Chapter: Introduction to the Design and Analysis of Algorithms : Dynamic Programming

Dynamic Programming

Chapter 8

Dynamic

Programming

An idea, like a ghost . . . must be spoken to a little before it

will explain itself.

ŌĆöCharles

Dickens (1812ŌĆō1870)

Dynamic programming is an

algorithm design technique with a rather interesting history. It was invented

by a prominent U.S. mathematician, Richard Bellman, in the 1950s as a general

method for optimizing multistage decision processes. Thus, the word

ŌĆ£programmingŌĆØ in the name of this technique stands for ŌĆ£planningŌĆØ and does not

refer to computer programming. After proving its worth as an important tool of

applied mathematics, dynamic programming has even-tually come to be considered,

at least in computer science circles, as a general algorithm design technique

that does not have to be limited to special types of optimization problems. It

is from this point of view that we will consider this tech-nique here.

Dynamic programming is a

technique for solving problems with overlapping subproblems. Typically, these

subproblems arise from a recurrence relating a given problemŌĆÖs solution to

solutions of its smaller subproblems. Rather than solving overlapping

subproblems again and again, dynamic programming suggests solving each of the

smaller subproblems only once and recording the results in a table from which a

solution to the original problem can then be obtained.

This technique can be

illustrated by revisiting the Fibonacci numbers dis-cussed in Section 2.5. (If

you have not read that section, you will be able to follow the discussion

anyway. But it is a beautiful topic, so if you feel a temptation to read it, do

succumb to it.) The Fibonacci numbers are the elements of the sequence

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, . . .

,

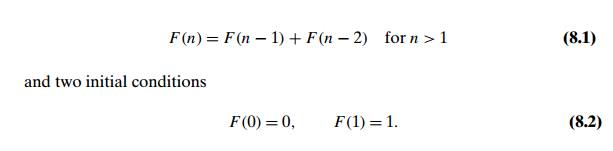

which can be defined by the

simple recurrence

If we try to use recurrence

(8.1) directly to compute the nth Fibonacci number F (n), we would have to recompute the same values of

this function many times (see Figure 2.6 for an

example). Note that the problem of computing F (n) is expressed in terms of its smaller and

overlapping subproblems of computing F (n ŌłÆ 1) and F (n ŌłÆ 2).

So we can simply fill elements of a one-dimensional array with the n + 1 consecutive values of F (n) by starting, in view of initial conditions

(8.2), with 0 and 1 and using equation (8.1) as the rule for producing all the

other elements. Obviously, the last element of this array will contain F (n). Single-loop pseudocode of this very simple

algorithm can be found in Section 2.5.

Note that we can, in fact,

avoid using an extra array to accomplish this task by recording the values of

just the last two elements of the Fibonacci sequence (Problem 8 in Exercises

2.5). This phenomenon is not unusual, and we shall en-counter it in a few more

examples in this chapter. Thus, although a straightforward application of

dynamic programming can be interpreted as a special variety of space-for-time

trade-off, a dynamic programming algorithm can sometimes be re-fined to avoid

using extra space.

Certain algorithms compute

the nth Fibonacci number without

computing all the preceding elements of this sequence (see Section 2.5). It is

typical of an algorithm based on the classic bottom-up dynamic programming

approach, however, to solve all

smaller subproblems of a given problem. One variation of the dynamic

programming approach seeks to avoid solving unnecessary subproblems. This

technique, illustrated in Section 8.2, exploits so-called memory functions and

can be considered a top-down variation of dynamic programming.

Whether one uses the

classical bottom-up version of dynamic programming or its top-down variation,

the crucial step in designing such an algorithm remains the same: deriving a

recurrence relating a solution to the problem to solutions to its smaller

subproblems. The immediate availability of equation (8.1) for computing the nth Fibonacci number is one of the few

exceptions to this rule.

Since a majority of dynamic

programming applications deal with optimiza-tion problems, we also need to

mention a general principle that underlines such applications. Richard Bellman

called it the principle of optimality. In terms some-what different from its

original formulation, it says that an optimal solution to any instance of an

optimization problem is composed of optimal solutions to its subin-stances. The

principle of optimality holds much more often than not. (To give a rather rare

example, it fails for finding the longest simple path in a graph.) Al-though

its applicability to a particular problem needs to be checked, of course, such

a check is usually not a principal difficulty in developing a dynamic

program-ming algorithm.

In the sections and exercises

of this chapter are a few standard examples of dynamic programming algorithms.

(The algorithms in Section 8.4 were, in fact, invented independently of the

discovery of dynamic programming and only later came to be viewed as examples

of this techniqueŌĆÖs applications.) Numerous other applications range from the

optimal way of breaking text into lines (e.g., [Baa00]) to image resizing

[Avi07] to a variety of applications to sophisticated engineering problems

(e.g., [Ber01]).

Related Topics