Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Postpartum Hemorrhage

Major Causes of Postpartum Hemorrhage and their Management

MAJOR CAUSES OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE AND THEIR MANAGEMENT

Uterine Atony

Ordinarily, the uterine corpus

contracts promptly after delivery of the placenta, constricting the spiral

arteries in the newly created placental bed, and preventing excessive bleeding.

This muscular contraction, rather than coagu-lation, prevents excessive

bleeding from the placental implantation site. When contraction does not occur

as expected, the resulting uterine atony

leads to PPH.

Conditions that predispose to

uterine atony include those in which there is extraordinary enlargement of the

uterus (such as polyhydramnios or twins); abnormal labor (both precipitous and prolonged,

or augmented by oxy-tocin); and conditions that interfere with contraction of

the uterus (such as uterine leiomyomata or magnesium sulfate). The clinical

diagnosis of atony is based largely on the tone of the uterine muscle on

palpation. Instead of the normally firm, contracted uterine corpus, a softer,

more pliable— often called “boggy”—uterus is found. The cervix is usu-ally

open. Frequently, the uterus contracts briefly when massaged, only to become

relaxed again when the manipu-lation ceases.

Because

hemorrhage can occur in the absence of atony, other etiologies must be sought

in the presence of a firm fundus.

Management of uterine atony is

both preventive and therapeutic. Active

management of the third stage of labor (theinterval between the delivery of the

fetus and delivery of the pla-centa), has been shown to reduce the incidence of

PPH hemor-rhage by as much as 70%. The protocol for management ofthe third

stage includes oxytocin infusion (usually 20 units in 1 liter of normal saline

infused at 200–500 mL/hr) initi-ated immediately following delivery of the

infant or its ante-rior shoulder, gentle cord traction, and uterine massage.

Some physicians do not begin oxytocin infusion until after delivery of the

placenta to avoid placental entrapment. However, there is no firm evidence that

the rates of entrap-ment are higher with active management than with other

strategies. Immediate breastfeeding may also enhance uterine contractility and,

thus, reduce blood loss.

Once uterine atony is diagnosed,

management can be categorized as medical, manipulative, or surgical.

Manage-ment must be individualized in cases of severe uterine atony, taking

into account the extent of hemorrhage, the overall status of the patient, and

her future childbearing desires (see Box 12.2).

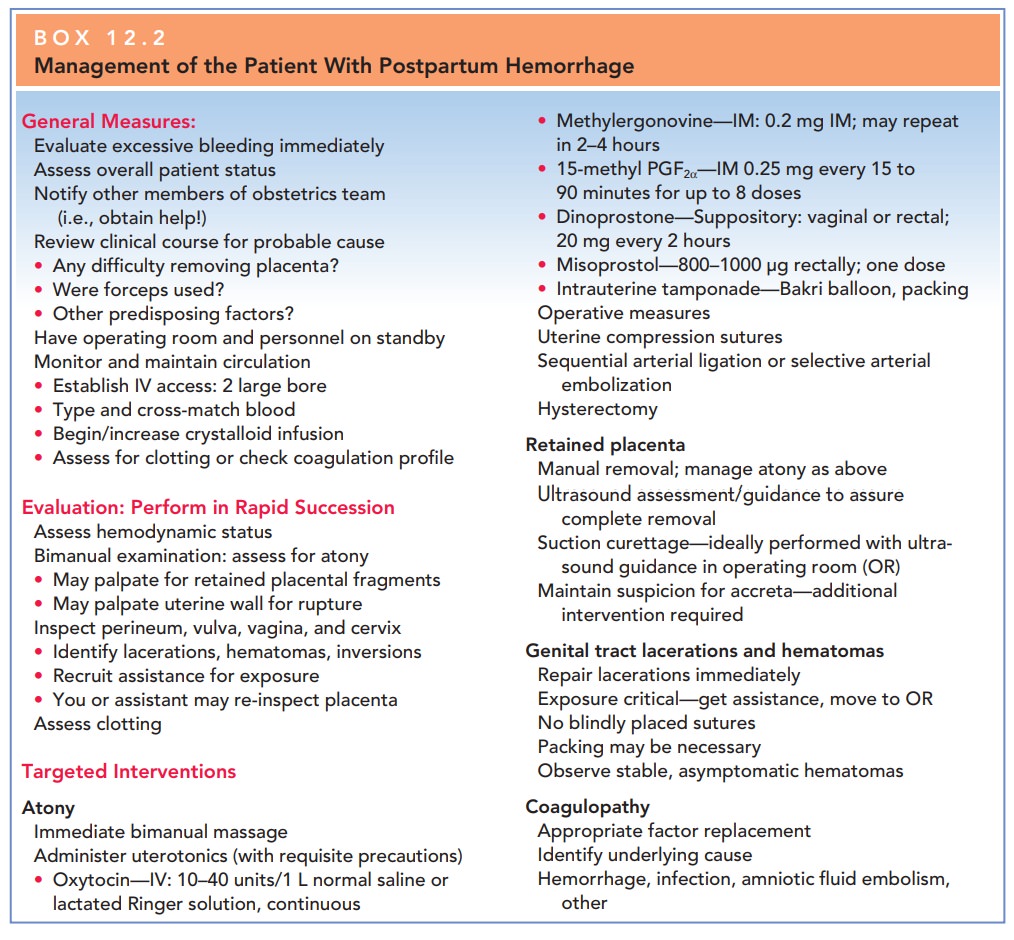

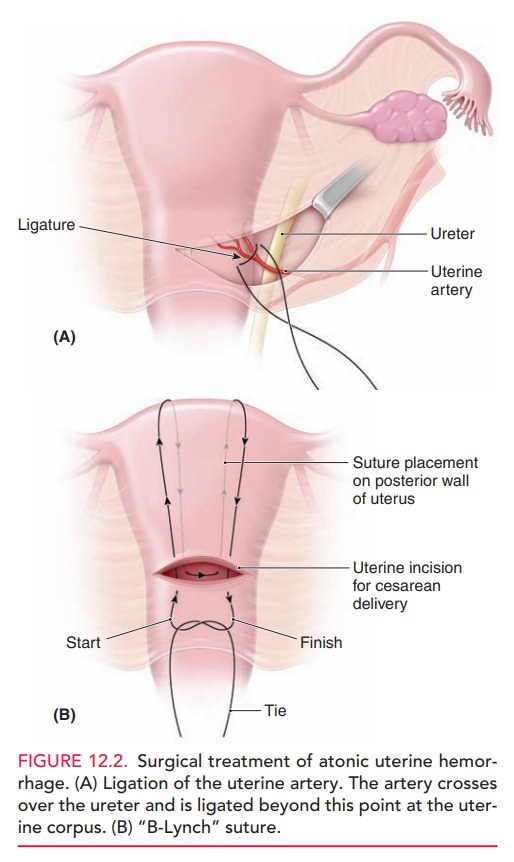

Bimanual uterine massage alone is often successful in caus-ing uterine contraction, and this should be done while preparations for other treatments are under way (Fig. 12.1).Uterotonicagents include oxytocin, methylergonovine maleate, miso-prostol (an analogue of prostaglandin E1), dinoprostone (an analogue of prostaglandin E2), and 15-methyl prostaglandin F2α, administered separately or in combination. Methyl-ergonovine maleate is a potent uterotonic agent that cancause uterine contractions within several minutes. It is always given intramuscularly, because rapid intravenous administration can lead to dangerous hypertension, and its use is often avoided in those with hypertensive disorders.

Though it should be avoided or used with extreme caution in those with cardiac, pulmonary,

liver, or renal diseases, 15-methyl

prostaglandin F2may be given intramuscu-larly or directly into

the myometrium. Dinoprostone may be

given by vaginal or rectal suppository. Misoprostol

has recently been used for treatment and prevention of PPH. These

prostaglandins result in strong uterine contractions. Typically, oxytocin is

given prophylactically, as noted previously; if uterine atony occurs, the

infusion rate is increased, and additional agents are given sequentially.

Uterotonic

agents are only effective for uterine atony. If the uterus is firm, the use of

these agents is not necessary and other causes of bleeding should be explored.

Occasionally, uterine massage and

uterotonic agents are unsuccessful in bringing about adequate uterine

con-traction, and other measures must be used. Some practi-tioners use

intrauterine compression with in utero packing or placement of a balloon

compression device as a means of halting blood loss while preserving the

uterus.

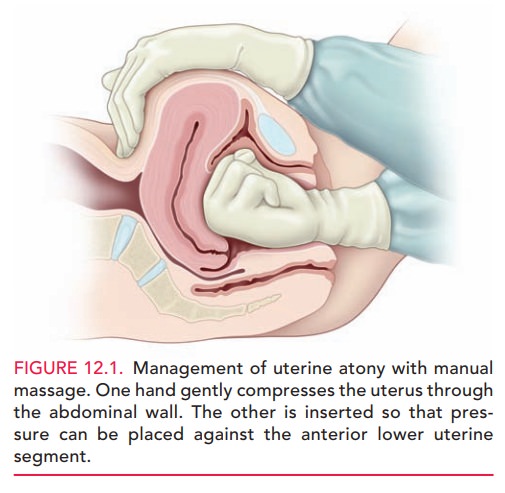

Surgical

management of uterine atony may includeuterine compression

sutures (B-Lynch or multiple squares), sequential arterial ligation (ascending

or descending branches of the uterine, utero-ovarian, then internal iliac

arteries), selective arterial embolization, and hysterectomy (Fig. 12.2). Very high success rates have been noted with

surgi-cal compression techniques, with consequent decreases in the use of

hysterectomy and iliac artery ligations, both of which are asso-ciated with

high rates of morbidity. Additional advantages ofcompression techniques

include rapid execution and preservation of fertility.

Lacerations of the Lower Genital Tract

Lacerations

of the lower genital tract are far less commonthan

uterine atony as a cause of PPH, but they can be seri-ous and require prompt

surgical repair. Predisposing

factorsinclude instrumented delivery, manipulative delivery such as a breech

extraction, precipitous labor, presentations other than occiput anterior, and

macrosomia.

Although minor lacerations to the

cervix are common in delivery, extensive lacerations and those that are

actively bleeding usually require repair. To minimize blood loss caused by

significant cervical and vaginal lacerations, all patients with any

predisposing factors, or any patient in whom blood loss soon after delivery

appears to be exces-sive despite a firm and contracted uterus, should have a

careful repeat inspection of the lower genital tract. This vaginal examination

may require assistance to allow ade-quate visualization. As a rule, repair of

these lacerations is usually not difficult, if adequate exposure is provided.

Lacerations of the vagina and perineum (first-degree through fourth-degree vaginal and periurethral lacera-tions) are not common causes of substantial blood loss, although the steady loss of blood, which may come from deeper lacerations, may be so significant that their repair when bleeding is requisite.

Periurethral

lacerations may be associated with sufficient edema to occlude the urethra,

causing urinary retention; a Foley catheter for 12 to 24 hours usually

alleviates this problem.

Retained Placenta

Normally, separation of the

placenta from the uterus occurs because of cleavage between the zona basalis and the zonaspongiosa facilitated by uterine

contraction. Once separa-tion occurs, expulsion is caused by strong uterine

contrac-tions. Retained placenta can

occur when either the process of separation or the process of expulsion is

incomplete. Predisposing factors to retained placenta include a previous

cesarean delivery, uterine leiomyomata, prior uterine curet-tage, and

succenturiate placental lobe.

Placental tissue remaining in the

uterus can prevent adequate contractions, leading to atony and excessive

bleeding.

After

expulsion, every placenta should be inspected to detect missing placental

cotyledons, which may remain in the uterus.

Sheared or abruptly ending

surface vessels may indicate an accessory, or succenturiate, placental lobe. If retained placenta is

suspected—either because of apparently absent cotyledons or because of

excessive bleeding—it can often be removed by inserting two fingers through the

cervix into the uterine cavity, and manipulating the retained tis-sue downward

into the vagina. If this is unsuccessful, or if there is uncertainty regarding

the cause of hemorrhage, an ultrasound examination of the uterus can be helpful.

Curettage with a suction apparatus and/or a large, sharp curette may be used to

remove the retained tissue. Care must be exercised to avoid perforation through

the uterine fundus.

Placental tissue may also remain

in the uterus because separation of the placenta from the uterus may not occur

normally. At times, placental villi penetrate the uterine wall to varying

degrees. Specifically, abnormal adherence of the placenta to the superficial

lining of the uterus is termed pla-centa

accreta; penetration into the uterine muscle itselfis called placenta increta; and complete invasion

through the thickness of the uterine muscle is termed placentapercreta. If this abnormal attachment involves the

entireplacenta, no part of the placenta separates. Much more commonly, however,

attachment is not complete and a por-tion of the placenta separates and the

remainder remains attached. Major, life-threatening hemorrhage can ensue.

If a portion of the placenta separates and the remainder stays attached, hysterectomy is often required. However, an attempt to separate the placenta by curettage or other means of controlling the bleeding (such as surgical compres-sion or sequential arterial ligation) is usually appropriate in trying to avoid a hysterectomy in a woman who desires more children.

Other Causes of Postpartum Hemorrhage

HEMATOMAS

Hematomas

can occur anywhere from the vulva to theupper

vagina as a result of delivery trauma. Hematomas may also develop at the site

of episiotomy or perineal lac-eration. Hematomas may occur without disruption

of the vaginal mucosa, when the fetus or forceps causes shearing of the

submucosal tissues without mucosal tearing.

Vulvar or vaginal hematomas are

characterized by exquisite pain with or without signs of shock. Hematomasthat are ≤5 cm in

diameter and are not enlarging can usually be managed expectantly by frequent

evaluation of the size of the hematoma and close monitoring of vital signs and

urinary out-put. Application of ice packs can also

be helpful. Largerand enlarging hematomas must be managed surgically. If the

hematoma is at the site of episiotomy, the sutures should be removed and a

search made for the actual bleed-ing site, which is then ligated. If it is not

at the episiotomy site, the hematoma should be opened at its most depen-dent

portion and drained, the bleeding site identified, if possible, and the site

closed with interlocking hemostatic sutures. Drains and vaginal packs are often

used to prevent reaccumulation of blood. It should be noted that large amounts

of blood can dissect and accumulate along tissue planes, especially into the

ischiorectal fossa, precluding easy identification. This may be seen in those

with trauma involving the vaginal side walls and sulci. Thus, careful

monitoring of hemodynamic status is important in identi-fying those with occult

bleeding.

COAGULATION DEFECTS

Virtually any congenital or

acquired abnormality in blood clotting can lead to PPH. Abruptio placentae,

amniotic fluid embolism, sepsis, and severe preeclampsia are obstet-ric

conditions associated with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. The

treatment of coagulation disorders

involves correction of the coagulation defect with appro-priate factor

replacement.

When

assessing a patient with PPH, a specimen of the blood that is passing from the

genital tract should be obtained in a plain test tube to check whether the

blood is clotting.

It also should be recalled that

profuse hemorrhage itself can lead to coagulopathy, thus creating a vicious

cycle of bleeding.

AMNIOTIC FLUID EMBOLISM

Amniotic

fluid embolism is a rare, sudden, and oftenfatal obstetric

complication thought to be caused primar-ily by entry of amniotic fluid into

the maternal circulation. Significant biochemical, as well as physical,

mediators are thought to be involved in the development of the clinical

scenario, which unfolds as five findings that occur in sequence: (1)

respiratory distress, (2) cyanosis, (3) cardio-vascular collapse, (4)

hemorrhage, and (5) coma. The syn-drome

also often results in severe coagulopathy. Treatmentis directed toward

total support of the cardiovascular and coagulation systems, although maternal

mortality still approaches 30% to 50% in most series.

UTERINE INVERSION

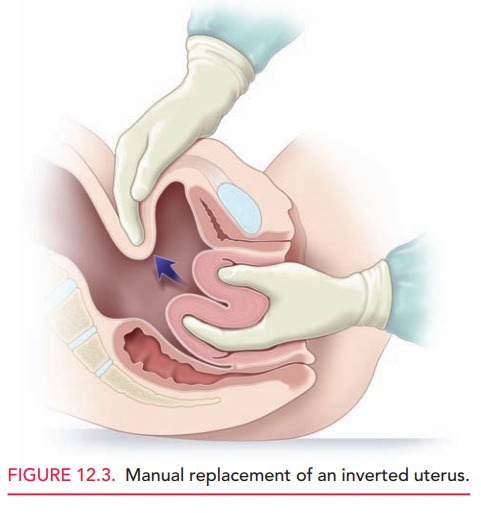

Uterine inversion is a rare condition in which the uterusliterally turns inside out, with the top of the uterine fun-dus extending through the cervix into the vagina and some-times even past the introitus (Fig. 12.3). Hemorrhage with uterine inversion is characteristically severe and sudden. Treatment includes manual replacement, which frequently requires administration of an agent that causes uterine relaxation (such as terbutaline, magnesium sulfate, halo-genated general anesthetics, and nitroglycerin). If manual replacement fails, surgery is required.

UTERINE RUPTURE

Uterine rupture should be

distinguished from dehiscence of a low transverse incision, as the clinical

connotations are quite different. A uterine

rupture is a frank opening between the uterine cavity and the abdominal

cavity. A uterine dehiscence is a

“window” covered by the vis-ceral peritoneum. Significantly higher rates of

maternal and fetal morbidity, and even maternal mortality, occur in cases of

overt rupture.

Rupture can occur at the site of a previous cesarean delivery or other surgical procedure involving the uterine wall—from intrauterine manipulation or trauma, or from congenital malformation (small uterine horn), or sponta-neously. Abnormal labor, operative delivery, and placenta accreta can lead to rupture. Surgical repair is required, with the specific approach tailored to reconstruct the uterus, if possible. Care depends on the extent and site of rupture, the patient’s current clinical condition, and her desire for future childbearing. Rupture of a previous cesarean delivery scar often can be managed by revision of the edges of the prior incision, followed by primary closure. In addition to the myometrial disruption, consideration must be given to the neighboring structures, such as the broad ligament, para-metrial vessels, ureters, and bladder.

Regardless of

the patient’s wishes for the avoidance of hysterectomy, this pro-cedure may be

necessary in a life-threatening situation. Careful

assessment in the face of maternal hemodynamic changes and monitoring other

signs, such as acute abdominal pain, change in abdominal contour,

non-reassuring fetal heart patterns, and loss of fetal station, are critical in

early detection and interven-tion in such cases.

Related Topics