Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Medication Compliance

Medication Compliance

Medication Compliance

Introduction

Compliance,

or the degree to which patients’ behaviors coincide with the recommendations of

health care providers, is an important component in the understanding of

patient outcomes, particularly in light of a growing regimen of efficacious and

expensive medical treatments. There is an evident gap between the efficacy of

regimens tested in tightly controlled clinical trials and their effectiveness

when applied to “real world” patient experiences. One explanation for this

“efficacy-effectiveness gap”, when treatment regimens move from efficacy trials

into everyday practice, is the apparent decline in patient compliance. Other

terms closely related to compliance include “adherence”, “fidelity”, and

“maintenance”.

Compliance

is difficult to quantify for several reasons. Completely attributing the

difference between an expected and observed treatment effect to problems with

medication com-pliance may be overly simplistic. Several other factors such as

differences in population, degree of comorbidity with other psy-chiatric or

medical diagnoses, and severity of illness may all ad-versely affect the

potential benefit to the patient. Poor or partial compliance with treatment may

have a variable effect on treat-ment outcomes depending on the pharmacokinetic

profile of the medication in question. For example, occasional missed doses of

very long half-life medications will alter serum drug levels to a lesser extent

than in short half-life compounds. Therefore, the issue of partial compliance

with treatment regimens may become more critical depending on the specific

regimen.

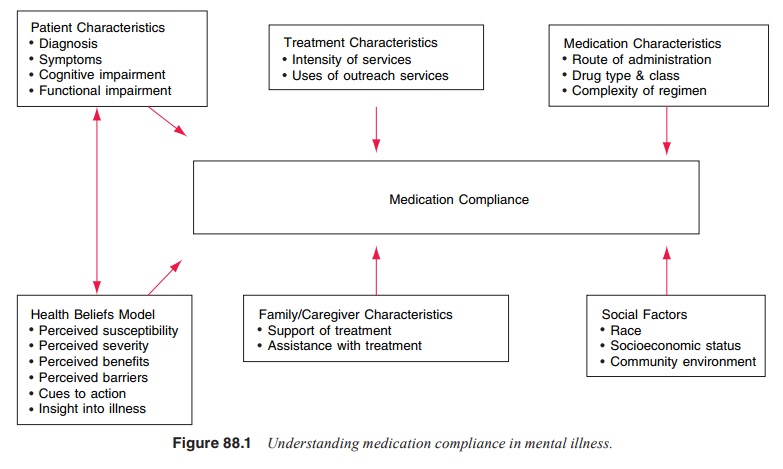

A Theoretical Construct for Compliance: The Health Beliefs Model

The

health beliefs of individuals play a major role in their deci-sion-making

processes regarding participation in recommended treatment. A framework that

may be useful in understanding the complex nature of compliance with medical

regimens is the health beliefs model (HBM). Derived from social psychological

theories of Kurt Lewin, the HBM is grounded in the phenom-enological

orientation of perception driving action (Rosenstock, 1974). While this model

was originally designed to study the utilization of screening tests for

detection of asymptomatic diseases, it has been adapted to the areas of

medication compli-ance among psychiatric patients (Kelly et al. 1987).

Five

components of the HBM apply directly to issues of patient compliance. Figure

88.1 depicts the relationship between these components and ultimate compliance

with treatment.

Susceptibility:

patients must see themselves as vulnerable to a serious illness.

·

Severity: patients must realize that he/she has an

illness with health consequences that will continue without medical attention.

·

Perceived benefits: patients must recognize that an

effective treatment exists for their condition. Benefits from psycho-tropic

medication treatment may include the understanding that treatment ameliorates

mental problems or helps avoid rehospitalization.

·

Barriers: common barriers to pharmacologic

interventions in-volve access to medication, adequate psychiatric follow-up,

and adverse effects from the medication.

·

Cues to action: lastly, patients must experience an

internal or external motivation or “cue” to engage in the specified action that

may benefit them.

Cues that

may trigger a patient to participate in their medica-tion regimen typically

relate to a return of symptoms attributed to their mental illness such as

anxious, depressive, or psychotic states.

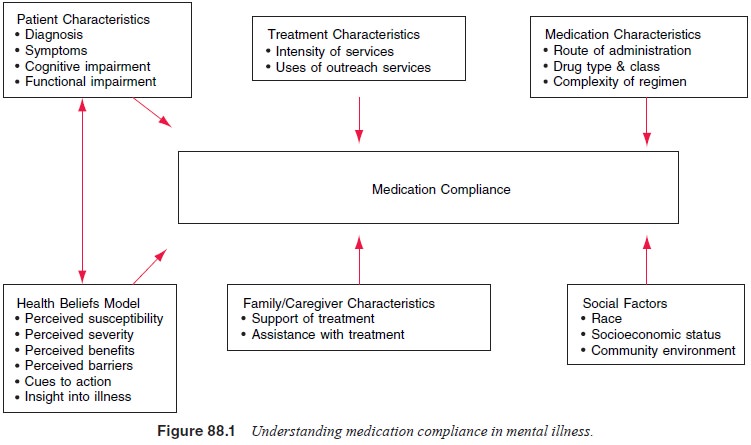

Another Conceptual Model of Compliance

Another

approach to understanding compliance behavior involves the categorization of

problems with compliance along the three domains of psychological problems,

planning problems, and medical problems. These three domains have been used to

develop a compliance checklist as seen in Table 88.1 (Corrigan et al., 1990, Cramer 1991). Psychological

problems include issues such as nonacceptance of

diagnosis or treatment, negative emotional reactions or negative thoughts, and

social criticism from family or friends. Problems

with planning consist of forgetting to take medications, disruption of

usual schedules, and issues with availability of medication. Medical problems that affect compliance include adverse reactions, exacerbation of illness that leads to incapacity to

administer or tolerate medications, or perceptions that medications may lack

efficacy in a given individual. Both HBM and the compliance checklist provide

useful starting points to begin the analysis of problems with compliance in

specific patients or patient populations.

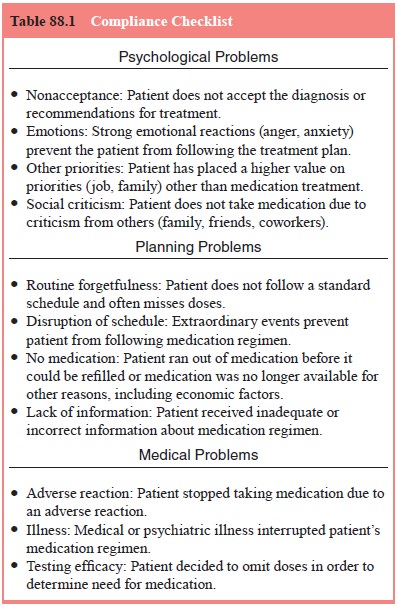

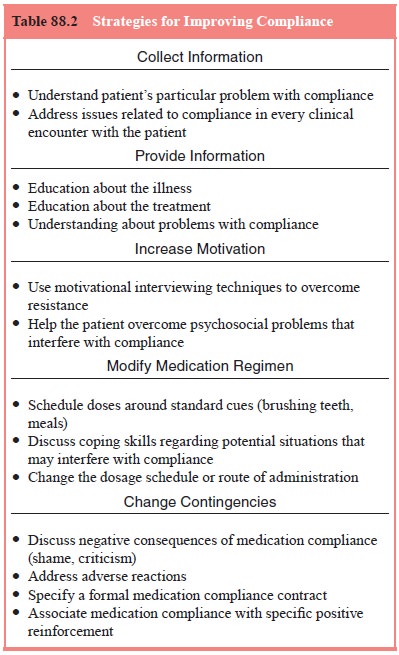

Interventions to Enhance Compliance

General

strategies to enhance compliance take many forms and can be tailored to the

specific needs identified in individual pa-tients. Most approaches to enhance

compliance involve the intro-duction of techniques to improve outpatients’

self-administration of oral medication therapies. Cramer (1991) identifies

several strategies to approach problems with compliance (Table 88.2).

The

action of monitoring compliance itself may improve adherence to proposed

medical regimens, just as frequent weight monitoring may promote weight loss

even without a specific diet regimen. Some data indicate that compliance rates

improve sig-nificantly when outpatients with psychiatric disorders are given

continuous feedback on their medication dosing (Cramer and Rosenheck, 1999).

Compliance-enhancement

interventions that have been studied include individual, group and family

formats and involve diverse theoretical orientations. Unfortunately, many of

the studies that investigate compliance therapies do not also assess the distal

impact on treatment outcomes leaving the clinician unable to evaluate whether

marginal improvements in compliance would in fact lead to cost-effective

improvement in treatment outcomes.

One

intervention referred to as compliance

therapy utilizes a specific approach to individual or group psychotherapy

with cognitive therapy and motivational interviewing techniques (Goldstein,

1992; Hayward et al, 1995).

Therapists attempt to help the patients form a cognitive link between

discontinuation of medication treatment and relapse of symptoms. Using the

patient’s frame of reference, therapists seek to instill a sense of cognitive

dissonance between discontinuation of medication and achievement of the

patient’s own goals. Problem-solving techniques are also employed to identify

internal and external cues that may compromise future medication compliance.

Other

psychosocial interventions to increase compliance in patients with

schizophrenia have also been demonstrated to be effective. Kelly and Scott

(1990) found that strategies aimed at ed-ucation of patients’ families about

compliance and those directed at patients themselves both improved compliance.

No significant difference between the two interventions could be demonstrated.

It is important to note that, given the multiple factors associated with

clinical course, not all improvement in treatment outcomes in schizophrenia is

directly attributable to improved medication compliance. Psychosocial

interventions that lack a specific fo-cus on treatment compliance may

nonetheless have salutatory effects on patient outcomes, regardless of changes

in compliance behavior. Zhang and colleagues (1994) found that family therapy

without a specific focus on compliance produced improvement in relapse rates in

schizophrenic patients independent of changes in medication compliance.

Another

approach to increasing compliance involves the change in route of

administration of medication from oral

preparationsthatmustbetakenatleastoncedailytodepotinjections, such as

haloperidol decanoate and fluphenazine decanoate, that are typically administered

every 2 to 4 weeks. The advantages to depot preparations include supervised

administration of the medication by health care providers, decreased

variability in serum concentrations of the active medication, and no

significant difference in adverse effects as compared with similar oral agents.

Disadvantages include the limited number of medications available in depot

form, the difficulty of scheduling potentially more frequent clinic visits for

injections, and the increased cost

in clinic

staffs’ time with administration of the treatments. At the time of this

publication, no atypical antipsychotic agents were available in depot form.

Therefore, a comparison of compliance with conventional depot agents and

atypical oral agents may be limited in utility. Few studies of depot

antipsychotic preparations address the issues of long-term compliance and

differences in health outcomes when compared with oral agents (Adams and

Eisenbruch, 2002; Quraishi and David, 2002). However, some evidence suggests

that depot antipsychotic agents do confer a marginal improvement in reducing

relapse rates (Glazer and Kane, 1992).

Related Topics