Chapter: Essential Microbiology: Fungi

Fungi and disease

Fungi and

disease

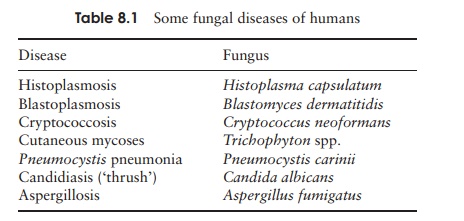

A limited number of fungi are pathogenic to humans

(Table 8.1). Mycoses (sing: mycosis)

in humans may be cutaneous, or systemic; in the latter, spores generally enter

the body by inhalation, but subsequently spread to other organ systems via the

blood, causing serious, even fatal disease.

Cutaneous mycoses are the

most common fungal infections found in humans, andare caused by fungi known as dermatophytes, which are able to utilise

the keratin of skin, hair or nails by secreting the enzyme keratinase. Popular names for such infections include ringworm and

athletes’ foot. They are highly contagious, but not usually serious conditions.

Systemic mycoses can be

much more serious, and include conditions such as histo-plasmosis and

blastomycosis. The former is caused by Histoplasma

capsulatum, and is associated with areas where there is contamination by

bat or bird excrement. It is thought that the number of people displaying

clinical symptoms of histoplasmosis rep-resents only a small proportion of the

total number infected. If confined to the lungs, the condition is generally

self-limiting, but if disseminated to other parts of the body such as the heart

or central nervous system, it can be fatal. The causative agents of both

diseases exhibit dimorphism; they exist in the environment as mycelia but

convert to yeast at the higher temperature of their human host.

Aspergillus

fumigatus is an example of an opportunistic pathogen, that is, an or-ganism which, although

usually harmless, can act as a pathogen in individuals whose resistance to

infection has been lowered. Other opportunistic mycoses include candidi-asis

(‘thrush’) and Pneumocystis

pneumonia. The latter is found in a high percentage of acquired immune

deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, whose immune defences have been

compromised. The causative organism, Pneumocystis

carinii, was previously con-sidered to be a protozoan, and has only been

classed as a fungus in the last decade, as a result of DNA/RNA sequence

evidence. It lives as a commensal in a variety of mammals, and is probably

transmitted to humans through contact with dogs.

The incidence of opportunistic mycoses has increased

greatly since the introduction of antibiotics, immunosuppressants and cytotoxic

drugs. Each of these either suppresses the individual’s natural defences, or

eliminates harmless microbial competitors, allowing the fungal species to

flourish.

Many fungi produce natural mycotoxins; these are secondary

metabolites, which, if consumed by humans,can cause food poisoning that can

sometimes be fatal. Certain species of mushrooms (‘toadstools’) including the

genus Amanita contain substances that

are highly poisonous to humans. Other examples of mycotoxin ill-nesses include

ergotism and aflatoxin poi-soning. Aflatoxins are carcinogenic toxins produced by Aspergillus

flavus that grows on stored peanuts. In theearly 1960s, the turkey industry

in the UK was almost crippled by ‘Turkey X disease’, caused by the consump-tion

of feed contaminated by A. flavus.

It is thought likely that all animals are parasitised

by one fungus or another. Extraordinary though it may seem, there are even

fungi that act as predators on small soil animals such as nematode worms,

producing constrictive hyphal loops that tighten, immobilising the prey.

Fungi also cause disease in plants, and can have a

devastating effect on crops of economic importance, either on the living plant

or in storage subsequent to harvest-ing. Rusts, smuts and mildews are all

examples of common plant diseases caused by fungi. The effects of fungi on

materials such as wood and textiles.

Related Topics