Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Onset and Clinical Course

Anorexia nervosa typically begins between 14 and 18 years of age.

In the early stages, clients often deny they have a neg-ative body image or

anxiety regarding their appearance. They are very pleased with their ability to

control their weight and may express this. When they initially come for

treatment, they may be unable to identify or to explain their emotions about

life events such as school or relationships with family or friends. A profound

sense of emptiness is common.

As the illness progresses, depression and lability in mood become more

apparent. As dieting and compulsive behaviors increase, clients isolate

themselves. This social isolation can lead to a basic mistrust of others and

even paranoia. Clients may believe their peers are jealous of their weight loss

and may believe that family and health care professionals are trying to make

them “fat and ugly.”

In long-term studies of clients with anorexia nervosa, Anderson and

Yager (2005) reported that 30% were well, 30% were partially improved, 30% were

chronically ill, and 10% had died of anorexia-related causes. Clients with the

lowest body weights and longest durations of illness tended to relapse most

often and have the poorest out-comes. Clients who abuse laxatives are at a

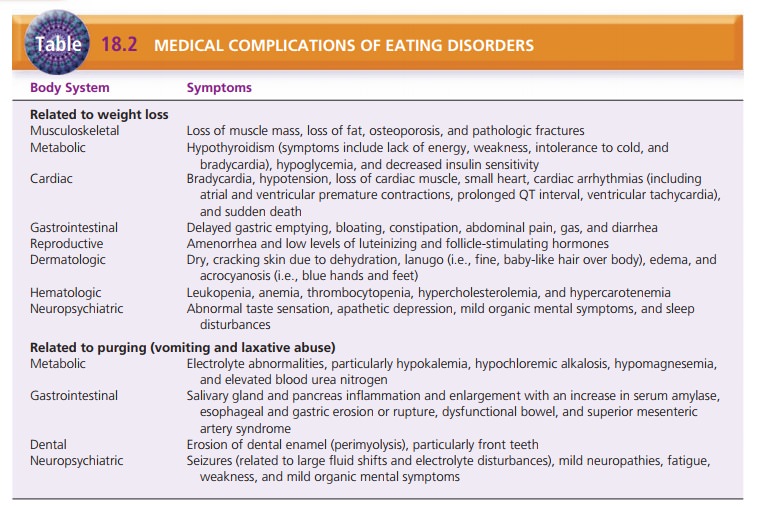

greater risk for medical complications. Table 18.2 lists common medical

complications of eating disorders.

Treatment and Prognosis

Clients with anorexia nervosa can be very difficult to treat

because they are often resistant, appear uninter-ested, and deny their

problems. Treatment settings include inpatient specialty eating disorder units,

partial hospitalization or day treatment programs, and outpa-tient therapy. The

choice of setting depends on the sever-ity of the illness, such as weight loss,

physical symptoms, duration of binging and purging, drive for thinness, body

dissatisfaction, and comorbid psychiatric conditions. Major life-threatening

complications that indicate the need for hospital admission include severe

fluid, electro-lyte, and metabolic imbalances; cardiovascular complica-tions;

severe weight loss and its consequences (Andreasen

Black, 2006); and risk for suicide. Short hospital stays are most

effective for clients who are amenable to weight gain, and gain weight rapidly

while hospitalized. Longer inpatient stays are required for those who gain

weight more slowly and are more resistant to gaining additional weight (Thiels,

2008). Outpatient therapy has the best success with clients who have been ill

for fewer than 6 months, are not binging and purging, and have parents likely

to participate effectively in family therapy. Cognitive behavior therapy can

also be effective in preventing relapse and improving overall outcomes.

Medical Management

Medical management focuses on weight restoration, nutri-tional

rehabilitation, rehydration, and correction of elec-trolyte imbalances. Clients

receive nutritionally balanced meals and snacks that gradually increase caloric

intake to a normal level for size, age, and activity. Severely malnour-ished

clients may require total parenteral nutrition, tube feedings, or

hyperalimentation to receive adequate nutri-tional intake. Generally, access to

a bathroom is supervised to prevent purging as clients begin to eat more food.

Weight gain and adequate food intake are most often the criteria for

determining the effectiveness of treatment.

Psychopharmacology

Several classes of drugs have been studied, but few have shown

clinical success. Amitriptyline (Elavil) and the anti-histamine cyproheptadine

(Periactin) in high doses (up to 28 mg/day) can promote weight gain in

inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) has been used with

success because of its antipsychotic effect (on bizarre![]()

![]() body image distortions) and associated weight

gain. Fluoxetine (Prozac) has some effectiveness in preventing relapse in

clients whose weight has been partially or com-pletely restored (Andreasen

& Black, 2006); however, close monitoring is needed because weight loss can

be a side effect.

body image distortions) and associated weight

gain. Fluoxetine (Prozac) has some effectiveness in preventing relapse in

clients whose weight has been partially or com-pletely restored (Andreasen

& Black, 2006); however, close monitoring is needed because weight loss can

be a side effect.

Psychotherapy

Family therapy may be beneficial for families of clients younger

than 18 years. Families who demonstrate enmesh-ment, unclear boundaries among

members, and difficulty handling emotions and conflict can begin to resolve

these issues and improve communication. Family therapy also is useful to help

members to be effective participants in the client’s treatment. However, in a

dysfunctional family, significant improvements in family functioning may take 2

years or more.

Individual therapy for clients with anorexia nervosa may be

indicated in some circumstances; for example, if the family cannot participate

in family therapy, if the client is older or separated from the nuclear family,

or if the cli-ent has individual issues requiring psychotherapy. Therapy that focuses

on the client’s particular issues and circum-stances, such as coping skills,

self-esteem, self-acceptance, interpersonal relationships, assertiveness, can

improve overall functioning and life satisfaction. Cognitive– behavioral

therapy (CBT), long used with clients with bulimia, has been adapted for

adolescents and used successfully (Schmidt, 2008).

Related Topics