Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Eating Disorders

Etiology - Eating Disorders

ETIOLOGY

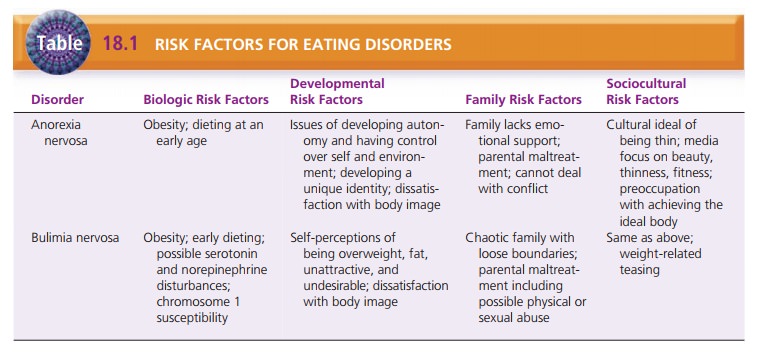

A specific cause for eating disorders is unknown. Initially,

dieting may be the stimulus that leads to their development. Biologic

vulnerability, developmental problems, and family and social influences can

turn dieting into an eating disor-der (Table 18.1). Psychologic and physiologic

reinforcement of maladaptive eating behavior sustains the cycle (Anderson &

Yager, 2005).

Biologic Factors

Studies of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have shown that

these disorders tend to run in families. Genetic vulnerability also might

result from a particular personal-ity type or a general susceptibility to

psychiatric disorders. Or it may directly involve a dysfunction of the

hypothala-mus. A family history of mood or anxiety disorders (e.g.,

obsessive–compulsive disorder) places a person at risk for an eating disorder

(Anderson & Yager, 2005).

Disruptions of the nuclei of the hypothalamus may pro-duce many of

the symptoms of eating disorders. Two sets of nuclei are particularly important

in many aspects of hunger and satiety

(satisfaction of appetite): the lateral hypothalamus and the ventromedial

hypothalamus. Defi-cits in the lateral hypothalamus result in decreased eating

and decreased responses to sensory stimuli that are impor-tant to eating.

Disruption of the ventromedial hypothala-mus leads to excessive eating, weight

gain, and decreased responsiveness to the satiety effects of glucose, which are

behaviors seen in bulimia.

Many neurochemical changes accompany eating dis-orders, but it is

difficult to tell whether they cause or result from eating disorders and the

characteristic symp-toms of starvation, binging, and purging. For example,

norepinephrine levels rise normally in response to eating, allowing the body to

metabolize and to use nutrients. Norepinephrine levels do not rise during

starvation, however, because few nutrients are available to metabo-lize.

Therefore, low norepinephrine levels are seen in clients during periods of

restricted food intake. Also, low epinephrine levels are related to the

decreased heart rate and blood pressure seen in clients with anorexia.

Increased levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin and its

precursor tryptophan have been linked with increased satiety. Low levels of

serotonin as well as low platelet levels of monoamine oxidase have been found

in clients with bulimia and the binge and purge subtype of anorexia ner-vosa

(Anderson & Yager, 2005); this may explain binging behavior. The positive

response of some clients with buli-mia to treatment with selective serotonin

reuptake inhibi-tor antidepressants supports the idea that serotonin levels at

the synapse may be low in these client

Developmental Factors

Two essential tasks of adolescence are the struggle to develop

autonomy and the establishment of a unique iden-tity. Autonomy, or exerting

control over oneself and the environment, may be difficult in families that are

overpro-tective or in which enmeshment

(lack of clear role bound-aries) exists. Such families do not support members’

efforts to gain independence, and teenagers may feel as though they have little

or no control over their lives. They begin to control their eating through severe

dieting and thus gain control over their weight. Losing weight becomes

reinforc-ing: by continuing to lose, these clients exert control over one

aspect of their lives.

It is important to identify potential risk factors for developing

eating disorders so that prevention programs can target those at greatest risk.

Adolescent girls who express body dissatisfaction are most likely to experience

adverse outcomes, such as emotional eating, binge eating, abnormal attitudes

about eating and weight, low self-esteem, stress, and depression.

Characteristics of those who developed an eating disorder included disturbed

eat-ing habits; disturbed attitudes toward food; eating in secret;

preoccupation with food, eating, shape, or weight; fear of losing control over

eating; and wanting to have a completely empty stomach (Cave, 2009).

The need to develop a unique identity, or a sense of who one is as

a person, is another essential task of adolescence. It coincides with the onset

of puberty, which initiates many emotional and physiologic changes. Self-doubt

and confu-sion can result if the adolescent does not measure up to the person

she or he wants to be.

Advertisements, magazines, and movies that feature thin models

reinforce the cultural belief that slimness is attractive. Excessive dieting

and weight loss may be the way an adolescent chooses to achieve this ideal. Body image is how a person perceives his or her body, that is, a mental self-image. For most people,

body image is consis-tent with how others view them. For people with anorexia

nervosa, however, body image differs greatly from the per-ception of others.

They perceive themselves as fat, unattractive, and undesirable even when they

are severely underweight and malnourished. Body

image disturbance occurs when there is an extreme discrepancy between one’s

body image and the perceptions of others and extreme dissatisfaction with one’s

body image.

Self-perceptions of the body can influence the devel-opment of

identity in adolescence greatly and often per-sist into adulthood.

Self-perceptions that include being overweight lead to the belief that dieting

is necessary before one can be happy or satisfied. Clients with bulimia nervosa

report dissatisfaction with their bodies as well as the belief that they are

fat, unattractive, and undesirable. The binging and purging cycle of bulimia

can begin at any time—after dieting has been unsuccessful, before the severe

dieting begins, or at the same time as part of a “weight loss plan.”

Family Influences

Girls growing up amid family problems and abuse are at higher risk

for both anorexia and bulimia. Disordered eating is a common response to family

discord. Girls growing up in families without emotional support often try to

escape their ![]()

![]() negative emotions. They place an intense focus

outward on something concrete: physical appearance. Disordered eating becomes a

distraction from emotions.

negative emotions. They place an intense focus

outward on something concrete: physical appearance. Disordered eating becomes a

distraction from emotions.

Childhood adversity has been identified as a significant risk

factor in the development of problems with eating or weight in adolescence or

early adulthood. Adversity is defined as physical neglect, sexual abuse, or

parental mal-treatment that includes little care, affection, and empathy as

well as excessive paternal control, unfriendliness, or overprotectiveness.

Sociocultural Factors

In the United States and other Western countries, the media fuels

the image of the “ideal woman” as thin. The culture equates beauty,

desirability, and, ultimately, hap-piness with being very thin, perfectly

toned, and physi-cally fit. Adolescents often idealize actresses and models as

having the perfect “look” or body even though many of these celebrities are

underweight or use special effects to appear thinner than they are. Books,

magazines, dietary supplements, exercise equipment, plastic surgery advertisements,

and weight loss programs abound; the dieting industry is a billion-dollar

business. The culture considers being overweight a sign of laziness, lack of

self-control, or indifference; it equates pursuit of the “perfect” body with

beauty, desirability, success, and will power. Thus, many women speak of being

“good” when they stick to their diet and “bad” when they eat desserts or

snacks.

Pressure from others also may contribute to eating dis-orders.

Pressure from coaches, parents, and peers and the emphasis placed on body form

in sports such as gymnas-tics, ballet, and wrestling can promote eating

disorders in athletes. Parental concern over a girl’s weight and teasing from

parents or peers reinforces a girl’s body dissatisfac-tion and her need to diet

or control eating in some way. Studies in the United States and Europe conclude

that bul-lying and peer harassment are also related to an increase in

disordered eating habits (Eisenberg & Neumark-Sztainer, 2008; Sweetingham

& Walter, 2008).

Related Topics