Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Mood Disorders

Major Depressive Disorder

MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Major depressive disorder typically involves 2 or more weeks of a

sad mood or lack of interest in life activities with at least four other

symptoms of depression such as anhedonia and changes in weight, sleep, energy,

concen-tration, decision making, self-esteem, and goals. Major depression is

twice as common in women and has a 1.5 to 3 times greater incidence in

first-degree relatives than in the general population. Incidence of depression

decreases with age in women and increases with age in men. Single and divorced

people have the highest incidence. Depres-sion in prepubertal boys and girls

occurs at an equal rate (Kelsoe, 2005).

Onset and Clinical Course

An untreated episode of depression can last 6 to 24 months before

remitting. Fifty to sixty percent of people who have one episode of depression

will have another. After a sec-ond episode of depression, there is a 70% chance

of recur-rence. Depressive symptoms can vary from mild to severe. The degree of

depression is comparable with the person’s sense of helplessness and

hopelessness. Some people with severe depression (9%) have psychotic features

(APA, 2000).

Treatment and Prognosis

Psychopharmacology

Major categories of antidepressants include cyclic

antide-pressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selec-tive serotonin

reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and atypical antidepressants. The choice of which

antidepressant to use is based on the cli-ent’s symptoms, age, and physical health

needs; drugs that have or have not worked in the past or that have worked for a

blood relative with depression; and other medica-tions that the client is

taking.

Researchers believe that levels of neurotransmitters, especially

norepinephrine and serotonin, are decreased in depression. Usually, presynaptic

neurons release these neurotransmitters to allow them to enter synapses and

link with postsynaptic receptors. Depression results if too few

neurotransmitters are released, if they linger too briefly in synapses, if the

releasing presynaptic neurons reabsorb them too quickly, if conditions in

synapses do not support linkage with postsynaptic receptors, or if the number

of postsynaptic receptors has decreased. The goal is to increase the efficacy

of available neurotransmitters and the absorption by postsynaptic receptors. To

do so, antide-pressants establish a blockade for the reuptake of

norepi-nephrine and serotonin into their specific nerve terminals. This permits

them to linger longer in synapses and to be more available to postsynaptic

receptors. Antidepressants also increase the sensitivity of the postsynaptic

receptor sites (Rush, 2005).

In clients who have acute depression with psychotic features, an

antipsychotic is used in combination with an antidepressant. The antipsychotic

treats the psychotic fea-tures; several weeks into treatment, the client is

reassessed to determine whether the antipsychotic can be withdrawn and the

antidepressant maintained.

Evidence is increasing that antidepressant therapy should continue

for longer than the 3 to 6 months origi-nally believed necessary. Fewer

relapses occur in people with depression who receive 18 to 24 months of

antide-pressant therapy. As a rule, the dosage of antidepressants should be

tapered before being discontinued.

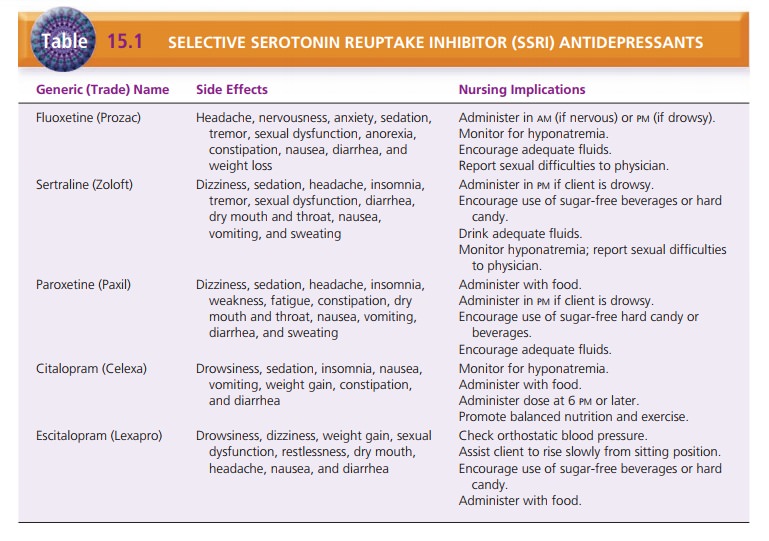

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. SSRIs, the newest category of antidepressants

(Table 15.1), are effective for most clients. Their action is specific to

serotonin reuptake inhibition; these drugs produce few sedating, anticholinergic,

and cardiovascular side effects, which make them safer for use in older adults.

Because of their low side effects and relative safety, people using SSRIs are

more apt to be compli-ant with the treatment regimen than clients using more

trou-blesome medications. Insomnia decreases in 3 to 4 days, appetite returns

to a more normal state in 5 to 7 days, and energy returns in 4 to 7 days. In 7

to 10 days, mood, concen-tration, and interest in life improve.

Fluoxetine (Prozac) produces a slightly higher rate of mild

agitation and weight loss but less somnolence. It has a half-life of more than

7 days, which differs from the 25-hour half-life of other SSRIs.

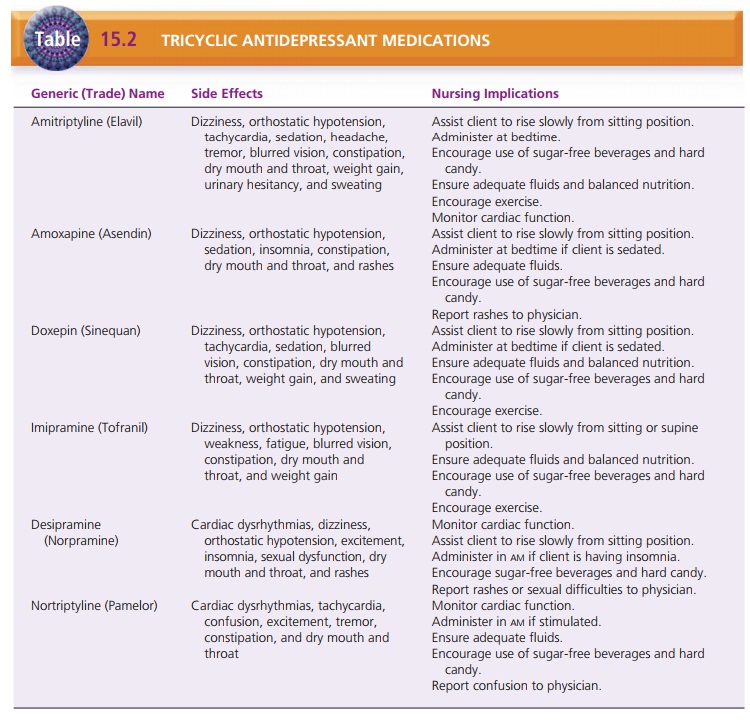

Cyclic Antidepressants. Tricyclics, introduced for

the treat-ment of depression in the mid-1950s, are the oldest antidepressants.

They relieve symptoms of hopelessness, helplessness, anhedonia, inappropriate

guilt, suicidal ide-ation, and daily mood variations (cranky in the morning and

better in the evening). Other indications include panic disor-der,

obsessive–compulsive disorder, and eating disorders. Each drug has a different

degree of efficacy in blocking the activity of norepinephrine and serotonin or

increasing the sensitivity of postsynaptic receptor sites. Tricyclic and

hetero-cyclic antidepressants have a lag period of 10 to 14 days before

reaching a serum level that begins to alter symptoms; they take 6 weeks to

reach full effect. Because they have a long serum half-life, there is a lag

period of 1 to 4 weeks be-fore steady plasma levels are reached and the

client’s symp-toms begin to decrease. They cost less primarily because they

have been around longer and generic forms are available.

Tricyclic antidepressants are contraindicated in severe impairment

of liver function and in myocardial infarction (acute recovery phase). They

cannot be given concurrently with MAOIs. Because of their anticholinergic side

effects, tricyclic antidepressants must be used cautiously in clients who have

glaucoma, benign prostatic hypertrophy, urinary retention or obstruction,

diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroid-ism, cardiovascular disease, renal impairment,

or respira-tory disorders (Table 15.2).

Overdosage of tricyclic antidepressants occurs over sev-eral days

and results in confusion, agitation, hallucinations, hyperpyrexia, and

increased reflexes. Seizures, coma, and cardiovascular toxicity can occur with

ensuing tachycardia, decreased output, depressed contractility, and

atrioventricular block. Because many older adults have concomitant health

problems, cyclic antidepressants are used less often in the geriatric

population than newer types of antidepressants that have fewer side effects and

less drug interactions.

Tetracyclic Antidepressants. Amoxapine (Asendin) may cause extrapyramidal

symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. It can create

tolerance in 1 to 3 months. It increases appetite and causes weight gain and

cravings for sweets.

Maprotiline (Ludiomil) carries a risk for seizures (espe-cially in

heavy drinkers), severe constipation and urinary retention, stomatitis, and

other side effects; this leads to poor compliance. The drug is started and

withdrawn grad-ually. Central nervous system depressants can increase the

effects of this drug.

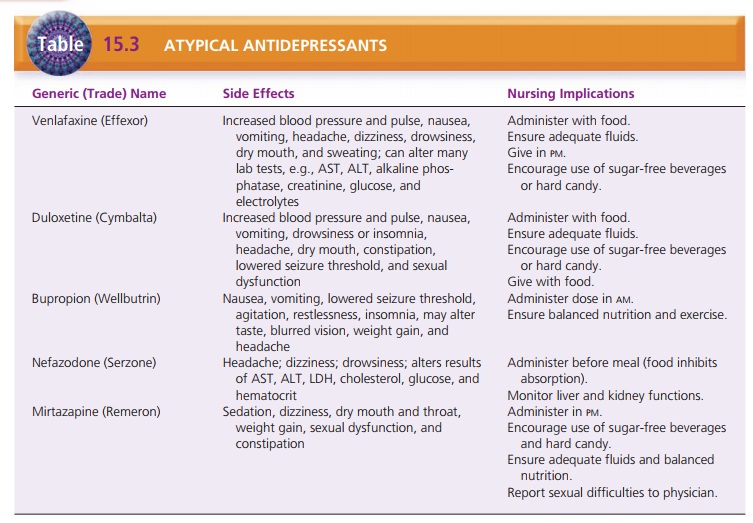

Atypical Antidepressants. Atypical antidepressants are used when the client has an

inadequate response to or side effects from SSRIs. Atypical antidepressants

include venla-faxine (Effexor), duloxetine (Cymbalta), bupropion (Well-butrin),

nefazodone (Serzone), and mirtazapine (Remeron) (Table 15.3).

Venlafaxine blocks the reuptake of serotonin, norepineph-rine, and dopamine (weakly). Duloxetine selectively blocks both serotonin and norepinephrine. Bupropion modestly inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine, weakly inhibits the reuptake of dopamine, and has no effects on serotonin. Bupropion is marketed as Zyban for smoking cessation.

Nefazodone inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and nor-epinephrine

and has few side effects. Its half-life is 4 hours, and it can be used in

clients with liver and kidney disease. It increases the action of certain

benzodiazepines (alprazo-lam, estazolam, and triazolam) and the H2 blocker

terfen-adine. Remeron also inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and

norepinephrine, and it has few sexual side effects; how-ever, its use comes

with a higher incidence of weight gain, sedation, and anticholinergic side

effects (Facts and Comparisons, 2009).

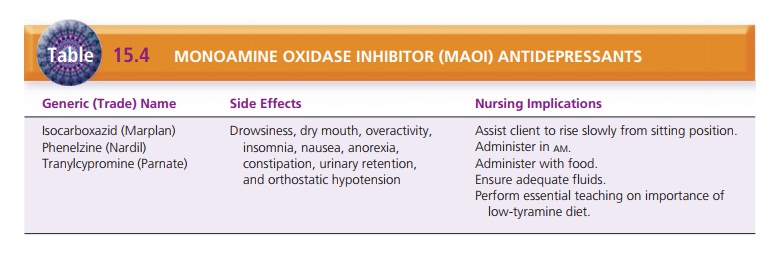

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors. MAOIs are used infre-quently

because of potentially fatal side effects and interac-tions with numerous

drugs, both prescription and over-the-counter preparations (Table 15.4). The

most seri-ous side effect is hypertensive

crisis, a life-threatening con-dition that can result when a client taking

MAOIs ingests tyramine-containing foods

and flu-ids or other medications. Symptoms are occipital headache,

hypertension, nausea, vomiting, chills, sweating, restless-ness, nuchal

rigidity, dilated pupils, fever, and motor agita-tion. These can lead to

hyperpyrexia, cerebral hemorrhage, and death. The MAOI–tyramine interaction

produces symp-toms within 20 to 60 minutes after ingestion. For hypertensive

crisis, transient antihypertensive agents, such as phentolamine mesylate, are

given to dilate blood vessels and decrease vascu-lar resistance (Facts and

Comparisons, 2009).

There is a 2- to 4-week lag period before MAOIs reach therapeutic

levels. Because of the lag period, adequate washout periods of 5 to 6 weeks are

recommended between the times that the MAOI is discontinued and another class

of antidepressant is started.

Other Medical Treatments and Psychotherapy

Electroconvulsive Therapy. Psychiatrists may use electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) to treat depression in selectgroups, such as

clients who do not respond to antidepres-sants or those who experience

intolerable side effects at therapeutic doses (particularly true for older

adults). In addition, pregnant women can safely have ECT with no harm to the

fetus. Clients who are actively suicidal may be given ECT if there is concern

for their safety while waiting weeks for the full effects of antidepressant

medication.

ECT involves application of electrodes to the head of the client to

deliver an electrical impulse to the brain; this causes a seizure. It is

believed that the shock stimulates brain chemistry to correct the chemical

imbalance of depression. Historically, clients did not receive any anes-thetic

or other medication before ECT, and they had full-blown grand mal seizures that

often resulted in injuries ranging from biting the tongue to breaking bones.

ECT fell into disfavor for a period and was seen as “barbaric.” Today, although

ECT is administered in a safe and humane way with almost no injuries, there are

still critics of the treatment.

Clients usually receive a series of 6 to 15 treatments scheduled

thrice a week. Generally, a minimum of six treatments are needed to see

sustained improvement in depressive symptoms. Maximum benefit is achieved in 12

to 15 treatments.

Preparation of a client for ECT is similar to preparation for any

outpatient minor surgical procedure: The client receives nothing by mouth (or,

is NPO) after midnight, removes any fingernail polish, and voids just before

the procedure. An intravenous line is started for the adminis-tration of

medication.

Initially, the client receives a short-acting anesthetic so he or

she is not awake during the procedure. Next, he or she receives a muscle

relaxant/paralytic, usually succinylcho-line, which relaxes all muscles to

reduce greatly the outwardsigns of the seizure (e.g., clonic–tonic muscle

contractions). Electrodes are placed on the client’s head: one on either side

(bilateral) or both on one side (unilateral). The electrical stimulation is

delivered, which causes seizure activity in the brain that is monitored by an

electroencephalogram, or EEG. The client receives oxygen and is assisted to

breathe with an Ambu bag. He or she generally begins to waken after a few

minutes. Vital signs are monitored, and the client is assessed for the return

of a gag reflex.

After ECT treatment, the client may be mildly confused or briefly

disoriented. He or she is very tired and often has a headache. The symptoms are

just like those of anyone who has had a grand mal seizure. In addition, the

client will have some short-term memory impairment. After a treatment, the

client may eat as soon as he or she is hungry and usually sleeps for a period.

Headaches are treated symptomatically.

Unilateral ECT results in less memory loss for the cli-ent, but

more treatments may be needed to see sustained improvement. Bilateral ECT

results in more rapid improve-ment but with increased short-term memory loss.

The literature continues to be divided about the effective-ness of

ECT. Some studies report that ECT is as effective as medication for depression,

whereas other studies report only short-term improvement. Likewise, some

studies report that memory loss side effects of ECT are short lived, whereas

oth-ers report they are serious and long term (Fenton, Fasula, Ostroff, &

Sanacora, 2006; Ross, 2006).

ECT is also used for relapse prevention in depression. Clients may

continue to receive treatments, such as one per month, to maintain their mood

improvement. Often, clients are given antidepressant therapy after ECT to

pre-vent relapse. Studies have found maintenance ECT to be effective in relapse

prevention (Frederikse, Petrides, & Kellner, 2006).

Psychotherapy. A combination of

psychotherapy and medications is considered the most effective

treatment for depressive disorders. There is no one specific type of ther-apy

that is better for the treatment of depression (Rush, 2005). The goals of

combined therapy are symptom remis-sion, psychosocial restoration, prevention

of relapse or recurrence, reduced secondary consequences such as marital

discord or occupational difficulties, and increasing treatment compliance.

Interpersonal therapy focuses on difficulties in relation-ships,

such as grief reactions, role disputes, and role tran-sitions. For example, a

person who, as a child, never learned how to make and trust a friend outside

the family structure has difficulty establishing friendships as an adult.

Interpersonal therapy helps the person to find ways to accomplish this

developmental task.

Behavior therapy seeks to increase the frequency of the client’s

positively reinforcing interactions with the envi-ronment and to decrease

negative interactions. It also may focus on improving social skills.

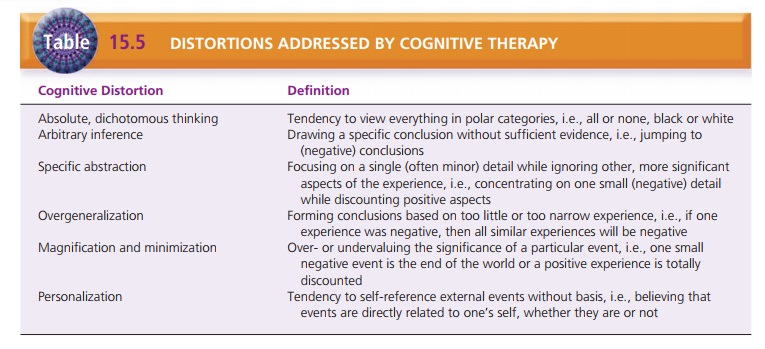

Cognitive therapy focuses on how the person thinks about the self,

others, and the future and interprets his or her experiences. This model

focuses on the person’s distorted thinking, which, in turn, influences

feelings, behavior, and functional abilities. Table 15.5 describes the

cognitive distor-tions that are the focus of cognitive therapy.

Investigational Treatments. Other treatments for

depres-sion are being tested. These include transcranial magnetic stimulation

(TMS), magnetic seizure therapy, deep brain stimulation, and vagal nerve

stimulation. TMS is the closest to approval for clinical use. These novel

brain-stimulation techniques seem to be safe, but their efficacy in relieving

depression needs to be established (Eitan & Lerer, 2006).

Related Topics