Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Electroconvulsive Therapy

Electroconvulsive Therapy(ECT)

Indications

for ECT(Electroconvulsive Therapy)

General Considerations

In contrast

to its origins as a treatment of schizophrenia, ECT today is generally utilized

more frequently in patients with depression, es-pecially psychotic depression

and in the elderly. Mania and schizo-phrenia account for most of the remainder

of convulsive therapy use. The indications have been most clearly spelled out

by the American Psychiatric Association on ECT (American Psychiatric

Associa-tion, 1990, 2001), which identified “primary ” and “secondary” use of

convulsive therapy. Primary indications are those for which ECT may

appropriately be used as a first-line treatment. These include situations where

the patient’s medical or psychiatric condition re-quires rapid clinical

response, where the risk of alternative treat-ments is excessive, or where, based

on past history, response to ECT or nonresponse to medications is anticipated.

If these conditions are not met, medication or other alternative treatment is

recommended first, with ECT reserved for cases of nonresponse to adequate

trial(s), unacceptable adverse effects of the alternative treatment, or

deterio-ration of the patient’s condition, increasing the urgency of the need

for response (American Psychiatric Association, 2001). These gen-eral

principles in turn require individualized interpretation in the presence of

specific psychiatric and medical disorders. Even where ECT is not used as

treatment of first choice, its introduction sooner in the decision tree rather

than being reserved as a “last resort” may spare the patient multiple

unsuccessful medication trials, thereby avoiding months of suffering and

possibly reducing the likelihood of treatment resistance (American Psychiatric

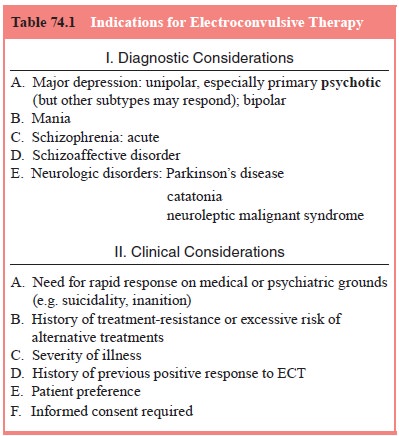

Association, 2001). Modern diagnostic and clinical considerations in the

recommenda-tion of ECT are summarized in Table 74.1.

ECT in Depression

It is

well established that major depression is a heterogeneous dis-order,

encompassing mildly ill, functioning outpatients, as well as profoundly

disturbed, dysfunctional, or often psychotic inpatients. Along this spectrum,

ECT appears higher in the treatment hier-archy for the more severe presenting

depression, usually defined by the presence of neurovegetative signs,

psychosis, or suicidality (Abrams, 1982; American Psychiatric Association,

2000, 2001).

While

there are no absolute rules, severely melancholic or psychotically depressed

patients are often appropriate candidates for ECT as treatment of first choice,

whereas more moderately ill individuals might not be considered for ECT until

adequate medication trials have failed.

Predictors of Response

The

literature describes an overall response rate to ECT of 75 to 85% in depression

(Crowe, 1984; O’Connor et al., 2001).

Efforts to delineate subtypes of depression particularly responsive to ECT have

yielded inconsistent results. ECT is most likely to be helpful in an acute

episode of severe depression of relatively brief duration (Rich et al., 1984). Combined data from two

simulated-ECT-controlled trials (Brandon et

al., 1984; Buchan et al., 1992)

identified the presence of delusions and psychomotor retardation as predictive

of preferential response.

Psychotic

depression, increasingly recognized as a distinct subtype of mood disorder that

responds poorly to antidepressants alone, has emerged as a powerful indication

for ECT (Potter et al., 1991;

Petrides et al., 2001). In this

subgroup, ECT is at least as effec-tive as a combination trial of

antidepressant and antipsychotic med-ications. On balance, the evidence

supports the early use of ECT in psychotic depression, particularly in lieu of

prolonged, complicated medication trials that may be poorly tolerated,

especially in the el-derly (Khan et al.,

1987; Potter et al., 1991; Sackeim,

1993).

While bipolar (discussed below) and unipolar depressions are equally responsive to ECT (American Psychiatric Associa-tion, 2002), response may be less likely with secondary than primary depression, in both adults (Kramer, 1982; Zorumski et al., 1986; Zimmerman et al., 1986a), including the elderly

Bipolar Disorder

ECT is an

extremely effective and rapidly acting treatment for both acute mania and

bipolar depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2002). However, it is

infrequently used for mania, because of the availability of pharmacological

strategies. Nonetheless, ECT has been repeatedly endorsed as an accepted

second- or third-line treatment for acute manic episodes, particularly in cases

of medication resistance, in patients of all ages (NIH/NIMH, 1985; Goodwin and

Jamison, 1990; Mukherjee et al.,

1994; Van Gerpen et al., 1999;

American Psychiatric Association,

2002). In medical emergencies associated with mania, ECT can be regarded as a

treatment of first choice (American Psychiatric Association, 2002). The same is

true for medical conditions accompanying acute mania (including pregnancy,

discussed later) that contraindicate or render intolerable the use of

psychotropic medications.

There is

little information on which manic patients benefit most from ECT or on optimal

ECT treatment in mania. Bipolar depression responds as well as unipolar

depression to ECT, in both adult and geriatric patients (American Psychiatric

Association, 2002). Hypomania or mania is a risk of using ECT for depression in

bipolar patients, but this is not different from the experience with any

antidepressant treatment in this disorder (Gormley et al., 1998; American Psychiatric Association, 2001, 2002).

Schizophrenia

Among the

changes undergone by convulsive therapy over its 60-year history, few are as

striking as those associated with its use in chronic psychotic illness. ECT has

evolved from a treatment of first choice to often a treatment of last resort

for DSM-IV schizo-phrenia. However, the efficacy of ECT for depressive symptoms

associated with psychotic illness is reflected in recent nationwide data

showing the use of convulsive therapy in almost 12% of patients with recurrent

major depression comorbid with schizo-phrenia (Olfson et al., 1998), a utilization rate higher than that seen in

uncomplicated recurrent depressive disorder.

The

American Psychiatric Association Task Force on ECT (American Psychiatric

Association, 2001) and the Canadian Psy-chiatric Association (Enns and Reiss,

1992) identified a role for ECT as a second-line treatment for selected

patients with schizo-phrenia, particularly when associated with a brief

duration of ill-ness and/or affective symptoms.

It has

been consistently found that the schizophrenic patients most likely to respond

to ECT are those with good prognosis signs: mood disturbances, short duration

of illness, predominance of positive rather than negative symptoms, and

overexcitement (Fink and Sackeim, 1996). The potential respon-siveness of acute

psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia to ECT is more emphatically stated in the

2001 revision of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report

compared with the previous edition, based on research conducted and compiled in

the intervening decade (Fink and Sackeim, 1996).

Other Axis I Disorders

As

reiterated in the Surgeon General’s report on mental health (US Department of

Health and Human Services, 1999), ECT has no demonstrated efficacy in

dysthymia, substance abuse, or anxi-ety disorder. Nonetheless, ECT may play a

role when the sever-ity of a secondary major depression is severe and/or treatment

refractory (American Psychiatric Association, 2001). In such cir-cumstances,

ECT can be expected to improve the comorbid mood component, leaving the

underlying primary disorder untreated; in some circumstances, removal of the

burden of overlying de-pression may indirectly benefit the underlying disorder.

In the face of a potentially ECT-responsive major depressive episode, the

presence of a nonmood Axis I disorder, even substance abuse, should not

constitute a contraindication to the use of convulsive therapy (Olfson et al., 1998; American Psychiatric

Association, 2001).

Axis II Disorders

There are

no evidence-based biological treatments for DSM-IV Axis II personality

disorders, including ECT. Given the high incidence of comorbid, often

treatment-refractory depression that accompanies Axis II pathology, ECT has

been used in per-sonality disordered patients, with inconsistent – but

generally negative – reports of success, for many years.

Neurologic Disorders

Only 1%

of patients admitted with a primary diagnosis other than a mood disorder or

schizophrenia are treated with ECT in this country (Thompson et al., 1994). Nonetheless, individuals

with neurologic or other medical problems often suffer from primary or secondary

mood or motor disorders that are ECT-responsive.

Catatonia

Over the

past decade, benzodiazepines have emerged as the phar-macological treatment of

choice for catatonia (Rosebush et al.,

1992; Ungavari et al., 1994).

However, in medication-unrespon-sive patients, prolonged drug trials with

continuing clinical de-terioration can be avoided in favor of a course of ECT

(Ungavari et al., 1994). Reflecting

current understanding of the syndrome and

its treatment, Fricchione (1989) recommended that “given the significant

morbidity and mortality associated with catatonia, ECT should be considered if

an expeditious 48- to 72-hour ben-zodiazepine trial is unsuccessful”. As a

practical point, given the now-common initial use of benzodiazepines in this

condition, the catatonic patient may come to ECT with an initially elevated

seizure threshold, and treatment parameters should be adjusted accordingly

(Fink, 2002).

Other Neurologic Illness

The

remaining neurological indications for ECT can be consid-ered to fall into two

major categories: 1) those for which, as with any medical illness, ECT is

considered for treatment of a sec-ondary depression when benefit–risk analysis

favors ECT over antidepressant medications and 2) those for which ECT may play

a special role by virtue of its unique actions compared with alter-native

treatment options.

In the

first category are such conditions as poststroke depression (Murray et al., 1986; Currier et al., 1992) and mood disturbance in

the context of brain trauma, tumor, or dementia (Hsiao et al., 1987; Liang et al.,

1988; Kohler and Burock, 2001). Medication may be difficult to tolerate by

these neurologically ill patients, tilting the potential benefit–risk ratio in

favor of ECT (Price and McAllister, 1989).

Potential

contraindications to ECT are very few and rarely are absolute (American

Psychiatric Association, 2001). Although ECT generally should not be performed

in the pres-ence of raised intracranial pressure, it has been given safely even

in the face of brain tumors and other mass lesions (Hsiao et al., 1987; Fried and Mann, 1988; Abrams, 1991; Kohler and Burock, 2001) with special steps taken

to protect against the ECT-associated hemodynamic changes; intracranial

pres-sure may be reduced with the use of oral or parenteral steroids (Beale et al., 1997).

Other Considerations in the Use of ECT

It can be

appreciated that while accurate psychiatric diagno-sis is essential to

prioritize treatment options, it is far from the only consideration for the

clinician weighing the advantages and potential problems of prescribing ECT

(American Psychiatric Association, 2001). Two often-related variables are the

patient’s state of physical health and age. A large number of individuals

receiving ECT in this country are elderly, many of whom are physically

compromised.

Two

general points should be made about the use of ECT in the elderly: 1) the

physiological changes associated with ECT – cardiovascular (elevated blood

pressure, arrhythmias), cognitive (confusion, memory loss), risk of traumatic

injury to bones and teeth – that are benign and easily tolerated in young and

middle-aged patients are prominent sources of potential ECT-associated

morbidity in geriatric patients, and 2) the safety of ECT is appreciably

enhanced if the foregoing effects on the older body, whether healthy or

diseased, are anticipated and con-trolled. For example, Casey and Davis (1996)

noted that a “rigor-ous falls prevention protocol” helped protect their elderly

ECT patients from a potentially dangerous complication seen in ear-lier studies

The very

limited use of modern ECT in young people is generally reserved for cases of

depression or mania complicated by medication resistance or the need for an

urgent clinical re-sponse. Nonetheless, where ECT is utilized in younger

patients, its efficacy and safety appear comparable to those in adults (Rey and

Walter, 1997; Cohen et al., 2000).

A special

physical health challenge to the treatment of mental disorders is presented by

pregnancy. Guidelines for the administration of ECT in the pregnant patient,

incorporating measures such as intravenous hydration, avoidance of

hyperven-tilation and nonessential anticholinergic medication, measures against

gastric reflux, proper positioning of the patient during treatment, and uterine

and fetal cardiac monitoring, have been developed and incorporated into modern

practice (American Psychiatric Association, 2001).

Pretreatment Evaluation

Once the

decision has been made to proceed with a course of ECT, specific steps are

taken by the treatment team to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks. In

some instances these pro-cedures are part of the initial work-up, and the

results may influ-ence treatment decisions, as when certain psychiatric or

physical disorders are ruled in or out.

The

psychiatrist will want to make use of appropriate consultants, especially

representing the fields of anesthesiol-ogy and, when indicated, internal

medicine (often cardiology) or obstetrics. Given the current regulatory

climate, the physician needs to be aware of local requirements regarding the

need for second opinions or other pretreatment procedures in certain

cir-cumstances, or to arrange for guardianship or court proceedings where the

patient’s capacity to consent to ECT is in question, to assure that the

initiation of treatment is not unduly delayed.

Psychiatric Considerations

The

pre-ECT evaluation is a good time to confirm psychiatric diagnosis, including

Axis II and III. In many settings, a specific ECT consultation may be helpful

in evaluating the patient for a potentially ECT-responsive disorder and

weighing the various treatment options (Klapheke, 1997). Input from nursing and

other professional staff that have been working with the patient should be

factored in. Should the indications for ECT remain present, baseline

assessments of mental status including evaluation of suicidality, orientation

and memory will help monitor changes in both therapeutic and adverse effects

over the course of treatment. The history and effects of previous treatment

with ECT should be obtained. Also, this time, decisions must be made regarding

ongoing psychotropic medications particularly those increasing the risk of

toxicity in combination with ECT, for example lithium and those affecting

seizure threshold, such as benzodiazepines and anticonvulsants – and steps

instituted to adjust, taper, or dis-continue these medications, when

appropriate.

Other Medical Considerations

History and physical examination should focus on the cardiovas-cular and neurological systems, the areas of greatest risk. The consulting internist, anesthesiologist, or other physician should advise the treatment team regarding cardiovascular risk of ECT and the need for any modifications in treatment technique, such as medications to moderate hemodynamic changes (Dolinski and Zvara, 1997). Appropriate pretreatment optimization and moni toring of medical conditions that may be affected by ECT, such as diabetes, should be arranged at this time.

In the

uncomplicated situation, the routine laboratory work-up for ECT is that

indicated for any procedure involving general anesthesia: complete blood count,

serum electrolyte levels and electrocardiogram (ECG)

(American Psychiatric

Association, 2001; Chaturvedi et al., 2001). Chest X-ray is often obtained as

well. The need for further pretreatment work-up, such as serum chemistries,

urinalysis, HIV antibody titers and medication blood concentrations, is

determined on an individual basis (Lafferty et al., 2001). Given a normal

neurologic and fundoscopic examination, computerized tomography (CT) or

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is not indicated.

Lumbosacral

spine films, historically routine prior to institution of muscle relaxation in

the ECT premedication protocol, have become optional for many patients. This

remains appropriate for older patients with a history of or at risk for

osteoporosis, and for any patient with a history of bone trauma. A formal

anesthesiology consultation should result in an assignment of the degree of

anesthesia risk and recommendations for any necessary modification in the ECT

protocol (Folk et al., 2000). A personal or family history of anesthesia

complications may call for special assessment. The condition of dentition

should be routinely assessed to avoid the treatment-associated risk of

aspiration or fracture of loose teeth or bridgework.

Informed Consent

Among the

unique features of ECT compared with other standard psychiatric treatments is

the requirement for written informed consent by the patient or legal guardian

or other substitute. Guidelines regarding the content of a standard informed

consent form for ECT have been published (American Psychiatric Asso-ciation,

2001). Supplemental information regarding ECT for pa-tients and their families

in a variety of media is also available and its distribution is encouraged

(Fink, 1999; American Psychiatric Association, 2001).

The

NIH/NIMH Consensus Development Conference on ECT (1985) emphasized that

informed consent is a process that continues throughout the treatment course.

Given the transient cognitive impairments common in depression and during an

ECT course, it is particularly necessary to maintain a dialogue with the

patient as treatment progresses to assure that all of the patient’s questions

and concerns are addressed, even if repetitive discourse ensues. With

appropriate modification of the presenta-tion of information, including use of

nonverbal demonstration of the procedure, even patients with mental retardation

often can make informed decisions about consent for ECT (Van Waarde et al., 2001).

Related Topics