Chapter: Nutrition and Diet Therapy: Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism

Digestion

DIGESTION

Digestion is the process whereby

food is broken down into smaller parts,chemically changed, and moved through

the gastrointestinal system. The gas-trointestinal (GI)

tract consists of the body structures that participate indigestion.

Digestion begins in the mouth and ends at the anus. Along the entire GI tract

secretions of mucus lubricate and protect the mucosal tissues. As the process

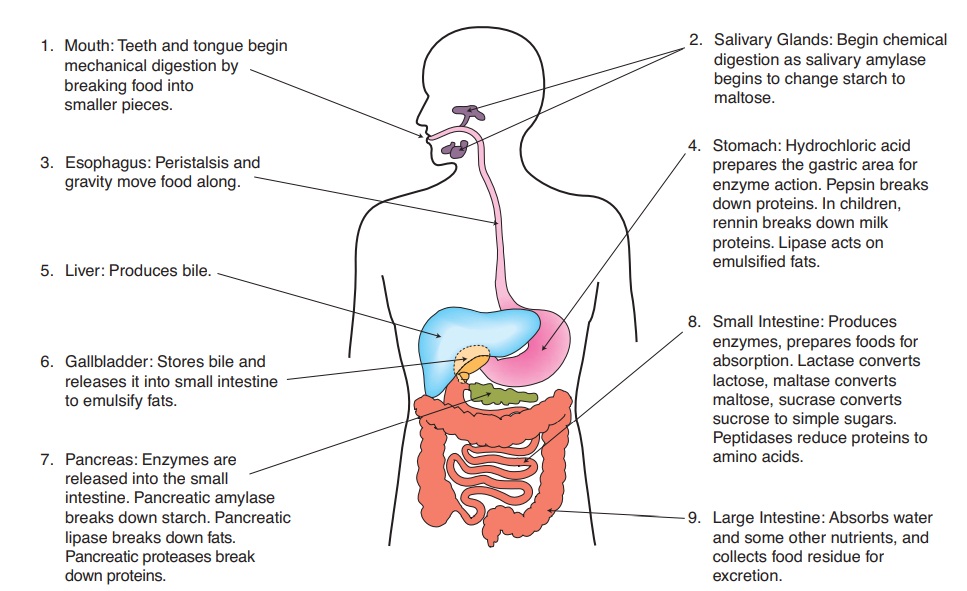

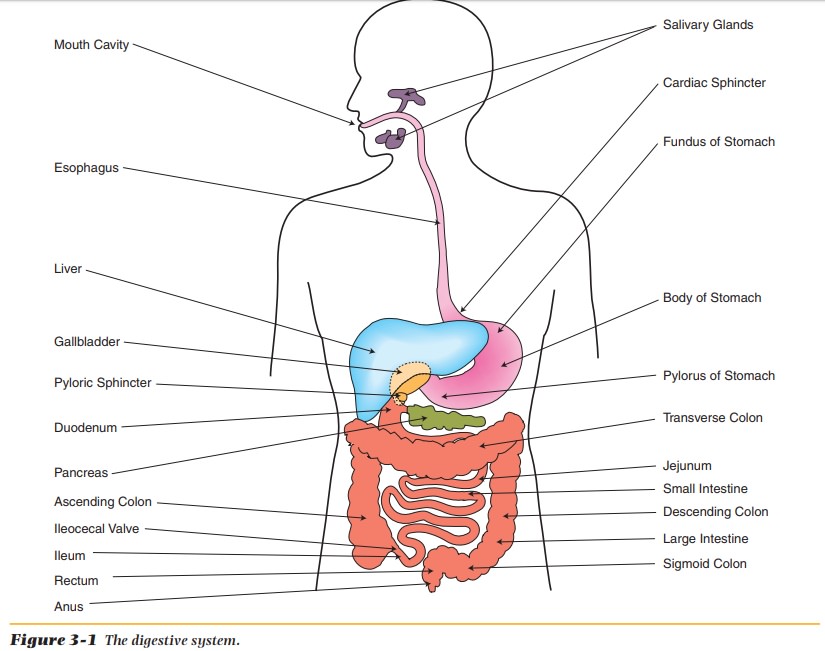

of digestion is discussed, refer to Figure 3-1 and note the locations of the

structures that perform the functions of digestion.

Digestion occurs

through two types of action—mechanical and chemi-cal. During mechanical digestion, food is broken into

smaller pieces by the teeth. It is then moved along the gastrointestinal tract

through the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. This movement is caused by a

rhythmic contraction of the muscular walls of the tract called peristalsis. Mechanical digestion

helps to prepare food for chemical digestion by breaking it into smaller

pieces. Several small pieces collectively have more surface area than fewer

large ones and thus are more readily broken down by digestive juices.

During chemical digestion, the composition of

carbohydrates, pro-teins, and fats is changed. Chemical changes occur through

the addition of water and the resulting splitting, or breaking down, of the

food molecules. This process is called hydrolysis. Food is broken down

into nutrients that the tissues can absorb and use. Hydrolysis also involves

digestive enzymes that act on food

substances, causing them to break down into simple compounds. An enzyme can

also act as a catalyst, which speeds up the

chemical reactions without itself being changed in the process. Digestive

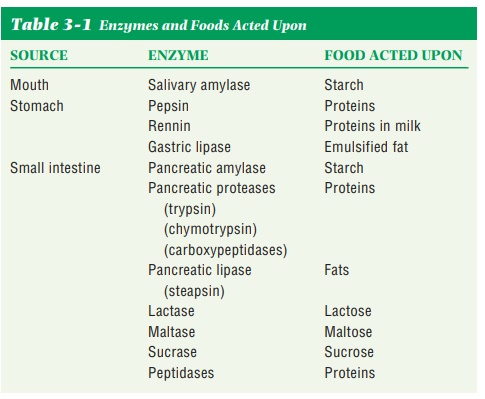

enzymes are secreted by the mouth, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine

(Table 3-1). An enzyme is often named for the substance on which it acts. For

example, the enzyme sucrase acts on sucrose, the enzyme maltase acts on

maltose, and lactase acts on lactose.

Digestion in the Mouth

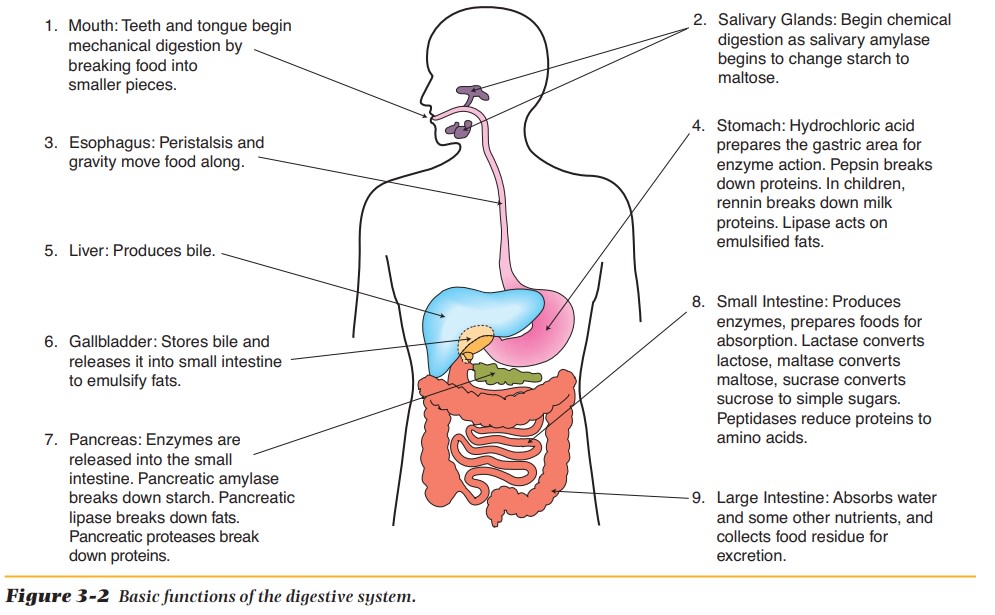

Digestion begins in the mouth, where the food is broken into smaller pieces by the teeth and mixed with saliva (Figure 3-2). At this point, each mouthful of food that is ready to be swallowed is called a bolus. Saliva is a secretion of the salivary glands that contains water, salts, and a digestive enzyme called salivary amylase (also called ptyalin), which acts on complex carbo-hydrates (starch). Food is normally held in the mouth for such a short time that only small amounts of carbohydrates are chemically changed there. The salivary glands also secrete a mucous material that lubricates and binds food particles to help in swallowing the bolus. The final chemical digestion of carbohydrates occurs in the small intestine.

The Esophagus

The esophagus is a 10-inch muscular

tube through which food travels from the mouth to the stomach. When swallowed,

the bolus of food is moved down the esophagus by peristalsis and gravity. At

the lower end of the esophagus, the cardiac sphincter opens to allow

passage of the bolus into the stomach. The cardiac sphincter prevents the

acidic content of the stomach from flowing back into the esophagus. When this

sphincter mal-functions, it causes acid reflux disease.

Digestion in the Stomach

The stomach consists

of an upper portion known as the fundus, a middle area known

as the body of the stomach, and the end nearest the small intestine called the pylorus. Food enters the

fundus and moves to the body of the stom-ach, where the muscles in the stomach

wall gradually knead the food, tear it, and mix it with gastric juices, and

with the intrinsic factor necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12,

before it can be propelled forward in slow, controlled movements. The food

becomes a semiliquid mass called chyme (pronounced “kime”).

When the chyme enters the pylorus, it causes distention and the re-lease of the

hormone gastrin, which increases the

release of gastric juices.Gastric juices are digestive

secretions of the stomach. They containhydrochloric acid, pepsin, and mucus.

Hydrochloric acid activates the enzyme pepsin, prepares protein molecules for

partial digestion by pepsin, destroys most bacteria in the food ingested, and

makes iron and calcium more soluble. As the hydrochloric acid is released, a

thick mucus is also secreted to protect the stomach from this harsh acid. In

children, there are two additional enzymes: rennin, which acts on milk protein

and casein, and gastric lipase, which breaks the butterfat molecules of milk

into smaller molecules.

In summary, the

functions of the stomach include the following:

• Temporary storage of food

• Mixing of food with gastric juices

• Regulation of a slow, controlled emptying of food into the

intestine

• Secretion of the intrinsic factor for vitamin B12

• Destruction of most bacteria inadvertently consumed

Digestion in the Small Intestine

Chyme moves through

the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum, the first sec-tion of

the small intestine. Chyme subsequently passes through the jejunum, the midsection of the

small intestine, and the ileum, the last section of

the small intestine.

When food reaches the

small intestine, the hormone secretin causes the pancreas

to release sodium bicarbonate to neutralize the acidity of the chyme. The

gallbladder is triggered by the hormone cholecystokinin

(CCK), which is pro-duced by intestinal mucosal glands when fat

enters, to release bile. Bile is produced in

the liver but stored in the gallbladder. Bile emulsifies fat after it is

secreted into the small intestine. This action enables the enzymes to digest

the fats more easily.

Chyme also triggers

the pancreas to secrete its juice into the small intes-tine. Pancreatic juice

contains the following enzymes:

• Trypsin, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidases split proteins

intosmaller substances. These are called pancreatic

proteases because they are protein-splitting enzymes produced by the

pancreas.

• Pancreatic amylaseconverts starches (polysaccharides)

to simplesugars.

• Pancreatic lipasereduces fats to fatty

acids and glycerol.

The small intestine

itself produces an intestinal juice that contains the enzymes lactase, maltase, and sucrase. These enzymes split

lactose, maltose, and sucrose, respectively, into simple sugars. The small

intestine also produces enzymes called peptidases that break down

proteins into amino acids.

The Large Intestine

The large intestine,

or colon, consists of the

cecum, colon, and rectum. The cecum is a blind pouchlike beginning of the colon

in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. The appendix is a diverticulum that

extends off the cecum. Thececum is separated from the ileum by the ileocecal

valve and is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine (colon). Its

primary function is to absorb water and salts from undigested food. It has a

muscular wall that can knead the contents to enhance absorption. One of the end

products of fermentation in the cecum is volatile fatty acids. The major

volatile fatty acids are acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These are absorbed

from the large intestine and used as sources of energy. The digested food then

enters the ascending colon and moves through the transverse colon and on to the

descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and, finally, the anal canal.

Related Topics