Period of Radicalism in Anti-imperialist Struggles | History - Meerut Conspiracy Case, 1929 | 12th History : Chapter 5 : Period of Radicalism in Anti-imperialist Struggles

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 5 : Period of Radicalism in Anti-imperialist Struggles

Meerut Conspiracy Case, 1929

Meerut Conspiracy Case, 1929

Communist Activities

The

Meerut Conspiracy Case of 1929, was, perhaps, the most famous of all the

communist conspiracy cases instituted by the British Government. The late 1920s

witnessed a number of labour upsurges and this period of unrest extended into

the decade of the Great Depression (1929–1939). Trade unionism spread over to

many urban centres and organised labour strikes. The communists played a

prominent role in organising the working class throughout this period. The

Kharagpur Railway workshop strikes in February and September 1927, the Liluah

Rail workshop strike between January and July 1928, the Calcutta scavengers’

strike in 1928, the several strikes in the jute mills in Bengal during

July-August 1929, the strike at the Golden Rock workshop of the South Indian

Railway, Tiruchirappalli, in July 1928, the textile workers’ strike in Bombay

in April 1928 are some of the strikes that deserve mention.

Government Repression

Alarmed

by this wave of strikes and the spread of communist activities, the British

Government brought two draconian Acts - the Trade Disputes Act, 1928 and the

Public Safety Bill, 1928. These Acts armed the government with powers to

curtail civil liberties in general and suppress the trade union activities in

particular. The government was worried about the strong communist influence

among the workers and peasants.

Determined

to wipe out the radical movement, the government resorted to several repressive

measures. They arrested 32 leading activists of the Communist Party, from

different parts of British India like Bombay, Calcutta, Punjab, Poona and

United Provinces. Most of them were trade union activists though not all of

them were members of the Communist Party of India. At least eight of them

belonged to the Indian National Congress. The arrested also included three

British communists-Philip Spratt, Ban Bradley and Lester Hutchinson – who had

been sent by the Communist Party of Great Britain to help build the party in

India. Like those arrested in the Kanpur Conspiracy Case they were charged

under Section 121A of the Indian Penal Code. All the 32 leaders arrested were

brought to Meerut (in United Province then) and jailed. A good deal of

documents that the colonial administration described as ‘subversive material,’

like books, letters, and pamphlets were seized and produced as evidence against

the accused.

The British government conceived of conducting the trial in

Meerut (and not, for instance in Bombay from where a large chunk of the accused

hailed) so that they could get away with the obligations of a jury trial. They

feared a jury trial could create sympathy for the accused.

Trial and Punishment

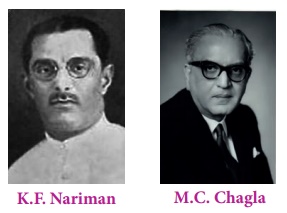

Meanwhile,

a National Meerut Prisoners’ Defence Committee was formed to coordinate defence

in the case. Famous Indian lawyers like K.F. Nariman and M.C. Chagla appeared

in the court on behalf of the accused. Even national leaders like Gandhi and

Jawaharlal Nehru visited the accused in jail. All these show the importance of

the case in the history of our freedom struggle.

The

Sessions Court in Meerut awarded stringent sentences on 16 January 1933, four

years after the arrests in 1929. 27 were convicted and sentenced to various

duration of transportation. During the trial, the Communists made use of their

defence as a platform for propaganda by making political statements. These were

reported widely in the newspapers and thus lakhs of people came to know about

the communist ideology and the communist activities in India. There were

agitations against the conviction. That three British nationals were also

accused in the case, the case became known internationally too. Most

importantly, even Romain Rolland and Albert Einstein raised their voice in

support of the convicted.

Under the national and international pressure, on appeal, the sentences were considerably reduced in July 1933.

Related Topics