Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Principles and Practices of Rehabilitation

Nursing Process: The Patient With Impaired Physical Mobility

NURSING

PROCESS: THE PATIENT WITH IMPAIRED PHYSICAL MOBILITY

Patients who are ill or

injured are frequently placed on bed rest or have their activities limited.

Problems commonly associated with immobility include weakened muscles, joint

contracture, and deformity. Each joint of the body has a normal range of

mo-tion; if the range is limited, the functions of the joint and of the muscles

that move the joint are impaired, and painful deformi-ties may develop. Nurses

must identify patients at risk for such complications.

Another problem

frequently seen in rehabilitation nursing is an altered ambulatory/mobility

pattern. The patient with a dis-ability may be either temporarily or

permanently unable to walk independently and unaided. The nurse assesses the

mobility of the patient and designs care that promotes independent mobility

within the prescribed therapeutic limits.

If a person is not able to exercise and move the joints through their

full range of motion, contractures may develop. A contrac-ture is a shortening

of the muscle and tendon that leads to defor-mity and limits joint mobility.

When the contracted joint is moved, the patient experiences pain; in addition,

more energy is required to move when joints are contracted and deformed.

Assessment

At times, a patient’s mobility is restricted because of pain,

paraly-sis, loss of muscle strength, systemic disease, an immobilizing de-vice

(eg, cast, brace), or prescribed limits to promote healing. Assessment of the

patient’s mobility includes positioning, ability to move, muscle strength and

tone, joint function, and the prescribed mobility limits. The nurse may need to

collaborate with the phys-ical therapist or other team members to assess

mobility.

During position change, transfer, and ambulation activities, the nurse

assesses the patient’s abilities, the extent of disability, and residual

capacity for physiologic adaptation. The nurse ob-serves for orthostatic

hypotension, pallor, diaphoresis, nausea, tachycardia, and fatigue.

If a patient is not able to ambulate without assistance, the nurse

assesses ability to balance, transfer, and use assistive devices (eg, crutches,

walker). Crutch walking requires a high energy expenditure and produces

considerable cardiovascular stress, so older people with reduced exercise

capacity, decreased arm strength, and problems with balance because of old age

and multiple dis-eases may be unable to use them. A walker is more stable and

may be a better choice for such patients. The nurse assesses the pa-tient’s

ability to use various devices that promote mobility. If a patient uses an

orthosis, an external appliance that provides sup-port, prevents or corrects

deformities, and improves function, the nurse monitors the patient for

effective use and potential prob-lems associated with its use.

Nursing Diagnosis

Based on the assessment

data, major nursing diagnoses for the pa-tient may include the following:

· Impaired physical

mobility

· Activity intolerance

· Risk for injury

· Risk for disuse syndrome

· Impaired walking

· Impaired wheelchair

mobility

· Impaired bed mobility

Planning and Goals

The major goals of the

patient may include absence of contrac-ture and deformity, maintenance of

muscle strength and joint mobility, independent mobility, and increased

activity tolerance.

Nursing Interventions

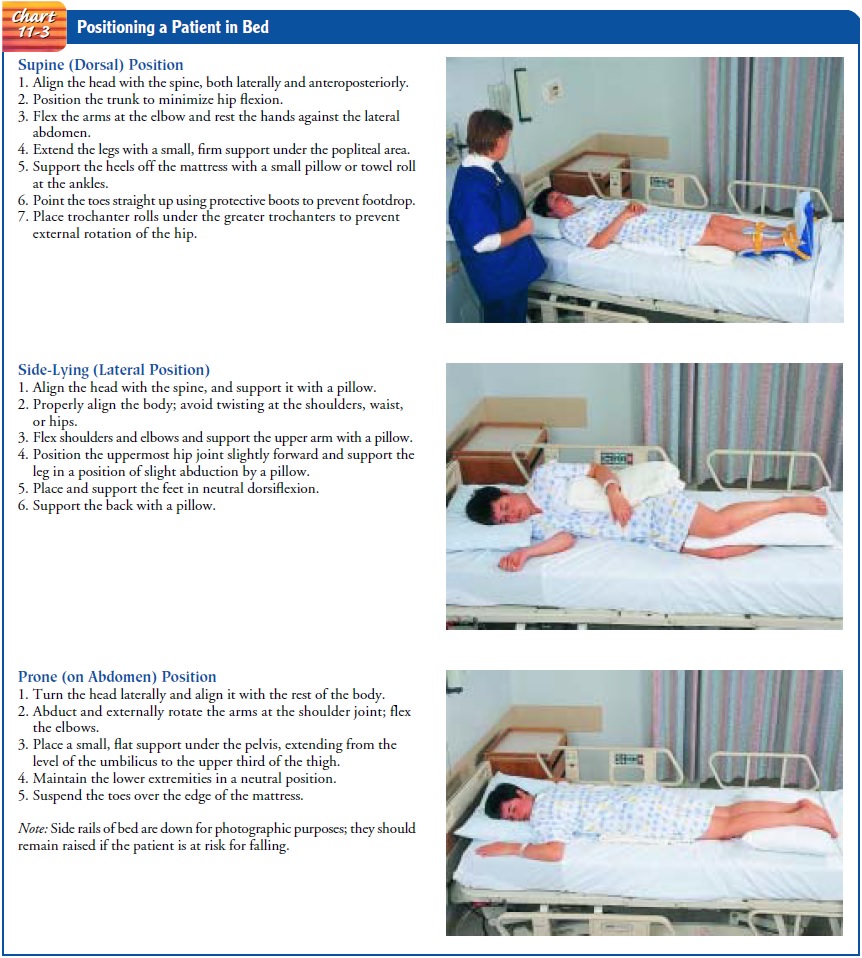

POSITIONING TO PREVENT MUSCULOSKELETAL COMPLICATIONS

Deformities and contractures can often be prevented by proper

positioning. Maintaining correct body alignment when the pa-tient is in bed is

essential regardless of the position selected. Dur-ing each contact with the

patient, the nurse evaluates the patient’s position and assists the patient to

achieve proper positioning and alignment. The most common positions that a

patient assumes in bed are supine (dorsal), side-lying (lateral), and prone.

The nurse helps the patient assume these positions and supports the body in

correct alignment with pillows (Chart 11-3). At times, a splint (eg, wrist or

hand splint) may be fabricated by the occupa-tional therapist to support a

joint and prevent deformity. The nurse must ensure proper use of the splint and

provide skin care.

Preventing External Rotation of the Hip

Patients who are in bed

for any period of time may develop ex-ternal rotation deformity of the hip

because the ball-and-socket joint of the hip has a tendency to rotate outward

when the patient lies on his or her back. A trochanter roll extending from the

crest of the ilium to the midthigh prevents this deformity; with correct

placement, it serves as a mechanical wedge under the projection of the greater

trochanter.

Preventing Footdrop

Footdrop is a deformity in which the foot is plantar flexed (the ankle

bends in the direction of the sole of the foot). If the condi-tion continues

without correction, the patient will not be able to hold the foot in a normal

position and will be able to walk only on his or her toes, without touching the

ground with the heel of the foot. The deformity is caused by contracture of

both the gas-trocnemius and soleus muscles. Damage to the peroneal nerve or

loss of flexibility of the Achilles tendon may result in footdrop.

To prevent this

disabling deformity, the patient is positioned to sit at 90 degrees in a

wheelchair with feet on the footrests or flat on the floor. When the patient is

supine in bed, padded splints or protective boots are used to keep the feet at

right angles to the legs. Frequent skin inspection of the feet must also be

per-formed to determine whether positioning devices have created any unwanted

pressure areas.

The patient is

encouraged to perform the following ankle ex-ercises several times each hour:

dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of the feet, flexion and extension (curl and

stretch) of the toes, and eversion and inversion of the feet at the ankles. The

nurse pro-vides frequent passive range-of-motion exercises if the patient is

unable to perform active exercises.

MAINTAINING MUSCLE STRENGTH AND JOINT MOBILITY

Optimal function depends on the strength of the muscles and joint motion, and active participation in ADLs promotes maintenance of muscle strength and joint mobility. Range-of-motion exercises and specific therapeutic exercises may be included in the nursing plan of care.

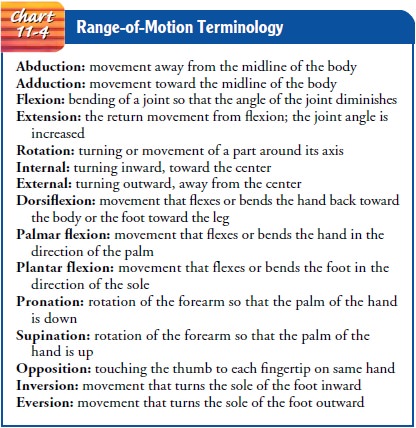

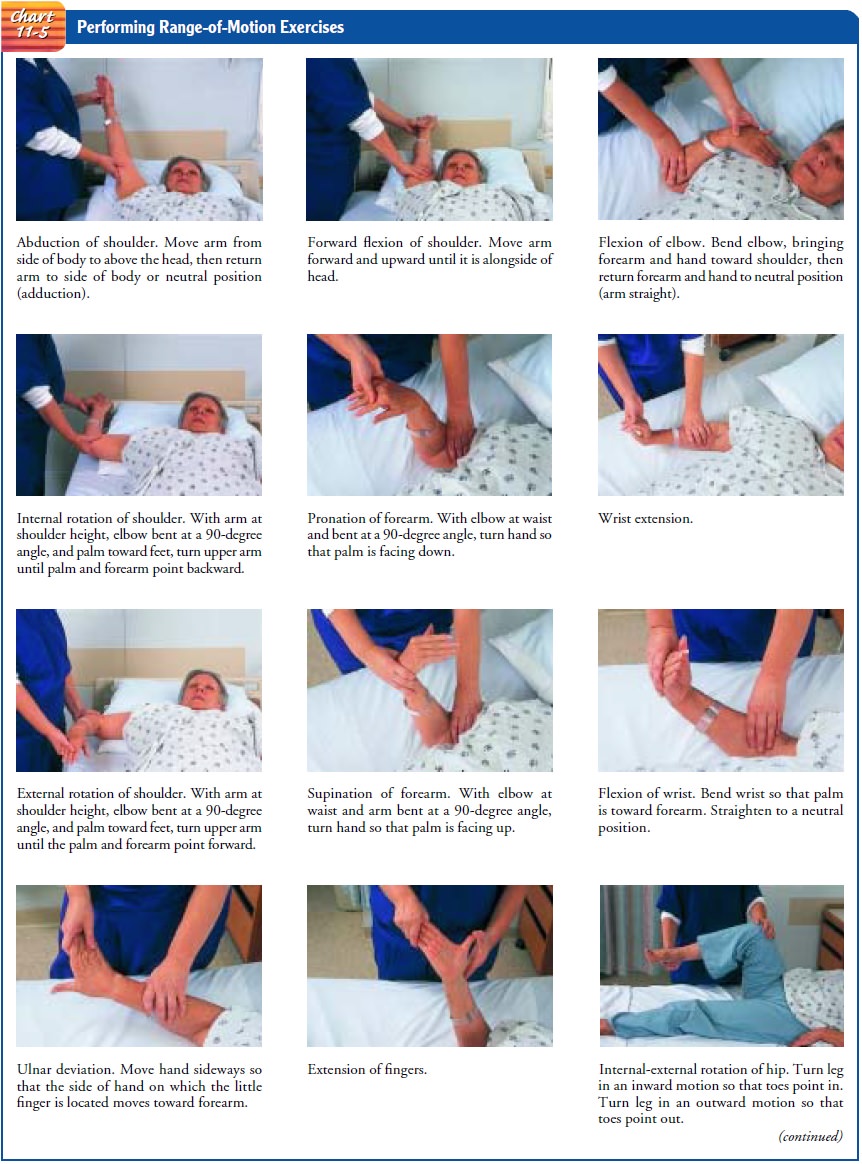

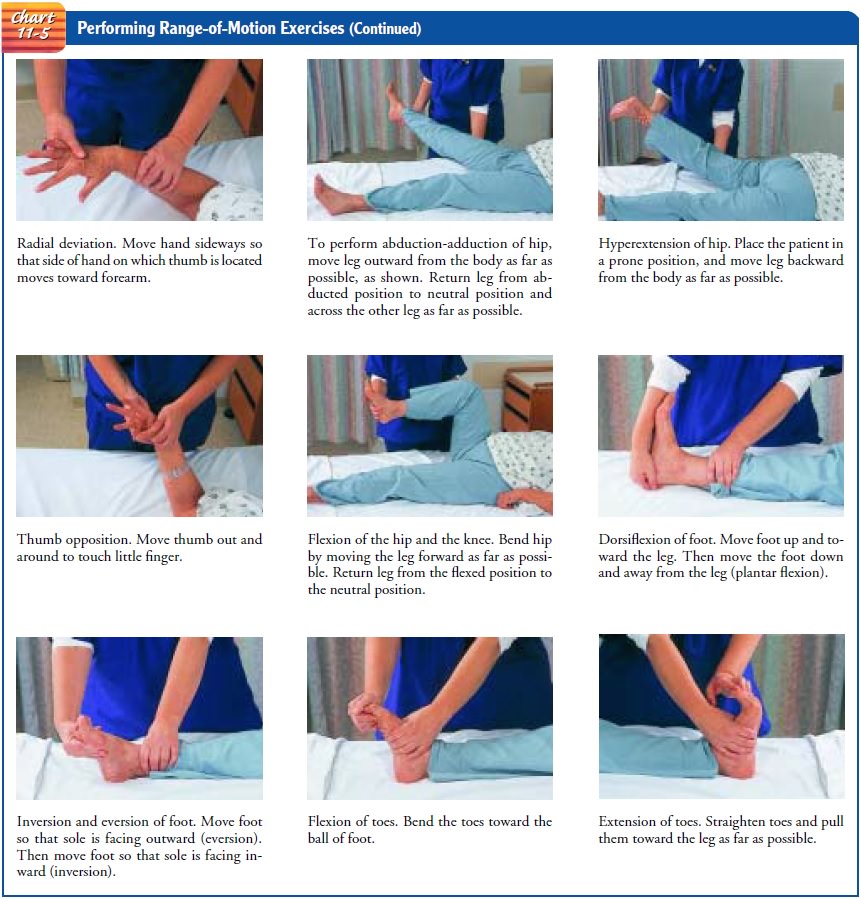

Performing Range-of-Motion Exercises

Range of motion is

movement of a joint through its full range in all appropriate planes (Chart

11-4). To maintain or increase the motion of a joint, range-of-motion exercises

are initiated as soon as the patient’s condition permits. The exercises are

planned forthe individual to accommodate the wide variation in the degrees of

motion that people of varying body builds and age groups can attain (Chart

11-5).

Range-of-motion exercises may be active (performed by the patient under supervision of the nurse), assisted (with the nurse helping if the patient is unable to do the exercise independently), or passive (performed by the nurse). Unless prescribed otherwise, a joint should be moved through its range of motion three times, at least twice a day. The joint to be exercised is supported, the bones above the joint are stabilized, and the body part distal to the joint is moved through the range of motion of the joint. For example, the humerus must be stabilized while the radius and ulna are moved through their range of motion at the elbow joint.

The joint should not be

moved beyond its free range of mo-tion; the joint is moved to the point of

resistance and stopped at the point of pain. If muscle spasms are present, the

joint is moved slowly to the point of resistance. Gentle, steady pressure is

then applied until the muscle relaxes, and the motion is continued to the

joint’s final point of resistance.

To perform assisted or

passive range-of-motion exercises, the patient must be in a comfortable supine

position with arms at the sides and knees extended. Good body posture is

maintained during the exercises. The nurse also uses good body mechanics during

the exercise session.

Performing Therapeutic Exercises

Therapeutic exercises

are prescribed by the physician and per-formed with the assistance and guidance

of a physical therapist or nurse. Research is also underway to develop

computerized robots with gentle, compliant behavior that could be used in the

home setting for upper-extremity exercises (Krebs, 2000).

The patient should have

a clear understanding of the goal of the prescribed exercise. Written

instructions about the frequency, duration, and number of repetitions, as well

as simple line draw-ings of the exercise, help to ensure adherence to the

exercise program.

Exercise, when performed correctly, assists in maintaining and building

muscle strength, maintaining joint function, preventing deformity, stimulating

circulation, developing endurance, and promoting relaxation. Exercise is also

valuable in helping to re-store motivation and the well-being of the patient.

Weight-bearing exercises may slow the bone loss that occurs with disability.

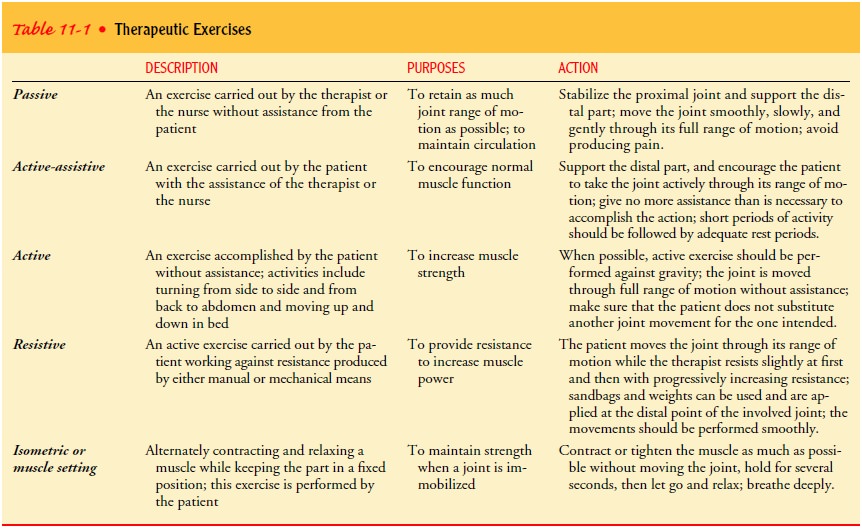

There are five types of exercise: passive, active-assistive, active, resistive,

and isometric. The description, purpose, and action of each of these exercises

are summarized in Table 11-1.

PROMOTING INDEPENDENT MOBILITY

When the patient’s condition stabilizes and the physical condition

permits, the patient is assisted to sit up on the side of the bed and then to

stand. The patient’s tolerance of this activity is assessed. Orthostatic

(postural) hypotension may develop when the patient assumes a vertical

position. Because of inadequate vasomotor re-flexes, blood pools in the

splanchnic (visceral) area and in the legs, resulting in inadequate cerebral

circulation. If indicators of orthostatic hypotension (eg, drop in blood

pressure, pallor, di-aphoresis, nausea, tachycardia, dizziness) are present,

the activity is stopped, and the patient is assisted to a supine position in

bed.

Some disabilities, such

as spinal cord injury, acute brain injury, and other conditions that require

extended periods in the recum-bent position, prevent patients from assuming an

upright position at the bedside. Several strategies can be used to assist a

patient to assume a 90-degree sitting position. First, a reclining wheelchair

with elevating leg rests allows a slow and controlled progression from a supine

position to a 90-degree sitting position. A tilt table, a board that can be

tilted in 5- to 10-degree increments from a horizontal to a vertical position,

may also be used. The tilt table promotes vasomotor adjustment to positional

changes and helps the patient with limited standing balance and limited

weight-bearing activities to avoid the decalcification of bones and low bone

mass associated with disuse syndrome and lack of weight-bearing exercise.

Elastic compression stockings are used to prevent venous sta-sis. For

some patients, a compression garment (leotard) or snug-fitting abdominal binder

and elastic compression bandaging of the legs are needed to prevent venous

stasis and ensuing orthostatic hypotension. When the patient is standing, the

feet are protected with a pair of properly fitted shoes. Extended periods of

standing are avoided because of venous pooling and pressure on the soles of the

feet. The nurse monitors the patient’s blood pressure and pulse and observes

for signs of orthostatic hypotension and cerebral in-sufficiency (eg, the

patient reports feeling faint and weak), which suggest intolerance of the

upright position. If the patient does not tolerate the upright position, the

nurse should recline the patient and elevate the patient’s legs.

Assisting the Patient With Transfer

A transfer is movement

of the patient from one place to another (eg, bed to chair, chair to commode,

wheelchair to tub). As soon as the patient is permitted out of bed, transfer

activities are started. The nurse assesses the patient’s ability to participate

ac-tively in the transfer and determines in conjunction with an oc-cupational

therapist or physical therapist the required adaptive equipment to promote

independence and safety. A lightweight wheelchair with brake extensions,

removable and detachable arm rests, and leg rests minimizes structural

obstacles during the trans-fer. Tub seats or benches make transfers in and out

of tubs easier and safer. Raised, padded commode seats may also be warranted for

patients who must avoid flexing the hips greater than 90 de-grees when

transferring to a toilet.

It is important that the patient maintain muscle strength and, if possible, perform push-up exercises to strengthen the arm and shoulder extensor muscles. The push-up exercise requires the patient to sit upright in bed; a book is placed under each of the patient’s hands to provide a hard surface, and the patient is in-structed to push down on the book raising, the body. The nurse should encourage the patient to raise and move the body in dif-ferent directions by means of these push-up exercises.

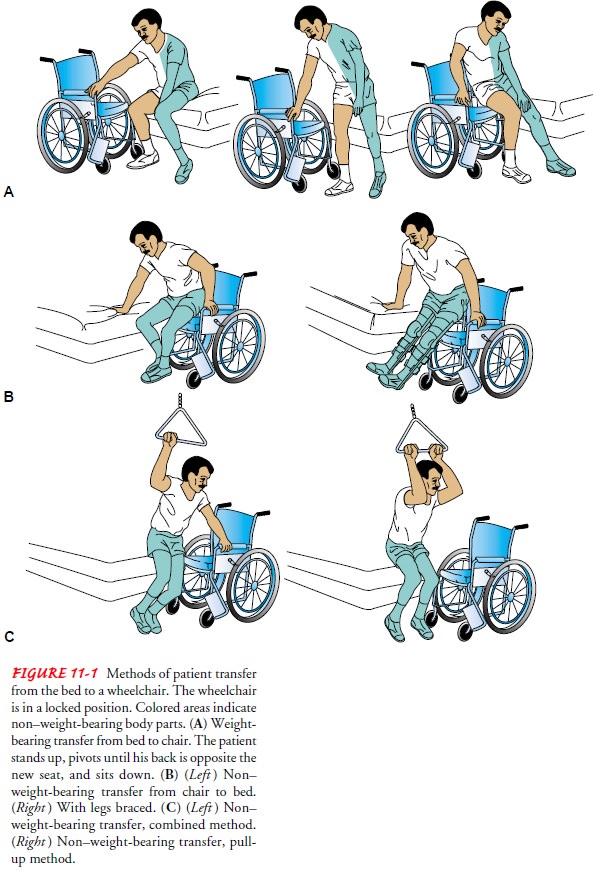

The nurse or physical therapist teaches the patient how to trans-fer. There are several methods of transferring from the bed to the wheelchair when the patient is unable to stand, and the technique chosen

should be appropriate for the patient, considering his or her abilities and

disabilities. It is helpful for the nurse to demonstrate the technique. If the

physical therapist is involved in teaching the patient to transfer, the nurse

and the physical therapist must col-laborate so that consistent instructions

are given to the patient. Dur-ing transfer, the nurse assists and coaches the

patient. Figure 11-1 shows weight-bearing and non–weight-bearing transfer.

If the patient’s muscles are not strong enough to overcome the

resistance of body weight, a polished lightweight board (transfer board,

sliding board) may be used to bridge the gap between the bed and the chair. The

patient slides across on the board with or without assistance from a caregiver.

This board may also be used to transfer the patient from the chair to the

toilet or bathtub bench. The nurse should make sure that the patient’s fingers

do not curl around the edge of the board during the transfer, because the

weight of the patient’s body can crush them as the patient moves across the

board. Safety is a primary concern during a transfer:

•

Wheelchairs and beds must be locked before the

patient transfers.

•

Detachable arm and foot rests are removed to make

getting in and out of the chair easier.

•

One end of the transfer board is placed under the

patient’s buttocks and the other end on the surface to which the transfer is

being made (eg, the chair).

•

The patient is instructed to lean forward, push up

with his or her hands, and then slide across the board to the other surface.

•

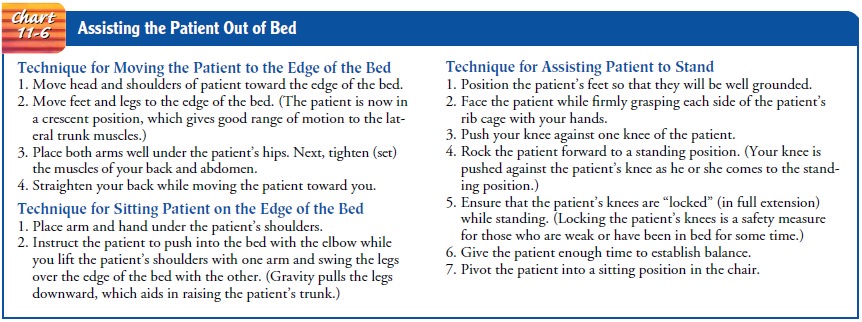

The nurse frequently assists weak and incapacitated

patients out of bed. The nurse supports and gently assists the patient dur-ing

position changes, protecting the patient from injury. The nurse avoids pulling

on the weak or paralyzed upper extremity, to prevent dislocation of the

shoulder. The patient is assisted to move toward the stronger side (Chart 11-6).

In the home setting, getting in and out of bed and perform-ing chair,

toilet, and tub transfers are difficult for patients with weak musculature and

loss of hip, knee, and ankle motion. A rope attached to the headboard of the

bed enables the patient to pull toward the center of the bed, and the use of a

rope attached to the footboard facilitates getting in and out of bed. The

height of a chair can be raised with cushions on the seat or with hollowed-out

blocks placed under the chair legs. Grab bars can be attached to the wall near

the toilet and tub to provide leverage and stability.

Preparing for Ambulation

Regaining the ability to

walk is a prime morale builder. However, to be prepared for ambulation—whether

with brace, walker, cane, or crutches—the patient must strengthen the muscles

required. Exercise, therefore, is the foundation of preparation. The nurse and

physical therapist instruct and supervise the patient in these exercises.

For ambulation, the quadriceps muscles, which stabilize the knee joint,

and the gluteal muscles are strengthened. To perform quadriceps-setting

exercises, the patient contracts the quadriceps muscle by attempting to push

the popliteal area against the mat-tress and at the same time raising the heel.

The patient maintains the muscle contraction until a count of five and relaxes

for a count of five. The exercise is repeated 10 to 15 times hourly. Exercising

the quadriceps muscles prevents flexion contractures of the knee.

In gluteal setting, the patient contracts or “pinches” the but-tocks

together to the count of five, relaxes for the count of five, and repeats 10 to

15 times hourly. If ambulatory aids (ie, walker, cane, crutches) are to be

used, the muscles of the upper extremities are exercised and strengthened.

Push-up exercises are useful. While in a sitting position, the patient raises

the body by pushing the hands against the chair seat or mattress. The patient

should be encour-aged to do push-up exercises while in a prone position also.

Pull-up exercises done on a trapeze while lifting the body are also effective

for conditioning. The patient is taught to raise the arms above the head and

then lower them in a slow, rhythmic manner while hold-ing weights. Gradually,

the weight is increased. The hands are strengthened by squeezing a rubber ball.

Typically, the physical

therapist designs exercises to help the patient develop the sitting and

standing balance, stability, and co-ordination needed for ambulation. After

sitting and standing bal-ance are achieved, the patient uses parallel bars.

Under the supervision of the physical therapist, the patient practices

shift-ing weight from side to side, lifting one leg while supporting weight on

the other, and then walking between the parallel bars.

A patient who is ready to begin ambulation must be fitted with the appropriate ambulatory aid, instructed about the prescribed weight-bearing limits (eg, non–weight-bearing, partial weight-bearing ambulation), and taught how to use the aid safely. The nurse continually assesses the patient for stability and adherence to weight-bearing precautions and protects the patient from falling. The nurse provides contact guarding by holding on to a gait belt that the patient wears around the waist. The patient should wear sturdy, well-fitting shoes and be advised of the dangers of wet or highly polished floors and throw rugs. The patient should also learn how to ambulate on inclines, uneven surfaces, and stairs.

Ambulating With Crutches

Patients who are prescribed partial weight-bearing or non–

weight-bearing ambulation may use crutches. The nurse or physi-cal therapist

should determine whether crutches are appropriate for the patient, because good

balance, adequate cardiovascular reserve, strong upper extremities, and erect

posture are essential for crutch walking. Ambulating a functional distance (at

least the length of a room or house) or maneuvering stairs on crutches requires

signifi-cant arm strength, because the arms must bear the patient’s weight.

Muscle groups important for crutch walking include the following:

• Shoulder depressors—to

stabilize the upper extremity and prevent shoulder hiking

• Shoulder adductors—to hold

the crutch top against the chest wall

• Arm flexors, extensors, and

abductors (at the shoulder)—to move crutches forward, backward, and sideways

• Forearm extensors—to prevent

flexion or buckling; impor-tant in raising the body for swinging gait

• Wrist extensors—to enable

weight bearing on hand pieces

• Finger and thumb flexors—to

grasp the hand piece

Preparing the Patient to Walk With Crutches

Preparatory exercises are prescribed to strengthen the shoulder gir-dle

and upper extremity muscles. Meanwhile, crutches need to be adjusted to the

patient before the patient begins ambulating. To determine the approximate

crutch length, the patient may be mea-sured standing or lying down. A standing

patient is positioned against the wall with the feet slightly apart and away

from the wall. Then a distance of 5 cm (2 inches) is marked on the floor, out

to the side from the tip of the toe; 15 cm (6 inches) is measured straight

ahead from the first mark, and this point is marked on the floor. Next, 5 cm (2

inches) is measured below the axilla to the sec-ond mark for the approximate

crutch length.

If the patient has to be

measured while lying down, he or she is measured from the anterior fold of the

axilla to the sole of the foot, and then 5 cm (2 inches) is added. If the

patient’s height is used, 40 cm (16 inches) is subtracted to obtain the

approximate crutch length. The hand piece should be adjusted to allow 20 to 30

degrees of flexion at the elbow. The wrist should be extended and the hand

dorsiflexed. A foam rubber pad on the underarm piece is used to relieve

pressure of the crutch on the upper arm and thoracic cage. For safety, crutches

should have large rubber tips, and the patient should wear firm-soled shoes

that fit well.

Teaching Crutch Walking

The nurse or physical

therapist explains and demonstrates to the patient how to use the crutches. The

patient learns standing bal-ance by standing on the unaffected leg by a chair.

To help the pa-tient maintain balance, the nurse holds the patient near the

waist or uses a transfer belt.

The patient is taught to

support his or her weight on the hand pieces. (For patients who are unable to

support their weight through the wrist and hand because of arthritis or

fracture, plat-form crutches that support the forearm and allow the weight to

be borne through the elbow are available.) If weight is borne on the axilla,

the pressure of the crutch can damage the brachial plexus nerves, producing

“crutch paralysis.”

For maximum stability,

the patient first assumes the tripod po-sition by placing the crutches about 20

to 25 cm (8 to 10 inches) in front and to the side of his or her toes (Fig.

11-2). (This base of support is adjusted according to the height of the

patient; a tall person requires a broader base of support than does a short

per-son). In this position, the patient learns how to shift weight and maintain

balance.

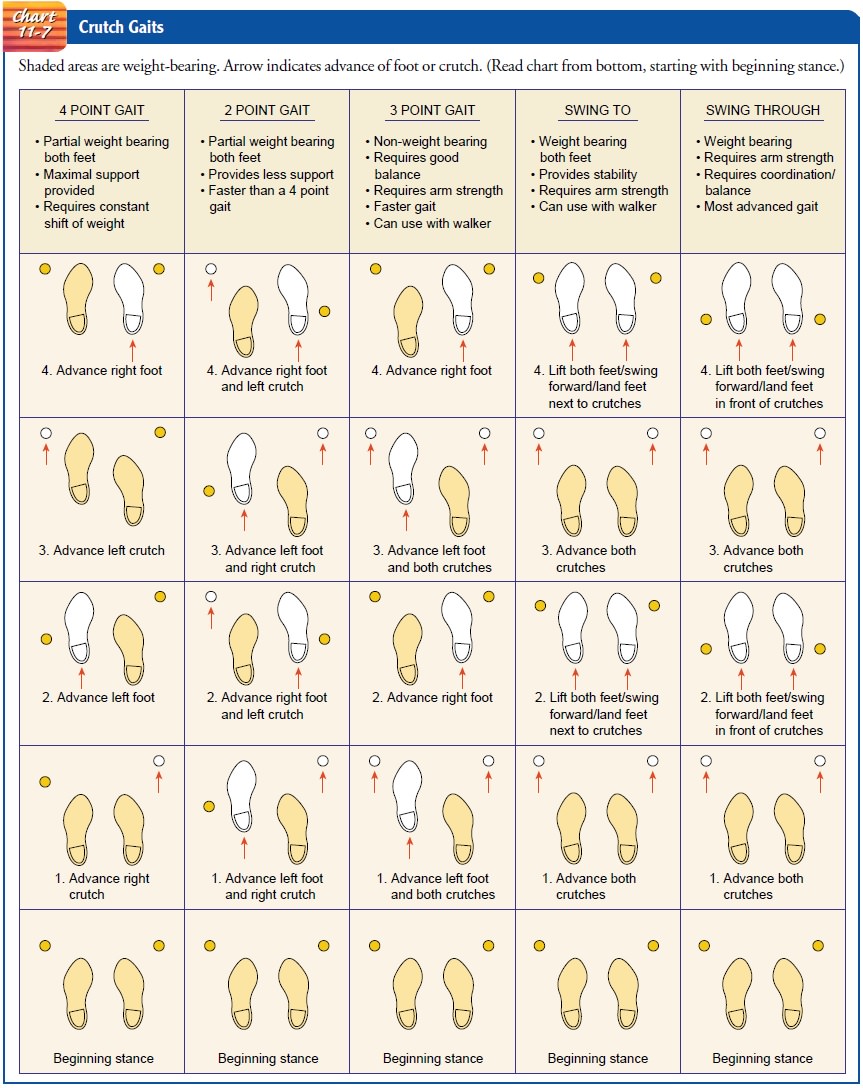

Before teaching crutch walking, the nurse or therapist deter-mines which gait will be best for the patient. The selection of the crutch gait depends on the type and severity of the disability and on the patient’s physical condition, arm and trunk strength, and body balance. The patient should be taught two gaits so that he or she can change from one to another. Shifting crutch gaits re-lieves fatigue, because each gait requires the use of a different combination of muscles (if a muscle is forced to contract steadily without relaxing, the circulation of the blood to that part is de-creased). A faster gait can be used when walking an uninterrupted distance, and a slower gait can be used for short distances or in crowded places. The more common gaits are the four-point, the three-point, the two-point, and the swinging-to and swinging through gaits. The sequence of movements for each of these gaits is depicted in Chart 11-7.

The nurse walks with the

patient who is just learning how to ambulate with crutches, holding him or her

at the waist as needed for balance. During this time, the nurse protects the

patient from falls and continually assesses the patient’s stability and

stamina, since prolonged periods of bed rest and inactivity affect a patient’s

strength and endurance. Sweating and shortness of breath are in-dications that

crutch-walking practice should be stopped and the patient permitted to rest.

Teaching Maneuvering Techniques

Before a patient is considered to be independent in crutch walk-ing, he

or she needs to learn to sit in a chair, stand from sitting, and go up and down

stairs.

To sit down:

1.

Grasp the crutches at the hand pieces for control.

2.

Bend forward slightly while assuming a sitting

position.

3. Place the affected leg

forward to prevent weight-bearing and flexion.

To stand up:

1.

Move forward to the edge of the chair with the

strong leg slightly under the seat.

2.

Place both crutches in the hand on the side of the

affected extremity.

3.

Push down on the hand piece while raising the body

to a standing position.

To go down stairs:

1.

Walk forward as far as possible on the step.

2. Advance crutches to the lower step. The weaker leg is ad-vanced first and then the stronger one. In this way, the stronger extremity shares with the arms the work of raising and lowering the body weight.

To go up stairs:

·

Advance the stronger leg first up to the next step.

·

Advance the crutches and the weaker extremity. Note

that the strong leg goes up first and comes down last. A mem-ory device for the

patients is, “Up with the good, down with the bad.”

AMBULATING WITH A WALKER

A walker provides more support and stability than a cane or crutches.

There are two types of walkers: pick-up walkers and rolling walkers. A pick-up

walker (one that has to be picked up and moved with each step forward) does not

permit a natural walking pattern and is useful for patients who have poor

balance or limited cardiovascular reserve or who cannot use crutches. A rolling

walker allows automatic walking and is used by patients who cannot lift or who

inappropriately carry a pick-up walker. The height of the walker is adjusted to

the patient. The patient’s arms resting on the walker hand grips should exhibit

20 to 30 degrees of flexion at the elbows. The patient should wear sturdy,

well-fitting shoes. The nurse walks with the patient, holds him or her at the

waist as needed for balance, continually assesses the patient’s stability, and

protects the patient from falls.

The patient is

instructed to ambulate with a pick-up walker as follows:

·

Push off a chair or bed to come to a standing

position. Never pull yourself up using the walker.

·

Hold the walker on the hand grips for stability.

·

Lift the walker, placing it in front of you while

leaning your body slightly forward.

·

Walk into the walker, supporting your body weight

on your hands when advancing your weaker leg, permitting partial weight bearing

or non–weight bearing as prescribed.

· Balance yourself on your

feet.

·

Lift the walker, and place it in front of you

again. Continue this pattern of walking.

·

Remember to look up as you walk.

USING A CANE

A cane helps the patient

walk with greater balance and support and relieves the pressure on

weight-bearing joints by redistribut-ing weight. Quad canes (four-footed canes)

provide more stabil-ity than straight canes. To fit the patient for a cane, the

patient is instructed to flex the elbow at a 30-degree angle, hold the handle

of the cane about level with the greater trochanter, and place the tip of the

cane 15 cm (6 inches) lateral to the base of the fifth toe. Adjustable canes

make individualization easy. The cane should be fitted with a gently flaring

tip that has flexible, concentric rings; the tip with its concentric rings

provides optimal stability, functions as a shock absorber, and enables the

patient to walk with greater speed and less fatigue.

The cane is held in the hand opposite the affected extremity. In normal

walking, the opposite leg and arm move together (recipro-cal motion); this

motion is to be carried through in walking with a cane. The patient is taught

to ambulate with a cane as follows:

Cane–foot sequence:

1.

Hold the cane in the hand opposite the affected

extremity to widen the base of support and to reduce the stress on the involved

extremity. If the patient for some reason is unable to use the cane in the

opposite hand, the cane may be used on the same side.

2.

Advance the cane at the same time the affected leg

is moved forward.

3.

Keep the cane fairly close to the body to prevent

leaning.

4. Bear down on the cane

when the unaffected extremity be-gins the swing phase.

To go up and down stairs

using the cane:

1.

Step up on the unaffected extremity.

2.

Place the cane and affected extremity up on the

step.

3.

Reverse this procedure for descending steps (“up

with the good, down with the bad”).

As for all patients

beginning ambulation with an ambulatory aid, the nurse continually assesses the

patient’s stability and pro-tects the patient from falls. The nurse accompanies

the patient, holding him or her at the waist as needed for balance. The patient

is assessed for tolerance of walking, and rest periods are provided as needed.

ASSISTING THE PATIENT WHO USES AN ORTHOSIS OR PROSTHESIS

Orthoses and prostheses are designed to facilitate mobilization and to

maximize the patient’s quality of life. An orthosis is an external appliance

that provides support, prevents or corrects deformities, and improves function.

Orthoses include braces, splints, collars, corsets, or supports that are designed

and fitted by an orthotist or prosthetist. Static orthoses (no moving parts)

are used to stabilize joints and prevent contractures. Dynamic or-thoses are

flexible and are used to improve function by assisting weak muscles. A

prosthesis is an artificial body part; it may be in-ternal, such as an

artificial knee or hip joint, or external, such as an artificial leg or arm.

In addition to learning

how to apply and remove the orthosis and maneuver the affected body part

correctly, rehabilitation pa-tients must learn how to properly care for the

skin that comes in contact with the appliance. Skin problems or pressure ulcers may develop if the

device is applied too tightly or too loosely, or if it is adjusted improperly.

The nurse instructs the patient to clean and inspect the skin daily, to make

sure the brace fits snugly without being too tight, to check that the padding

distributes pressure evenly, and to wear a cotton garment without seams

be-tween the orthosis and the skin.

If the patient has had an amputation, the nurse promotes tissue healing,

uses compression dressings to promote residual limb shaping, and minimizes

contracture formation. A permanent prosthetic limb cannot be fitted until the

tissue has healed com-pletely and the residual limb shape is stable and free of

edema. The nurse also helps the patient cope with the emotional issues

sur-rounding loss of a limb and encourages acceptance of the pros-thesis. The

prosthetist, the nurse, and the physician collaborate to provide instructions

related to skin care and care of the prosthesis.

Evaluation

EXPECTED PATIENT OUTCOMES

Expected patient

outcomes may include:

1.

Demonstrates improved physical mobility

a.

Maintains muscle strength and joint mobility

b.

Does not develop contractures

c.

Participates in exercise program

2.

Transfers safely

a.

Demonstrates assisted transfers

Performs independent

transfers

3.

Ambulates with maximum independence

a.

Uses ambulatory aid safely

b.

Adheres to weight-bearing prescription

c.

Requests assistance as needed

4.

Demonstrates increased activity tolerance

a.

Does not experience episodes of orthostatic

hypotension

b. Reports absence of

fatigue with ambulatory efforts

c.

Gradually increases distance and speed of

ambulation

Related Topics