Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Impulse Control Disorders

Intermittent Explosive Disorder

Intermittent

Explosive Disorder

Definition

Patients with intermittent explosive disorder have a problem with their temper (see DSMIV-TR criteria). This definition highlights the centrality of impulsive aggression in intermittent explo-sive disorder. Impulsive aggression, however, is not specific to intermittent explosive disorder. It is a key feature of several psy-chiatric disorders and nonpsychiatric conditions and may emerge during the course of yet other psychiatric disorders. Therefore, the definition of intermittent explosive disorder as formulated in the DSM-IV-TR is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion. As described in criterion C, a diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder is made only after other mental disorders that might ac-count for episodes of aggressive behavior have been ruled out. The individual may describe the aggressive episodes as “spells” or “attacks”. The symptoms appear within minutes to hours and, regardless of the duration of the episode, may remit almost as quickly. As in other impulse control disorders, the explosive be-havior may be preceded by a sense of tension or arousal and is followed immediately by a sense of relief or release of tension Although not explicitly stated in the DSM-IV-TR definition of intermittent explosive disorder, impulsive aggressive behavior may have many motivations that are not meant to be includedwithin this diagnosis. Intermittent explosive disorder should not be diagnosed when the purpose of the aggression is monetary gain, vengeance, self-defense, social dominance, or expressing a political statement or when it occurs as a part of gang behavior. Typically, the aggressive behavior is egodystonic to individuals with intermittent explosive disorder, who feel genuinely upset, remorseful, regretful, bewildered, or embarrassed about their impulsive aggressive acts.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Since the

second half of the 19th century, two main lines of explanation, which are to a

large extent complementary, have been developed to account for the existence of

individuals with episodic impulsive aggression. One line of explanation viewed

the etiology of impulsive aggression as stemming from the effects of early

childhood experiences and possibly childhood trauma on the development of

self-control, frustration tolerance, planning ability and gratification delay,

which are all important for self-prevention of impulsive aggressive outbursts.

Early experiences with “good-enough” mothering that fosters phase-appropriate

delay of gratification and the development of the potential for im-itation and

identification with the mother are considered impor-tant for normal

development. Too much or too little frustration, as well as overgratification

or undergratification, may impair the normal development of the ability to

anticipate frustration and delay gratification.

A second

line of explanation, which has yielded numer-ous positive findings during the

past 15 years, views impulsive aggression as the result of variations in brain

mechanisms that mediate behavioral arousal and behavioral inhibition. A rapidly

growing body of evidence has shown that impulsive aggression may be related to

defects in the brain serotonergic system, which acts as an inhibitor of motor

activity. Although the majority of studies involved patients who suffered from

impulsive aggression in the context of disorders other than intermittent

explosive dis-order, their findings may be relevant to the behavioral dimension

of impulsive aggression, of which intermittent explosive disorder is a “pure”

form. A number of researchers have confirmed a rela-tionship between levels of

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the CSF and impulsive or aggressive

behaviors. Others have divided aggressive behaviors into impulsive and

nonimpulsive forms, and found that reduced CSF 5-HIAA levels were corre-lated

with impulsive aggression only. Pharmacological challenge studies of the

serotonergic system have also demonstrated that low serotonergic responsiveness

(as measured by the neuroen-docrine response to serotonergic agonists) correlates

with scores of impulsive aggression. Studies of impulsive aggression among

alcoholics have further defined a probable relationship between such behaviors

and diminished serotonergic function.

The

literature on serotonin and suicide, which may be viewed as an extreme form of

self-directed aggression, suggests another link between serotonin and

aggression. Postmortem studies found that brain stem levels of serotonin were

decreased in suicide victims, and reduced imipramine binding, which is thought

to be associated with reduced presynaptic serotonergic binding sites, was found

in the brains of suicide completers. Furthermore, an increase in postsynaptic

5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT2) receptors was found in the brains of

suicide completers, and this finding was confirmed in subsequent studies. An

increase in 5-HT2 receptors, which are thought to be mostly

postsynaptic, may reflect the brain’s reaction to a decrease in functional

sero-tonergic neurons, with consequent upregulation of postsynaptic serotonin

binding sites

Another

line of neurobiological evidence links impulsive aggression with dysfunction of

the prefrontal cortex. Studies of neuropsychiatric patients with localized

structural brain lesions have demonstrated that some bilateral lesions in the

prefrontal cortex may be specifically associated with a chronic pattern of

impulsive aggressive behaviors. Neurological studies suggest that the

prefrontal cortical regions associated with impulsive aggression syndromes are

involved in the processing of affec-tive information and the inhibition of

motor responsiveness, both of which are impaired in patients with impulsive

aggres-sion. Interictal episodes of aggression may occur among some individuals

with epilepsy. In a quantitative MRI study of such episodes among individuals

with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Woermann et

al., 2000) three groups (24 TLE patients with ag-gressive behavior, 24 TLE

patients without such behavior and 35 nonpatient controls) were compared. The

researchers concluded that the aggressive behavior was associated with a

reduction of frontal neocortical gray matter.

Biological

studies implicate the serotonergic system and the prefrontal cortex in the

pathogenesis of impulsive aggression. The diagnosis of intermittent explosive

disorder is sometimes considered in forensic settings; the biological

correlates of im-pulsive aggression focus attention on, but do not solve, the

com-plicated problem of personal responsibility for impulsive violent acts that

are correlated with objective biological findings. Data from a study of

visual-evoked potentials and EEGs in a large group of children and adolescents

who demonstrated aggressive behavior also suggest that such behavior may be

associated with altered innate characteristics of central nervous system

function (Bars et al., 2001).

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis

Phenomenology and Variations in Presentation

Episodes

of violent behavior appear in several common psychi-atric disorders such as

antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder and substance

use disorders and need to be distinguished from the violent episodes of

patients with intermit-tent explosive disorder, which are apparently rare. The

study of Felthous and coworkers (1991), in which 15 men with rigorously

diagnosed DSM-III-R intermittent explosive disorder were iden-tified from among

a group of 443 men who complained of vio-lence, permitted some systematic

observations about the “typical violent episode” as reported by patients with

intermittent explo-sive disorder.

In the

vast majority of instances, the subjects with inter-mittent explosive disorder

identified their spouse, lover, or girl-friend or boyfriend as a provocateur of

their violent episodes. Only one was provoked by a stranger. For most, the reactions

occurred immediately and without a noticeable prodromal pe-riod. Only one

subject stated that the outburst occurred between 1 and 24 hours after the

perceived provocation. All subjects with intermittent explosive disorder denied

that they intended the outburst to occur in advance. Most subjects remained

well oriented during the outbursts, although two claimed to lose track of where

they were. None lost control of urine or bowel function during the episode.

Subjects reported various degrees of subjective feelings of behavioral

dyscontrol. Only four felt that they completely lost control. Six had good

recollection of the event afterward, eight had partial recollection and one

lost memory of the event afterward. Most subjects with intermit-tent explosive

disorder attempted to help or comfort the victim afterwards.

Assessment

Special Issues in the Psychiatric Examination and History

The

DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder is essentially a

diagnosis of exclusion, and the psychiatrist should evaluate and carefully rule

out more common diagnoses that are associated with impulsive violence. The

lifelong nonremitting history of impulsive aggression associated with

antisocial person-ality disorder and borderline personality disorder, together

with other features of antisocial behavior (in antisocial personality disorder)

or impulsive behaviors in other spheres (in borderline personality disorder),

may distinguish them from intermittent explosive disorder, in which baseline

behavior and functioning are in marked contrast to the violent outbursts. Other

features of borderline personality disorder such as unstable and intense interpersonal

relationships, frantic efforts to avoid abandonment and identity disturbance

may also be elicited by a careful history. More than in most psychiatric

diagnoses, collateral information from an independent historian may be

extremely helpful. This is especially true in forensic settings. Of note,

patients with in-termittent explosive disorder are usually genuinely distressed

by their impulsive aggressive outbursts and may voluntarily seek psychiatric

help to control them. In contrast, patients with an-tisocial personality

disorder do not feel true remorse for their actions and view them as a problem

only insofar as they suffer their consequences, such as incarceration and

fines. Although patients with borderline personality disorder, like patients

with intermittent explosive disorder, are often distressed by their im-pulsive

actions, the rapid development of intense and unstable transference toward the

psychiatrist during the evaluation period of patients with borderline

personality disorder may be helpful in distinguishing it from intermittent

explosive disorder.

Other

causes of episodic impulsive aggression are sub-stance use disorders, in

particular alcohol abuse and intoxication. When the episodic impulsive

aggression is associated only with intoxication, intermittent explosive

disorder is ruled out. How-ever, as discussed earlier, intermittent explosive

disorder and al-cohol abuse may be related, and the diagnosis of one should

lead the psychiatrist to search for the other.

Neurological

conditions, such as dementias, focal frontal lesions, partial complex seizures

and postconcussion syndrome after recent head trauma, may all present as

episodic impulsive aggression and need to be differentiated from intermittent

explo-sive disorder. Other neurological causes of impulsive aggression include

encephalitis, brain abscess, normal-pressure hydrocepha-lus, subarachnoid

hemorrhage and stroke. In these instances, the diagnosis would be personality

change due to a general medical condition, aggressive type, and it may be made

with a careful his-tory and the characteristic physical and laboratory

findings.

Individuals

with intermittent explosive disorder may have comorbid mood disorders. Although

the diagnosis of a manic epi-sode excludes intermittent explosive disorder, the

evidence for serotonergic abnormalities in both major depressive disorder and

impulse control disorders supports the clinical observation that impulsive

aggression may be increased in depressed patients, leading ultimately to

completed suicide.

Physical Examination and Laboratory Findings

The

physical and laboratory findings relevant to the diagnosis of intermittent

explosive disorder and the differential diagnosis of impulsive aggression may

be divided into two main groups: those associated with episodic impulsive

aggression but not diagnostic of a particular disorder and those that suggest

the diagnosis of a psychiatric or medical disorder other than intermittent

explosive disorder. No laboratory or physical findings are specific for

inter-mittent explosive disorder.

The first

group of findings that are associated with impul-sive aggression across a

spectrum of disorders includes soft neuro-logical signs such as subtle

impairments in hand–eye coordination and minor reflex asymmetries. These signs

may be elicited by a comprehensive neurological examination and simple

pencil-and-paper tests such as parts A and B of the Trail Making Test.

Mea-sures of central serotonergic function such as CSF 5-HIAA lev-els, the

fenfluramine neuroendocrine challenge test, and positron emission tomography of

prefrontal metabolism also belong to this group. Although these measures

advanced our neurobiological understanding of impulsive aggression, their

utility in the diagno-sis of individual cases of intermittent explosive

disorder and other disorders with impulsive aggression is yet to be

demonstrated.

The

second group of physical and laboratory findings is useful in the diagnosis of

causes of impulsive aggression other than intermittent explosive disorder. The

smell of alcohol on a patient’s breath or a positive alcohol reading with a

Breathalyzer may help reveal alcohol intoxication. Blood and urine toxicology

screens may reveal the use of other substances, and track marks on the forearms

may suggest intravenous drug use. Partial com-plex seizures and focal brain

lesions may be evaluated by use of the EEG and brain imaging. In cases without

a grossly abnormal neurological examination, magnetic resonance imaging may be

more useful than computed tomography of the head. Magnetic resonance imaging

can reveal mesiotemporal scarring, which may be the only evidence for a latent

seizure disorder, sometimes in the presence of a normal or inconclusive EEG.

Diffuse slowing on the EEG is a nonspecific finding that is probably more

com-mon in, but not diagnostic of, patients with impulsive aggression.

Hypoglycemia, a rare cause of impulsive aggression, may be de-tected by blood

chemistry screens.

Differential Diagnosis

As

discussed earlier, the differential diagnosis of intermittent ex-plosive

disorder covers the differential diagnosis of impulsivity and aggressive

behavior in general. Aggression and impulsivity are defined as follows:

Aggression

is defined as forceful physical or verbal action, which may be appropriate and

self-protective or inappropriate as in hostile or destructive behavior. It may

be directed against another person, against the environment, or toward the

self. The psychiatric nosology of aggression is still preliminary. Impul-sivity

is defined as the tendency to act in a sudden, unpremedi-tated, and excessively

spontaneous fashion.

The

diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder should be con-sidered only after

all other disorders that are associated with impulsivity and aggression have

been ruled out. Chronic impul-sivity and aggression may occur as part of a

cluster B person-ality disorder (antisocial and borderline); during the course

of substance use disorders and substance intoxication; in the setting of a

general medical (usually neurological) condition; and as part of disorders

first diagnosed during childhood and adolescence such as conduct disorder,

oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and

mental retardation. In addition, impulsive aggression may appear during the

course of a mood disorder, especially during a manic episode, which precludes

the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder, and during the course of an

agitated depressive episode. Impulsive aggression may also be an associated

feature of schizophrenia, in which it may occur in response to hallucinations

or delusions. Impulsive aggression may also appear in variants of OCD, which

may pres-ent with concurrent impulsive and compulsive symptoms.

A special

problem in the differential diagnosis of impulsive aggression, which may arise

in forensic settings, is that it may rep-resent purposeful behavior. Purposeful

behavior is distinguished from intermittent explosive disorder by the presence

of motivation and gain in the aggressive act, such as monetary gain, vengeance,

or social dominance. Another diagnostic problem in forensic settings is

malingering, in which individuals may claim to have intermittent explosive

disorder to avoid legal responsibility for their acts.

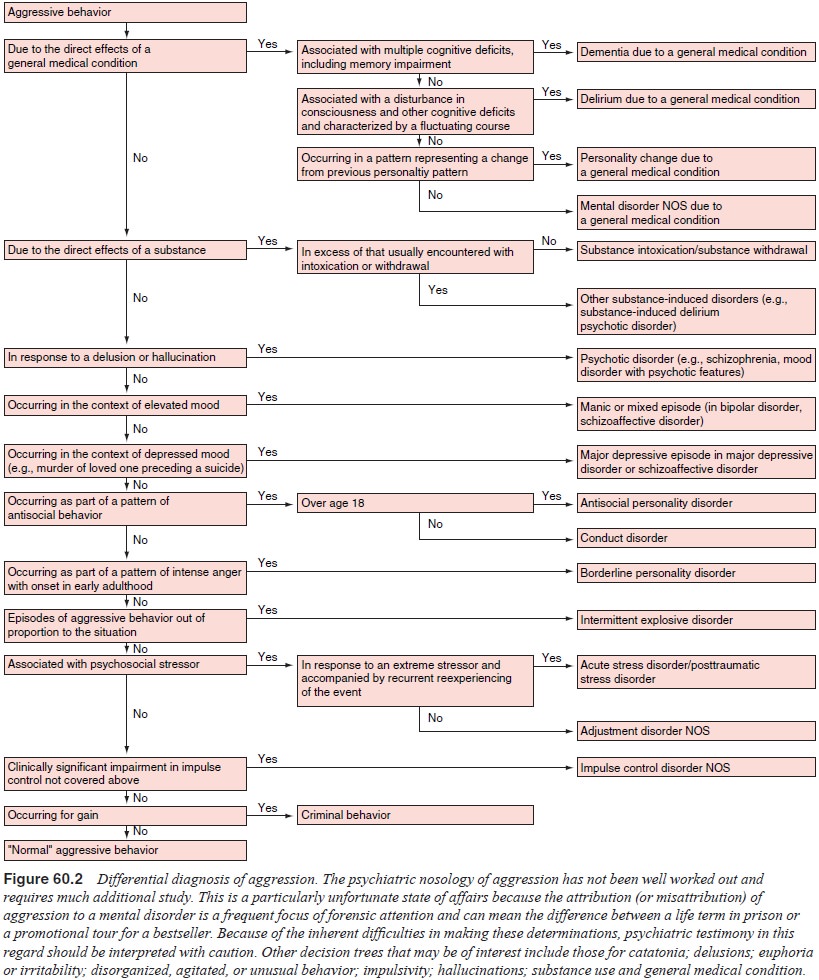

Figure

60.2 presents the differential diagnosis of aggression

Epidemiology

Prevalence and Incidence

Intermittent

explosive disorder has been subjected to little systematic study. The

exclusionary criterion in the DSM-IV-TR definition (criterion C) reflects an

ongoing debate over the boundaries of this disorder. In an early study of the

prevalence of DSM-III-R intermittent explosive disorder among violent men,

Felthous and colleagues (1991) found that of 443 sub-jects who complained of

violence, only 15 (3.4%) met crite-ria for intermittent explosive disorder.

However, the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)

(Kessler et al., 2005) found that

intermittent explosive disorder (12 month prevalence 2.6%) was as nearly common

as panic disorder (12 month prevalence 2.7%).

Comorbidity

The

DSM-IV-TR definition of intermittent explosive disorder allows signs of

generalized impulsivity or aggressiveness to be present between episodes. It

also allows the psychiatrist to give an additional diagnosis of intermittent

explosive disorder in the presence of another disorder if the episodes are not

better ac-counted for by the other disorder. The clinical reality is that most

individuals who have intermittent episodes of aggressive behavior also have

some impulsivity between episodes and often present with other past or current

psychiatric disorders. There is minimal research-based data available regarding

comorbidity. But the lit-erature on the comorbidity of impulsive aggressive

episodes sug-gests that it often occurs with three classes of disorders:

·

Personality disorders, especially antisocial

personality disor-der and borderline personality disorder. By definition,

antiso-cial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder are

chronic and include impulsive aggression as an essential feature. Therefore,

their diagnosis effectively excludes the di-agnosis of intermittent explosive

disorder (Figure 60.2).

·

A history of substance use disorders, especially

alcohol abuse. A concurrent diagnosis of substance intoxication excludes the

diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder. However, many patients with

intermittent explosive disorder report past or family histories of substance

abuse, and in particular alcohol abuse. In light of evidence linking personal

and family history of alcohol abuse with impulsive aggression and the evidence

(reviewed later) linking both with low central serotonergic function, this

connection may be clinically relevant. There-fore, when there is evidence

suggesting that alcohol abuse may be present, a systematic evaluation of

intermittent explo-sive disorder is warranted, and vice versa.

·

Neurological disorders, especially severe head

trauma, partial complex seizures, dementias and inborn errors of metabolism.

Intermittent explosive disorder is not diagnosed if the aggres-sive episodes

are a direct physiological consequence of a gen-eral medical condition. Such

cases would be diagnosed as per sonality change due to a general medical

condition, delirium, or dementia. However, individuals with intermittent

explo-sive disorder often have nonspecific findings on neurologi-cal

examination, such as reflex asymmetries, mild hand–eye coordination deficits,

and childhood histories of head trauma with or without loss of consciousness.

Their EEGs may show nonspecific changes. Such isolated findings are com-patible

with the diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder and preempt the diagnosis

only when they are indicative of a definitely diagnosable general medical or

neurological condi-tion. Such “soft” neurological signs may be diagnosed by a

full neurological examination and neuropsychological testing

McElroy

and coworkers (McElroy et al., 1998;

McElroy, 1999) studied 27 individuals who had symptoms that met criteria for

intermittent explosive disorder (IED) and reported: “Twenty-five (93%) subjects

had lifetime DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of mood disorders; 13 (48%), substance use

disorders; 13 (48%), anxiety disorders; 6 (22%), eating disorders; and 12

(44%), an impulse control disorder other than intermittent explosive disorder.

Sub-jects also displayed high rates of comorbid migraine headaches.

First-degree relatives displayed high rates of mood, substance use, and impulse

control disorders”.

Some

children with Tourette’s disorder may be prone to rage attacks. The clinical

manifestation of these rage attacks are similar to IED and may be more common

among children with To-urette’s who have comorbid mood disorders. On the basis

of these observations, the rage attacks of these children may flow from an

underlying dysregulation of brain function (Budman et al., 2000).

Course, Natural History and Prognosis

Little

systematic study has been done on the course of inter-mittent explosive

disorder. The onset of the disorder appears to be from late adolescence to the

third decade of life, and it may be abrupt and without a prodromal period.

Intermittent explosive disorder is apparently chronic and may persist well into

middle life unless treated successfully. In some cases, it may decrease in

severity or remit completely with old age.

Treatment

Given the

rarity of pure intermittent explosive disorder, it is not surprising that few

systematic data are available on its response to treatment and that some of the

recommended treatment ap-proaches to intermittent explosive disorder are based

on treat-ment studies of impulsivity and aggression in the setting of other

mental disorders and general medical conditions. Thus, no stan-dard regimen for

the treatment of intermittent explosive disorder can be recommended at this

time.

Psychological Treatment

Lion

(1992) has described the major psychotherapeutic task of teaching individuals

with intermittent explosive disorder how to recognize their own feeling states and

especially the affective state of rage. Lack of awareness of their own mounting

anger is presumed to lead to the build-up of intolerable rage that is then

discharged suddenly and inappropriately in a temper outburst. Patients with

intermittent explosive disorder are therefore taught how to first recognize and

then verbalize their anger appropri-ately. In addition, during the course of

insight-oriented psycho-therapy, they are encouraged to identify and express

the fantasies surrounding their rage. Group psychotherapy for temper-prone

patients has also been described. The cognitive–behavioral model of

psychological treatment may be usefully applied to problems with anger and rage

management.

Somatic Treatments

Several

classes of medications have been used to treat inter-mittent explosive

disorder. The same medications have also been used to treat impulsive

aggression in the context of other disorders. These included beta-blockers

(propranolol and meto-prolol), anticonvulsants (carbamazepine and valproic

acid), lithium, antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin

reuptake inhibitors) and antianxiety agents (lorazepam, alpra-zolam and

buspirone). Mattes (1990) compared the effectiveness of two commonly used

agents, carbamazepine and propranolol, for the treatment of rage outbursts in a

heterogeneous group of patients. He found that although carbamazepine and

propranolol were overall equally effective, carbamazepine was more effective in

patients with intermittent explosive disorder and propranolol was more

effective in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactiv-ity disorder. A

substantial body of evidence supports the use of propranolol – often in high

doses – for impulsive aggression in patients with chronic psychotic disorders

and mental retardation. Lithium has been shown to have antiaggressive

properties and may be used to control temper outbursts. In patients with

comor-bid major depressive disorder, OCD, or cluster B and C personal-ity

disorders, SSRIs may be useful. Overall, in the absence of more controlled

clinical trials, the best approach may be to tailor the psychopharmacological

agent to coexisting psychiatric co-morbidity. In the absence of comorbid

disorders, carbamazepine, titrated to antiepileptic blood levels, may be used

empirically.

Related Topics