Chapter: Introduction to the Design and Analysis of Algorithms : Space and Time Trade-Offs

Open and Closed Hashing

Hashing

In this section, we consider

a very efficient way to implement dictionaries. Recall that a dictionary is an

abstract data type, namely, a set with the operations of searching (lookup),

insertion, and deletion defined on its elements. The elements of this set can

be of an arbitrary nature: numbers, characters of some alphabet, character

strings, and so on. In practice, the most important case is that of records

(student records in a school, citizen records in a governmental office, book

records in a library).

Typically, records comprise

several fields, each responsible for keeping a particular type of information

about an entity the record represents. For example, a student record may

contain fields for the studentŌĆÖs ID, name, date of birth, sex, home address,

major, and so on. Among record fields there is usually at least one called a key

that is used for identifying entities represented by the records (e.g., the

studentŌĆÖs ID). In the discussion below, we assume that we have to implement a

dictionary of n records with keys K1, K2, . . . , Kn.

Hashing is based on the idea of

distributing keys among a one-dimensional array H [0..m ŌłÆ 1] called a hash table. The

distribution is done by computing, for each of the keys, the value of some

predefined function h called the hash

function. This function assigns an integer between 0 and m ŌłÆ 1, called the hash address, to a key.

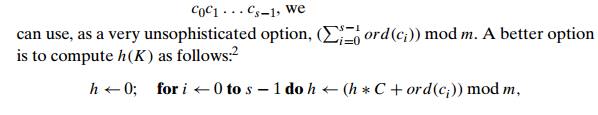

For example, if keys are nonnegative integers, a hash function can be of the form h(K) = K mod m; obviously, the remainder of division by m is always between 0 and m ŌłÆ 1. If keys are letters of some alphabet, we can first assign a letter its position in the alphabet, denoted here ord(K), and then apply the same kind of a function used for integers. Finally, if K is a character string

where C is a constant larger than every ord(ci).

In general, a hash function

needs to satisfy somewhat conflicting require-ments:

A hash tableŌĆÖs size should

not be excessively large compared to the number of keys, but it should be

sufficient to not jeopardize the implementationŌĆÖs time efficiency (see below).

A hash function needs to distribute keys among the cells of the hash table as evenly as possible. (This requirement makes it desirable, for most applications, to have a hash function dependent on all bits of a key, not just some of them.)

A hash function has to

be easy to compute.

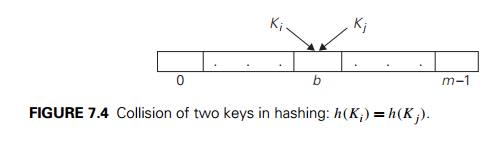

Obviously, if we choose a hash

tableŌĆÖs size m to be smaller than the

number of keys n, we will get collisionsŌĆöa

phenomenon of two (or more) keys being hashed into the same cell of the hash

table (Figure 7.4). But collisions should be expected even if m is considerably larger than n (see Problem 5 in this sectionŌĆÖs exercises).

In fact, in the worst case, all the keys could be hashed to the same cell of

the hash table. Fortunately, with an appropriately chosen hash table size and a

good hash function, this situation happens very rarely. Still, every hashing

scheme must have a collision resolution mechanism. This mechanism is different

in the two principal versions of hashing: open hashing (also called separate

chaining) and closed hashing (also called open

addressing).

Open

Hashing (Separate Chaining)

In open hashing, keys are

stored in linked lists attached to cells of a hash table. Each list contains

all the keys hashed to its cell. Consider, as an example, the following list of

words:

A, FOOL, AND, HIS, MONEY, ARE, SOON, PARTED.

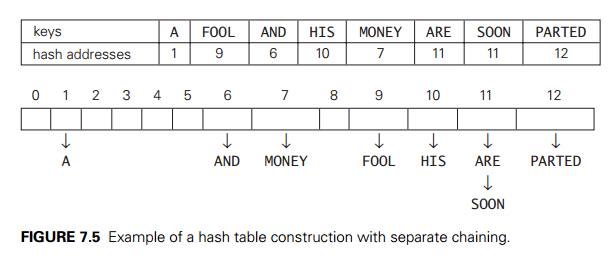

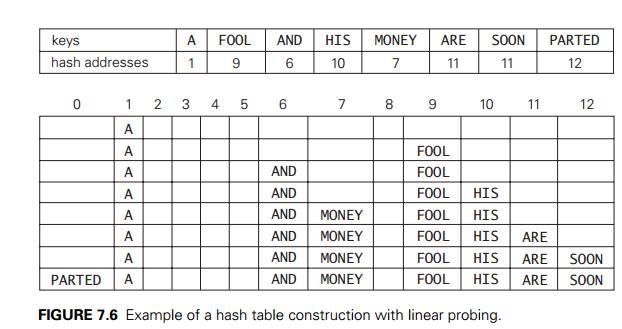

As a hash function, we will

use the simple function for strings mentioned above, i.e., we will add the

positions of a wordŌĆÖs letters in the alphabet and compute the sumŌĆÖs remainder

after division by 13.

We start with the empty

table. The first key is the word A; its hash value is h(A) = 1 mod 13 = 1. The second keyŌĆöthe word FOOLŌĆöis installed in the ninth cell since (6 + 15 + 15 + 12) mod 13 = 9, and so on. The final result of this process

is given in Figure 7.5; note a collision of the keys ARE and SOON because h(ARE) = (1 + 18 + 5) mod 13 = 11 and h(SOON) = (19 + 15 + 15 + 14) mod 13 = 11.

How do we search in a

dictionary implemented as such a table of linked lists? We do this by simply

applying to a search key the same procedure that was used for creating the

table. To illustrate, if we want to search for the key KID in the hash table of Figure

7.5, we first compute the value of the same hash function for the key: h(KID) = 11. Since the list

attached to cell 11 is not empty, its linked list may contain the search key.

But because of possible collisions, we cannot tell whether this is the case

until we traverse this linked list. After comparing the string KID first with the string ARE and then with the string SOON, we end up with an

unsuccessful search.

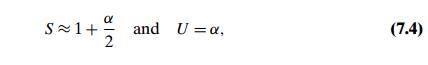

In general, the efficiency of

searching depends on the lengths of the linked lists, which, in turn, depend on

the dictionary and table sizes, as well as the quality

of the hash function. If the

hash function distributes n keys among m cells of the hash table about evenly, each

list will be about n/m keys long. The ratio ╬▒ = n/m, called the load

factor of the hash table, plays a crucial role in the efficiency of

hashing. In particular, the average number of pointers (chain links) inspected

in successful searches, S, and unsuccessful searches, U, turns out to be

respectively, under the standard

assumptions of searching for a randomly selected element and a hash function

distributing keys uniformly among the tableŌĆÖs cells. These results are quite

natural. Indeed, they are almost identical to searching sequentially in a

linked list; what we have gained by hashing is a reduction in average list size

by a factor of m, the size of the hash table.

Normally, we want the load

factor to be not far from 1. Having it too small would imply a lot of empty

lists and hence inefficient use of space; having it too large would mean longer

linked lists and hence longer search times. But if we do have the load factor

around 1, we have an amazingly efficient scheme that makes it possible to

search for a given key for, on average, the price of one or two comparisons!

True, in addition to comparisons, we need to spend time on computing the value

of the hash function for a search key, but it is a constant-time operation,

independent from n and m. Note that we are getting this remarkable

efficiency not only as a result of the methodŌĆÖs ingenuity but also at the

expense of extra space.

The two other dictionary

operationsŌĆöinsertion and deletionŌĆöare almost identical to searching. Insertions

are normally done at the end of a list (but see Problem 6 in this sectionŌĆÖs exercises

for a possible modification of this rule). Deletion is performed by searching

for a key to be deleted and then removing it from its list. Hence, the

efficiency of these operations is identical to that of searching, and they are

all (1) in the average case if the number of keys n is about equal to the hash tableŌĆÖs size m.

Closed

Hashing (Open Addressing)

In closed hashing, all keys

are stored in the hash table itself without the use of linked lists. (Of

course, this implies that the table size m must be at least as large as the number of

keys n.) Different strategies can

be employed for collision resolution. The simplest oneŌĆöcalled linear

probingŌĆöchecks the cell following the one where the collision occurs.

If that cell is empty, the new key is installed there; if the next cell is

already occupied, the availability of that cellŌĆÖs immediate successor is

checked, and so on. Note that if the end of the hash table is reached, the

search is wrapped to the beginning of the table; i.e., it is treated as a

circular array. This method is illustrated in Figure 7.6 with the same word

list and hash function used above to illustrate separate chaining.

To search for a given key K, we start by computing h(K) where h is the hash function used in the table construction.

If the cell h(K) is empty, the search is

unsuccessful. If the cell is not empty, we must compare K with the cellŌĆÖs occupant: if they are equal,

we have found a matching key; if they are not, we compare K with a key in the next cell and continue in this

manner until we encounter either a matching key (a successful search) or an

empty cell (unsuccessful search). For example, if we search for the word LIT in the table of Figure 7.6,

we will get h(LIT) = (12 + 9 + 20) mod 13 = 2 and, since cell 2 is empty, we can stop

immediately. However, if we search for KID with h(KID) = (11 + 9 + 4) mod 13 = 11, we will have to compare KID with ARE, SOON, PARTED, and A before we can declare the

search unsuccessful.

Although the search and insertion

operations are straightforward for this version of hashing, deletion is not.

For example, if we simply delete the key ARE from the last state of the

hash table in Figure 7.6, we will be unable to find the key SOON

afterward.

Indeed, after computing h(SOON) = 11, the algorithm would find

this

location empty and report the unsuccessful search result. A simple solution

is to use ŌĆ£lazy deletion,ŌĆØ

i.e., to mark previously occupied locations by a special symbol to distinguish

them from locations that have not been occupied.

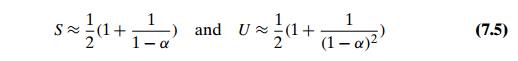

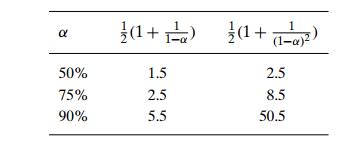

The mathematical analysis of

linear probing is a much more difficult problem than that of separate chaining. The simplified versions of

these results state that the average number of times the algorithm must access

the hash table with the load factor ╬▒ in successful and

unsuccessful searches is, respectively,

(and the accuracy of these

approximations increases with larger sizes of the hash table). These numbers

are surprisingly small even for densely populated tables, i.e., for large

percentage values of ╬▒:

Still, as the hash table gets

closer to being full, the performance of linear prob-ing deteriorates because

of a phenomenon called clustering. A cluster in linear probing is a

sequence of contiguously occupied cells (with a possible wrapping). For

example, the final state of the hash table of Figure 7.6 has two clusters.

Clus-ters are bad news in hashing because they make the dictionary operations

less efficient. As clusters become larger, the probability that a new element

will be attached to a cluster increases; in addition, large clusters increase

the probabil-ity that two clusters will coalesce after a new keyŌĆÖs insertion,

causing even more clustering.

Several other collision

resolution strategies have been suggested to alleviate this problem. One of the

most important is double hashing. Under this scheme, we use another hash

function, s(K), to determine a fixed

increment for the probing sequence to be used after a collision at location l = h(K):

(l + s(K)) mod m, (l + 2s(K))

mod

m, . . . . (7.6)

To guarantee that every

location in the table is probed by sequence (7.6), the incre-ment s(k) and the table size m must be relatively prime, i.e., their only

common divisor must be 1. (This condition is satisfied automatically if m itself is prime.) Some functions recommended

in the literature are s(k) = m ŌłÆ 2 ŌłÆ k mod (m ŌłÆ 2) and s(k) = 8 ŌłÆ (k mod 8) for small tables and s(k) = k mod 97 + 1 for larger ones.

Mathematical analysis of

double hashing has proved to be quite difficult. Some partial results and

considerable practical experience with the method suggest that with good

hashing functionsŌĆöboth primary and secondaryŌĆödouble hashing is su-perior to

linear probing. But its performance also deteriorates when the table gets close

to being full. A natural solution in such a situation is rehashing: the current

table is scanned, and all its keys are relocated into a larger table.

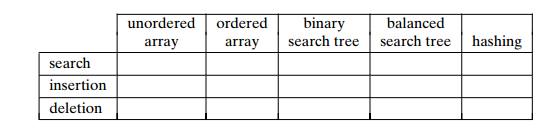

It is worthwhile to compare

the main properties of hashing with balanced search treesŌĆöits principal

competitor for implementing dictionaries.

Asymptotic time efficiency With hashing, searching, insertion, and

deletion can be implemented to take (1) time on the average but (n) time in the very unlikely

worst case. For balanced search trees, the average time efficiencies are (log n) for both the average and worst cases.

Ordering preservation Unlike balanced search trees, hashing does not assume existence of key ordering and usually

does not preserve it. This makes hashing less suitable for applications that

need to iterate over the keys in or-der or require range queries such as

counting the number of keys between some lower and upper bounds.

Since its discovery in the

1950s by IBM researchers, hashing has found many important applications. In

particular, it has become a standard technique for stor-ing a symbol tableŌĆöa

table of a computer programŌĆÖs symbols generated during compilation. Hashing is

quite handy for such AI applications as checking whether positions generated by

a chess-playing computer program have already been con-sidered. With some

modifications, it has also proved to be useful for storing very large

dictionaries on disks; this variation of hashing is called extendible hashing. Since

disk access is expensive compared with probes performed in the main mem-ory, it

is preferable to make many more probes than disk accesses. Accordingly, a

location computed by a hash function in extendible hashing indicates a disk

ad-dress of a bucket that can hold up to b keys. When a keyŌĆÖs bucket is identified, all

its keys are read into main memory and then searched for the key in question.

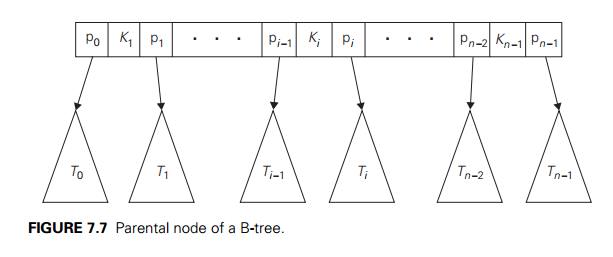

In the next section, we discuss B-trees,

a principal alternative for storing large dictionaries.

Exercises 7.3

For the input 30, 20, 56, 75, 31, 19 and hash function h(K) = K mod 11

construct the open hash table.

find the largest number of key comparisons in a successful search

in this table.

find the average number of key comparisons in a successful search

in this table.

For the input 30, 20, 56, 75, 31, 19 and hash function h(K) = K mod 11

construct the closed hash

table.

find the largest number of key comparisons in a successful search

in this table.

find the average number of key comparisons in a successful search

in this table.

Why is it not a good idea for a hash function to depend on just one

letter (say, the first one) of a natural-language word?

Find the probability of all n keys being hashed to the same cell of a hash

table of size m if the hash function

distributes keys evenly among all the cells of the table.

Birthday paradox The birthday paradox asks how

many people should be in a room so

that the chances are better than even that two of them will have the same

birthday (month and day). Find the quite unexpected answer to this problem.

What implication for hashing does this result have?

Answer the following questions for the separate-chaining version of

hashing.

Where would you insert keys if you knew that all the keys in the

dictionary are distinct? Which dictionary operations, if any, would benefit

from this modification?

We could keep keys of the same linked list sorted. Which of the

dictio-nary operations would benefit from this modification? How could we take

advantage of this if all the keys stored in the entire table need to be sorted?

Explain how to use hashing to check whether all elements of a list

are distinct. What is the time efficiency of this application? Compare its

efficiency with that of the brute-force algorithm (Section 2.3) and of the

presorting-based algorithm (Section 6.1).

Fill in the following table with the average-case (as the first

entry) and worst-case (as the second entry) efficiency classes for the five

implementations of the ADT dictionary:

We have discussed hashing in the context of techniques based on

spaceŌĆōtime trade-offs. But it also takes advantage of another general strategy.

Which one?

Write a computer program that

uses hashing for the following problem. Given a natural-language text, generate

a list of distinct words with the number of occurrences of each word in the

text. Insert appropriate counters in the pro-gram to compare the empirical

efficiency of hashing with the corresponding theoretical results.

Related Topics