Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative Disorders

Dissociative phenomena are best understood through the term désagrégation (disaggregation)

originally given by Janet (1920). Events

normally experienced as connected to one another on a smooth continuum are

isolated from the other mental processes with which they would ordinarily be

associated. The dissocia-tive disorders are a disturbance in the organization

of identity, memory, perception, or consciousness. When memories are sep-arated

from access to consciousness, the disorder is dissociative amnesia.

Fragmentation of identity results in dissociative fugue or dissociative

identity disorder (DID; formerly multiple per-sonality disorder). Disintegrated

perception is characteristic of depersonalization disorder. Dissociation of

aspects of conscious-ness produces acute stress disorder and various

dissociative trance and possession states. Numbing and amnesia are diagnos-tic

components of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These dissociative and

related disorders are more a disturbance in the organization or structure of

mental contents than in the contents themselves. Memories in dissociative

amnesia are not so much distorted or bizarre as they are segregated from one

another. The identities lost in dissociative fugue or fragmented in DID are two-dimensional

aspects of an overall personality structure. In this sense, patients with DID

suffer not from having more than one personality but rather from having less

than one personality. The problem involves information processing: the failure

of inte-gration of elements rather than the contents of the fragments.

The dissociative disorders have a long history in classical

psychopathology, being the foundation on which Freud began his explorations of

the unconscious and Janet developed dissociation theory. Although much

attention in psychiatry has shifted to di-agnosis and treatment of mood,

anxiety and thought disorders, dissociative phenomena are sufficiently

persistent and interesting that they have elicited growing attention from both

professionals and the public. There are at least four reasons for this:

They are fascinating phenomena in and of

themselves, involv-ing the loss of or change in identity, or memory, or a

feeling of detachment from extreme and traumatic physical events.

·

Dissociative disorders seem to arise in response to

traumatic stress.

·

Dissociative disorders remain an area of

psychopathology for which the best treatment is psychotherapy, although

adjunc-tive pharmacological interventions can be helpful.

·

Dissociation as a phenomenon has much to teach us

about information processing in the brain.

Development of the Concept

The

dissociative disorders might have been studied more inten-sively during the

20th century had not Janet’s and Charcot’s workbeen so

thoroughly eclipsed by Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, emphasizing as it did

repression rather than dissociation.

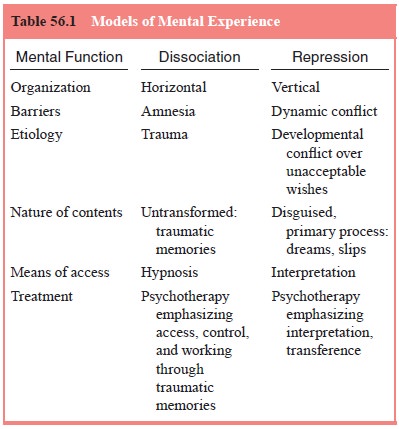

Hilgard (1977) developed a neodissociation theory that re-vived interest

in Janetian psychology and dissociative psychopa-thology. He postulated

divisions in mental structure that were hori-zontal rather than vertical, as

was the case in Freud’s archeological model. This model allowed for immediate

access to consciousness of any of a variety of warded-off memories, which is

not the case in Freud’s system. In the dynamic unconscious model, repressed

memories must first go through a process of transformation as they are accessed

and lifted from the depths of the unconscious, for ex-ample, through the

interpretation of dreams or slips of the tongue. In Hilgard’s model, amnesia is

a crucial mediating mechanism that cre-ates barriers dividing one set of mental

contents from another. Thus, flexible use of amnesia is conceptualized as a key

defensive strategy. Therefore, reversal of amnesia is an important therapeutic

tool.

Repression as a general model for keeping information out of conscious

awareness differs from dissociation in four impor-tant ways:

· In repression, information is disguised as well as hidden. Dis-sociated

information is stored in a discrete and untransformed manner, for example, as a

memory of some element of a trau-matic experience, whereas repressed

information is usually disguised and fragmented. Even when repressed

information becomes available to consciousness, its meaning is hidden, for

example, in dreams or slips of the tongue.

· Retrieval of repressed information requires translation. Re-trieval of

dissociated information can often be direct. Tech-niques such as hypnosis can

be used to access warded-off memories. By contrast, uncovering of repressed

information often requires repeated recall trials through intense question-ing,

psychotherapy, or psychoanalysis with subsequent inter-pretation (i.e., of

dreams).

· Repressed information is not discretely organized temporally. The

information kept out of awareness in dissociation is often for a discrete and

sharply delimited time, whereas repressed information may be for a type of

encounter or experience scat-tered across times.

· Repression is less specifically tied to trauma. Dissociation seems to be

elicited as a defense most commonly after epi-sodes of physical trauma, whereas

repression is in response to warded-off fears, wishes and other dynamic

conflicts.

Whether dissociation is a subtype of repression or vice versa, both are

important methods for managing complex and affec-tively charged information.

Given the complexity of human in-formation processing, the synthesis of

perception, cognition and

affect is a major task. Mental function is composed of a variety of

reasonably autonomous subsystems involving a perception, memory storage and

retrieval, intention and action. Indeed, the accomplishment of a sense of

mental unity is an achievement, not a given. It is remarkable not that

dissociative disorders occur at all, but rather that they do not occur more

often. Models of mental experience are presented in Table 56.1.

Related Topics