Chapter: Business Science : Business Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance : Environmental Ethics

Economic grow - implications for business

Friedman

and the defense of “unrealistic assumptions”

Although some contemporary

philosophers have argued that Mill's method a priori is largely defensible

(Bhaskar 1978, Cartwright 1989, and Hausman 1992), by the middle of the

Twentieth Century Mill's views appeared too many economists out of step with

contempo rary philosophy of science. Without studying Mill's text carefully, it

was easy for economists to misunderstand his terminology and to regard his

method a priori as opposed to empiricism. Others took seriously Mill's view

that the basic principles of economics should be empirically established and

found evidence to cast doubt on some of the basic principles, particularly the

view that firms attempt to maximize profits (Hall and Hitch 1938, Lester 1946,

1947). Methodologists who were well- informed about contemporary developments

in philosophy of science, such as Terence Hutchison (1938), denounced

―pure theory‖ in economics as

unscientific.

Philosophically reflective

economists proposed several ways to replace the old- fashioned Millian view

with a more up-to-date methodology that would continue to justify much of

current practice (see particularly Machlup 1955, 1960 and Koopmans 1957). By

far the most influential of these was Milton Friedman's contribution in his

1953 essay, ―The Methodology of Positive Economics.‖ This essay has had an

enormous influence, far more than any other work on methodology.

Friedman begins his essay by

distinguishing in a conventional way between positive and normative economics

and conjecturing that policy disputes are typically really disputes about the

consequences of alternatives and can thus be resolved by progress in positive

economics. Turning to positive economics, Friedman asserts (without argument)

that correct prediction concerning phenomena not yet observed is the ultimate

goal of all positive sciences. He holds a practical view of science and looks

to science for predictions that will guide policy.

Since it is difficult and often

impossible to carry out experiments and since the uncontrolled phenomena

economists observe are difficult to interpret (owing to the same causal

complexity that bothered Mill), it is hard to judge whether a particular theory

is a good basis for predictions or not. Consequently, Friedman argues,

economists have supposed that they could test theories by the realism of their

―assumptions‖ rather than by the accuracy of their predictions. Friedman argues

at length that this is a grave mistake. Theories may be of great predictive

value even though their assumptions are extremely ―unrealistic.‖ The realism of

a theory's assumptions is, he maintains, irrelevant to its predictive value. It

does not matter whether the assumption that firms maximize profits is

realistic. Theories should be appraised exclusively in terms of the accuracy of

their predictions. What matters is whether the theory of the firm makes correct

and significant predictions.

As critics have pointed out (and

almost all commentators have been critical), Friedman refers to several

different things as ―assumptions‖ of a theory and means several different

things by speaking of assumptions as ―unrealistic‖ (Brunner 1969). Since Friedman

aims his criticism to those who investigate empirically whether firms in fact

attempt to maximize profits, he must take

―assumptions‖ to include central

economic generalizations, such as ―Firms attempt to maximize profits,‖ and by

―unrealistic,‖ he must mean, among other things, ―false.‖ In arguing that it is

a mistake to appraise theories in terms of the realism of assumptions, Friedman

is arguing at least that it is a mistake to appraise theories by investigating

whether their central generalizations are true or false.

It would seem that this

interpretation would render Friedman's views inconsistent, because in testing

whether firms attempt to maximize profits, one is checking whether predictions

of theory concerning the behavior of firms are true or false. An ―assumption‖

such as ―firms maximize profits‖ is itself a prediction. But there is a further

wrinkle. Friedman is not concerned with every prediction of economic theories.

In Friedman's view, ―theory is to be judged by its predictive power for the class of phenomena which it is

intended to explain” (1953, p. 8). Economists are interested in only some of the implications of economic theories.

Other predictio ns, such as those concerning the results of surveys of

managers, are irrelevant to policy. What matters is whether economic theories

are successful at predicting the phenomena that economists are interested in.

In other words, Friedman believes that economic theories should be appraised in

terms of their predictions concerning prices and quantities exchanged on

markets. In his view, what matters is

―narrow predictive success‖ (Hausman

2008a), not overall predictive adequacy.

So economists can simply ignore the

disquieting findings of surveys. They can ignore the fact that people do not

always prefer larger bundles of commodities to smaller bundles of commodities.

They need not be troubled that some of their models suppose that all agents

know the prices of all present and future commodities in all markets. All that

matters is whether the predictions concerning market phenomena turn out to be

correct. And since anomalous market outcomes could be due to any number of

uncontrolled causal factors, while experime nts are difficult to carry out, it

turns out that economists need not worry about ever encountering evidence that

would disconfirm fundamental theory. Detailed models may be confirmed or

disconfirmed, but fundamental theory is safe. In this way one can understand

how Friedman's methodology, which appears to justify the eclectic and pragmatic

view that economists should use any model that appears to ―work‖ regardless of

how absurd or unreasonable its assumptions might appear, has been deployed in

service of a rigid theoretical orthodoxy.

Rational

choice theory

Insofar as economics explains and

predicts phenomena as consequences of individual choices, which are they

explained in terms of reasons, it must depict agents as to some extent

rational. Rationality, like reasons, involves evaluation, and just as one can

assess the rationality of individual choices, so one can assess the rationality

of social choices and examine how they are and ought to be related to the

preferences and judgments of individuals. In addition, there are intricate

questions concerning rationality in strategic situations in which outcomes

depend on the choices of multiple individuals. Since rationality is a central

concept in branches of philosophy such as action theory, epistemology, ethics,

and philosophy of mind, studies of rationality frequently cross the boundaries

between economics and philosophy.

Individual

rationality

The barebones theory of rationality

discussed above in Section 1.1 takes an agent's preferences (rankings of

objects of choice) to be rational if they are complete and transitive, and it

takes the agent's choice to be rational if the agent does not prefer any

feasible alternative to what he or she chooses. Such a theory of rationality is

clearly too weak, because it says nothing about belief or what rationality

implies when agents do not know (with certainty) everything relevant to their

choices. But it may also be too strong, since, as Isaac Levi in particular has

argued (1986), there is nothing irrational about having incomplete preferences

in situations involving uncertainty. Sometimes it is rational to suspend

judgment and to defer ranking alternatives that are not well understood. On the

other hand, transitivity is a plausible condition, and the so-called ―money

pump‖ argument demonstrates that if one's preferences are intransitive and one

is willing to make exchanges, then one can be exploited. (Suppose an agent A

prefers X to Y, Y to Z and Z to X, and that A will pay some small amount of

money $P to exchange Y for X, Z for Y, and X for Z. That means that, starting

with Z, A will pay $P for Y, then $P again for X, then $P again for Z and so

on. Agents are not this stupid. They will instead refuse to trade or adjust

their preferences to eliminate the intransitivity (but see Schick 1986).

On the other hand, there is

considerable experimental evidence that people's preferences are not in fact

transitive. Such evidence does not establish that transitivity is not a

requirement of rationality. It may show instead that people are sometimes

irrational. In the case of so-called

―preference reversals,‖ for example,

it seems plausible that people in fact make irrational choices

(Lichtenstein and Slovic 1971,

Tversky and Thaler 1990). Evidence of persistent violations of transitivity is

disquieting, since standards of rationality should not be impossibly high.

.

Collective

rationality and social choice

Although societies are very

different from individuals, they evaluate alternatives and make choices, which

may be rational or irrational. It is not, however, obvious, what principles of

rationality should govern the choices and evaluations of society. Transitivity

is one plausible condition. It seems that a society that chooses X when faced

with the alternatives X or Y, Y when faced with the alternatives Y or Z and Z

when faced with the alternatives X or Z either has had a change of heart or is

choosing irrationally. Yet, purported irrationalities such as these can easily

arise from standard mechanisms that aim to link social choices and individual

preferences. Suppose there are three individuals in the society. Individual One

ranks the alternatives X, Y, Z. Individual Two ranks them Y, Z, X. Individual

Three ranks them Z, X, Y. If decisions are made by pairwise majority voting, X

will be chosen from the pair (X, Y), Y will be chosen from (Y, Z), and Z will

be chosen from (X, Z). Clearly this is unsettling, but is possible cycles in

social choices irrational?

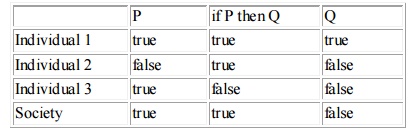

Similar problems affect what one

might call the logical coherence of social judgments (List and Pettit 2002).

Suppose society consists of three individuals who make the following judgments

concerning the truth or falsity of the propositions P and Q and that social

judgment follows the majority.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The judgments of each of the individuals are consistent with

the principles of logic, while social judgments violate them. How important is

it that social judgments be consistent with the principles of logic?

The judgments of each of the individuals are consistent with

the principles of logic, while social judgments violate them. How important is

it that social judgments be consistent with the principles of logic?

Although social choice theory in

this way bears on questions of social rationality, most work in social choice

theory explores the consequences of principles of rationality coupled with

explicitly ethical constraints. The

seminal contribution is Kenneth Arrow's impossibility theorem (1963, 1967). Arrow assumes that both

individual preferences and social choices are complete and transitive and (as

completeness implies) that the method of making social choices issues in some

choice for any possible profile of individual preferences. In addition, he

imposes a weak unanimity condition: if everybody prefers X to Y, then Y must

not be chosen. Third, he requires that there be no dictator whose preferences

determine social choices irrespective of the preferences of anybody else.

Lastly, he imposes the condition that the social choice between X and Y should

depend on how individuals rank X and Y and on nothing else. Arrow then proved

the surprising result that no method of relating social choices and individual

preferences can satisfy all these conditions!

In the sixty years since Arrow

wrote, there has been a plethora of work in social choice theory, a good deal

of which is arguably of great importance to ethics. For example, John Harsanyi

proved that if individual preferences and social evaluations both satisfy the

axioms of expected utility theory (with shared or objective probabilities) and

a stronger unanimity condition is imposed, then social evaluations are

determined by a weighted sum of individual utilities (1955, 1977a). Matthew

Adler (2012) has recently extended an approach like Harsanyi's to demonstrate

that a form of weighted utilitarianism, which prioritizes the interests of

those who are worse off, uniquely satisfies a longer list of rational and

ethical constraints. When there are instead disagreements in probability

assignments, there is an impossibility result: the unanimity condition implies

that social evaluations will not satisfy the axioms of expected utility theory

(Hammond 1983, Seidenfeld, et al. 1989, Mongin 1995). For further discussion of

social choice theory and the relevance of utility theory to social evaluation,

see Sen (1970) and for recent reappraisals Fleurbaey (2007) and Adler (2012).

Game

theory

When outcomes depend on what several

agents do, one agent's best choice may depend o n what other agents choose. Although

the principles of rationality governing individual choice still apply, arguably

there are further principles of rationality governing e xpectations of the

actions of others (and of their expectations concerning your actions and

expectations, and so forth). Game theory occupies an increasingly important

role within economics itself, and it is also relevant both to inquiries

concerning rationality and inquiries concerning ethics. For further discussion

see the entries on Game Theory, Game Theory and Ethics, and Evolutionary Game

Theory.

Economics

and ethics

As discussed above in Section 2.1 most economists distinguish between positive and normative

economics, and most would argue that economics is mainly relevant to policy

because of the (positive) information it provides concerning the consequences

of policy. Yet the same economists also offer their advice concerning how to

fix the economy. In addition, there is a whole field of normative economics.

Economic outcomes, institutions, and

processes may be better or worse in several different ways. Some outcomes may

make people better off. Other outcomes may be less unequal. Others may restrict

individual freedom more severely. Economists typically evaluate outcomes

exclusively in terms of welfare. This does not imply that they believe that

only welfare is of moral importance. They focus on welfare, because they

believe that economics provides a particularly apt set of tools to address

questions of welfare and because they believe or hope that questions about

welfare can be separated from questions about equality, freedom, or justice. As

sketched below, economists have had some things to say about other dimensions

of moral appraisal, but welfare takes center stage. Indeed normative economics

is often called ―welfare economics.‖

Welfare

One central question of moral

philosophy has been to determine what things are intrinsically good for human

beings. This is a central question, because all plausible moral views assign an

important place to individual welfare or well-being.

This is obviously true of

utilitarianism (which hold that what is right maximizes total or average

welfare), but even non-utilitarian views must be concerned with welfare, if

they recognize the virtue of benevolence, or if they are concerned with the

interests of individuals or with avoiding harm to individuals.

There are many ways to think about

well-being, and the prevailing view among economists themselves has shifted

from hedonism (which takes the good to be a mental state such as pleasure or

happiness) to the view that welfare can be measured by the satisfaction of

preferences.

Efficiency

Because the identification of

welfare with preference satisfaction makes it questionable whether one can make

interpersonal welfare comparisons, few economists defend a utilitarian view of

policy as maximizing total or average welfare. (Harsanyi is one exception, for

another see Ng 1983). Economists have instead explored the possibility of

making welfare evaluations of economic processes, institutions, outcomes, and

policies without making interpersonal comparisons. Consider two economic

outcomes S and R, and suppose that some people prefer S to R and that nobody

prefers R to S. In that case S is ―Pareto superior‖ to R, or S is a ―Pareto

improvement‖ over R. Without making any interpersonal comparisons, one can

conclude that people's preferences are better satisfied in S than in R. If

there is no state of affairs that is Pareto superior to S, then economists say

that S is ―Pareto optimal‖ or ―Pareto efficient.‖ Efficiency here is efficiency

with respect to satisfying preferences rather than minimizing the number of

inputs needed to produce a unit of output or some other technical notion

(Legrand 1991). If a state of affairs is not Pareto efficient, then society is

missing an opportunity costlessly to satisfy some people's preferences better.

A Pareto efficient state of affairs avoids this failure, but it has no other

obvious virtues. For example, suppose nobody is satiated and people care only

about how much food they get. Consider two distributions of food. In the first,

millions are starving but no food is wasted. In the second, nobody is starving,

but some food is wasted. The first is Pareto e fficient, while the second is

not.

Other

directions in normative economics

Although welfare economics and

concerns about efficiency dominate normative economics, they do not exhaust the

subject, and in collaboration with philosophers, economists have made various

important contributions to contemporary work in ethics and normative social and

political philosophy. Section 5.2 and Section 5.3 gave some hint of the

contributions of social choice theory and game theory. In addition economists

and philosophers have been working on the problem of providing a formal

characterization of freedom so as to bring tools of economic analysis to bear

(Pattanaik and Xu 1990, Sen 1988, 1990, 1991, Carter 1999). Others have

developed formal characterizations of equality of resources, opportunity, and

outcomes and have analyzed the conditions under which it is possible to

separate individual and social responsibility for inequalities (Pazner and

Schmeidler 1974, Varian 1974, 1975, Roemer 1986b, 1987, Fleurbaey 1995, 2008).

John Roemer has put contemporary economic modeling to work to offer precise

characterizations of exploitation (1982). Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum have

not only developed novel interpretations of the proper concerns of normative

economics in terms of capabilities (Sen 1992, Nussbaum and Sen 1993, Nussbaum

2000), which Sen has linked to characterizations of egalitarianism and to

operational measures of deprivation (1999). There are many lively interactions

between normative economics and moral philosophy. See also the entries on

Libertarianism, Paternalism, Egalitarianism, and Economic Justice.

Conclusions

The frontiers between economics and

philosophy concerned with methodology, rationality, ethics and normative social

and political philosophy are buzzing with activity. This activity is diverse

and concerned with very different questions. Although many of these are

related, philosophy of economics is not a single unified enterprise. It is a

collection of separate inquiries linked to one another by connections among the

questions and by the dominating influence of mainstream economic models and

techniques.

Main Features of a Planned Economy

If we have a look at the planned economies, say, Russian, Chinese or even

Indian economy, we shall discover some characteristics. The formulation of the

plan and its implementation call for a certain type of economic and

administrative organization and a certain type of endeavor and set- up. It is

only natural, therefore, that the planned economies reveal some common

features.

Existence of a Central Planning

Authority

Related Topics