Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Impulse Control Disorders

Impulse Control Disorders

Impulse Control Disorders

The trait

of impulsivity has been the subject of increasing in-terest in psychiatry. New

research findings seem to associate various forms of impulsive behavior with

biological markers of altered sero-tonergic function. These include impulsive

suicidal behavior, impul-sive aggression and impulsive fire-setting.

Impulsivity is also a focus of interest in the increasing attention paid to the

behavioral phenome-nology of borderline personality disorder. In all these

circumstances, impulsivity is conceived of as the rapid expression of unplanned

be-havior, occurring in response to a sudden thought. (This is seen by some as

the polar opposite of obsessional behavior, in which delibera-tion over an act

may seem never-ending.) Although the sudden and unplanned aspect of the

behavior may be present in the impulse dis-orders (such as in intermittent

explosive disorder and kleptomania), the primary connotation of the word

impulsivity, as used to describe these conditions, is the irresistibility of

the urge to act.

The

National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) (Kessler et al., 2005) extended the definition of impulse control disorders

described to include intermittent explo-sive disorder, attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant

disorder (ODD). This decision was based on the fact that ADHD and anger

symp-toms often persist throughout adulthood. The NCS-R found that the combined

lifetime prevalence for these disorders is greater than that of mood (20.8%) or

substance abuse disorders (14.6%). Impulse control disorders in the extended

definition had a 12 month prevalence of 8.9% and a lifetime prevalence of

24.8%. Moreover, this group was judged to have a greater proportion functioning

at the serious level than either anxiety or substance abuse disor-ders. with

approximately half of all lifetime cases receiving no treatment. An important

objective in studying the impulse control disorders in this fashion was to

highlight how common hostility and aggression are in psychiatric disorders, two

dimensions often not receiving sufficient diagnostic consideration but which

are significantly present as comorbidities with other disorders.

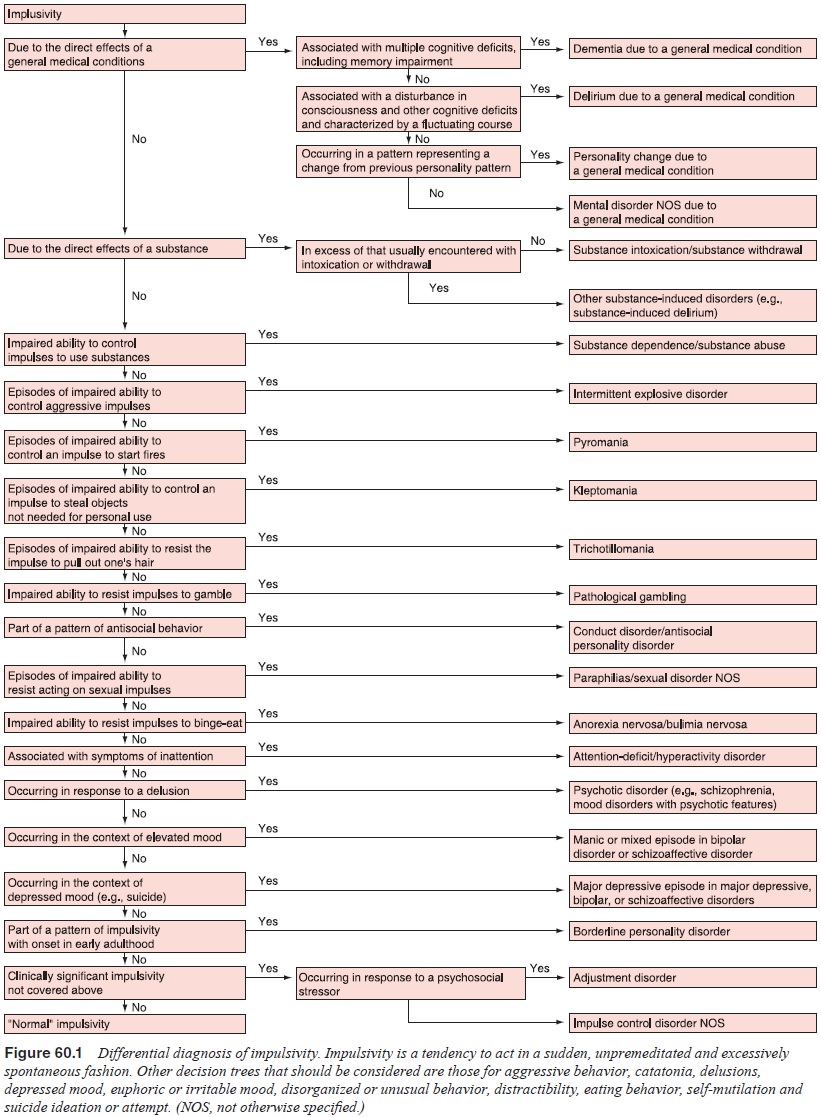

Trichotillomania,

pyromania and pathological gambling may involve episodes in which a sudden

desire to commit the act of hair-pulling, fire-setting, or gambling is followed

by rapid expression of the behavior. But in these conditions, the individual

may spend considerable amounts of time fighting off the urge, trying not to

carry out the impulse. The inability to resist the impulse is the common core

of these disorders, rather than the rapid transduction of thought to action. A

decision tree for the differen-tial diagnosis of impulsive behaviors may be

seen in Figure 60.1.

Other

than sharing the essential feature of impulse dyscon-trol, it is unclear

whether the conditions bear any re-lationship to each other. Emerging

perspectives on the neurobiology of impulsivity suggest that impulsive

behaviors, across diagnostic boundaries, may share an underlying

pathophysiological diathesis. As noted earlier, markers of altered serotonergic

neurotransmission have been associated with a variety of impulsive behaviors:

suicid-ality, aggressive violence, pyromania and conduct disorder. These

observations have led to speculation that decreased serotonergic

neurotransmission may result in decreased ability to control urges to act. In

accord with this model, these disorders may be varying expressions of a single

disturbance – or closely related disturbances – of serotonergic function.

Although such markers of altered sero-tonergic function have been demonstrated

among impulsive fire-setters and impulsive violent offenders, there is, as yet,

insufficient research on these conditions to accept or dismiss this theory.

It has

been noted that these conditions are embedded in similar patterns of

comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders. High rates of comorbid mood

disorder and anxiety disorder ap-pear typical of these disorders. This

contextual similarity, com-bined with the common feature of impulsivity, may

further sup-port the notion that these conditions are – at the level of core

diathesis – related to each other.

Although

these conditions have historically been consid-ered uncommon, later

investigations suggest that some of them may be fairly common.

Trichotillomania, for example, was once considered rare. However, surveys

indicate that the lifetime prev-alence of the condition may exceed 1% of the

population. Patho-logical gambling may be present in up to 3% of the

population. Extrapolation from the known incidence of comorbid conditions

suggests that kleptomania may have a 0.6% incidence. It would seem reasonable

to suspect that individuals with pyromania and kleptomania may seek to avoid

detection and may therefore be underrepresented in research and clinical

samples.

Treatment

protocols for these conditions have not been well studied. Few treatment

studies of these specific conditions have been performed. Attempts to treat

these conditions are usu-ally formulated by extrapolation from treatments that

have been developed for other conditions.

The aggressive quality of kleptomania, pyromania and intermittent explosive disorder and the self-damaging nature of trichotillomania and pathological gambling have presented tempting substrates for the application of traditional analytical concepts. From this perspective, these behaviors have been seen as symptomatic expressions of unconscious conflict, often sexual in nature. Other formulations include desires for oral gratification and masochistic wishes to be caught and punished, motivated by a harsh, guilt-inducing superego. The increasing influence of object relations theory was reflected in increasing emphasis on narcissistic psychopathology and histories of disturbed early par-enting. As successful behavioral interventions were developed for other conditions, case reports of behavioral treatments for these conditions emerged. Reports of hypnotic treatments are also prominent in the literature.

The

contemporary medical and psychological literature reflects, not surprisingly,

prevailing general interests in current research and theory. As pharmacological

treatments are applied to an increasing range of symptoms, the impulse

disorders present new opportunities to widen the application of thymoleptic and

anxiolytic and, more recently, (atypical) neuro-leptic medication. Some are

reconceptualizing the idea of mood and obsessional disorders, widening them

into affective and ob-sessional spectrums, encompassing various impulse

disorders into these domains.

As part

of the ongoing dynamic of evolving theory, the very concept of impulsivity is

still in ferment. Attempts further to refine the idea of impulsivity are

reflected in a perspective of-fered by Van Ameringen and associates (1999). In

a discussion of preliminary evidence indicating that trichotillomania may be

preferentially responsive to neuroleptics, they suggest that indi-viduals with

trichotillomania may have features in common with the subgroup of obsessive

compulsive disorder (OCD) patients who have comorbid Tourette’s syndrome (TS).

These authors offer a thoughtful model, applying the idea of an “Impulsion”

(Shapiro and Shapiro, 1992), an action performed until a sense of “rightness”

is achieved, rather than a compulsion, which is de-signed to reduce an anxiety

brought on by an obsession. They go on to note one formulation of OCD, which

divides symptoms into three types: symmetry/hoarding, pure obsessions and contamina-tion/cleaning.

The symmetry/hoarding factor – impulsion-driven behavior – was differentially

related to OCD with comorbid TS. They point to recent data suggesting that the

OCD/TS subgroup is not as responsive to SSRI medication alone as other OCD sub-types,

but responds better to SSRI/neuroleptic combinations. These observations, taken

together with their report of enhanced response of trichotillomania to

neuroleptics, is the basis for their argument that trichotillomania should be

seen as more similar to OCD/TS then OCD, more impulsion than compulsion. The

idea of anxiously seeking “rightness” is consistent with the clinical

experience of many individuals with trichotillomania and is a thoughtful

addition to the other attributes associated with impul-sivity: anxiety

reduction, irresistibility of action and rapidity of its execution.

Trichotillomania

provides an example of the convergence of current research techniques and

treatment perspectives. The absence of new psychodynamic formulations would

seem to re-flect not an abandonment of dynamic theory but an acceptance that

such models are most useful in understanding individual patients rather than

providing universal explanations for the symptom. Dynamic considerations may be

useful in trying to understand why particular circumstances may provoke

episodes of the problem behavior for a particular individual.

Not all

these conditions are, as yet, receiving significant attention.

Trichotillomania, intermittent explosive disorder andpathological gambling have

become the focus of increasing inter-est. Kleptomania and pyromania, however,

remain stepchildren of research. Perhaps the legal implications of these

behaviors and their entanglement with similar, but not impulsively motivated,

behaviors complicate the availability of sufficient cases to facili-tate

research.

Because

of the limited body of systematically collected data, the following sections

largely reflect accumulated clinical experience. Therefore, the practicing

psychiatrist should be par-ticularly careful to consider the exigencies of

individual patients in applying treatment recommendations.

Related Topics