Term 3 Unit 3 | History | 7th Social Science - Jainism in Tamil Nadu | 7th Social Science : History : Term 3 Unit 3 : Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivika Philosophy in Tamil Nadu

Chapter: 7th Social Science : History : Term 3 Unit 3 : Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivika Philosophy in Tamil Nadu

Jainism in Tamil Nadu

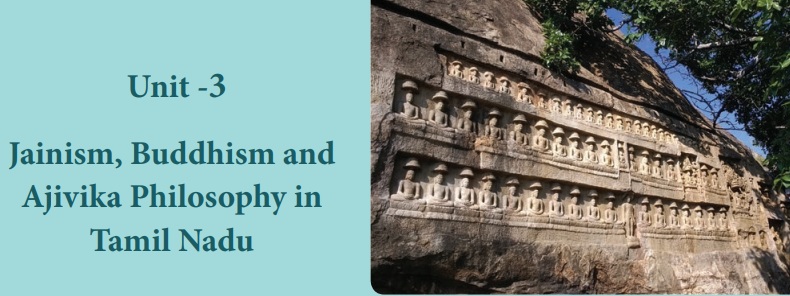

Unit -3

Jainism, Buddhism and

Ajivika Philosophy in Tamil Nadu

Learning Objectives

• To know the sources and literature of

heterodox religious sects: Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivikam

• To gain knowledge of the teachings of

Mahavira, Buddha and Gosala, the founder of Ajivika sect.

• To acquaint ourselves with the monuments of the above-mentioned religious sects in Tamil Nadu.

Jainism

in Tamil Nadu

Introduction

During the 6th century B.C. (BCE),

according to the Bigha Nitaya (an ancient Buddhist tract), as many as 62

different philosophical and religious schools flourished in India. However,

among these numerous sects, only the Ajivikas survived till the late medieval

times. But Jainism and Buddhism continued to flourish until the modern times.

Buddha and Mahavira, the founders of these two faiths, based their ethical

teachings against the sacrificial cult of the Vedic religion. Their teachings

were preserved and passed on through monks, who were drawn from various social

groups.

Sources and

Literature: Jainism

Mahavira's preaching was orally

transmitted by his disciples over the course of about one thousand years. In

the early period of Jainism, monks strictly followed the five great vows of

Jainism. Even religious scriptures were considered possessions and therefore

knowledge of the religion was never documented. Two hundred years after the

attainment of nirvana (death) of Mahavira, Jain scholars attempted to

codify the canon by convening an assembly at Pataliputra. It was the first Jain

council to debate the issue, but it ended as a failure because the council

could not arrive at a unanimous decision in defining the canon. A second

council held at Vallabhi, in the 5th century A.D., was, however, successful in

resolving the differences. This enabled the scholars of the time to explain the

principles of Jainism with certainty. Also, over time, many learned monks,

older in age and rich in wisdom, had compiled commentaries on various topics

pertaining to the Jain religion. Around 500 A.D. (CE) the Jain acharyas

(teachers) realised that it was extremely difficult to keep memorising the

entire Jain literature complied by the many scholars of the past and present.

In fact, significant knowledge was already lost and the rest was tampered with

modifications. Hence, they decided to document the Jain literature as known to

them

Five Great Vows of Jainism: 1. Non-violence – Ahimsa; 2. Truth–

Satya; 3. Non-stealing – Achaurya; 4. Celibacy/Chastity – Brahmacharya; 5.

Non-possession – Aparigraha.

A major split occurred in Jainism

(1st century B.C.), giving rise to two major sects, namely Digambaras

and Swetambaras. Both the Digambaras and the Swetambaras

generally acknowledge the Agama Sutras to be their early literature,

while they do differ with regard to their content and interpretation.

Jain Literature

Jain literature is generally

classified into two major categories.

1. Agama Sutras

Agama

Sutras consists of many sacred books of the Jain religion. They have been

written in the Ardha-magadhi Prakrit language. Containing the direct preaching

of Mahavira, consisting of 12 texts, they were originally compiled by immediate

disciples of Mahavira. The 12th Agama Sutra is said to have been lost.

2. Non-Agama Literature

Non-Agama

literature includes commentary and explanation of Agama Sutras, and independent

works, compiled by ascetics and scholars. They are written in many languages such as Prakrit,

Sanskrit, old Marathi, Rajasthani, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, German and

English. Recognition was given to 84 books, and among them, there are 41

sutras, 12 commentaries and one Maha Bhasya or great commentary. The 41

sutras include 11 Angas (scriptures followed by Swetambaras),

12 Upangas (instructions manuals), five Chedas (rules of conduct

for the monks), five Mulas (basic doctrine of Jainism) and eight

miscellaneous works, such as Kalpasutra of Bhadrabahu. It is believed

that the Panchatantra has a great amount of Jain influence.

The Jainacharitha of Kalpa Sūtra is a Jain text containing

the biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras, notably Parshvanatha, founder of

Jainism as well as the first Tirthankara, and Mahavira, the last and the 24th

Tirthankara. This work is ascribed to Bhadrabahu, who along with Chandragupta

Maurya migrated to Mysore (about 296 B.C.) and settled there.

Tirthankaras are those who have

attained nirvana and made a passage from this world to the next.

In addition to these, we have some

Jain texts composed in Indian vernacular languages such as Hindi, Tamil and

Kannada. Jivaka Chintamani, a Tamil epic poem, is a good example,

composed in the tradition of Sangam literature by a Jain saint named

Tiruthakkathevar. It narrates the life of a pious king who rose to prominence

by his own merit only to become an ascetic in the end. Another scholarly work

in Tamil, Naladiyar, is also attributed to a Jain monk. Thirukkural was

composed by Tiruvalluvar, believed to be a Jain scholar.

Jains in Tamil Nadu

There is a clear evidence of the

movements of the Jains from Karnataka to the Kongu region (Salem, Erode and

Coimbatore areas), to the Kaveri Delta (Tiruchirapalli) southwards into

Pudukkottai region (Sittannavasal) and finally into the Pandya kingdom

(Madurai, Ramanathapuram and Tirunelveli districts). Tamils broadly come under Digambara

sect. It is believed that the Kalabhras were the patrons of Jainism.

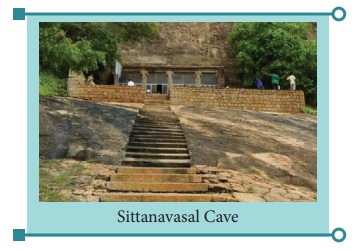

The Sittanavasal Cave

Temple

Sittanavasal cave in Pudukkottai

district is located on a prominent rock that stands 70 m above the ground. It

has a natural cavern, known as Eladipattam, at one end, and a rock-cut cave

temple at the other. Behind the fenced cavern, there are 17 rock beds marked on

the floor. The stone berths aligned in rows are believed to have served as a

Jain shelter. The largest of these ascetic beds contains a Tamil-Brahmi

inscription that dates to the 2nd century B.C. There are more inscriptions in

Tamil from the 8th century A.D., bearing the names of monks. It is believed

that they should have spent their lives in isolation here.

The Sittanavasal cave temple, named

Arivar Koil, lies on the west off the hillock.

The facade of the temple is simple,

with four rock-cut columns. Constructed in the early Pandya period, in the 7th

century A.D. , it has a hall in the front called the Ardha-mandapam and a

smaller cell at the rear, which is the garbha graha (sanctum sanctorum).

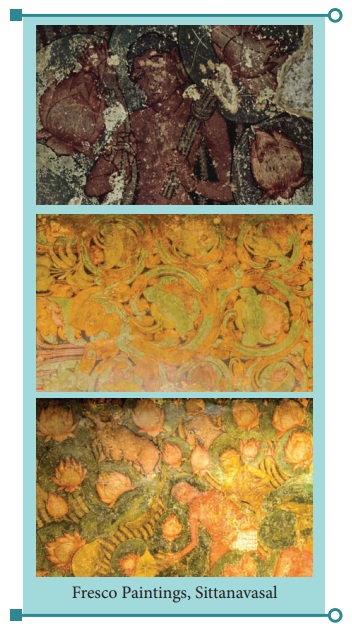

The murals in the temple resemble

the frescoes of the famous Ajanta caves. The Archaeological Survey of India

(ASI) took over the caves only in 1958. Thereafter it took two decades to cover

the cave and regulate the entry of visitors. There are the bas- relief figures

of Tirthankaras on the left wall of the hall and acharyas on the right before

one enters the inner chamber, the sanctum sanctorum.

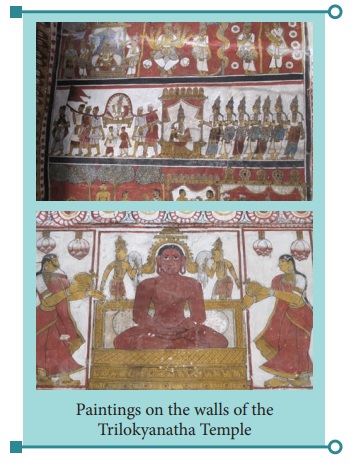

Jains in

Kanchipuram (Tiruparuttikunram)

Jainism

flourished during the Pallava reign. In hiswritings,Chinesetraveller Hiuen

Tsang has mentioned about the presence of a large number of Buddhists andJains

during his visit to the Pallava country in 7th century A.D. Most of the Pallava

rulers were Jains. Mahendravarman was a Jain initially. The two Jain temples in

Kanchipuram are Trilokyanatha Jinaswamy Temple at Tiruparuttikunram, on the

banks of the river Palar, and the Chandra Prabha temple dedicated to the

Tirtankara named Chandraprabha. The architecture of these temples is in Pallava

style, but it has deteriorated in due course of time. During the Vijayanagar

rule (1387), Irugappa, a disciple of Jaina-muni Pushpasena; and a minister of

Vijayanagar King Harihara II (1377-1404), expanded the Trilokyanatha Temple by

adding the Sangeetha mandapa. The grand murals were added only at this time.

Mural paintings in the temples show

scenes from the lives of Tirtankaras. Unfortunately the paintings of the

Trilokyanatha temple at Tiruparuttikunram have been ruined by over-painting

done during renovation. There is rich inscriptional evidence inside the second

shrine, the Trikuda Basti, containing information on the development of the

temple, and the contributions of various donors over the centuries.

In the Kanchipuram district, apart

from Tiruparuttikunram, Jain vestiges have been found over the years in many

villages across the state.

The total population of Jains

in Tamil Nadu is 83,359 or 0.12 per cent of the population as per the 2011

census.

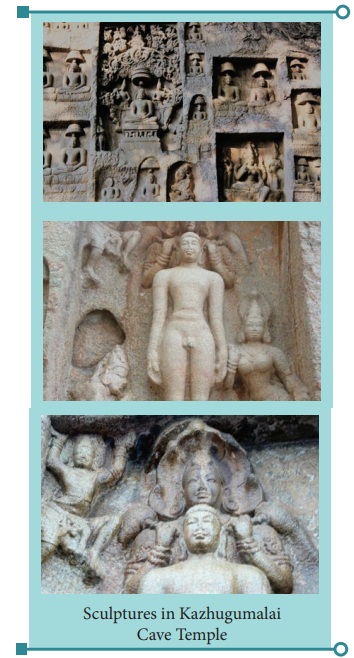

Kazhugumalai

Jain Rock-Cut Temple

The

8th centuryKazhugumalai temple in Kovilpatti taluk inThoothukudi district marks

the revival of Jainism in Tamil Nadu.This cave temple was built by King

Parantaka Nedunjadaiyan of the Pandyankingdom. Polished rock-cut cave beds, popularly known as Panchavar

Padukkai at Kazhugumalai cavern host the figures of not only the Tirtankaras

but also the figures of yakshas and yakshis (Male and Female

attendants respectively).

Jain Temples in other

parts of Tamil NaduVellore

Fourteen Jain monk beds, dating back

to the 5th century A.D., have been excavated inside three caverns on top of a

hill in Vellore district. The beds are found at the Bhairavamalai in Latheri,

Katpadi taluk, Vellore district. Of the three caverns, two of them house beds.

One houses four rock beds while the other houses one bed. Unlike many rock beds

found elsewhere, these ones have no head-rests.

Tirumalai

Tirumalai

is a Jain temple in a cave complex located near Arni town in Tiruvannamalai

district in Tamil Nadu. The complex, dated to the 12th century A.D., includes

three Jain caves, two Jain temples and a 16-metre-high sculpture of Neminatha,

the 22nd Tirthankara. This image of Neminatha is considered to be the tallest

Jain image in Tamil Nadu.

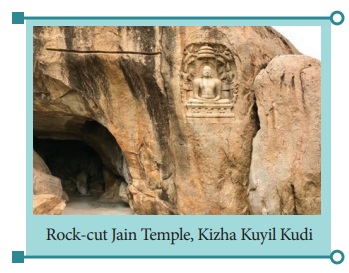

Madurai

There

are 26 caves, 200 stone beds, 60 inscriptions and over 100 sculptures in and

around Madurai. The Kizha Kuyil Kudi is a striking example. This hillock is 12

kilometres west of Madurai, on the Madurai–Theni Highway. The sculptures are

assigned to the period of Parantaka Veera Narayana Pandyan who ruled from A.D.

860 to 900. There are eight sculptures. The images of Rishab Nath or Adinath,

Mahavira, Parshvanath and Bahubali are found here.

Contribution to

Education

Jaina monasteries and temples also

served as seats of learning. Education was imparted in these institutions to the

people irrespective of caste and creed. The Jainas propagated their doctrines

and proved to be a potential media of mass education. The Bhairavamalai we have

mentioned earlier is situated near a small village called Kukkara Palli.

‘Palli’ is an educational centre of Jains and villages bearing the suffix of

Palli are common in many places in Tamil Nadu.

The educational institutions had

libraries attached to them. Several books were written by the preachers of

Jainism, highlighting the important aspects of Jainism. The permission for

women to enter into the order provided an impetus to the spread of education

among women.

Related Topics