lack

of protons.

o Asymptomatic patients should be treated by whole bowel irrigation with polythylene glycol solution. However some investigators do not approve of this method since the polythylene glycol can dissolve the heroin from a package, rupturing it and increasing absorption of heroin. Instead, a period of waiting is recommended so that all packages pass into the colon from the stomach, and then low-volume phosphosoda enemas or high-volume saline enemas are administered. Food ingestion must not be permitted until all packages have moved into the colon. Metoclopramide 10 mg, 8th hourly, may be administered to encourage gastric emptying. Bowel obstruction must be ruled out. It may be advisable to empty the rectum first by a bisacodyl suppository.

·

Symptomatic patients must be managed with

contin-uous-infusion naloxone, activated charcoal, and whole bowel irrigation.

Intestinal perforation or obstruction by packets requires surgical

intervention.

Related Topics