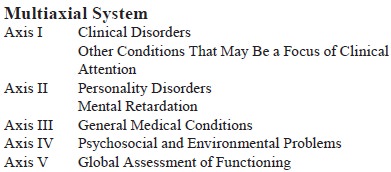

Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychiatric Classification

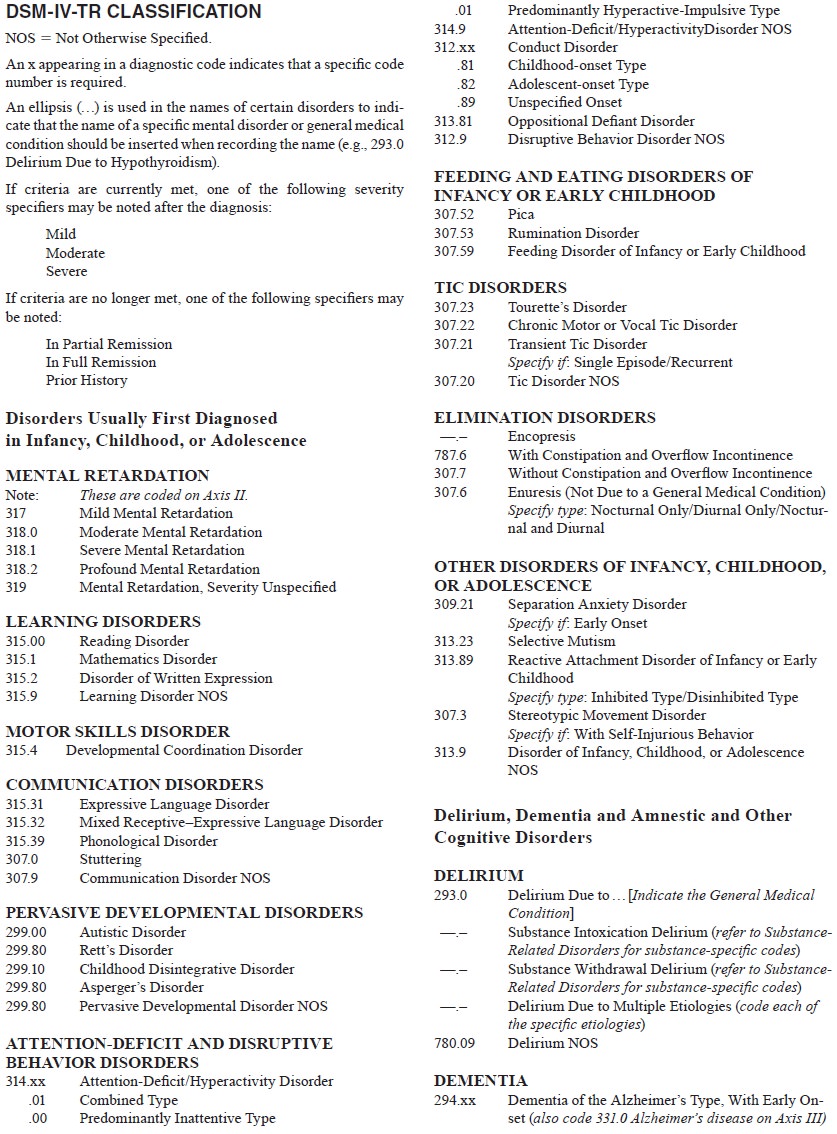

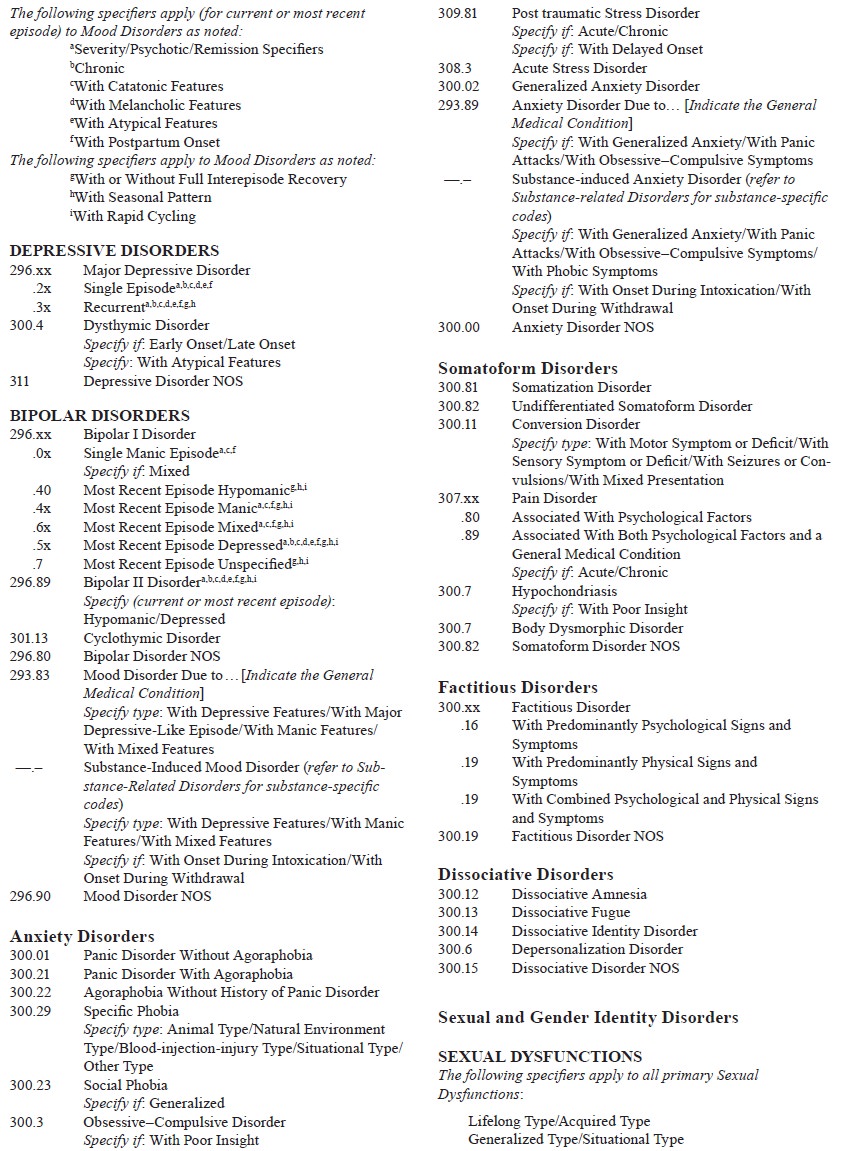

DSM-IV-TR Classification and Diagnostic Codes

DSM-IV-TR Classification and

Diagnostic Codes

The “DSM-IV-TR Classification of Mental Disorders’’

refers to the comprehensive listing of the official diagnostic codes,

catego-ries, subtypes and specifiers (see below). It is divided into vari-ous

“diagnostic classes’’ which group disorders together based on common presenting

symptoms (e.g., mood disorders, anxiety disorders), typical age-at-onset (e.g.,

disorders usually first diag-nosed in infancy, childhood and adolescence), and

etiology (e.g., substance-related disorders, mental disorders due to a general

medical condition).

The diagnostic codes listed in the DSM-IV are derived from the International Classifi cation of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), the official coding system for reporting morbidity and mortality in the USA. That is the reason why the codes go from 290.00 to 319.00; they are actually de-rived from the mental disorders section of a much larger coding system for all medical disorders that extends from 001 to 999. Clinicians working in the USA are required to use ICD-9-CM in order to receive reimbursement from both government agencies (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid) and private insurers.

Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence

The classification begins with disorders usually

first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence. The provision for a

separate section for so-called childhood disorders is only for convenience.

Although most individuals with these disorders present for clinical attention

during childhood or adolescence, it is not uncommon for some of these

conditions to be diagnosed for the first time in adulthood (e.g.,

attention-deficit/hyperac-tivity disorder). Moreover, many disorders included

in other sections of the DSM-IV have an onset during childhood (e.g., major

depressive disorder). Thus, a clinician evaluating a child or adolescent should

not only focus on those disorders listed in this section but also consider

disorders from throughout the DSM-IV. Similarly, when evaluating an adult, the

clinician should also consider the disorders in this section since many of them

persist into adulthood (e.g., stuttering, learning disorders, tic disorders).

The first set of disorders included in this

diagnostic class (mental retardation, learning and motor skills disorders, and

communication disorders). While they are not, strictly speak-ing, regarded as

mental disorders, they are included in the DSM-IV-TR to facilitate differential

diagnosis and to increase recognition of these conditions among mental health

profes-sionals. Autism and other pervasive developmental disorders are

characterized by gross qualitative impairment in social re-latedness, in

language, and in repertoire of interests and ac-tivities. Disorders covered include

autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, Rett’s disorder and childhood

disintegrative disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other

disruptive behavior disorders are grouped together because they are all

characterized (at least in their childhood presentations) by dis-ruptive

behavior.

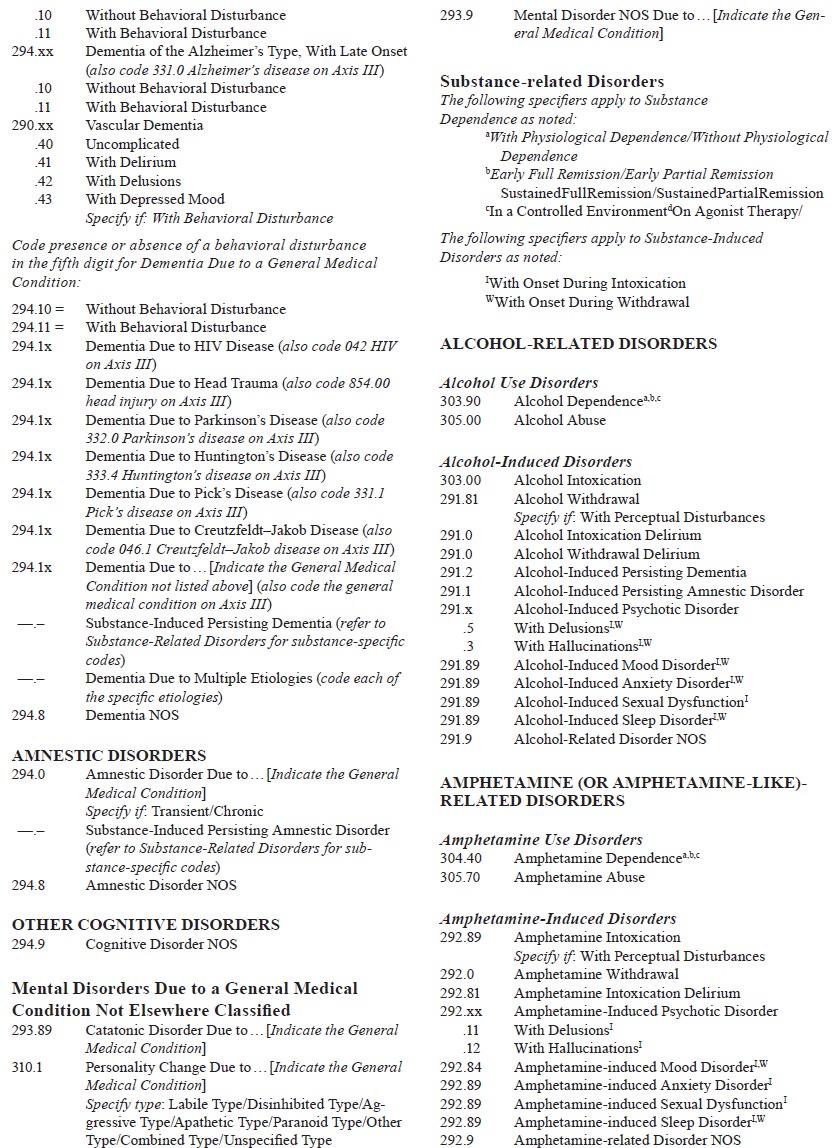

Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic Disorder and Other Cognitive Disorders

In the previous DSM-III-R, delirium, dementia,

amnestic dis-order and other cognitive disorders were included in a section

called “organic mental disorders’’, which contained disorders that were due to

either a general medical condition or substance use. In DSM-IV-TR, the term organic was eliminated because of the

implication that disorders not included in that section (e.g., schizophrenia,

bipolar disorder) did not have an organic compo-nent (Spitzer et al., 1992). In fact, virtually all

mental disorders have both psychological and biological components, and to

des-ignate some disorders as organic and the remaining disorders as nonorganic

reflected a reductionistic mind–body dualism that is at odds with our

understanding of the multifactorial nature of the etiological underpinnings of

disorders.

DSM-IV-TR replaced each unitary organic mental

disor-der (e.g., organic mood disorder) with its two component parts: mood

disorder due to a general medical condition and sub-stance-induced mood

disorder. Because of their central roles in the differential diagnosis of

cognitive impairment, delirium, dementia and amnestic disorder are contained within

the same diagnostic class in DSM-IV-TR.

Whereas both delirium and dementia are

characterized by multiple cognitive impairments, delirium is distinguished by

the presence of clouding of consciousness, which is manifested by an inability

appropriately to maintain or shift attention. DSM-IV-TR includes three types of

delirium: delirium due to a general medical condition, substance-induced

delirium and delirium due to multiple etiologies.

Dementia is characterized by clinically significant

cog-nitive impairment in memory that is accompanied by impair-ment in one or

more other areas of cognitive functioning (e.g., language, executive

functioning). DSM-IV-TR includes several types of dementia based on etiology,

including dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, vascular dementia, a variety of

dementia due to general medical and neurological conditions (e.g., human

immunodeficiency virus infection, Parkinson’s disease), sub-stance-induced

persisting dementia and dementia due to mul-tiple etiologies.

In contrast to dementia, amnestic disorder is

characterized by clinically significant memory impairment occurring in the

ab-sence of other significant impairments in cognitive functioning. DSM-IV-TR

includes amnestic disorder due to a general medical condition and substance-induced

persisting amnestic disease.

Mental Disorders Due to a General Medical Condition Not Elsewhere Classified

This diagnostic class includes all of the specific

mental disorders due to a general medical condition.. In DSM-IV-TR, most of the

mental disorders due to a general medical condition have been distributed

throughout the various diagnostic classes alongside their “nonorganic’’

counterparts in the classification. For exam-ple, mood disorder due to a

general medical condition and sub-stance-induced mood disorder are included in

the mood disorders section of DSM-IV-TR. Two specific types of mental

disorderdue to a general medical condition (i.e., catatonic disorder due to a

general medical condition and personality change due to a general medical

condition) are physically included in this diag-nostic class.

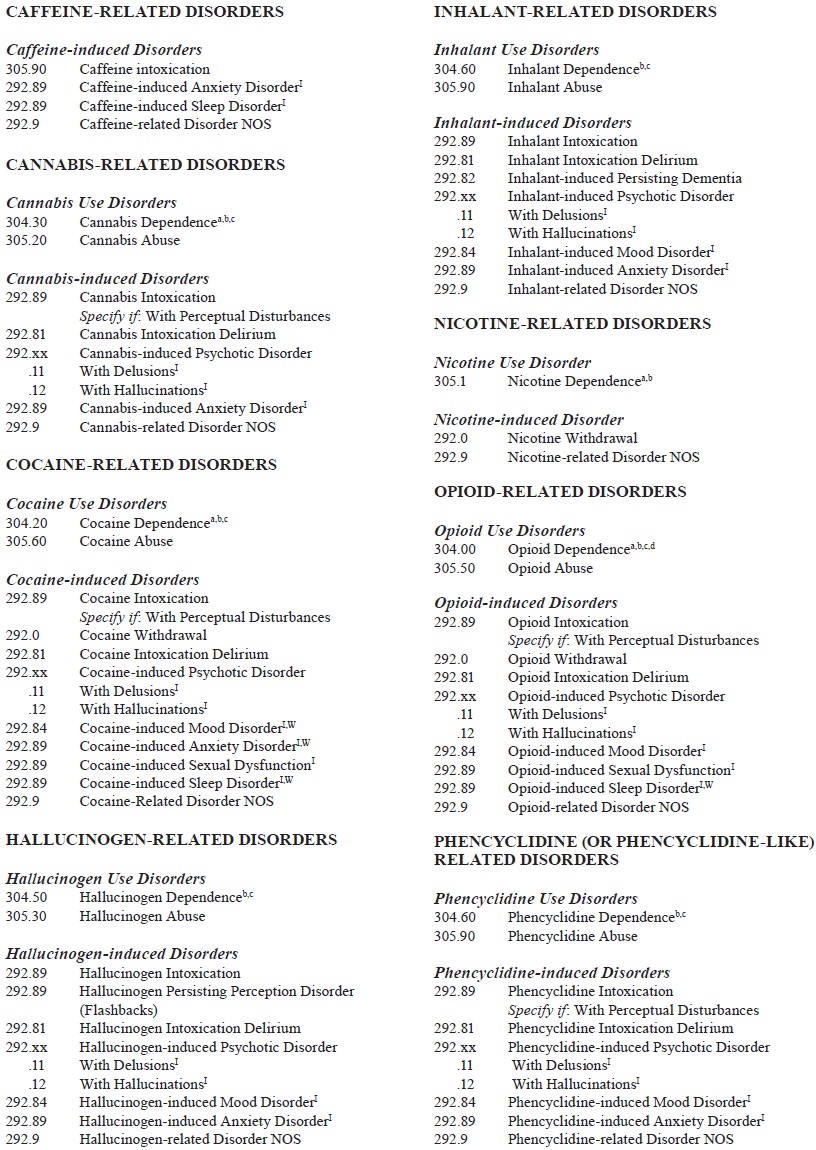

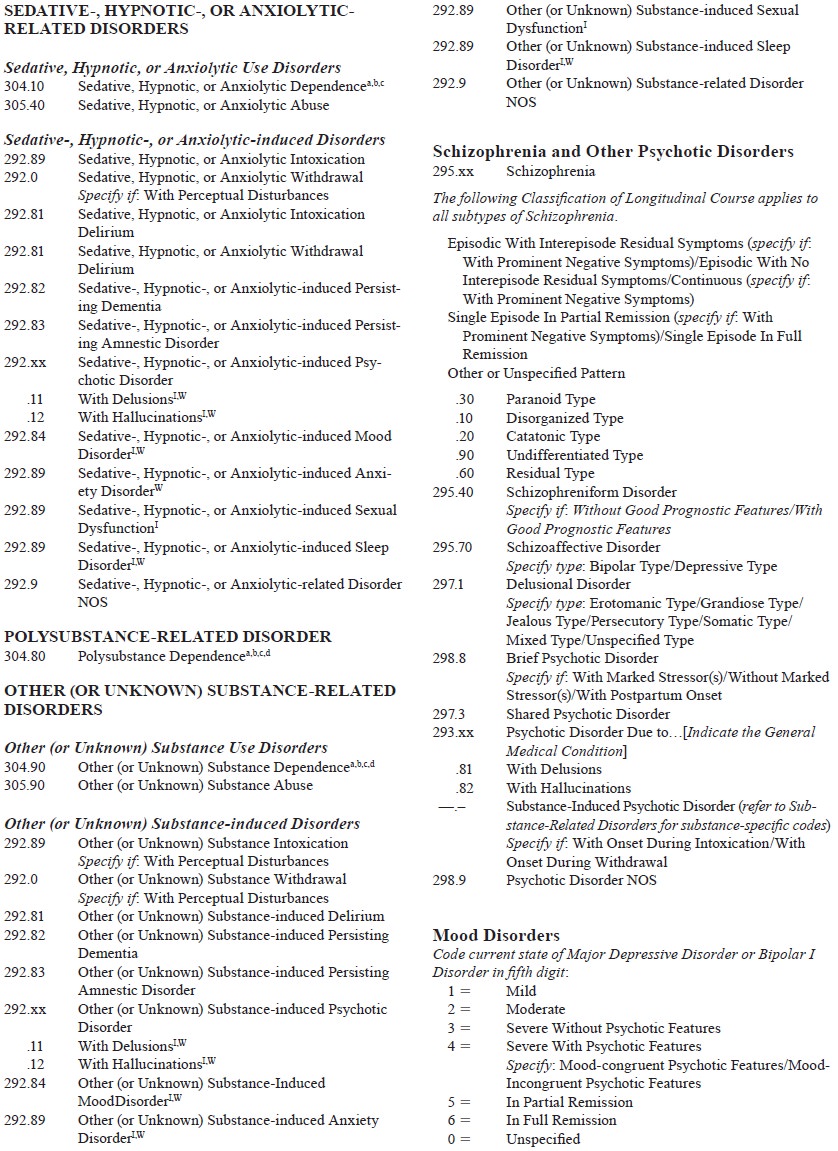

Substance-related Disorders

The term substance

in DSM-IV has a broader meaning than merely a drug of abuse. It also includes

medication side effects and the consequences of toxin exposure. Two types of

substance-related disorders are included in DSM-IV-TR: substance use dis-orders

(dependence and abuse), which describe the maladaptive nature of the pattern of

substance use; and substance-induced disorders, which cover psychopathological

processes caused by the direct effects of substances on the central nervous

system. Criteria sets for substance dependence, substance abuse, sub-stance

intoxication and substance withdrawal that apply across all drug classes are

included before the substance-specific sec-tions of DSM-IV.

Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

The title of this diagnostic class is potentially

misleading for two reasons: 1) there are other disorders that have psychotic

features that are not included in this diagnostic class (e.g., mood disorders

with psychotic features, delirium) and 2) it may incorrectly imply that the

other psychotic disorders included in this section are re-lated in some way to

schizophrenia (which is only true for schizo-phreniform disorder and possibly

schizoaffective disorder). In-stead, what ties together all of the disorders in

this diagnostic class is the presence of prominent psychotic symptoms. Included

here are schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffec-tive disorder,

delusional disorder, shared psychotic disorder and brief psychotic disorder..

It should be noted that the definition of the term psychosis has been used in different

ways historically and is not even used consistently across the various

categories in the DSM-IV-TR. The most restrictive definition of psychosis (used

in substance-induced psychotic disorder) requires a break in reality testing

such that the person has delusions or hallucinations with no in-sight into the

fact that the delusions or hallucinations are caused by taking drugs.

Mood Disorders

This diagnostic class includes disorders in which

the predomi-nant disturbance is in the individual’s mood. Although the term mood is broadly defined to include

depression, euphoria, anger and

anxiety, the DSM-IV-TR generally restricts mood distur-bances to depressed,

elevated, or irritable mood.

The mood disorders section begins with the criteria

for mood episodes (major depressive episode, manic episode, hy-pomanic episode,

mixed episode), which are the building blocks for the episodic mood disorders.

The codable mood disorders come next and are divided into the depressive

disorders (i.e., major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder, and the

bi-polar disorders (i.e., bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder and

cyclothymic disorder). Finally, the many specifiers that provide important

treatment-relevant information close this section. Several so-called

“subthreshold mood disorders’’ (i.e., they are characterized by depression but

fall short of meeting the diag-nostic criteria for either major depressive

disorder or dysthymicdisorder) are included in DSM-IV-TR appendix B, for Criteria

Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study. These include minor depressive

disorder, brief recurrent depressive disorder, mixed anxiety depressive

disorder, postpsychotic depressive disorder of schizophrenia and premenstrual

dysphoric disorder.

Anxiety Disorders

The common element joining these disparate

categories together is the fact that the anxiety is a prominent part of their

clinical presentation. This grouping has been criticized because of evi-dence

suggesting that at least some of the disorders are likely to be etiologically

distinct from the others. Most particularly, obses-sive–compulsive disorder and

post traumatic stress disorder seem to share little in common with the other

anxiety disorders. In fact, separate diagnostic classes for stress-related

disorders (that would also include adjustment disorders and perhaps

dissocia-tive disorders) and for obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders (which

might also include trichotillomania, tic disorders, hypo-chondriasis, body

dysmorphic disorder and other disorders char-acterized by compulsive behavior)

have been proposed.

Somatoform Disorders

This diagnostic class includes disorders in which

the defining feature is a physical complaint or bodily concern that is not

better accounted for by a general medical condition or another mental disorder.

These disorders can be divided into three groups based on the focus of the

individual’s concerns: 1) focus on the physical symptoms themselves

(somatization disorder, undifferentiated somatoform disorder, pain disorder and

conversion disorder); 2) focus on the belief that one has a serious physical

illness (hypo-chondriasis); and 3) focus on the belief that one has a defect in

physical appearance (body dysmorphic disorder).

Factitious Disorders

This diagnostic class contains only one disorder:

factitious disorder, which describes presentations in which the individual

intentionally produces or feigns physical or psychological symp-toms in order

to fulfill a psychological need to assume the sick role. Factitious disorder

should always be distinguished from malingering, in which the individual

similarly pretends to have physical or psychological symptoms. The difference

is that in malingering, the person’s motivation is to achieve some external

gain (e.g., disability benefits, lessening of criminal responsibility, shelter

for the night). For this reason, unlike factitious disorder, malingering is not

considered a mental disorder.

Dissociative Disorders

The common element to this group of disorders is

the symptom of dissociation, which is defined as a disruption in the usually

integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity and per-ception. Four

specific disorders are included: dissociative amne-sia, dissociative fugue,

dissociative identity disorder and deper-sonalization disorder.

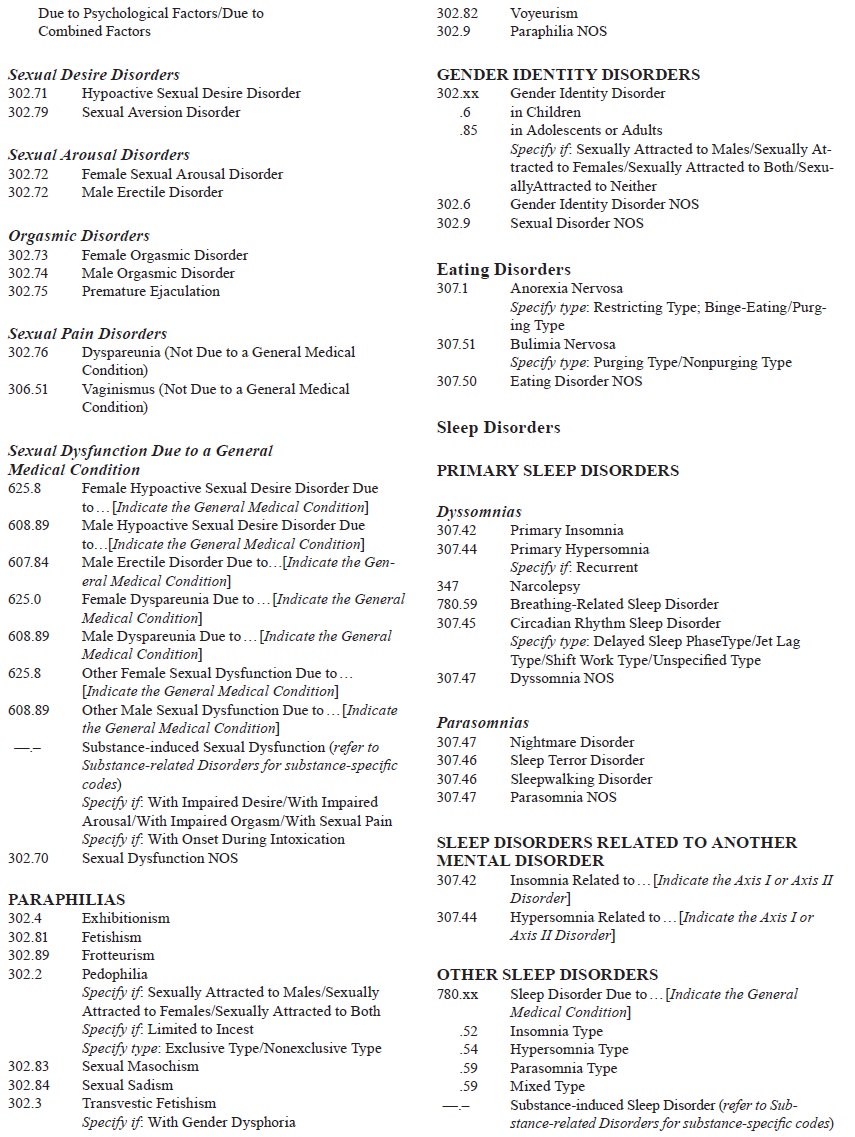

Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders

This diagnostic class contains three relatively

disparate types of disorders, linked together only by virtue of their

involvement in human sexuality. Sexual dysfunctions refer to disturbances in

sexual desire or functioning, paraphilias refer to unusual sexual preferences

that interfere with functioning (or in the case of preferences that involve

harm to others like pedophilia, merely acting on those preferences), and gender

identity disorder refers to a serious conflict between one’s internal identity

of maleness and femaleness (gender identity) and one’s anatomical sexual

characteristics.

Eating Disorders

Although the name of this diagnostic class focuses

on the fact that the disorders in this section are characterized by abnormal

eating behavior (refusal to maintain adequate body weight in the case of

anorexia nervosa and discrete episodes of uncontrolled eating of excessively

large amounts of food in the case of bulimia nervosa), of near equal importance

is the individual’s pathological overem-phasis on body image. A third category,

which is being actively researched but has not been officially added to the

DSM-IV-TR, is binge-eating disorder (included in the appendix of Criteria Sets

and Axes Provided for Further Study). Like bulimia nervosa, in-dividuals with

binge-eating disorder have frequent episodes of binge-eating. However, unlike

bulimia nervosa, these individu-als do not do anything significant to

counteract the effects of their binge-eating (i.e., they do not purge, use

laxatives or diet pills, or excessively exercise).

Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders are grouped into four sections on

the basis of presumed etiology (primary, related to another mental disor-der,

due to a general medical condition, and substance-induced). Two types of

primary sleep disorders are included in DSM-IV-TR: dyssomnias (problems in

regulation of amount and quality of sleep) and parasomnias (events that occur

during sleep). The dyssomnias include primary insomnia, primary hypersomnia,

circadian rhythm sleep disorder, narcolepsy and breathing-re-lated sleep

disorder, whereas the parasomnias include nightmare disorder, sleep terror

disorder and sleepwalking disorder.

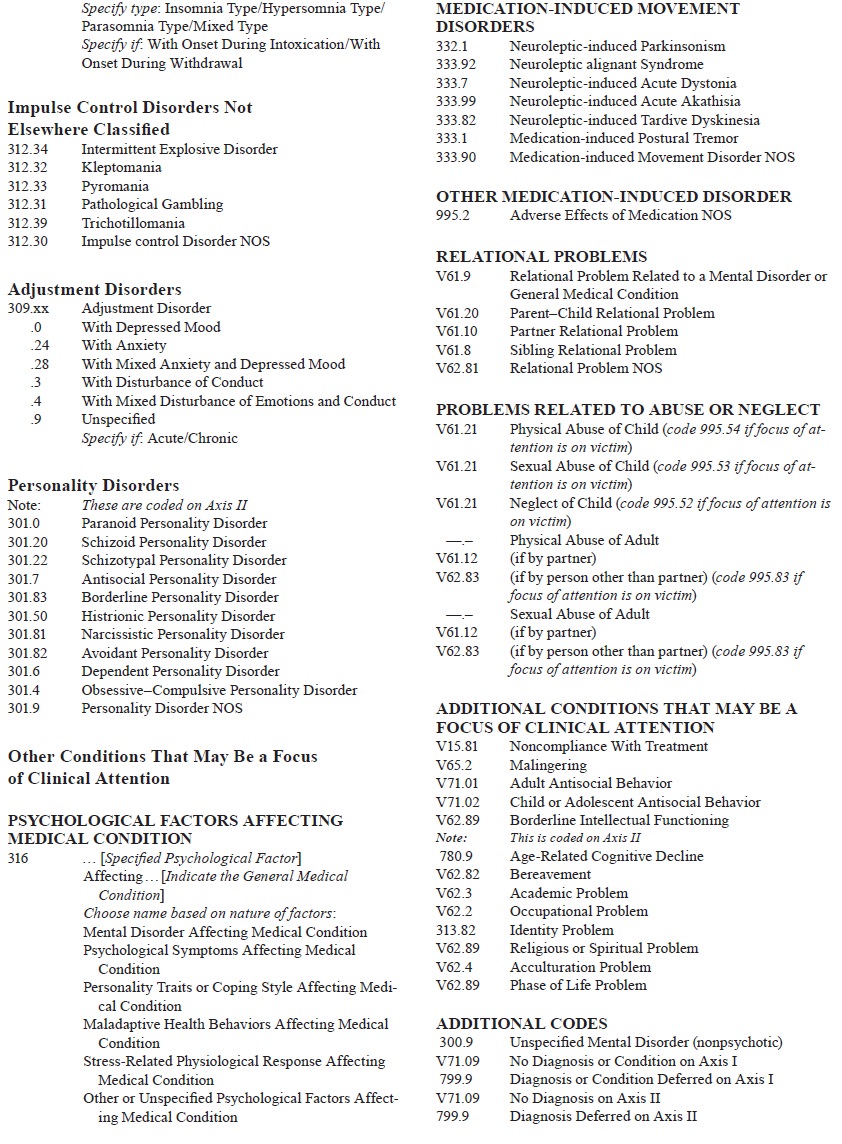

Impulse Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified

As is suggested by the title of this diagnostic

grouping, no one diagnostic class in DSM-IV comprehensively includes all of the

impulse control disorders. A number of disorders characterized by impulse

control problems are classified elsewhere (e.g., con-duct disorder,

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, opposi-tional-defiant disorder,

delirium, dementia, substance-related disorders, schizophrenia and other

psychotic disorders, mood disorders, antisocial and borderline personality

disorders). What ties together the disorders in this class is that they present

with clinically significant impulsive behavior and that they are not better

accounted for by one of the mental disorders included in other parts of

DSM-IV-TR. Five such disorders are included here: intermittent explosive

disorder, pathological gambling, pyroma-nia, kleptomania and trichotillomania.

Adjustment Disorders

All DSM-IV categories (except NOS categories) take

priority over adjustment disorder. This category is intended to apply to

maladaptive reactions to psychosocial stressors that do not meet the criteria

for any specific DSM-IV-TR disorder.

Personality Disorders

This diagnostic class is for personality patterns

that significantly deviate from the expectations of the person’s culture, are

perva-sive and lead to significant impairment or distress. Ten specific

personality disorders are included in DSM-IV: paranoid per-sonality disorder

(pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of oth-ers), schizoid personality

disorder (detachment from social re-lationships and a restricted expression of

emotions), schizotypal personality disorder (acute discomfort with close

relationships, perceptual distortions and eccentricities of behavior),

antisocial personality disorder (disregard for the rights of others),

border-line personality disorder (instability of personal relationships,

instability of self-image and marked impulsivity), histrionic per-sonality

disorder (extensive emotionality and attention seeking), narcissistic

personality disorder (grandiosity, need for admira-tion and lack of empathy),

avoidant personality disorder (social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy and

hypersensitivity to nega-tive evaluation), dependent personality disorder

(excessive need to be taken care of), and obsessive–compulsive personality

dis-order (preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and

personal control at the expense of flexibility, openness and efficiency).

Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

This section of DSM-IV is for problems that are not

mental disor-ders but that may be a focus of attention for treatment by a

mental health professional. Psychological

factors affecting medical con-dition is intended to allow the psychiatrist

to note the presence of psychological

factors (e.g., Axis I or II disorder) that adversely affect the course of a

general medical condition, including fac-tors that interfere with treatment and

factors that constitute health risks to the individual. Six specific medication-induced movement disorders are also included because of their impor-tance

in treatment and differential diagnosis; five are related to neuroleptic

administration and one (medication-induced postural tremor) is most often

associated with the use of lithium carbon-ate. Although these are best

considered medical conditions, by DSM-IV-TR convention they are coded on Axis

I.

Relational problems include parent–child, partner

and sibling relational problems. Relational problem related to a men-tal

disorder or general medical condition applies to situations in which one member

of the relational unit has a mental disorder or a general medical condition. In

such situations, the relational dynamics can negatively affect the individual’s

condition or vice versa (or both). Problems

related to abuse or neglect (physical abuse, sexual abuse and child

neglect.

Related Topics