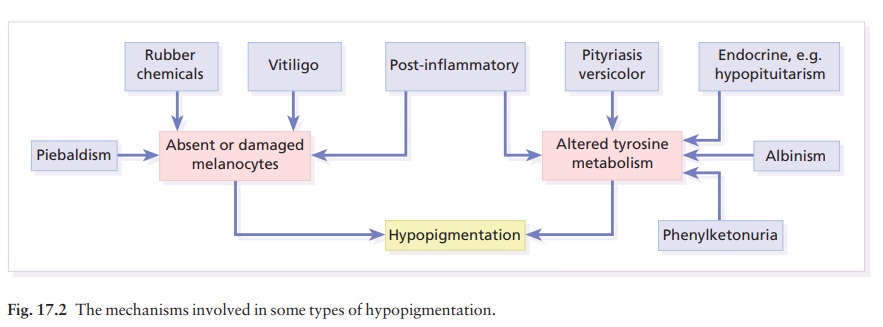

Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Disorders of pigmentation

Decreased melanin pigmentation

Decreased

melanin pigmentation

Some

conditions in which there is a lack of melanin are listed in Table 17.2.

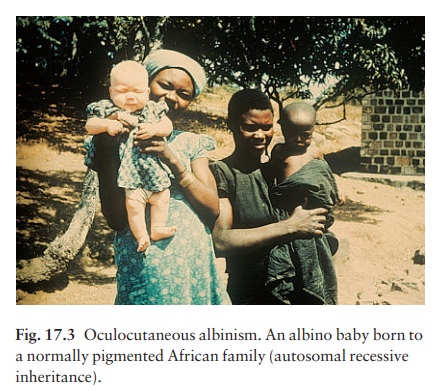

Oculocutaneous albinism

In

this condition, little or no melanin is made either in the skin and eyes

(oculocutaneous albinism) or in the eyes alone (ocular albinismanot discussed

further here). The prevalence of albinism of all types ranges from 1 in 20 000

in the USA and UK to 5% in some communities.

Cause

The hair bulb test (see Investigations) separates oculocutaneous albinism into two main types: tyrosinase-negative and tyrosinase-positive.

Roughly equal

numbers of the two types are found in most communities, both being inherited as

autosomal recessive traits. This explains how children with two albino parents

can sometimes themselves be normally pigmented, the genes being complementary

in the double heterozygote (Fig. 17.3).

The

tyrosinase gene lies on chromosome 11q14-q21. More than 20 allelic variations have

been found there in patients with tyrosinase-negative albinism. The gene for

tyrosinase-positive human albinism has been mapped to chromosome 15q11-q13. It

probably encodes for an ion channel protein in the melanosome involved in the

transport of tyrosine.

Presentation and course

The

whole skin is white and pigment is also lacking in the hair, iris and retina

(Fig. 17.3). Albinos have poor sight, photophobia and a rotatory nystagmus. As

they grow older tyrosinase-positive albinos gain a little pigment in their

skin, iris and hair. Negroid skin becomes yellow-brown and the hair becomes

yellow. Albinos may also develop freckles. Sunburn is common on unprotected

skin. As melanocytes are present, albinos have non-pigmented melano-cytic naevi

and may develop amelanotic malignant melanomas.

Complications

In the tropics these unfortunate individuals develop numerous sun-induced skin tumours even when they are young, confirming the protective role of melanin.

Differential diagnosis

Piebaldism

and vitiligo are described below.

Investigations

Prenatal

diagnosis of albinism is now possible but may not be justifiable in view of the

good prognosis. A biopsy from fetal skin, taken at 20 weeks, is examined by

electron microscopy for arrested melanosome development.

The

hair bulb test, in which plucked hairs are incubated in dihydroxyphenylalanine,

distinguishes tyrosinase-positive from tyrosinase-negative types. Those whose

hair bulbs turn black (tyrosine-positive) are less severely affected.

Treatment

Avoidance

of sun exposure, and protection with opaque clothing, wide-brimmed hats and

sunscreen creams (Formulary 1), are essential and allow albinos in temperate

climates to live a relatively normal life. Early diagnosis and treatment of

skin tumours is critical. In the tropics the outlook is less good and the

termination of affected pregnancies may be considered.

Piebaldism

These

patients often have a white forelock of hair and patches of depigmentation

lying symmetrically on the limbs, trunk and central part of the face,

especially the chin. The condition is present at birth and is inherited as an

autosomal dominant trait. A genetic abnormal-ity in mice (dominant white

spotting) provided the clue that allowed the human piebaldism gene to be mapped

to chromosome 4q12, where the KIT pro-tooncogene lies. This encodes

the tyrosine kinase transmembrane cellular receptor on certain stem cells;

without this they cannot respond to normal signals for development and migration.

Melanocytes are absent from the hypopigmented areas. The depigmen-tation, often

mistaken for vitiligo, may improve with age. There is no effective treatment.

Waardenburg’s syndrome includes piebaldism (with a white forelock in 20% of

cases), hypertelorism, a prominent inner third of the eyebrows, irides of

different colour and deafness.

Phenylketonuria

This

rare metabolic cause of hypopigmentation has a prevalence of about 1 : 25 000.

Hypopituitarism

The

skin changes here may alert an astute physician to the diagnosis. The

complexion has a pale, yellow tinge; there is thinning or loss of the sexual

hair; the skin itself is atrophic. The hypopigmentation is caused by a

decreased production of pituitary melan-otrophic hormones .

Vitiligo

The

word vitiligo comes from the Latin word vitellus, which

means ‘veal’ (pale, pink flesh). It is an acquired circumscribed

depigmentation, found in all races; its prevalence may be as high as 0.5–1%;

its inheritance is polygenic.

Cause and types

There

is a complete loss of melanocytes from affected areas. There are two main

patterns: a common gener-alized one and a rare segmental type. Generalizedvitiligo,

including the acrofacial variant, usually startsafter the second decade. There

is a family history in 30% of patients and this type is most frequent in those

with autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, thyroid disorders and pernicious

anaemia. It is postulated that in this type melanocytes are the target of a

cell-mediated autoimmune attack. Segmental vitiligo is restricted

to one part of the body, but not necessarily to a dermatome. It occurs earlier

than generalized vitiligo, and is not associated with autoimmune dis-eases.

Trauma and sunburn can precipitate both types.

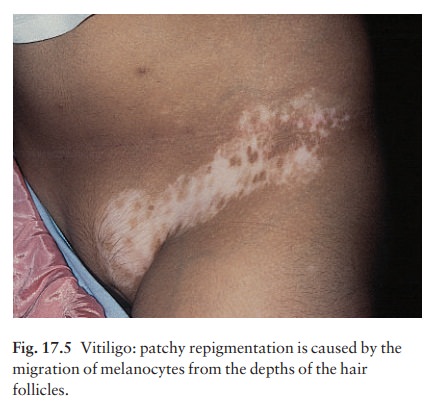

Clinical course

Generalized

type. The sharply defined, usually sym-metrical (Fig. 17.4),

white patches are especially common on the backs of the hands, wrists, fronts

of knees, neck and around body orifices. The hair of the scalp and beard may

depigment too. In Caucasoids, the surrounding skin is sometimes hyperpigmented.

The

course is unpredictable: lesions may remain static or spread; occasionally they

repigment spontan-eously from the hair follicles.

Segmental

type. The individual areas look like thegeneralized type but

their segmental distribution is striking. Spontaneous repigmentation occurs

more often in this type than in generalized vitiligo (Fig. 17.5).

Differential diagnosis

Contact

with depigmenting chemicals, such as hydroquinones and substituted phenols in

the rubber industry, should be excluded. Pityriasis versicolor must be considered; its fine scaling and less

The patches of piebaldism are present at birth.

Sometimes leprosy must be excludedaby sens-ory testing and a general

examination. Other tropical diseases that cause patchy hypopigmentation are

leishmaniasis, yaws and pinta.

Treatment

Treatment

is unsatisfactory. Recent patches may respond to a potent or very potent

topical steroid, applied for 1–2 months. After this, the strength should be

gradually tapered to a mildly potent steroid for maintenance treatment. Some patients

improve with psoralens (trimethylpsoralen or 8-methoxypsoralen, in a dosage of

0.4–0.6 mg/kg body weight), taken 1–2 h before graduated exposure to natural

sunshine or to artificial UVA (PUVA;). Narrow band (311 nm) UVB may also be

effective. Therapy is given 2–3 times weekly for at least 6 months; new lesions

seem to respond best. Autologous skin grafts are becoming popular in some

centres although they remain experimental. The two most common pro-cedures are

minigrafting (implants of 1 mm grafts from unaffected skin) and suction blister

grafting (using the epidermal roofs of suction blisters from unaffected skin

for grafting). Melanocyte and stem cell transplants, in which single cell

suspensions are made from unaffected skin and applied to dermab-raded

vitiliginous skin, are also being investigated. The use of these techniques may

be limited by cost, and by the development of vitiligo (Köbner pheno-menon) at

donor sites.

As a general rule, established vitiligo is best left untreated in most white people, although advice about suitable camouflage preparations (Formulary 1) to cover unsightly patches should be given. Sun avoidance and screening preparations (Formulary 1) are needed to avoid sunburn of the affected areas and a heightened contrast between the pale and dark areas. Black patients with extensive vitiligo can be completely and irreversibly depigmented by creams containing the monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone.

The

social implications of this must be discussed and carefully considered, and

written consent given before such treatment is undertaken.

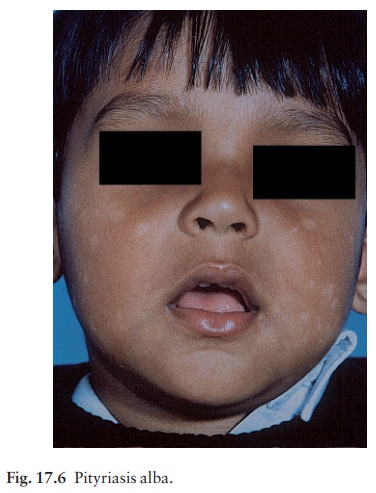

Postinflammatory depigmentation

This

may follow eczema, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, lupus erythematosus and, rarely,

lichen planus. It may also result from cryotherapy or a burn. In general, the

more severe the inflammation, the more likely pigment is to decrease rather

than increase in its wake. These prob-lems are most significant in Negroids or

Asians. With time, the skin usually repigments. Pityriasis alba is common on

the faces of children. The initial lesion is probably a variant of eczema

(pinkish with fine scal-ing), which fades leaving one or more pale, slightly

scaly, areas (Fig. 17.6). Exposure to the sun makes the patches more obvious.

White hair

Melanocytes

in hair bulbs become less active with age and white hair (canities) is a

universal sign of ageing. Early greying of the hair is seen in the rare

premature ageing syndromes, such as Werner’s syndrome, and in autoimmune

conditions such as pernicious anaemia, thyroid disorders and Addison’s disease.

Related Topics