Chapter: Business Science : International Business Management : Conflict Management and Ethics in International Business Management

Negotiation

NEGOTIATION

Negotiation is a dialogue intended to resolve

disputes, to produce an agreement upon courses

of action, to bargain for individual or collective advantage, or to craft

outcomes to satisfy various interests. It is the primary method of alternative

dispute resolution.

Negotiation

occurs in business, non-profit organizations and government branches, legal

proceedings, among nations and in personal situations such as marriage,

divorce, parenting, and everyday life.

Etymology

The word

"negotiation" is from the Latin expression, "negotiatus",

past participle of negotiate which means "to carry on business".

Another view of negotiation comprises 4 elements:

Strategy,

process and tools, and tactics. Strategy comprises the top level goals -

typically including relationship and the final outcome. Processes and tools

include the steps that will be followed and the roles taken in both preparing

for and negotiating with the other parties. Tactics include more detailed

statements and actions and responses to others' statements and actions.

Approaches to negotiation

The advocate's approach

In the

advocacy approach, a skilled negotiator usually serves as advocate for one

party to the negotiation and attempts to obtain the most favorable outcomes

possible for that party. In this process the negotiator attempts to determine

the minimum outcome(s) the other party is (or parties are) willing to accept,

then adjusts their demands accordingly. A "successful" negotiation in

the advocacy approach is when the negotiator is able to obtain all or most of

the outcomes their party desires, but without driving the other party to

permanently break off negotiations, unless the best alternative to a negotiated

agreement (BATNA) is acceptable.

Indeed, the ten new rules for global negotiations

advocated by Hernandez and Graham.

Accept only creative outcomes

Understand cultures, especially your own.

Don‘t just adjust to cultural differences, exploit

them.

Gather intelligence and reconnoiter the terrain.

Design the information flow and process of

meetings.

Invest in personal relationships.

Persuade with questions. Seek information and

understanding.

Make no concessions until the end.

Use techniques of creativity

10.Continue

creativity after negotiations

Emotion in negotiation

Emotions

play an important part in the negotiation process, although it is only in

recent years that their effect is being studied. Emotions have the potential to

play either a positive or negative role in negotiation. During negotiations,

the decision as to whether or not to settle rests in part on emotional factors.

Negative emotions can cause intense and even irrational behavior, and can cause

conflicts to escalate and negotiations to break down, while positive emotions

facilitate reaching an agreement and help to maximize joint gains.

Positive effect in negotiation

Even

before the negotiation process starts, people in a positive mood have more confidence,

and higher tendencies to plan to use a cooperative strategy. During the

negotiation, negotiators who are in a positive mood tend to enjoy the

interaction more, show less contentious behavior, use less aggressive tactics

and more cooperative strategies. This in turn increases the likelihood that

parties will reach their instrumental goals, and enhance the ability to find

integrative gains.

Indeed,

compared with negotiators with negative or natural affectivity, negotiators

with positive affectivity reached more agreements and tended to honor those

agreements more. Those favorable outcomes are due to better Decision Making

processes, such as flexible thinking, creative Problem Solving, respect for

others' perspectives, willingness to take risks and higher confidence.

Post

negotiation positive affect has beneficial consequences as well. It increases

satisfaction with achieved outcome and influences one‘s desire for future

interactions. The PA aroused by reaching an agreement facilitates the dyadic

relationship, which result in affective commitment that sets the stage for

subsequent interactions. PA also has its drawbacks: it distorts perception of

self performance, such that performance is judged to be relatively better than

it actually is. Thus, studies involving self reports on achieved outcomes might

be biased.

Negative effect in negotiation

Negative

effect has detrimental effects on various stages in the negotiation process.

Although various negative emotions affect negotiation outcomes, by far the most

researched is anger. Angry negotiators plan to use more competitive strategies

and to cooperate less, even before the negotiation starts. These competitive

strategies are related to reduce joint outcomes. During negotiations, anger

disrupts the process by reducing the level of trust, clouding parties'

judgment, narrowing parties' focus of attention and changing their central goal

from reaching agreement to retaliating against the other side. Angry

negotiators pay less attention to opponent‘s interests and are less accurate in

judging their interests, thus achieve lower joint gains.

Moreover,

because anger makes negotiators more self-centered in their preferences, it

increases the likelihood that they will reject profitable offers. Anger doesn‘t

help in achieving negotiation goals either: it reduces joint gains and does not

help to boost personal gains, as angry negotiators don‘t succeed in claiming

more for themselves. Moreover, negative emotions leads to acceptance of

settlements that are not in the positive utility function but rather have a

negative utility. However, expression of negative emotions during negotiation

can sometimes be beneficial: legitimately expressed anger can be an effective

way to show one's commitment, sincerity, and needs.

Moreover,

although NA reduces gains in integrative tasks, it is a better strategy than PA

in distributive tasks (such as zero-sum). In his work on negative affect

arousal and white noise, Seidner found support for the existence of a negative

affect arousal mechanism through observations regarding the devaluation of

speakers from other ethnic origins." Negotiation may be negatively

affected, in turn, by submerged hostility toward an ethnic or gender group.

Conditions for emotion effect in negotiation

Research

indicates that negotiator‘s emotions do not necessarily affect the negotiation

process. Albarracın et al. (2003) suggested that there are two conditions for

emotional effect, both related to the ability (presence of environmental or

cognitive disturbances) and the motivation:

Identification of the affect: requires high

motivation, high ability or both.

Determination that the affect is relevant and

important for the judgment: requires that either the motivation, the ability or

both are low.

According

to this model, emotions are expected to affect negotiations only when one is

high and the other is low. When both ability and motivation are low the affect

will not be identified, and when both are high the affect will be identify but

discounted as irrelevant for judgment. A possible implication of this model is,

for example, that the positive effects PA has on negotiations (as described

above) will be seen only when either motivation or ability are low.

Cultural

differences cause four kinds of problems in international business

negotiations, at the levels of:

Language

Nonverbal

behaviors

Values

Thinking

and decision-making processes

The order

is important; the problems lower on the list are more serious because they are

more subtle. For example, two negotiators would notice immediately if one were

speaking Japanese and the other German. The solution to the problem may be as

simple as hiring an interpreter or talking in a common third language, or it

may be as difficult as learning a language. Regardless of the solution, the

problem is obvious.

Nonverbal Behaviors

Anthropologist

Ray L. Birdwhistell demonstrated that less than 35% of the message in

conversations is conveyed by the spoken word while the other 65% is

communicated nonverbally. Albert Mehrabian, a UCLA psychologist, also parsed

where meaning comes from in face-to-face interactions. He reports:

7% of the

meaning is derived from the words spoken

38% from

paralinguistic channels, that is, tone of voice, loudness, and other aspects of

how things are said 55% from facial

expressions

Of

course, some might quibble with the exact percentages (and many have), but our

work also supports the notion that nonverbal behaviors are crucial – how things

are said is often more important than what is said.

Exhibit 2

provides analyses of some linguistic aspects and nonverbal behaviors for the 15

videotaped groups, that is, how things are said. Although these efforts merely

scratch the surface of these kinds of behavioral analyses, they still provide

indications of substantial cultural differences.

Differences in managerial values as pertinent to

negotiations

Four

managerial values objectivity, competitiveness, equality, and punctuality that

are held strongly and deeply by most Americans seem to frequently cause misunderstandings

and bad feelings in international business negotiations.

Objectivity

Americans

make decisions based upon the bottom line and on cold, hard facts. Americans

don‘t play favorites. Economics and performance count, not people. Business is

business. Such statements well reflect American notions of the importance of

objectivity.

The

single most successful book on the topic of negotiation, Getting to Yes, is

highly recommended for both American and foreign readers. The latter will learn

not only about negotiations but, perhaps more important, about how Americans

think about negotiations. The authors are quite emphatic about separating the

people from the problem, and they state, every negotiator has two kinds of

interests: in the substance and in the relationship. This advice is probably

quite worthwhile in the United States or perhaps in Germany, but in most places

in the world such advice is nonsense. In most places in the world, particularly

in collectivistic, high-context cultures, personalities and substance are not

separate issues and cannot be made so.

Competitiveness and Equality

Simulated

negotiations can be viewed as a kind of experimental economics wherein the

values of each participating cultural group are roughly reflected in the economic

outcomes. The simple simulation used in this part of our work represents the

essence of commercial negotiations it has both competitive and cooperative

aspects. At least 40 businesspeople from each culture played the same

buyer-seller game, negotiating over the prices of three products. Depending on

the agreement reached, the ―negotiation pie could be made larger through

cooperation (as high as $10,400 in joint profits) before it was divided between

the buyer and seller.

Time

Just make

them wait. Everyone else in the world knows that no negotiation tactic is more

useful with Americans, because no one places more value on time, no one has

less patience when things slow down, and no one looks at their wristwatches

more than Americans do. Edward T. Hall in his seminal writing is best at

explaining how the passage of time is viewed differently across cultures and

how these differences most often hurt Americans.

Differences in thinking and decision-making

processes

When

faced with a complex negotiation task, most Westerners (notice the

generalization here) divide the large task up into a series of smaller tasks.

Issues such as prices, delivery, warranty, and service contracts may be settled

one issue at a time, with the final agreement being the sum of the sequence of

smaller agreements. In Asia, however, a different approach is more often taken

wherein all the issues are discussed at once, in no apparent order, and

concessions are made on all issues at the end of the discussion. The Western

sequential approach and the Eastern holistic approach do not mix well.

Negotiation Theory

Common Assumptions of Most Theories

Negotiation

is a specialized and formal version of conflict resolution most frequently

employed when important issues must be agreed upon. Negotiation is necessary

when one party requires the other party's agreement to achieve its aim. The aim

of negotiating is to build a shared environment leading to longterm trust and

often involves a third, neutral party to extract the issues from the emotions

and keep the individuals concerned focused. It is a powerful method for

resolving conflict and requires skill and experience. Zartman defines

negotiation as "a process of combining conflicting positions into a common

position under a decision rule of unanimity, a phenomenon in which the outcome

is determined by the process."

However,

most theories of negotiations share the notion of negotiations as a process.

Yet, they differ in their description of the process. Structural Analysis

considers this process to be a power game. Strategic analysis thinks of it as a

repetition of games (Game Theory). Integrative Analysis prefers the more

intuitive notion of process, in which negotiations undergo successive stages,

e.g. pre-negotiation, stalemate, settlement. Especially structural, strategic

and procedural analysis build on rational actors, who are able to prioritize

clear goals, are able to make trade-offs between conflicting values, are

consistent in their behavioral pattern, and are able to take uncertainty into

account.

Negotiations

differ from mere coercion, in that negotiating parties have the theoretic

possibility to withdraw from negotiations. It is easier to study bi-lateral

negotiations, as opposed to multilateral negotiations.

Structural Analysis

Structural

Analysis is based on a distribution of empowering elements among two

negotiating parties. Structural theory moves away from traditional Realist

notions of power in that it does not only consider power to be a possession,

manifested for example in economic or military resources, but also thinks of

power as a relation.

Based on

the distribution of elements, in structural analysis we find either

power-symmetry between equally strong parties or power-asymmetry between a

stronger and a weaker party. All elements from which the respective parties can

draw power constitute

Structure.

They may be of material nature, i.e. hard power, (such as weapons) or of social

nature, i.e. soft power, (such as norms, contracts or precedents). These

instrumental elements of power, are either defined as parties‘relative position

(resources position) or as their relative ability to make their options

prevail. Structural analysis is easy to criticize, because it predicts that the

strongest will always win. This, however, does not always hold true.

Strategic Analysis

According

to structural analysis, negotiations can therefore be described with matrices,

such as the Prisoner's Dilemma, a concept taken from Game Theory. Another

common game is the Chicken Dilemma.

Strategic

analysis starts with the assumption that both parties have a veto. Thus, in

essence, negotiating parties can cooperate (C) or defect (D). Structural

analysis then evaluates possible outcomes of negotiations (C, C; C, D; D, D; D,

C), by assigning values to each of the possible outcomes. Often, co-operation

of both sides yields the best outcome. The basic problem however is that the

parties can never be sure that the other is going to cooperate, mainly because

of two reasons: first, decisions are made at the same time or, second,

concessions of one side might not be returned. Therefore the parties have

contradicting incentives to cooperate or defect. If one party cooperates or

makes a concession and the other does not, the defecting party might relatively

gain more. Trust may be built only in repetitive games through the emergence of

reliable patterns of behavior such as tit-for-tat.

Process Analysis

Process

analysis is the theory closest to haggling. Parties start from two points and

converge through a series of concessions. As in strategic analysis, both sides

have a veto (e.g. sell, not sell; pay, not pay). Process analysis also features

structural assumptions, because one side may be weaker or stronger (e.g. more

eager to sell, not willing to pay a certain price). Process Analysis focuses on

the study of the dynamics of processes. E.g. both Zeuthen and Cross tried to

find a formula in order to predict the behaviour of the other party in finding

a rate of concession, in order to predict the likely outcome.

The

process of negotiation therefore is considered to unfold between fixed points:

starting point of discord, end point of convergence. The so called security

point, that is the result of optional withdrawal, is also taken into account.

Integrative Analysis

Integrative

analysis divides the process into successive stages, rather than talking about

fixed points. It extends analysis to pre-negotiations stages, in which parties

make first contacts. The outcome is explained as the performance of the actors

at different stages. Stages may include pre-negotiations, finding a formula of

distribution, crest behavior, settlement Disadvantages of International

Business – Conflict in International Business – Sources and Types of Conflict –

Conflict Resolutions – Negotiation – The Role of International Agencies –

Ethical Issues in International Buusiness – Ethical Decision-Making.

Contents

Conflict

in intern ational business Negotiation

International

business ethics

Conflict in Organizations:

Definition

Opposition

Incompatible

behavior Antagonistic inter action

Block

another party from reaching her or his goals

Key elements

Interdepen dence with another party

Perception of incompatible goals

Conflict events

Disagreem ents

o Debates

o Disputes

o Preventin g someone from reaching valued goals

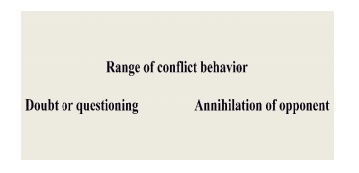

Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict

Functional conflict: works

toward the goals of an organization or group

Dysfunctional conflict: blocks

an organization or group from reaching its goals

Dysfunctional

high conflict: what you typically think about conflict

Dysfunctional

low conflict: A typical view. Levels vary among groups

Functional conflict

“Constructive

Conflict”--Mary Parker Follett (1925) Increases information and ideas

Encourages

innovative thinking

Unshackles

different points of view

Reduces

stagnation

Dysfunctional high conflict

Tension,

anxiety, stress

Drives

out low conflict tolerant people Reduced trust

Poor

decisions because of withheld or distorted information Excessive management

focus on the conflict

Dysfunctional low conflict

Few new

ideas

Poor

decisions from lack of innovation and information Stagnation

Business

as usual

Levels and Types of Conflict

Level of conflict Type of

conflict

Organization Within

and between organizations

Group Within

and between groups

Individual Within

and between individuals

Levels and Types of Conflict

Intra-organization conflict

o Conflict

that occurs within an organization o At interfaces of organization functions

Can occur along the vertical and horizontal

dimensions of the organization

Vertical

conflict: between managers and subordinates

Horizontal

conflict: between departments and work groups

Intra-group conflict

Conflict

among members of a group Early stages of group development

Ways of

doing tasks or reaching group's goals

Intergroup conflict: between

two or more groups

Interpersonal conflict

Between

two or more people

Differences

in views about what should be done Efforts to get more resources

Differences

in orientation to work and time in different parts of an organization Intrapersonal conflict - Occurs within

an individual

Threat to

a person’s values

Feeling

of unfair treatment

Multiple

and contradictory sources of socialization

Related

to the Theory of Cognitive Dissonance and negative inequity

Inter-organization conflict

Between

two or more organizations Not competition

Examples:

suppliers and distributors, especially with the close links now possible

Conflict Episodes

Simple conflict episode

Latent

conflict

Manifest

conflict

Conflict

aftermath

Conflict

reduction

Latent conflict: antecedents of conflict behavior

that can start conflict episode Manifest

conflict: observable conflict behavior

Conflict aftermath

End of a

conflict episode

Often the

starting point of a related episode

Becomes

the latent conflict for another episode Conflict

reduction: lower the conflict level

Latent conflict

The

antecedents of conflict

Example:

scarce resources

Some

latent conflict in the lives of college students

Parking

spaces

Library

copying machines Computer laboratory

Books in

the bookstore

School

and other parts of your life University policies

Manifest conflict

Observable

conflict behavior

Example:

disagreement, discussion

Conflict aftermath

Residue

of a conflict episode

Example:

compromise in allocating scarce resources leaves both parties with less than

they wanted

Perceived conflict

o Become

aware that one is in conflict with another party o Can block out some conflict

o Can perceive conflict when no

latent conditions exist

o Example: misunderstanding another person’s

position on an issue

Felt conflict

o Emotional

part of conflict o Personalizing the conflict o Oral and physical hostility

o Hard to

manage episodes with high felt conflict o What people likely recall about conflict

Conflict Frames and Orientations

Conflict frame

Relationship-Task

Cooperate-Win

Emotional

Intellectual

Conflict frame dimensions

Relationship-Task

Relationship:

focuses on interpersonal relationships Task: focuses on material aspects of an

episode

Emotional-Intellectual

Emotional:

focuses on feelings in the conflict episode (felt conflict) Intellectual:

focuses on observed behavior (manifest conflict)

Cooperate-Win

Cooperate:

emphasizes the role of all parties to the conflict Win: wants to maximize

personal gain

Conflict frames

Limited

research results

End an

episode with a relationship or intellectual frame: feel good about relationship

with other party

Cooperation-focused

people end with more positive results than those focused on winning

Conflict orientations

Dominance:

wants to win; conflict is a battle

Collaborative:

wants to find a solution that satisfies everyone Compromise: splits the

differences

Avoidance:

backs away

Accommodative:

focuses on desires of other party

Reducing Conflict

Lose-lose

methods: parties to the conflict episode do not get what they want Win-lose

methods: one party a clear winner; other party a clear loser Win-win methods:

each party to the conflict episode gets what he or she wants Summary

Lose-lose

methods: compromise Win-lose methods: dominance

Win-win

methods: problem solving

International Business Negotiation

Negotiation is the action and the process of

reaching an agreement by means of exchanging ideas with the intention of dispelling conflicts and enhancing

relationship to satisfy each other’s needs.

Characteristics of negotiation:

Every

negotiation involves two or more parties.

The

objective of a negotiation must be definite.

Negotiation

must be conducted on an equal basis.

A

consensus must be built on the basis of mutual concession.

Negotiation

involves exchange of ideas, communication, persuasion, compromise and suchlike

(process).

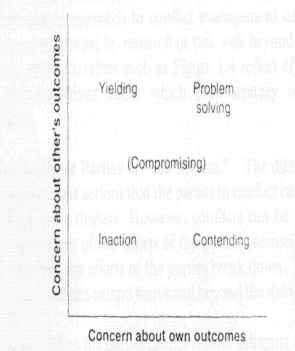

The Dual Concerns Model:

Business negotiation is a proce

ss of conferring in which the participants of business activities communicate, discuss, and adju st

their views, settle differences and finally reach a mutually acceptable

agreement in order to close a deal or achieve a proposed financial go al.

Characteristics of Business Ne gotiation:

The

objective of business negotiation is to obtain financial interest

The core

of business neg otiation is price

(3). Its

principle is equality and mutual benefit

(4).

Items of contract should keep strictly accurate and rigorous.

Principles of business negotiation:

Equality

principle

Cooperation

principle Flexibility principle

Positions-subjected-to-interests

principle

Depersonalizing

principl e (Separating the people from the problem) Using objective criterion

International Business Negotiation is the

business negotiation that takes p ace between the interest groups from different countries or regions.

Features of International Busi ness Negotiation:

Language

barrier

Cultural

differences

International

laws and domestic laws are both in force

International

political factors must be taken into account

The

difficulty and the cost are greater than that of domestic business negotiations

Forms of International Business Negotiation:

Classification

by chief negotiator Classification by negotiation object Classification by form

Classification by procedure

Classification by chief negotiator

Government-

to- government’s negotiation

Government-

to- Business’s negotiation

Producer-

to- Producer’s negotiation

Producer-

to- Trader’s negotiation

Retailer-

to -Producer’s negotiation

Business-

to- Business’s negotiation

Business-

to- Consumer’s negotiation

Classification by negotiation object

(1)Product

trade negotiation (2)Technology trade negotiation

Service

trade negotiation

International

project negotiation

Classification by form:

One- to-

one negotiation

Team

negotiation

Multilateral

negotiation

Classification by procedure

Horizontal

Negotiation

Vertical

Negotiation

The Basic Forms of International Business

Negotiation:

Host

Court” negotiation and “Guest Court” negotiation Oral negotiation and written

negotiation Formal and informal negotiation

“Host Court” negotiation and “Guest Court”

negotiation:

Host-

Court negotiation

Guest-

Court negotiation

Changing-

Court negotiation

Third-

place negotiation

Oral negotiation and written negotiation

Oral

negotiation

Written

negotiation

Formal and Informal negotiation:

Formal

negotiation

Informal

negotiation

International Negotiation:

More

complex than domestic negotiations

Differences

in national cultures and differences in political, legal, and economic systems

often separate potential business partners

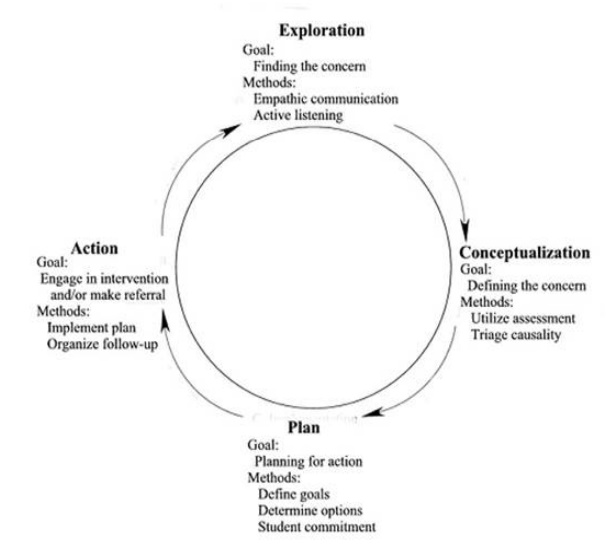

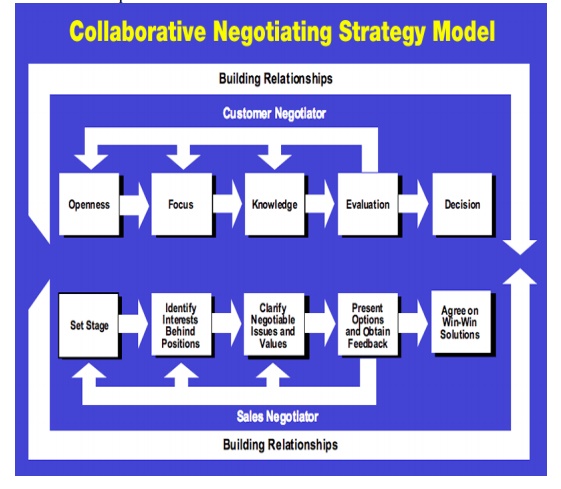

Steps in the International Negotiation process

The successful international negotiator: personal

characteristics

Tolerance

of ambiguous situations Flexibility and creativity

Humor

Stamina Empathy Curiosity Bilingual

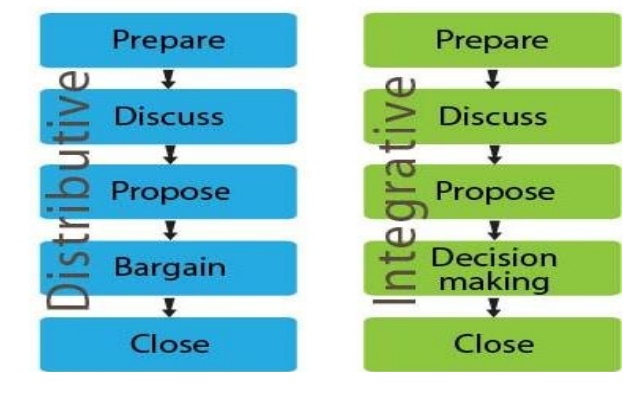

BASIC NEGOTIATION STRATEGIES:

Competitive

The negotiation as a win-lose game Problem solving

Search

for possible win-win situations

Related Topics