Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Perspectives in Transcultural Nursing

Culturally Mediated Characteristics

Culturally Mediated Characteristics

Nurses should be aware

that patients act and behave in a variety of ways, in part because of the

influence of culture on behaviors and attitudes. However, although certain

attributes and attitudes are frequently associated with particular cultural

groups, as de-scribed in the following pages, it is important to remember that

not all people from the same cultural background share the same behaviors and

views. Although the nurse who fails to consider a patient’s cultural

preferences and beliefs is considered insensitive and possibly indifferent, the

nurse who assumes that all members of any one culture act and behave in the

same way runs the risk of stereotyping people. The best way to avoid

stereotyping is to view each patient as an individual and to find out the

patient’s cultural preferences. A thorough culture assessment using a cul-ture

assessment tool or questionnaire (see later discussion) is very beneficial.

SPACE AND DISTANCE

People tend to regard

the space in their immediate vicinity as an extension of themselves. The amount

of space they need between themselves and others to feel comfortable is a

culturally deter-mined phenomenon.

Because nurses and patients usually are not consciously aware of their personal space requirements, they frequently have diffi-culty understanding different behaviors in this regard.

For example, one patient may

perceive the nurse sitting close to him or her as an expression of warmth and

care; another patient may per-ceive the nurse’s act as a threatening invasion

of personal space. Research reveals that people from the United States, Canada,

and Great Britain require the most personal space between themselves and

others, whereas those from Latin America, Japan, and the Middle East need the

least amount of space and feel comfortable standing close to others.

If patients appear to position themselves too close or too far away, the

nurse should consider cultural preferences for space and distance. Ideally,

patients should be permitted to assume a position that is comfortable to them

in terms of personal space and distance. Because a significant amount of

communication during nursing care requires close physical contact, the nurse

should be aware of these important cultural differences and consider them when

de-livering care (Davidhizar, Dowd, & Newman-Giger, 1999).

EYE CONTACT

Eye contact is also a culturally determined behavior. Although most

nurses have been taught to maintain eye contact when speak-ing with patients,

some people from certain cultural backgrounds may interpret this behavior

differently. Some Asians, Native Americans, Indo-Chinese, Arabs, and

Appalachians, for example, may consider direct eye contact impolite or

aggressive, and they may avert their own eyes when talking with nurses and

others whom they perceive to be in positions of authority. Some Native

Americans stare at the floor during conversations, a cultural be-havior

conveying respect and indicating that the listener is paying close attention to

the speaker. Some Hispanic patients maintain downcast eyes as a sign of

appropriate deferential behavior toward others on the basis of age, gender,

social position, economic sta-tus, and position of authority. Being aware that

whether a person makes eye contact may be a result of the culture from which

they come will help the nurse understand a patient’s behavior and pro-vide an

atmosphere in which the patient can feel comfortable.

TIME

Attitudes about time

vary widely among cultures and can be a barrier to effective communication

between nurses and patients. Views about punctuality and the use of time are

culturally deter-mined, as is the concept of waiting. Symbols of time, such as

watches, sunrises, and sunsets, represent methods for measuring the duration

and passage of time (Giger & Davidhizar, 1999; Spector, 2000).

For most health care providers, time and promptness are ex-tremely

important. For example, nurses frequently expect patients to arrive at an exact

time for an appointment, despite the fact that the patient is often kept

waiting by health care providers who are running late. Health care providers

are likely to function accord-ing to an appointment system in which there are

short intervals of perhaps only a few minutes. For patients from some cultures,

how-ever, time is a relative phenomenon, with little attention paid to the

exact hour or minute. Some Hispanic people, for example, consider time in a

wider frame of reference and make the primary distinction between day and

night. Time may also be determined according to traditional times for meals,

sleep, and other activities or events. For people from some cultures, the

present is of the greatest importance, and time is viewed in broad ranges

rather than in terms of a fixed hour. Being flexible in regard to schedules is

the best way to accommodate these differences.

Value differences also

may influence a person’s sense of prior-ity when it comes to time. For example,

responding to a family matter may be more important to a patient than meeting a

sched-uled health care appointment. Allowing for these different views is

essential in maintaining an effective nurse-patient relationship. Scolding or

acting annoyed at a patient for being late undermines the patient’s confidence

in the health care system and might re-sult in further missed appointments or

indifference to health care suggestions.

TOUCH

The meaning people associate with touching is culturally deter-mined to

a great degree. In some cultures (eg, Hispanic, Arab), male health care

providers may be prohibited from touching or examining certain parts of the

female body. Similarly, it may be inappropriate for females to care for males.

Among many Asian Americans, it is impolite to touch a person’s head because the

spirit is believed to reside there. Therefore, assessment of the head or

evaluation of a head injury requires alternative approaches. The patient’s

culturally defined sense of modesty must also be considered when providing nursing

care. For example, some Jew-ish and Islamic women believe that modesty requires

covering their head, arms, and legs with clothing.

COMMUNICATION

Many aspects of care may be influenced by the diverse cultural

perspectives held by the health care providers, patient, family, or significant

others. One example is the issue of informed consent and full disclosure. In

general, a nurse may argue that patients have the right to full disclosure

about their disease and prognosis and may feel that advocacy means working to

provide that dis-closure. Family members of some cultural backgrounds may

be-lieve it is their responsibility to protect and spare the patient, their

loved one, the knowledge of a terminal illness. Similarly, patients may, in

fact, not want to know about their condition and may ex-pect their family

members to “take the burden” of that knowl-edge and related decision-making

(Kudzma, 1999). The nurse should not decide that the family or patient is

simply wrong or that the patient must know all details of his or her illness.

Simi-lar concerns may be noted when patients refuse pain medication or

treatment because of cultural beliefs regarding pain or belief in divine

intervention or faith healing. Determining the most ap-propriate and ethical

approach to patient care requires an explo-ration of the cultural aspects of

these situations. Self-examination by the nurse and recognition of one’s own

cultural bias and world view, as discussed earlier, will play a major part in

helping the nurse to resolve cultural and ethical conflicts. The nurse must

promote open dialogue and work with the patient, family, physi-cian, and other

health care providers to reach the culturally ap-propriate solution for the

patient.

OBSERVANCE OF HOLIDAYS

People from all cultures

celebrate civil and religious holidays. Nurses should familiarize themselves

with major holidays for members of the cultural groups they serve. Information

about these important celebrations is available from various sources, including

religious organizations, hospital chaplains, and patients themselves. Routine

health appointments, diagnostic tests, surgery, and other major procedures

should be scheduled to avoid those holidays a patient identifies as

significant. Efforts should also be made to accommodate patients and family or

significant others, when not contraindicated, as they perform holiday rituals

in the health care setting.

DIET

The cultural meanings associated with food vary widely but usu-ally

include one or more of the following: relief of hunger; pro-motion of health

and healing; prevention of disease or illness; expression of caring for

another; promotion of interpersonal closeness among individuals, families,

groups, communities, or nations; and promotion of kinship and family alliances.

Food may also be associated with solidification of social ties; celebra-tion of

life events (eg, birthdays, marriages, funerals); expression of gratitude or

appreciation; recognition of achievement or ac-complishment; validation of

social, cultural, or religious ceremo-nial functions; facilitation of business

negotiations; and expression of affluence, wealth, or social status.

Culture determines which

foods are served and when they are served, the number and frequency of meals,

who eats with whom, and who is given the choicest portions. Culture also

determines how foods are prepared and served; how they are eaten (with

chopsticks, hands, or fork, knife, and spoon); and where people shop for their

favorite food items (eg, ethnic grocery stores, spe-cialty food markets).

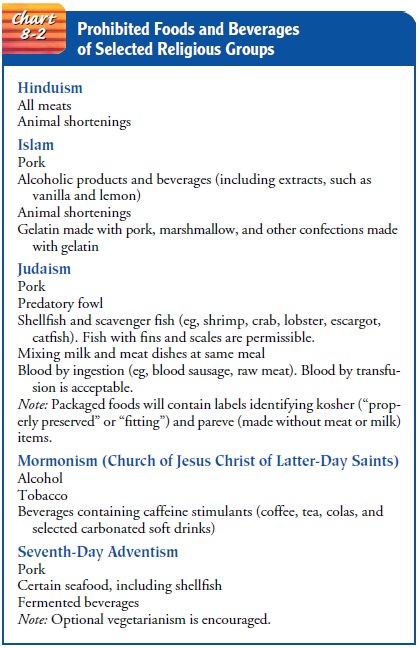

Religious practices may include fasting (eg, Mormons, Catholics,

Buddhists, Jews, Muslims), abstaining from selected foods at particular times

(eg, Catholics abstain from meat on Ash Wednesday and on Fridays during Lent),

and considerations for medications (eg, Muslims may prefer to use

non-pork-derived in-sulin). Practices may also include the ritualistic use of

food and beverages (eg, Passover dinner, consumption of bread and wine during

religious ceremonies). Chart 8-2 summarizes some dietary practices of selected

religious groups.

Many groups tend to feast, often in the company of family and friends, on selected holidays. For example, many Christians eat large dinners on Christmas and Easter and consume other traditional high-calorie, high-fat foods, such as seasonal cookies, pastries, and candies. These culturally-based dietary practices are especially significant in the care of patients with diabetes, hy-pertension, gastrointestinal disorders, and other conditions in which diet plays a key role in the treatment and health mainte-nance regimen.

BIOLOGIC VARIATIONS

Along with psychosocial adaptations, nurses must also consider the

physiologic impact of culture on patient response to treat-ment, particularly

medications. Data have been collected for many years regarding differences in

the effect some medications have on persons of diverse ethnic or cultural

origins. Genetic predispositions to different rates of metabolism cause some

pa-tients to be prone to overdose reactions to the “normal dose” of a

medication, while other patients are likely to experience a greatly reduced

benefit from the standard dose of the medication. An antihypertensive agent,

for example, may work well for a white male client within a 4-week time span but

may take much longer to work or not work at all for an African-American male

patient with hypertension. General polymorphism—variation in response to

medications resulting from patient age, gender, size, and body composition—has

long been acknowledged by the health care community (Kudzma, 1999). Culturally

competent medication administration requires that consideration of ethnicity

and related factors such as values and beliefs regarding the use of herbal

sup-plements, dietary intake, and genetic factors can affect the effec-tiveness

of treatment and compliance with the treatment regimen (Giger & Davidhizar,

1999; Kudzma, 1999).

COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Interventions for

alterations in health and wellness vary among cultures. Interventions most

commonly used in the United States have been labeled as conventional medicine by the Na-tional Institutes of Health (n.d.).

Other names for conventional medicine were allopathy, Western medicine, regular

medicine, mainstream medicine, and biomedicine. Interest in interven-tions that

are not an integral part of conventional medicine prompted the National

Institutes of Health to create the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) in

1992, and then to establish the National Center for Complementary and Alternative

Med-icine (NCCAM) in 1999.

The NCCAM grouped

complementary and alternative med-icine interventions into five main

categories: alternative medical systems, mind–body interventions, biologically

based therapies, manipulative and body-based methods, and energy therapies

(National Institutes for Health, National Center for Comple-mentary and

Alternative Medicine, accessed 9/8/01).

· Alternative medical

systems are defined as complete systemsof theory and

practice that are different from conventional medicine. Some examples are

traditional Eastern medicine (including acupuncture, herbal medicine, oriental

massage, and Qi gong); India’s traditional medicine, Ayurveda (in-cluding diet,

exercise, meditation, herbal medicine, mas-sage, exposure to sunlight, and

controlled breathing to restore harmony of an individual’s body, mind, and

spirit); homeo-pathic medicine (including herbal medicine and minerals); and

naturopathic medicine (including diet, acupuncture, herbal medicine,

hydrotherapy, spinal and soft-tissue ma-nipulation, electrical currents,

ultrasound and light therapy, therapeutic counseling, and pharmacology).

· Mind–body interventions are defined as techniques to facilitatethe mind’s ability to affect

symptoms and bodily functions. Some examples are meditation, dance, music, art

therapy, prayer, and mental healing.

· Biologically based

therapies are defined as natural and bio-logically

based practices, interventions, and products. Some examples are herbal

therapies (an herb is a plant or plantpart that produces and contains chemical substances

that act upon the body), special diet therapies (such as those of Drs. Atkins,

Ornish, and Pritikin), orthomolecular thera-pies (magnesium, melatonin,

megadoses of vitamins), and biologic therapies (shark cartilage, bee pollen).

· Manipulative and body-based methods are defined as

inter-ventions based on body movement. Some examples are chi-ropracty

(primarily manipulation of the spine), osteopathic manipulation, massage

therapy (soft tissue manipulation), and reflexology.

· Energy therapies are defined as interventions that focus

onenergy fields within the body (biofields) or externally (elec-tromagnetic

fields). Some examples are Qi gong, Reiki, therapeutic touch, pulsed

electromagnetic fields, magnetic fields, alternating electrical current, and

direct electrical current.

A patient may choose to seek an alternative to conventional medical or

surgical therapies. Many of these alternative therapies are becoming widely

accepted as feasible treatment options. Therapies such as acupuncture and

herbal treatments may be rec-ommended by a patient’s physician to address

aspects of a condi-tion that are unresponsive to conventional medical treatment

or to minimize side effects associated with conventional medical therapy. Alternative

therapy used to supplement conventional medicine may be referred to as complementary therapy.

Physicians and advanced

practice nurses may work in collab-oration with an herbalist or with a

spiritualist or shaman to pro-vide a comprehensive treatment plan for the

patient. Out of respect for the way of life and beliefs of patients from

different cultures, it is often necessary that the healers and health care

providers respect the strengths of each approach (Palmer, 2001). Complementary

therapy is becoming more common as health care consumers become more aware of

what is available through information in printed media and on the Internet.

As patients become more

informed, they are more likely to participate in a variety of therapies in

conjunction with their con-ventional medical treatments. The nurse needs to

assess each pa-tient for use of complementary therapies, remain alert to the

danger of conflicting treatments, and be prepared to provide information to the

patient regarding treatment that may be harmful. The nurse must, however, be

accepting of the patient’s beliefs and right to control his or her own care. As

a patient advocate, the nurse facili-tates the integration of conventional

medical, complementary, and alternative medical therapies.

Related Topics