Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Postoperative Nursing Management

Nursing Management in the PACU

NURSING MANAGEMENT IN THE PACU

The

nursing management objectives for the patient in the PACU are to provide care

until the patient has recovered from the effects of anesthesia (eg, until

resumption of motor and sensory functions), is oriented, has stable vital

signs, and shows no evidence of hem-orrhage or other complications.

Assessing the Patient

Frequent,

skilled assessments of the blood oxygen saturation level, pulse rate and

regularity, depth and nature of respirations, skin color, level of

consciousness, and ability to respond to com-mands are the cornerstones of

nursing care in the PACU. The nurse performs a baseline assessment, then checks

the surgical site for drainage or hemorrhage and makes sure that all drainage

tubes and monitoring lines are connected and functioning.

After

the initial assessment, vital signs are monitored and the patient’s general

physical status is assessed at least every 15 minutes. Patency of the airway

and respiratory function are always evalu-ated first, followed by assessment of

cardiovascular function, the condition of the surgical site, and function of

the central nervous system. The nurse needs to be aware of any pertinent

informa-tion from the patient’s history that may be significant (eg, patient is

hard of hearing, has a history of seizures, has diabetes, or is allergic to

certain medications or to latex).

Maintaining a Patent Airway

The

primary objective in the immediate postoperative period is to maintain

pulmonary ventilation and thus prevent hypoxemia (reduced oxygen in the blood)

and hypercapnia (excess carbon dioxide in the blood). Both can occur if the

airway is obstructed and ventilation is reduced (hypoventilation). Besides

checking the physician’s orders for and administering supplemental oxy-gen, the

nurse assesses respiratory rate and depth, ease of respira-tions, oxygen

saturation, and breath sounds (Litwack, 1999; Meeker & Rothrock, 1999).

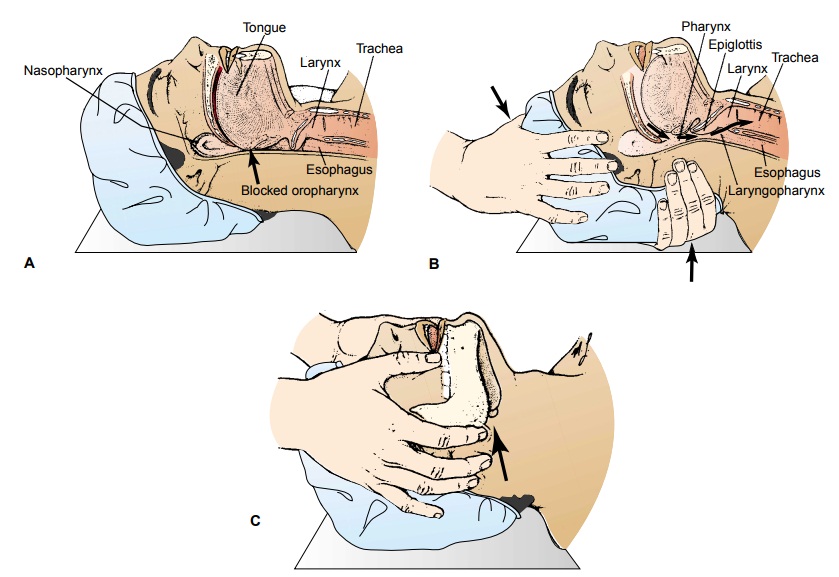

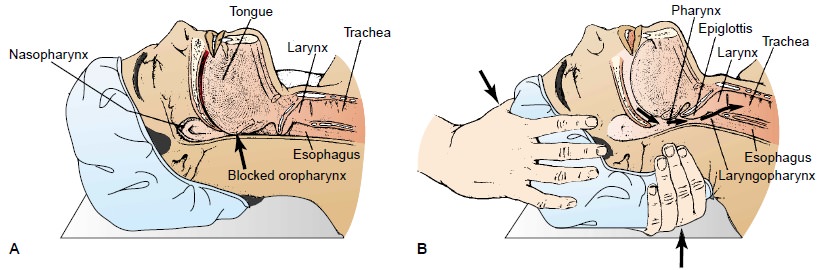

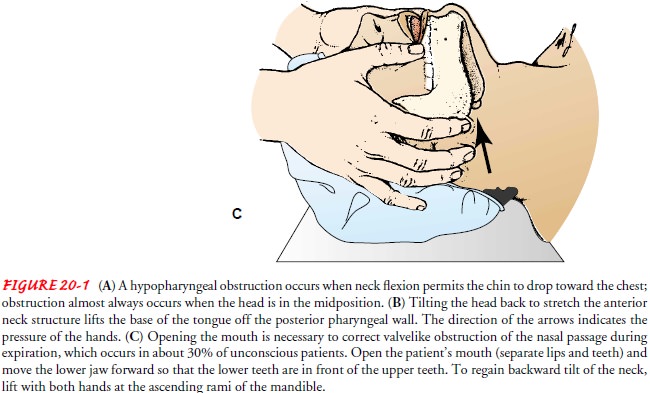

Patients

who have experienced prolonged anesthesia usually are unconscious, with all

muscles relaxed. This relaxation extends to the muscles of the pharynx. When

the patient lies on his or her back, the lower jaw and the tongue fall backward

and the air pas-sages become obstructed (Fig. 20-1A). This is called hypopha-ryngeal obstruction. Signs of occlusion

include choking, noisy and irregular respirations, decreased oxygen saturation

scores, and within minutes a blue, dusky color (cyanosis) of the skin. Because

movement of the thorax and the diaphragm does not necessarily indicate that the

patient is breathing, the nurse needs to place the palm of the hand at the

patient’s nose and mouth to feel the ex-haled breath.

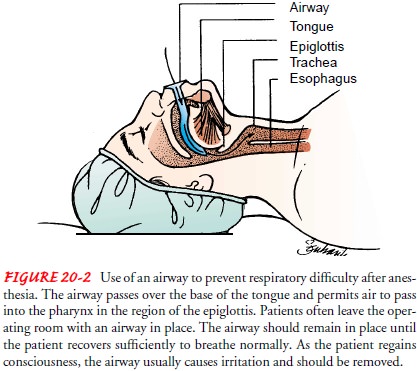

The

anesthesiologist or anesthetist may leave a hard rubber or plastic airway in

the patient’s mouth (Fig. 20-2) to maintain a patent airway. Such a device

should not be removed until signs such as gagging indicate that reflex action

is returning. Alterna-tively, the patient may enter the PACU with an

endotracheal tube still in place and may require continued mechanical

ventilation. The nurse assists in initiating the use of the ventilator and in

the weaning and extubation processes. Some patients, particularly those who

have had extensive or lengthy surgical procedures, may be transferred from the

operating room directly to the intensive care unit or may be transferred from

the PACU to the intensive care unit while still intubated and on mechanical

ventilation.

Respiratory

difficulty can also result from excessive secretion of mucus or aspiration of

vomitus. Turning the patient to one side allows the collected fluid to escape

from the side of the mouth. If the teeth are clenched, the mouth may be opened

man-ually but cautiously with a padded tongue depressor. The head of the bed is

elevated 15 to 30 degrees unless contraindicated, and the patient is closely

observed to maintain the airway as well as to minimize the risk of aspiration.

If vomiting occurs, the patient is turned to the side to prevent aspiration and

the vomitus is col-lected in the emesis basin. Mucus or vomitus obstructing the

pharynx or the trachea is suctioned with a pharyngeal suction tip or a nasal

catheter introduced into the nasopharynx or orophar-ynx. The catheter can be

passed into the nasopharynx or orophar-ynx safely to a distance of 15 to 20 cm

(6 to 8 inches). Caution is necessary in suctioning the throat of a patient who

has had a ton-sillectomy or other oral or laryngeal surgery because of risk for

bleeding and discomfort.

Maintaining Cardiovascular Stability

To

monitor cardiovascular stability, the nurse assesses the pa-tient’s mental

status; vital signs; cardiac rhythm; skin tempera-ture, color, and moisture;

and urine output. Central venous pressure, pulmonary artery pressure, and

arterial lines are moni-tored if the patient’s condition requires such

assessment. The nurse also assesses the patency of all IV lines. The primary

cardio-vascular complications seen in the PACU include hypotension and shock,

hemorrhage, hypertension, and dysrhythmias.

HYPOTENSION AND SHOCK

Hypotension

can result from blood loss, hypoventilation, posi-tion changes, pooling of

blood in the extremities, or side effects of medications and anesthetics; the

most common cause is loss of circulating volume through blood and plasma loss.

If the amount of blood loss exceeds 500 mL (especially if the loss is rapid),

re-placement is usually indicated.

Shock, one of the most serious postoperative complications, can result from hypovolemia. Shock may be described as inadequate cellular oxygenation accompanied by the inability to excrete waste products of metabolism. Hypovolemic shock is characterized by a fall in venous pressure, a rise in peripheral resistance, and tachy-cardia. Neurogenic shock, a less common cause of shock in the sur-gical patient, occurs as a result of decreased arterial resistance caused by spinal anesthesia. It is characterized by a fall in blood pressure due to pooling of blood in dilated capacitance vessels (those with the ability to change volume capacity). Cardiogenic shock is unlikely in the surgical patient except if the patient has se-vere preexisting cardiac disease or experienced a myocardial in-farction during surgery.

The classic signs of shock are:

• Pallor

• Cool, moist skin

• Rapid breathing

• Cyanosis of the lips, gums, and tongue

• Rapid, weak, thready pulse

• Decreasing pulse pressure

• Low blood pressure and concentrated urine

Hypovolemic

shock can be avoided largely by the timely ad-ministration of IV fluids, blood,

blood products, and medica-tions that elevate blood pressure. Other factors may

contribute to hemodynamic instability, and the PACU nurse implements mul-tiple

measures to manage these factors. Pain is controlled by mak-ing the patient as

comfortable as possible and by using opioids judiciously. Exposure is avoided,

and normothermia is main-tained to prevent vasodilation.

Volume

replacement is the primary intervention for shock. An infusion of lactated

Ringer’s solution or blood component ther-apy is initiated. Oxygen is administered

by nasal cannula, face-mask, or mechanical ventilation. Cardiotonic,

vasodilator, and corticosteroid medications may be prescribed to improve

cardiac function and reduce peripheral vascular resistance. The patient is kept

warm while avoiding overheating to prevent cutaneous ves-sels from dilating and

depriving vital organs of blood. The patient is placed flat in bed with the

legs elevated. Respiratory and pulse rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen

concentration, urinary output, level of consciousness, central venous pressure,

pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and cardiac

output are monitored to provide information on the patient’s respiratory and

cardiovascular status. Vital signs are monitored continuously until the patient’s

condition has stabilized.

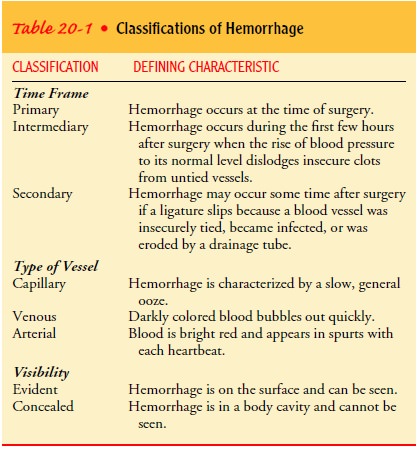

HEMORRHAGE

Hemorrhage

is an uncommon yet serious complication of surgery that can result in death

(Finkelmeier, 2000). It can present in-sidiously or emergently at any time in

the immediate postopera-tive period or up to several days after surgery (Table

20-1). When blood loss is extreme, the patient is apprehensive, restless, and

thirsty; the skin is cold, moist, and pale. The pulse rate increases, the

temperature falls, and respirations are rapid and deep, often of the gasping

type spoken of as “air hunger.” If hemorrhage pro-gresses untreated, cardiac

output decreases, arterial and venous blood pressure and hemoglobin level fall

rapidly, the lips and the conjunctivae become pallid, spots appear before the

eyes, a ring-ing is heard in the ears, and the patient grows weaker but remains

conscious until near death.

Transfusing

blood or blood products and determining the cause of hemorrhage are the initial

therapeutic measures. The sur-gical site and incision should always be inspected

for bleeding. If bleeding is evident, a sterile gauze pad and a pressure

dressing are applied, and the site of the bleeding is elevated to heart level

if possible. The patient is placed in the shock position (flat on back; legs

elevated at a 20-degree angle; knees kept straight). If the source of bleeding

is concealed, the patient may be taken back to the operating room for emergency

exploration of the surgical site.

Special

considerations must be given to patients who decline blood transfusions, such

as Jehovah’s Witnesses and those who identify specific requests on their

advance directives or living will.

HYPERTENSION AND DYSRHYTHMIAS

Hypertension

is common in the immediate postoperative period secondary to sympathetic

nervous system stimulation from pain, hypoxia, or bladder distention.

Dysrhythmias are associated with electrolyte imbalance, altered respiratory

function, pain, hypo-thermia, stress, and anesthetic medications. Both

conditions are managed by treating the underlying causes.

Relieving Pain and Anxiety

Opioid

analgesics are administered judiciously and often intra-venously in the PACU

(Meeker & Rothrock, 1999). Intravenous opioids provide immediate relief and

are short-acting, thus min-imizing the potential for drug interactions or

prolonged respira-tory depression while anesthetics are still active in the

patient’s system. In addition to monitoring the patient’s physiologic sta-tus

and managing pain, the PACU nurse provides psychological support in an effort

to relieve the patient’s fears and concerns. The nurse checks the medical

record for special needs and con-cerns of the patient. When the patient’s

condition permits, a close member of the family may visit in the PACU for a few

moments. This often decreases the family’s anxiety and makes the patient feel

more secure.

Controlling Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea

and vomiting are common problems in the PACU. The nurse should intervene at the

patient’s first report of nausea to con-trol the problem rather than wait for

it to progress to vomiting.

Many

medications are available to control nausea and vomit-ing without oversedating

the patient; they are commonly ad-ministered during surgery as well as in the

PACU (Meeker & Rothrock, 1999). Intravenous or intramuscular administration

of droperidol (Inapsine) is common, especially in the ambulatory setting. Other

medications such as metoclopramide (Reglan), prochlorperazine (Compazine), and

promethazine (Phenergan) are commonly prescribed (Karch, 2002; Meeker &

Rothrock, 1999). Although it is costly, ondansetron (Zofran) is a frequently

used, effective antiemetic with few side effects.

Gerontologic Considerations

The

elderly patient, like all other patients, is transferred from the operating

room table to the bed or stretcher slowly and gently. The effects of this

action on blood pressure and ventilation are monitored. Special attention is

given to keeping the patient warm because the elderly are more susceptible to

hypothermia. The pa-tient’s position is changed frequently to stimulate

respirations and to promote circulation and comfort.

Immediate

postoperative care for the elderly patient is the same as that for any surgical

patient, but additional support is given if there is impaired cardiovascular,

pulmonary, or renal function. With invasive monitoring, it is possible to

detect cardio-pulmonary deficits before signs and symptoms are apparent. The

elderly patient has less physiologic reserve, and physiologic re-sponses to

stress are diminished or slowed. These changes re-inforce the need for close

monitoring and prompt treatment of hypotension, shock, and hemorrhage. Because

of monitoring and improved individualized preoperative preparation, many older

adults tolerate surgery well and have an uneventful recovery.

Postoperative

confusion is common in older patients. The confusion is aggravated by social

isolation, restraints, anesthetics and analgesics, and sensory deprivation.

Reorienting the patient to the environment and using smaller amounts of

sedatives, anes-thetics, and analgesics may help prevent confusion. However,

un-relieved pain, particularly pain at rest, may increase the risk for delirium

and must be addressed (Lynch, Lazor, Gellis et al., 1998). Hypoxia can present

as confusion and restlessness, as can blood loss and electrolyte imbalance.

Excluding all other causes of confusion must precede the assumption that

confusion is re-lated to age, circumstances, and medications.

Determining Readiness for Discharge From the PACU

A patient remains in the PACU until he or she has fully recov-ered from the anesthetic agent (Meeker & Rothrock, 1999). Indicators of recovery include stable blood pressure, adequate res-piratory function, adequate oxygen saturation level compared with baseline, and spontaneous movement or movement on com-mand. Usually the following measures are used to determine the patient’s readiness for discharge from the PACU:

·

Stable vital signs

·

Orientation to person, place,

events, and time

·

Uncompromised pulmonary function

·

Pulse oximetry readings indicating

adequate blood oxygen saturation

·

Urine output at least 30 mL/h

·

Nausea and vomiting absent or under

control

·

Minimal pain

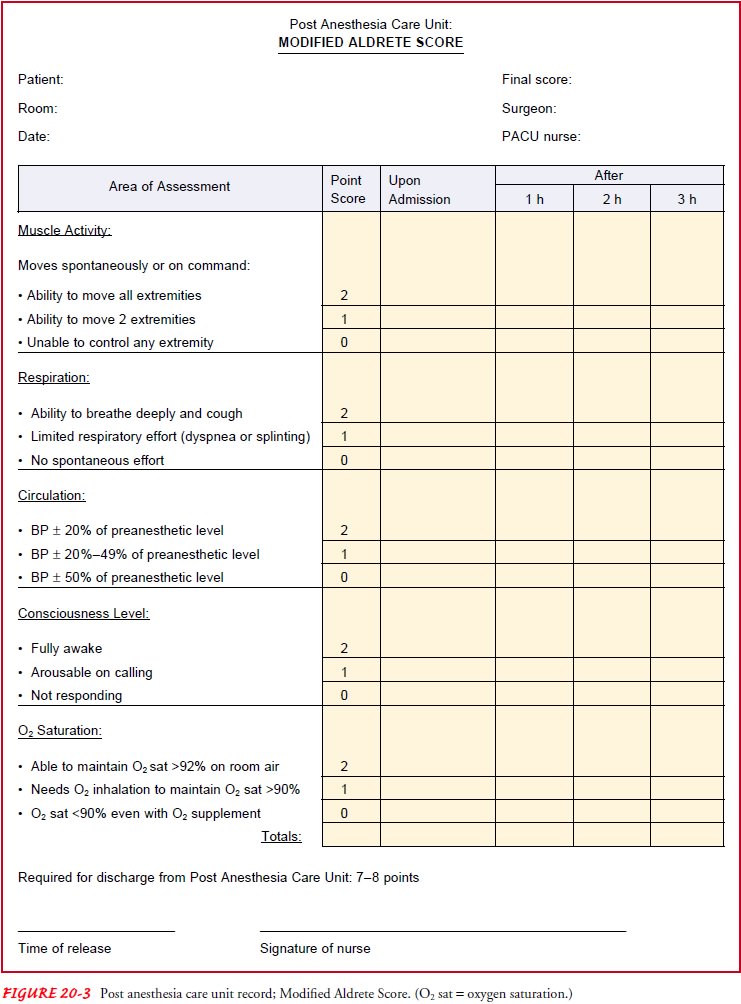

Many hospitals use a scoring system (eg, Aldrete score) to de-termine the patient’s general condition and readiness for transfer from the PACU (Quinn, 1999). Throughout the recovery pe-riod, the patient’s physical signs are observed and evaluated by means of a scoring system based on a set of objective criteria. This evaluation guide, a modification of the Apgar scoring system used for evaluating newborns, allows a more objective assessment of the patient’s condition in the PACU (Fig. 20-3). The patient is assessed at regular intervals (eg, every 15 or 30 minutes), and the score is totaled on the assessment record. Patients with a score lower than 7 must remain in the PACU until their condition improves or they are transferred to an intensive care area, depend-ing on their preoperative baseline scores.

The

patient is discharged from the phase I PACU by the anes-thesiologist or

anesthetist to the critical care unit, the medical-surgical unit, the phase II

PACU, or home with a responsible family member (Quinn, 1999). Patients being

discharged directly to home require verbal and written instructions and

information about follow-up care.

Promoting Home and Community-Based Care

To

ensure patient safety and recovery, expert patient teaching and discharge

planning are necessary when a patient undergoes same-day or ambulatory surgery.

Because anesthetics cloud memory for concurrent events, instructions should be

given to both the pa-tient and the adult who will be accompanying the patient

home (Quinn, 1999).

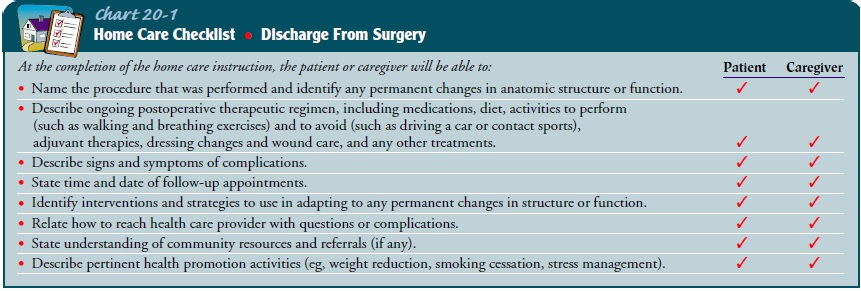

TEACHING PATIENTS SELF-CARE

The

patient and caregiver (eg, family member or friend) are in-formed about

expected outcomes and immediate postoperative changes anticipated in the

patient’s capacity for self-care (Fox, 1998; Quinn, 1999). Written instructions

about wound care, ac-tivity and dietary recommendations, medication, and

follow-up visits to the same-day surgery unit or the surgeon are provided.

Written instructions (designed to be copied and given to patients) about the

postoperative care following many types of surgery are usually provided

(Economou & Economou, 1999). The patient’s caregiver at home is provided

with verbal and written instructions about what to observe the patient for and

about the actions to take if complications occur. Prescriptions are given to

the patient. The nurse or surgeon’s telephone number is provided, and the

patient and caregiver are encouraged to call with questions and to schedule

follow-up appointments (Chart 20-1).

Although

recovery time varies depending on the type and ex-tent of surgery and the

patient’s overall condition, instructions usually advise limited activity for

24 to 48 hours. During this time, the patient should not drive a vehicle, drink

alcoholic bev-erages, or perform tasks that require energy or skill. Fluids may

be consumed as desired, and smaller-than-normal amounts are eaten at mealtime.

The patient is cautioned not to make impor-tant decisions at this time because

the medications, anesthesia, and surgery may affect his or her decision-making

ability.

CONTINUING CARE

Although most patients who undergo ambulatory surgery re-cover quickly and without complications, some patients require referral for home care. These may be elderly or frail patients, those who live alone, and patients with other health care prob-lems that may interfere with self-care or resumption of usual ac-tivities. The home care nurse assesses the patient’s physical status (eg, respiratory and cardiovascular status, adequacy of pain management, the surgical incision) and the patient’s and family’s ability to adhere to the recommendations given at the time of discharge. Previous teaching is reinforced as needed. The home care nurse may change surgical dressings, monitor the pa-tency of a drainage system, or administer medications. The pa-tient is assessed for any surgical complications. The patient and family are reminded about the importance of keeping follow-up appointments with the surgeon. Follow-up phone calls from the nurse or surgeon may also be used to assess the patient’s progress and to answer any questions (Fox, 1998; Marley & Swanson, 2001).

Related Topics