Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Hepatic Physiology & Anesthesia

Liver Tests

LIVER TESTS

The most commonly performed liver tests are nei-ther sensitive nor

specific. No one test evaluates overall hepatic function, reflecting instead

one aspect of hepatic function that must be interpreted in conjunction with

other tests and clinical assess-ment of the patient.

Many “liver function” tests, such as serum

transaminase measurements, reflect hepato-

cellular integrity more than hepatic

function. Liver tests that measure hepatic synthetic function include

serum albumin, prothrombin time (PT, or inter-national normalized ratio

[INR]), cholesterol, and pseudocholinesterase. Moreover, because of the liver’s

large functional reserve, substantial cirrhosis may be present with few or no

laboratory abnormalities.

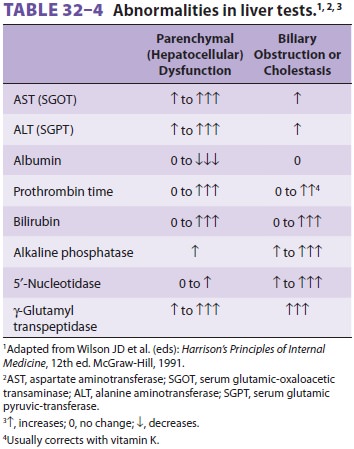

Liver abnormalities can often be divided into either parenchymal

disorders or obstructive dis-orders based on laboratory tests (Table 32–4). Obstructive disorders

primarily affect biliary excre-tion of substances, whereas parenchymal

disorders result in generalized hepatocellular dysfunction.

Serum Bilirubin

The normal total bilirubin concentration,

composed of conjugated (direct), water-soluble and uncon-jugated (indirect),

lipid-soluble forms, is less than 1.5 mg/dL (<25 mmol/L) and reflects the balance between

bilirubin production and excretion. Jaundice is usually clinically obvious when

total bilirubin exceeds 3 mg/dL. A predominantly conjugated hyper-bilirubinemia

(>50%) is associated with

increased urinary urobilinogen and may reflect hepatocellular dysfunction,

congenital (Dubin–Johnson or Rotor syndrome) or acquired intrahepatic

cholestasis, or extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Hyperbilirubinemia that is

primarily unconjugated may be seen with hemolysis or with congenital (Gilbert

or Crigler– Najjar syndrome) or acquired defects in bilirubin conjugation.

Unconjugated bilirubin is neurotoxic, and high levels may produce

encephalopathy.

Serum Aminotransferases (Transaminases)

These enzymes are released into the circulation as a result of

hepatocellular injury or death. Two aminotransferases are most commonly

measured: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), also known as serum

glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT),

also known as serum glutamic pyruvic-transferase (SGPT).

Serum Alkaline Phosphatase

Alkaline phosphatase is produced by the

liver, bone, small bowel, kidneys, and placenta and is excreted into bile.

Normal serum alkaline phosphatase activ-ity is generally 25–85 IU/L; children

and adolescents have much higher levels, reflecting active growth. Most of the

circulating enzyme is normally derived from bone; however, with biliary

obstruction, more hepatic alkaline phosphatase is synthesized and released into

the circulation.

Serum Albumin

The normal serum albumin

concentration is 3.5– 5.5 g/dL. Because its half-life is about 2–3 weeks,

albumin concentration may initially be normalwith

acute liver disease. Albumin values less than 2.5 g/dL are generally indicative

ofchronic liver disease, acute stress, or severe

malnu-trition. Increased losses of albumin in the urine (nephrotic syndrome) or

the gastrointestinal tract (protein-losing enteropathy) can also produce

hypoalbuminemia.

Blood Ammonia

Significant elevations of blood ammonia levels usually reflect

disruption of hepatic urea syn-thesis. Normal whole blood ammonia levels are

47–65 mmol/L (80–110 mg/dL). Marked elevations usually reflect severe

hepatocellular damage and may cause encephalopathy.

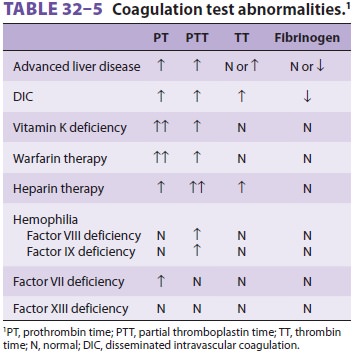

Prothrombin Time

The PT, which normally ranges between 11–14

sec, depending on the control value,measures the activity of fibrinogen,

prothrom-bin, and factors V, VII, and X. The relatively short half-life of

factor VII (4–6 h) makes the PT useful in evaluating hepatic synthetic function

of patients with acute or chronic liver disease. Prolongations of the PT

greater than 3–4 sec from the control are considered significant and usually

correspond to an INR 1.5. Because only 20% to 30% of normal factor activity is

required for normal coagulation, prolon-gation of the PT usually reflects

either severe liver disease or vitamin K deficiency. (See Table 32–5 for a list

of coagulation test abnormalities.)

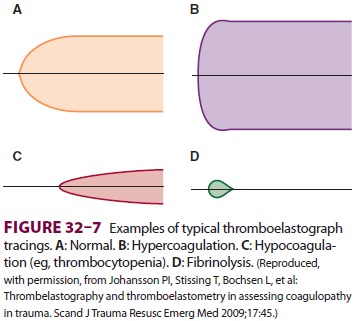

Point-of-Care Viscoelastic Coagulation Monitoring

This technology provides a “real time”

assessment of the coagulation status and utilizes thromboelas-tography (TEG ®), rotation

thromboelastometry (ROTEM®), or Sonoclot® analysis to assess global coagulation via the viscoelastic properties

of whole blood (Figure 32–7). A clear picture is

provided of the global effect of imbalances between the proco-agulant and

anticoagulant systems and the profibri-nolytic and antifibrinolytic systems and

the resultant

clot tensile strength, allowing precise management of hemostatic

therapy. The rate of clot formation, the strength of the clot, and the impact

of any lysis can be observed. The presence of disseminated intravas-cular

coagulation can be evaluated, as can the effect of heparin or heparinoid

activity. In addition, plate-let function can be assessed, including the

effects of platelet inhibition.

Related Topics