Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Sebaceous and sweat gland disorders

Eccrine sweat glands

Sweat

glands

Eccrine

sweat glands

There

are 2 –3 million sweat glands distributed all over the body surface but they

are most numerous on the palms, soles and axillae. The tightly coiled glands lie

deep in the dermis, and the emerging duct passes to the surface by penetrating

the epidermis in a corkscrew fashion. Sweat is formed in the coiled gland by

active secretion, involving the sodium pump. Some damage occurs to the membrane

of the secret-ory cells during sweating. Initially sweat is isotonic with

plasma but, under normal conditions, it becomes hypotonic by the time it is

discharged at the surface, after the tubular resorption of electrolytes and

water under the influence of aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone.

In

some ways the eccrine sweat duct is like a renal tubule. The pH of sweat is

between 4.0 and 6.8; it contains sodium, potassium chloride, lactate, urea and

ammonia. The concentration of sodium chloride in sweat is increased in cystic

fibrosis, and sweat can be analysed when this is suspected.

Sweat

glands have an important role in temperature control, the skin surface being

cooled by evaporation. Up to 10 L/day of sweat can be excreted. Three stim-uli

induce sweating.

1 Thermal

sweating is a reflex response to a raisedenvironmental temperature

and occurs all over the body, especially the chest, back, forehead, scalp and

axillae.

2 Emotional sweatingis

provoked by fear or anxietyand is seen mainly on the palms, soles and axillae.

3 Gustatory sweatingis

provoked by hot spicy foodsand affects the face.

The

eccrine sweat glands are innervated by cholinergic fibres of the sympathetic

nervous system. Sweating can therefore be induced by cholinergic, and blocked

by anticholinergic drugs. Central control of sweating resides in the preoptic

hypothalamic sweat centre.

Clinical

disorders can follow increased or decreased sweating, or blockage of sweat

gland ducts.

Generalized hyperhidrosis

Thermal hyperhidrosis

The

‘thermostat’ for sweating lies in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus.

Sweating follows any rise in body temperature, whether this is caused by

exercise, environmental heat or an illness. The sweating in acute infections,

and in some chronic illnesses (e.g. Hodgkin’s disease), may be a result of a

lowering of the ‘set’ of this thermostat.

Other causes of general hyperhidrosis

•

Emotional stimuli, hypoglycaemia,

opiate with-drawal, and shock cause sweating by a direct or reflex stimulation

of the sympathetic system at hypothalamic or higher centres. Sweating

accompanied by a general sympathetic discharge occurs on a cold pale skin.

•

Lesions of the central nervous

system (e.g. a cerebral tumour or cerebrovascular accident) can cause

gener-alized sweating, presumably by interfering directly with the hypothalamic

centre.

• Phaeochromocytoma, the carcinoid syndrome, dia-betes mellitus, thyrotoxicosis, Cushing’s syndrome and the hot flushes of menopausal women have all been associated with general sweating. The mechan-isms are not clear.

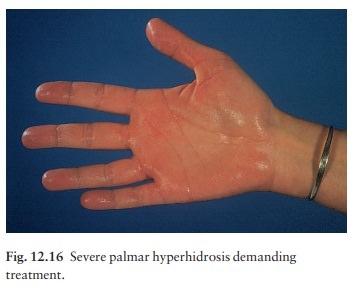

Local hyperhidrosis (Fig.

12.16)

Local hyperhidrosis plagues many young adults. The most common areas to be affected are the palms, soles and axillae. Too much sweating there is embarrassing, if not socially crippling.

A sodden shirt in contact with a dripping armpit, a wet

handshake and stinking feet are hard crosses to bear. Seldom is any cause

found, but organic disease, especially thyrotoxicosis, acromegaly, tuberculosis

and Hodgkin’s disease should be considered. A blatant anxiety state is

occasionally present, but more often an otherwise normal person is

understandably concerned about his or her antisocial condition. A vicious

circle emerges, in which increased anxiety drives further sweating.

These

problems may be no more than one end of the normal physiological range. How

many students sitting examinations have to dry their hands before putting pen

to paper? It is only when the sweating is gross, or continuous, that medical

advice is sought. Such sweating is often precipitated by emotional stimuli and

stops during sleep.

Treatment

Topical

applications. The most useful preparation foraxillary hyperhidrosis is

20% aluminium chloride hexahydrate in an alcohol base. At first it is applied

to the dry axillae every night. Soon the interval can be increased, and many

need the preparation only once or twice a week. The frequency may have to be

cut down if the preparation irritates the skin, which is most likely if it is

applied after shav-ing or when the skin is wet. Aluminium chloride also helps

hyperhidrosis of the palms and soles, but it is less effective there.

Potassium

permanganate soaks (1 : 10 000 aqueous solution) combat the bacterial

superinfection of sweaty feet that is responsible for their foul smell.

Patients should soak their feet for 15 min twice a day until the smell has

improved and be warned that potassium permanganate stains the skin and

everything else brown. Occasionally glutaraldehyde solutions are used instead,

but allergy and yellow-stained skin are potential com-plications. Topical

clindamycin is also effective.

Iontophoresis.

This is the passage of a low-voltagedirect current across

the skin. Iontophoresis with tap water or with the anticholinergic drug

glycopyrro-nium bromide (glycopyrolate, USA) may help palmar or plantar

hyperhidrosis. Patients attend two or three times a week for treatment until

the condition improves. Repeated courses or maintenance therapy may be

required.

Botulinum

toxin. This binds to presynaptic nervemembranes and then inhibits

the release of acetyl-choline. It is now the treatment of choice for severe

axillary or plantar hyperhidrosis, unresponsive to medical measures. Subdermal

aliquots of the toxin are injected into the hyperhidrotic area of the axilla or

sole, one region at a single session. Sweating is abolished after a delay of

2–3 days. Repeat injections (about every eighth month) are necessary as the

sweating returns when the toxin has gone. Antibodies may form against the toxin

and diminish its long-term effectiveness. Botulinum toxin is used less often

for palmar hyperhidrosis because of the risk of paralys-ing the intrinsic

muscles of the hand.

Systemic

treatment. Oral anticholinergic agents suchas Pro-Banthine and

glycopyronium bromide (USA) are sometimes tried but their side-effects limit

their value.

Surgery.

This is used less nowadays as the abovemeasures are usually effective. However,

recalcitrant axillary hyperhidrosis can be treated by removing the vault of the

axilla, which bears most of the sweat glands. These can be identified

preoperatively by apply-ing starch and iodine, which interact with sweat to

colour the sweat gland openings blue. Thoracoscopic sympathetic trunkotomy

(between the first and sec-ond thoracic ganglia) is effective for severe palmar

hyperhidrosis alone but is a last resort.

Hypohidrosis and anhidrosis

Anhidrosis caused by abnormality of the sweat glands

Heat

stroke. Caused by sweat gland exhaustion, thisis a medical

emergency seen most often in elderly

people

moving to a hot climate. It can also occur in the young, during or after

prolonged exercise, especially in hot climates. Patients present with

hyperthermia, dry skin, weakness, headache, cramps and confusion, leading to

vomiting, hypotension, oliguria, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalaemia, delirium

and death. They should be cooled down immediately with cold water, and fluids

and electrolytes must be replaced.

Hypohidrotic

ectodermal dysplasia. This rare disor-der is inherited

as an X-linked recessive trait, in which the sweat glands are either absent or

decreased. Affected boys have a characteristic facial appearance, with poor

hair and teeth (Figs 13.13 and 13.14), and are intolerant of heat.

Prematurity.

The sweat glands function poorly inpremature babies nursed in incubators and

hot nurseries.

Anhidrosis caused by abnormalities of the nervous system

Anhidrosis

may follow abnormalities anywhere in the sympathetic system, from the

hypothalamus to the peripheral nerves. It can therefore be a feature of multiple

sclerosis, a cerebral tumour, trauma, Horner’s syndrome or peripheral

neuropathy (e.g. leprosy, alcoholic neuropathy and diabetes). Patients with

widespread anhidrosis are heat-intolerant, develop-ing nausea, dizziness,

tachycardia and hyperthermia in hot surroundings.

Anhidrosis or hypohidrosis caused by skin disease

Local

hypohidrosis has been reported in many skin diseases, especially those that

scar (e.g. lupus erythe-matosus and morphoea). It may be a feature of Sjogren’s

syndrome, ichthyosis, psoriasis and miliaria profunda .

Interference with sweat delivery

Miliaria.

This is the result of plugging or rupture ofsweat ducts. It occurs in hot humid

climates, at any age, and is common in over-clothed infants in hot nurseries.

The physical signs depend on where the ducts are blocked.

Miliaria

crystallina. This presents as tiny clear non-inflamed vesicles that

look like dew. This is the most superficial type.

Miliaria

rubra (prickly heat). Tiny erythematous andvery itchy papules.

Miliaria

profunda. These consist of larger erythema-tous papules or pustules.

This is the deepest type.

Treatment.

The best treatment is to move to a coolerclimate or into air conditioning.

Clothing that pre-vents the evaporation of sweat (e.g. nylon shirts) should be

avoided; cotton is best. Claims have been made for ascorbic acid by mouth, but

in our hands it rarely if ever helps. Topical steroids reduce irritation but

should only be used briefly. Calamine lotion cools and soothes.

Related Topics