Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Mood Disorders

Application of the Nursing Process: Bipolar Disorder

APPLICATION OF THE NURSING

PROCESS: BIPOLAR DISORDER

The focus of this discussion is on the client experiencing a manic

episode of bipolar disorder. The reader should review the Application of the

Nursing Process: Depression section to examine nursing care of the client

experiencing a depressed phase of bipolar disorder.

Assessment

History

Taking a history with a client in the manic phase often proves

difficult. The client may jump from subject to sub-ject, which makes it

difficult for the nurse to follow. Obtaining data in several short sessions, as

well as talking to family members, may be necessary. The nurse can obtain much

information, however, by watching and listening.

General Appearance and Motor Behavior

Clients with mania experience psychomotor agitation and seem to be

in perpetual motion; sitting still is difficult. This continual movement has

many ramifications: clients can become exhausted or injure themselves.

In the manic phase, the client may wear clothes that reflect the

elevated mood: brightly colored, flamboyant, attention-getting, and perhaps

sexually suggestive. For example, a woman in the manic phase may wear a lot of

jewelry and hair ornaments, or her makeup may be garish and heavy, whereas a

male client may wear a tight and revealing muscle shirt or go bare-chested.

Clients experiencing a manic episode think, move, and talk fast.

Pressured speech, one of the hallmark symptoms, is evidenced by unrelentingly

rapid and often loud speech with-out pauses. Those with pressured speech

interrupt and cannot listen to others. They ignore verbal and nonverbal cues

indi-cating that others wish to speak, and they continue with con-stant

intelligible or unintelligible speech, turning from one listener to another or

speaking to no one at all. If interrupted, clients with mania often start over

from the beginning.

Mood and Affect

Mania is reflected in periods of euphoria, exuberant activ-ity,

grandiosity, and false sense of well-being. Projection of an all-knowing and

all-powerful image may be an uncon-scious defense against underlying low

self-esteem. Some clients manifest mania with an angry, verbally aggressive

tone and are sarcastic and irritable, especially when others set limits on

their behavior. Clients’ mood is quite labile, and they may alternate between

periods of loud laughter and episodes of tears.

Thought Process and Content

Cognitive ability or thinking is confused and jumbled with thoughts

racing one after another, which is often referred to as flight of ideas.

Clients cannot connect concepts, and they jump from one subject to another.

Circumstantiality and tangentiality also characterize thinking. At times,

cli-ents may be unable to communicate thoughts or needs in ways that others

understand.

These clients start many projects at one time but cannot carry any

to completion. There is little true planning, but clients talk nonstop about

plans and projects to anyone and everyone, insisting on the importance of

accomplishing these activities. Sometimes they try to enlist help from oth-ers

in one or more activities. They do not consider risks or personal experience,

abilities, or resources. Clients start these activities as they occur in their

thought processes. Examples of these multiple activities are going on shopping

sprees, using credit cards excessively while unemployed and broke, starting

several business ventures at once, hav-ing promiscuous sex, gambling, taking

impulsive trips, embarking on illegal endeavors, making risky investments,

talking with multiple people, and speeding (APA, 2000).

Some clients experience psychotic features during mania; they

express grandiose delusions involving importance, fame, privilege, and wealth.

Some may claim to be the presi-dent, a famous movie star, or even God or a

prophet.

Sensorium and Intellectual Processes

Clients may be oriented to person and place but rarely to time.

Intellectual functioning, such as fund of knowledge, is difficult to assess

during the manic phase. Clients may claim to have many abilities they do not

possess. The abil-ity to concentrate or to pay attention is grossly impaired.

Again, if a client is psychotic, he or she may experience hallucinations.

Judgment and Insight

People in the manic phase are easily angered and irritated and

strike back at what they perceive as censorship by oth-ers because they impose

no restrictions on themselves. They are impulsive and rarely think before

acting or speak-ing, which makes their judgment poor. Insight is limited

because they believe they are “fine” and have no problems. They blame any

difficulties on others.

Self-Concept

Clients with mania often have exaggerated self-esteem; they believe

they can accomplish anything. They rarely discuss their self-concept

realistically. Nevertheless, a false sense of well-being masks difficulties

with chronic low self-esteem.

Roles and Relationships

Clients in the manic phase rarely can fulfill role

responsi-bilities. They have trouble at work or school (if they are even

attending) and are too distracted and hyperactive to pay attention to children

or activities of daily living. Although they may begin many tasks or projects,

they complete few.

These clients have a great need to socialize but little

understanding of their excessive, overpowering, and confrontational social

interactions. Their need for social-ization often leads to promiscuity. Clients

invade the intimate space and personal business of others. Argu-ments result

when others feel threatened by such bound-ary invasions. Although the usual

mood of manic people is elation, emotions are unstable and can fluctuate (labile emotions) readily between euphoria and hostility. Cli-ents with

mania can become hostile to others whom they perceive as standing in way of

desired goals. They can-not postpone or delay gratification. For example, a

manic client tells his wife, “You are the most wonderful woman in the world.

Give me $50 so I can buy you a ticket to the opera.” When she refuses, he

snarls and accuses her of being cheap and selfish and may even strike her.

Physiologic and Self-Care Considerations

Clients with mania can go days without sleep or food and not even

realize they are hungry or tired. They may be on the brink of physical

exhaustion but are unwilling or unable to stop, rest, or sleep. They often

ignore personal hygiene as “boring” when they have “more important things” to

do. Clients may throw away possessions or destroy valued items. They may even

physically injure themselves and tend to ignore or be unaware of health needs

that can worsen.

Data Analysis

The nurse analyzes assessment data to determine priorities and to

establish a plan of care. Nursing diagnoses com-monly established for clients

in the manic phase are as follows:

The client will participate

in self-care activities.

·

The client will evaluate personal qualities realistically.

·

The client will engage in socially appropriate, reality-based

interaction.

·

The client will verbalize knowledge of his or her illness and

treatment.

Intervention

Providing for Safety

Because of the safety risks that clients in the manic phase take,

safety plays a primary role in care, followed by issues related to self-esteem

and socialization. A primary nursing responsibility is to provide a safe

environment for clients and others. The nurse assesses clients directly for

suicidal ideation and plans or thoughts of hurting others. In addi-tion,

clients in the manic phase have little insight into their anger and agitation

and how their behaviors affect others. They often intrude into others’ space,

take others’ belongings without permission, or appear aggressive in approaching

others. This behavior can threaten or anger people who then retaliate. It is

important to monitor the clients’ whereabouts and behaviors frequently.

The nurse also should tell clients that staff members will help

them control their behavior if clients cannot do so alone. For clients who feel

out of control, the nurse must establish external controls empathetically and

nonjudg-mentally. These external controls provide long-term com-fort to

clients, although their initial response may be aggression. People in the manic

phase have labile emotions; it is not unusual for them to strike staff members

who have set limits in a way clients dislike.

These clients physically and psychologically invade boundaries. It

is necessary to set limits when they cannot set limits on themselves. For

example, the nurse might say,

Risk for Other-Directed Violence

·

Risk for Injury

·

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements

·

Ineffective Coping

·

Noncompliance

·

Ineffective Role Performance

·

Self-Care Deficit

·

Chronic Low Self-Esteem

·

Disturbed Sleep Pattern

Outcome Identification

Examples of outcomes appropriate to mania are as follows:

·

The client will not injure self or others.

·

The client will establish a balance of rest, sleep, and activity.

The client will establish adequate nutrition, hydration, and

elimination.

·

The client will participate in self-care activities.

·

The client will evaluate personal qualities realistically.

·

The client will engage in socially appropriate, reality-based

interaction.

·

The client will verbalize knowledge of his or her illness and

treatment.

Intervention

Providing for Safety

Because of the safety risks that clients in the manic phase take,

safety plays a primary role in care, followed by issues related to self-esteem

and socialization. A primary nursing responsibility is to provide a safe

environment for clients and others. The nurse assesses clients directly for

suicidal ideation and plans or thoughts of hurting others. In addi-tion,

clients in the manic phase have little insight into their anger and agitation

and how their behaviors affect others. They often intrude into others’ space,

take others’ belongings without permission, or appear aggressive in approaching

others. This behavior can threaten or anger people who then retaliate. It is

important to monitor the clients’ whereabouts and behaviors frequently.

The nurse also should tell clients that staff members will help

them control their behavior if clients cannot do so alone. For clients who feel

out of control, the nurse must establish external controls empathetically and

nonjudg-mentally. These external controls provide long-term com-fort to

clients, although their initial response may be aggression. People in the manic

phase have labile emotions; it is not unusual for them to strike staff members

who have set limits in a way clients dislike.

These clients physically and psychologically invade boundaries. It

is necessary to set limits when they cannot set limits on themselves. For

example, the nurse might say,

![]()

![]() “John, you are too close to my face. Please stand back 2 feet.”

“John, you are too close to my face. Please stand back 2 feet.”

or

“It is unacceptable to hug other clients. You may talk to others, but do not touch them.”

When setting limits, it is important to clearly identify the

unacceptable behavior and the expected, appropriate behavior. All staff must

consistently set and enforce limits for those limits to be effective.

Meeting Physiologic Needs

Clients with mania may get very little rest or sleep, even if they

are on the brink of physical exhaustion. Medication may be helpful, though

clients may resist taking it. Decreas-ing environmental stimulation may assist

clients to relax. The nurse provides a quiet environment without noise,

television, or other distractions. Establishing a bedtime routine, such as a

tepid bath, may help clients to calm down enough to rest.

Nutrition is another area of concern. Manic clients may be too

“busy” to sit down and eat, or they may have such poor concentration that they

fail to stay interested in food for very long. “Finger foods” or things clients

can eat while moving around are the best options to improve nutrition. Such

foods also should be as high in calories and protein as possible. For example,

celery and carrots are finger foods, but they supply little nutrition.

Sandwiches, protein bars, and fortified shakes are better choices. Clients with

mania also benefit from food that is easy to eat without much preparation. Meat

that must be cut into bite sizes or plates of spaghetti are not likely to be

successful options. Having snacks available between meals, so clients can eat

whenever possible, is also useful.

The nurse needs to monitor food and fluid intake and hours of sleep

until clients routinely meet these needs without difficulty. Observing and

supervising clients at meal times are also important to prevent clients from

tak-ing food from others.

Providing Therapeutic Communication

Clients with mania have short attention spans, so the nurse uses

clear, simple sentences when communicating. They may not be able to handle a

lot of information at once, so the nurse breaks information into many small

segments. It helps to ask clients to repeat brief messages to ensure they have

heard and incorporated them.

Clients may need to undergo baseline and follow-up laboratory

tests. A brief explanation of the purpose of each test allays anxiety. The

nurse gives printed information to reinforce verbal messages, especially those

related to rules, sched-ules, civil rights, treatment, staff names, and client

education.

The speech of manic clients may be pressured: rapid,

circumstantial, rhyming, noisy, or intrusive with flights of ideas. Such

disordered speech indicates thought pro-cesses that are flooded with thoughts,

ideas, and impulses. The nurse must keep channels of communica-tion open with

clients, regardless of speech patterns. The nurse can say,

“Please speak more

slowly. I’m having trouble following you.”

This puts the responsibility for the communication dif-ficulty on

the nurse rather than on the client. This nurse patiently and frequently

repeats this request during con-versation because clients will return to rapid

speech.

Clients in the manic phase often use pronouns when referring to

people, making it difficult for listeners to understand who is being discussed

and when the conver-sation has moved to a new subject. While clients are

agi-tatedly talking, they usually are thinking and moving just as quickly, so

it is a challenge for the nurse to follow a coherent story. The nurse can ask

clients to identify each person, place, or thing being discussed.

When speech includes flight of ideas, the nurse can ask clients to

explain the relationship between topics—for example,

“What happened

then?”

or

“Was that

before or after you got married?”

The nurse also assesses and documents the coherence of messages.

Clients with pressured speech rarely let others speak. Instead,

they talk nonstop until they run out of steam or just stand there looking at

the other person before moving away. Those with pressured speech do not respond

to oth-ers’ verbal or nonverbal signals that indicate a desire to speak. The

nurse avoids becoming involved in power struggles over who will dominate the

conversation. Instead, the nurse may talk to clients away from others so there

is no “competition” for the nurse’s attention. The nurse also sets limits

regarding taking turns speaking and listening as well as giving attention to

others when they need it. Clients with mania cannot have all requests granted

immediately even though that may be their desire.

Promoting Appropriate Behaviors

These clients need to be protected from their pursuit of socially

unacceptable and risky behaviors. The nurse can direct their need for movement

into socially acceptable, large motor activi-ties such as arranging chairs for

a community meeting or walk-ing. In acute mania, clients lose the ability to

control their behavior and engage in risky activities. Because acutely manic

clients feel extraordinarily powerful, they place few restrictions on

themselves. They act out impulsive thoughts, have inflated and grandiose

perceptions of their abilities, are demanding, and need immediate

gratification. This can affect their physi-cal, social, occupational, or

financial safety as well as that of others. Clients may make purchases that

exceed their ability to pay. They may give away money or jewelry or other

posses-sions. The nurse may need to monitor a client’s access to such items

until his or her behavior is less impulsive.

In an acute manic episode, clients also may lose sexual

inhibitions, resulting in provocative and risky behaviors. Clothing may be

flashy or revealing, or clients may undress in public areas. They may engage in

unprotected sex with virtual strangers. Clients may ask staff members or other

clients (of the same or opposite sex) for sex, graphically describe sexual

acts, or display their genitals. The nurse handles such behav-ior in a

matter-of-fact, nonjudgmental manner. For example,

“Mary, let’s go

to your room and find a sweater.”

It is important to treat clients with dignity and respect despite

their inappropriate behavior. It is not helpful to “scold” or chastise them;

they are not children engaging in willful misbehavior.

In the manic phase, clients cannot understand personal boundaries,

so it is the staff’s role to keep clients in view for intervention as

necessary. For example, a staff member who sees a client invading the intimate

space of others can say,

“Jeffrey, I’d

appreciate your help in setting up a circle of chairs in the group therapy

room.”

This large motor activity distracts Jeffrey from his inap-propriate

behavior, appeals to his need for heightened physical activity, is

noncompetitive, and is socially accept-able. The staff’s vigilant redirection

to a more socially appropriate activity protects clients from the hazards of

unprotected sex and reduces embarrassment over such behaviors when they return

to normal behavior.

Managing Medications

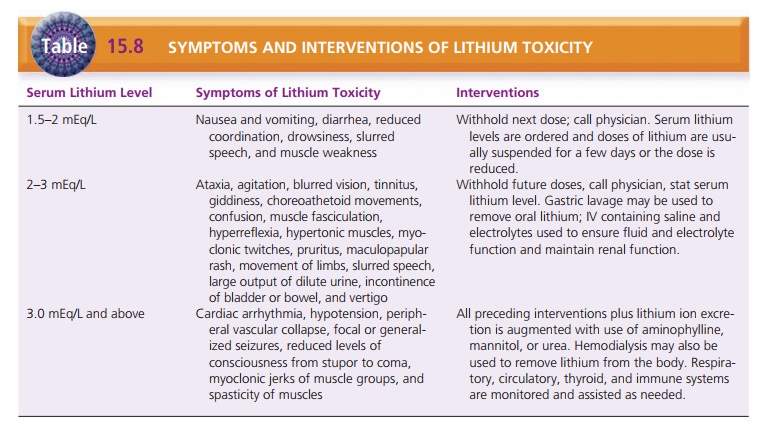

Lithium is not metabolized; rather, it is reabsorbed by the

proximal tubule and excreted in the urine. Periodic serum lithium levels are

used to monitor the client’s safety and to ensure that the dose given has

increased the serum lithium level to a treatment level or reduced it to a

maintenance level. There is a narrow range of safety among maintenance levels

(0.5 to 1 mEq/L), treatment levels (0.8 to 1.5 mEq/L), and toxic levels (1.5

mEq/L and above). It is important to assess for signs of toxicity and to ensure

that clients and their fami-lies have this information before discharge (Table

15.8).

![]()

![]() Older adults can have symptoms of toxicity at

lower serum levels. Lithium is potentially fatal in overdose.

Older adults can have symptoms of toxicity at

lower serum levels. Lithium is potentially fatal in overdose.

Clients should drink adequate water (approximately 2 L/day) and

continue with the usual amount of dietary table salt. Having too much salt in

the diet because of unusually salty foods or the ingestion of salt-containing

antacids can reduce receptor availability for lithium and increase lithium

excretion, so the lithium level will be too low. If there is too much water,

lithium is diluted and the lithium level will be too low to be therapeutic.

Drink-ing too little water or losing fluid through excessive sweating,

vomiting, or diarrhea increases the lithium level, which may result in

toxicity. Monitoring daily weights and the balance between intake and output

and checking for dependent edema can be helpful in moni-toring fluid balance.

The physician should be contacted if the client has diarrhea, fever, flu, or

any condition that leads to dehydration.

Thyroid function tests usually are ordered as a base-line and every

6 months during treatment with lithium. In 6 to 18 months, one third of clients

taking lithium have an increased level of thyroid-stimulating hormone, which

can cause anxiety, labile emotions, and sleeping difficulties. Decreased levels

are implicated in fatigue and depression.

Because most lithium is excreted in the urine, baseline and

periodic assessments of renal status are necessary to assess renal function.

The reduced renal function in older adults necessitates lower doses. Lithium is

contraindicated in people with compromised renal function or urinary retention

and those taking low-salt diets or diuretics. Lith-ium also is contraindicated

in people with brain or cardio-vascular damage.

Providing Client and Family Teaching

Educating clients about the dangers of risky behavior is necessary;

however, clients with acute mania largely fail to heed such teaching because

they have little patience or capacity to listen, understand, and see the

relevance of this information. Clients with euphoria may not see why the

behavior is a problem because they believe they can do anything without

impunity. As they begin to cycle toward normalcy, however, risky behavior

lessens, and they become ready and able for teaching.

Manic clients start many tasks, create many goals, and try to carry

them out all at once. The result is that they cannot complete any. They move

readily between these goals while sometimes obsessing about the importance of

one over another, but the goals can quickly change. Cli-ents may invest in a business

in which they have no knowledge or experience, go on spending sprees,

impul-sively travel, speed, make new “best friends,” and take the center of

attention in any group. They are egocentric and have little concern for others

except as listeners, sex-ual partners, or the means to achieve one of their

poorly conceived goals.

Education about the cause of bipolar disorder, medi-cation

management, ways to deal with behaviors, and potential problems that manic

people can encounter is important for family members. Education reduces the

guilt, blame, and shame that accompany mental illness; increases client safety;

enlarges the support system for clients and the family members; and promotes

compli-ance. Education takes the “mystery” out of treatment for mental illness

by providing a proactive view: this is what we know, this is what can be done,

and this is what you can do to help.

Family members often say they know clients have stopped taking

their medication when, for example, cli-ents become more argumentative, talk

about buying expensive items that they cannot afford, hotly deny any-thing is

wrong, or demonstrate any other signs of escalat-ing mania. People sometimes

need permission to act on their observations, so a family education session is

an appropriate place to give this permission and to set up interventions for

various behaviors.

Clients should learn to adhere to the established dos-age of

lithium and not to omit doses or change dosage intervals; unprescribed dosage

alterations interfere with maintenance of serum lithium levels. Clients should

know about the many drugs that interact with lithium and should tell each

physician they consult that they are taking lithium. When a client taking

lithium seems to have increased manic behavior, lithium levels should be

checked to determine whether there is lithium toxic-ity. Periodic monitoring of

serum lithium levels is nec-essary to ensure the safety and adequacy of the

treat-ment regimen. Persistent thirst and diluted urine can indicate the need

to call a physician and have the serum lithium level checked to see if the

dosage needs to be reduced.

Evaluation

Evaluation of the treatment of bipolar disorder includes but is not

limited to the following:

·

Safety issues

·

Comparison of mood and affect between start of treat-ment and

present

·

Adherence to treatment regimen of medication and psychotherapy

·

Changes in client’s perception of quality of life

Achievement of specific goals of treatment including new coping

methods

Related Topics