Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychiatric Classification

DSM-IV Multiaxial System

DSM-IV OVERVIEW

The succeeding are organized according to the

presentation of disorders in the DSM-IV classification and provide detailed

information regard-ing the diagnosis, etiology and pathophysiology, epidemiology,

course and treatment of these DSM-IV disorders.

DSM-IV Multiaxial System

The multiaxial system was first introduced by

DSM-III in order to encourage the clinician to focus his or her attention

during the evaluation process on issues above and beyond the psychiatric

diagnosis. Use of the multiaxial system requires that informa-tion be noted on

each of the five different axes, each axis de-voted to a different aspect of

the evaluation process. Axes I, II and III are the diagnostic axes that divide

up the diagnostic pie into three separate domains. Axis I is for “clinical

syndromes and disordersg’’, an admittedly confusing name since Axis II and Axis

III are also diagnostic axes. The most accurate name for Axis I is “diagnoses

not coded on Axis II and Axis III’’, since Axis II and Axis III were carved out

of Axis I specifically to draw attention to certain disorders that clinicians

were more likely to overlook.

That said, Axis II is designated for coding

personality disorders and mental retardation. There have been many recent

criticisms of the coding of personality disorders on Axis II. Crit-ics

correctly point out that there is no firm conceptual basis for this division.

Although disorders on Axis II tend to be lifelong and pervasive, a number of

disorders on Axis I (e.g., schizophre-nia, autistic disorder, dysthymic

disorder) fit this description as well. Others have made the incorrect

assumption that categories on Axis II are unresponsive to medication treatment,

which is at odds with more recent evidence that medications are often help-ful

in the treatment of personality disorders. The fact is that the Axis I/Axis II

division was made strictly pragmatic. It was in-troduced in DSM-III as a way of

drawing attention to a set of disorders that were thought not to be given

adequate attention by mental health professionals. First introduced in DSM-III,

Axis II was designed to draw attention to certain disorders that were thought

to be overshadowed in the face of the more florid Axis I presentations..

Certainly the placement of personality disorders on a separate axis has

increased both their clinical visibility and their importance as a subject for

research studies. Whether the Axis I/Axis II division has finally outlived its

usefulness remains a topic of heated debate, and will be revisited during the

DSM-V deliberations.

Axis III, like Axis II, is intended to encourage

clini-cians to pay special attention to conditions that they tend to overlook;

in this case, clinically relevant general medical con-ditions. The concept of

“clinically relevant’’ is intended to be broad. For example, it would be

appropriate to list hyperten-sion on Axis III even if its only relationship to

an Axis I disor-der is its impact on the options for the choice of

antidepressant medication.

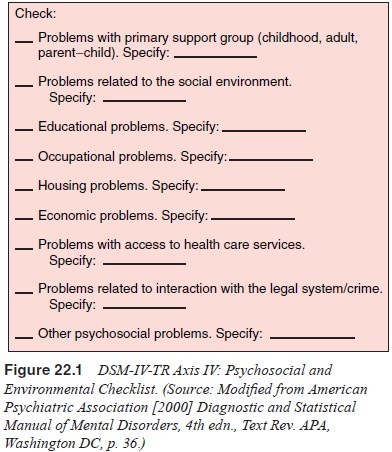

Psychosocial stressors are well known to play an

impor-tant role in the etiology, maintenance and management of a number of

mental disorders. Axis IV provides the psychiatrist with the opportunity to

list clinically relevant psychosocial and environmental problems (e.g.,

homelessness, poverty, divorce). To facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of

such problems, DSM-IV includes a psychosocial and environmental checklist that

allows the psychiatrist to indicate which types of problems are present and

relevant (Figure 22.1).

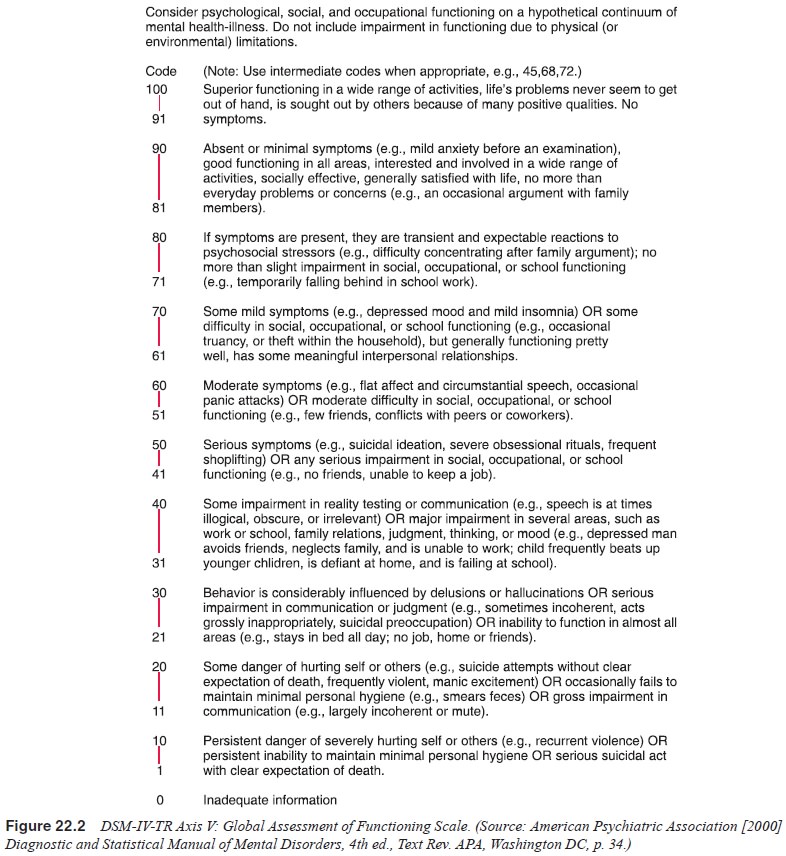

Mental disorders differentially impact on

individual’s level of functioning. For example, one patient with schizo-phrenia

may function quite well-being able to live in the com-munity, marry and have a

family, and maintain a steady job whereas another patient with schizophrenia

may function quite poorly, requiring chronic institutionalization. Since both

of these patients have symptoms that meet the diagnostic criteria for

schizophrenia, their important differences in functioning are not captured by

the clinical diagnosis alone. Some of the differences in functioning may be due

to different symptom profiles or symptom severities. Other differences may be

re-lated to resilience factors or different levels of psychosocial support.

Whatever the reason, the DSM-IV multiaxial system provides the clinician with

the ability to indicate the patient’s overall level of functioning in addition

to the diagnosis on Axis V, using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale

(Figure 22.2). This GAF Scale has been criticized because it is not actually a

“pure’’ measure of an individual’s ability to function, since it incorporates

symptom severity into the scale, for example, level 41 to 50 is for serious

symptoms (e.g., suicidal ideation, severe obsessional rituals, frequent

shop-lifting) or any serious impairment in social, occupational, or school

functioning (e.g., no friends, unable to keep a job). For this reason, the

DSM-IV includes a scale (the Social and Occu-pational Functioning Scale

[SOFAS]) that relies exclusively on functioning in its appendix of Criteria

Sets and Axes Provided for Further Study (American Psychiatric Association,

2000, pp. 817–818

Related Topics