Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: Tissues and Membranes

Connective Tissue

CONNECTIVE TISSUE

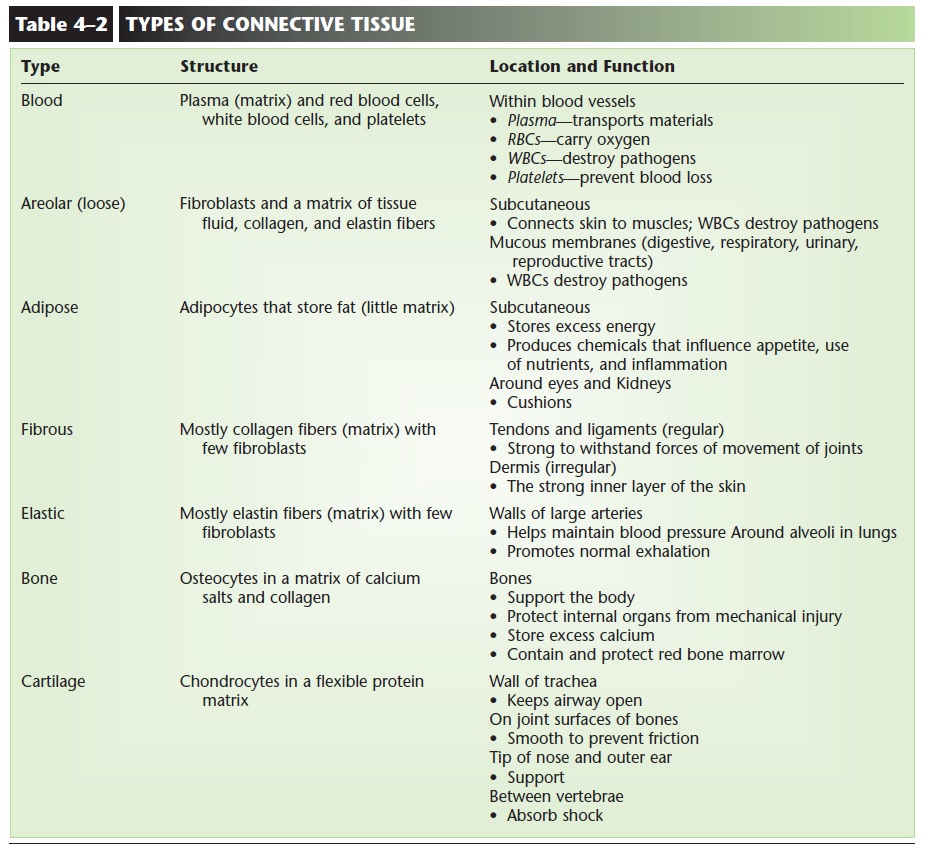

There are several kinds of connective tissue, some of which may at first seem more different than alike. The types of connective tissue include areolar, adipose, fibrous, and elastic tissue as well as blood, bone, and cartilage; these are summarized in Table 4–2. A char-acteristic that all connective tissues have in common is the presence of a matrix in addition to cells. The

Each connective tissue has its own specific kind of matrix. The matrix of blood, for example, is blood plasma, which is mostly water. The matrix of bone is made primarily of cal-cium salts, which are hard and strong. As each type of connective tissue is described in the following sec-tions, mention will be made of the types of cells pres-ent as well as the kind of matrix.

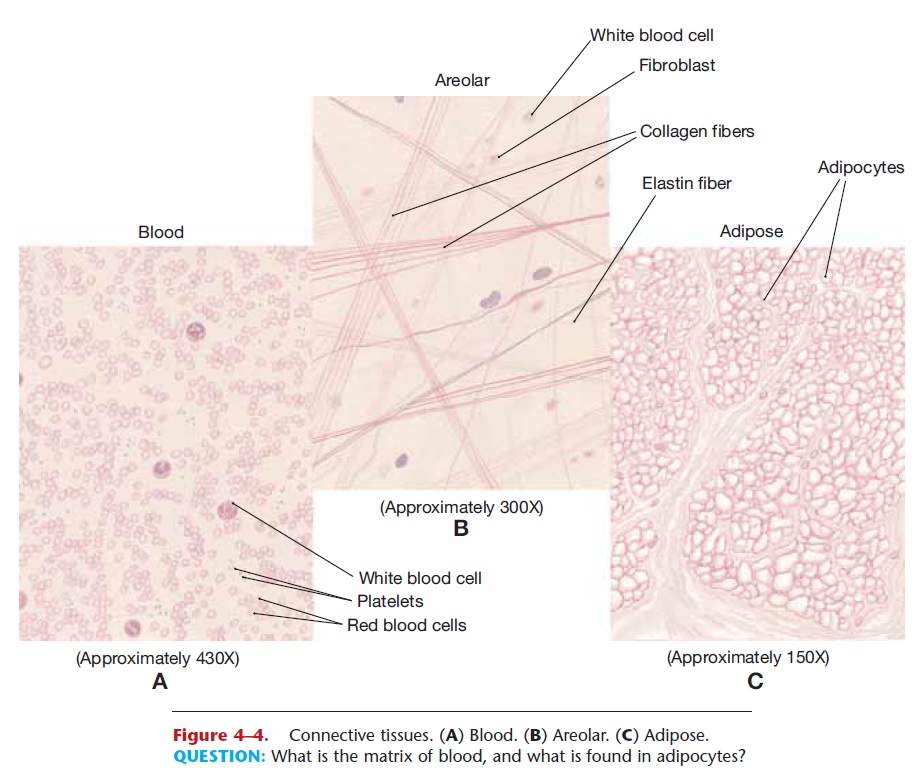

BLOOD

Blood consists of cells and plasma; cells are the living portion. The matrix of blood is plasma, which is about 52% to 62% of the total blood volume in the body. The water of plasma contains dissolved salts, nutrients, gases, and waste products. As you might expect, one of the primary functions of plasma is transport of these materials within the body.

Blood cells are produced from stem cells in the red bone marrow, the body’s primary hemopoietic tissue (blood-forming tissue), which is found in flat and irregular bones such as the hip bone and vertebrae. The blood cells are red blood cells, platelets, and the five kinds of white blood cells: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes (see Figs. 4–4 and 11–2). Lymphocytes mature and divide in lymphatic tissue, which makes up the spleen,

Figure 4–4. Connective tissues. (A) Blood. (B) Areolar. (C) Adipose.

QUESTION: What is the matrix of blood, and what is found in adipocytes?

the lymph nodes, and the thymus gland. The thymus also contains stem cells, but they produce only a subset of lymphocytes. Stem cells are present in the spleen and lymph nodes as well, though the number of lymphocytes they produce is a small fraction of the total.

The blood cells make up 38% to 48% of the total blood, and each type of cell has its specific function. Red blood cells (RBCs) carry oxygen bonded to the iron in their hemoglobin. White blood cells (WBCs) destroy pathogens by phagocytosis, the production of antibodies, or other chemical methods, and provide us with immunity to some diseases. Platelets prevent blood loss; the process of blood clotting involves platelets.

AREOLAR CONNECTIVE TISSUE

The cells of areolar (or loose) connective tissue are called fibroblasts. A blast cell is a “producing” cell, and fibroblasts produce protein fibers. Collagen fibers are very strong; elastin fibers are elastic, that is, able to return to their original length, or recoil, after being stretched. These protein fibers and tissue fluid make up the matrix, or non-living portion, of areolar con-nective tissue (see Fig. 4–4). Also within the matrix are mast cells that release inflammatory chemicals when tissue is damaged, and many white blood cells, which are capable of self-locomotion. Their importance here is related to the locations of areolar connective tissue.

Areolar tissue is found beneath the dermis of the skin and beneath the epithelial tissue of all the body systems that have openings to the environment. Recall that one function of white blood cells is to destroy pathogens. How do pathogens enter the body? Many do so through breaks in the skin. Bacteria and viruses also enter with the air we breathe and the food we eat, and some may get through the epithelial linings of the respiratory and digestive tracts and cause tissue dam-age. Areolar connective tissue with its mast cells and many white blood cells is strategically placed to inter-cept pathogens before they get to the blood and circu-late throughout the body.

ADIPOSE TISSUE

The cells of adipose tissue are called adipocytes and are specialized to store fat in microscopic droplets. True fats are the chemical form of long-term energy storage. Excess nutrients have calories that are not wasted but are converted to fat to be stored for use when food intake decreases. Any form of excess calo-ries, whether in the form of fats, carbohydrates, or amino acids from protein, may be changed to triglyc- erides and stored. The amount of matrix in adipose tissue is small and consists of tissue fluid and a few col-lagen fibers (see Fig. 4–4).

Most fat is stored subcutaneously in the areolar connective tissue between the dermis and the muscles. This layer varies in thickness among individuals; the more excess calories consumed, the thicker the layer.

Recent research has discovered that adipose tissue does much more than provide a cushion or store energy. Adipose tissue is now considered an endocrine tissue, because it produces at least one hormone. Leptin is an appetite-suppressing hormone secreted by adipocytes to signal the hypothalamus in the brain that fat storage is sufficient. When leptin secretion diminishes, appetite increases. Adipocytes secrete at least two chemicals that help regulate the use of insulin in glucose and fat metabo-lism. Adipose tissue is also involved in inflammation, the body’s first response to injury, in that it produces cytokines, chemicals that activate white blood cells. Our adipose tissue is not simply an inert depository of fat, rather it is part of the complex systems that ensure we are nourished properly or that protect us from pathogens that get through the skin.

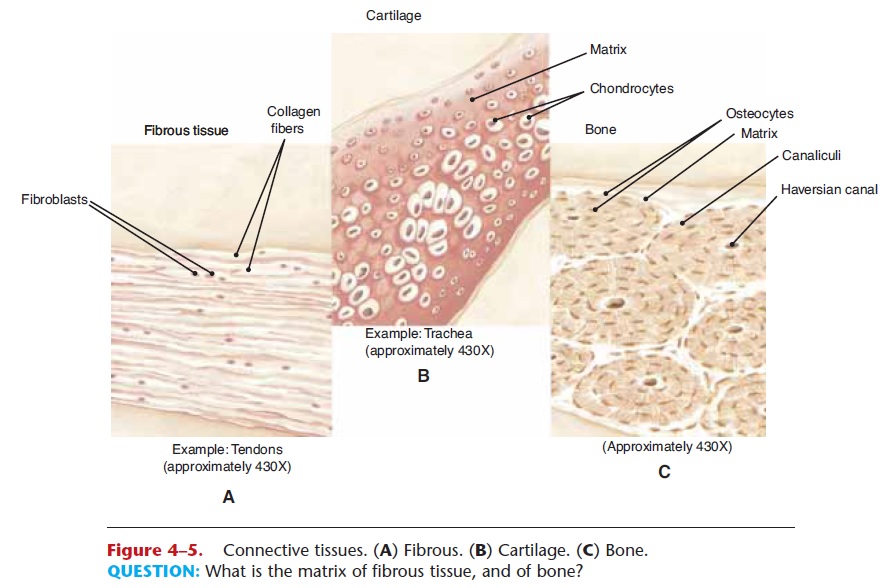

FIBROUS CONNECTIVE TISSUE

Fibrous connective tissue consists mainly of parallel (regular) collagen fibers with a few fibroblasts scat-tered among them (Fig. 4–5). This parallel arrange-ment of collagen provides great strength, yet is flexible. The locations of this tissue are related to the need for flexible strength. The outer walls of arter- ies are reinforced with fibrous connective tissue, because the blood in these vessels is under high pres-sure. The strong outer wall prevents rupture of the artery. Tendons and ligaments are made of fibrous connective tissue. Tendons connect muscle to bone; ligaments connect bone to bone. When the skeleton is moved, these structures must be able to withstand the great mechanical forces exerted upon them.

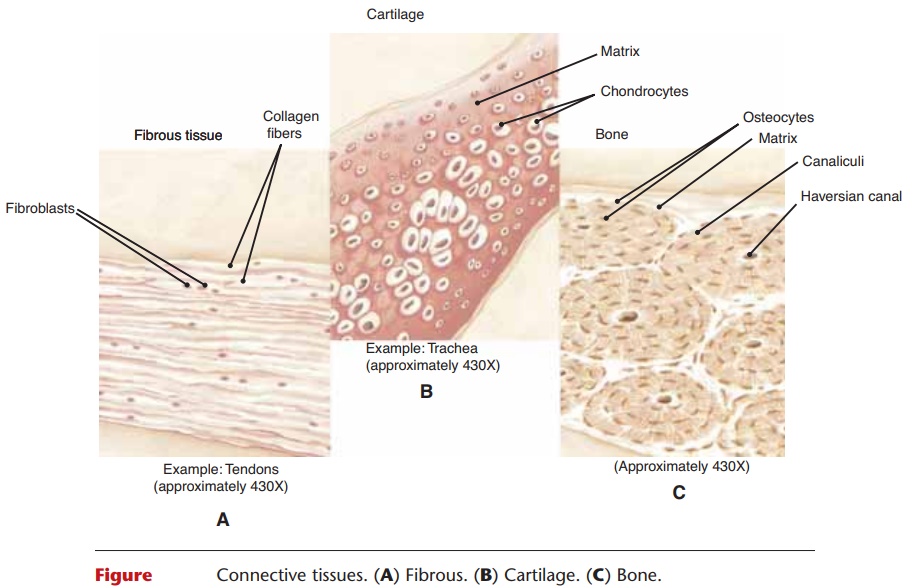

Figure 4–5. Connective tissues. (A) Fibrous. (B) Cartilage. (C) Bone.

Fibrous connective tissue has a relatively poor blood supply, which makes repair a slow process. If you have ever had a severely sprained ankle (which means the ligaments have been overly stretched), you know that complete healing may take several months.

An irregular type of fibrous connective tissue forms the dermis of the skin and the fasciae (membranes) around muscles. Although the collagen fibers here are not parallel to one another, the tissue is still strong. The dermis is different from other fibrous connective tissue in that it has a good blood supply.

ELASTIC CONNECTIVE TISSUE

As its name tells us, elastic connective tissue is pri-marily elastin fibers. One of its locations is in the walls of large arteries. These vessels are stretched when the heart contracts and pumps blood, then they recoil, or snap back, when the heart relaxes. This recoil helps keep the blood moving away from the heart, and is important to maintain normal blood pressure.

Elastic connective tissue is also found surrounding the alveoli of the lungs. The elastic fibers are stretched during inhalation, then recoil during exhalation to squeeze air out of the lungs. If you pay attention to your breathing for a few moments, you will notice that normal exhalation does not require “work” or energy. This is because of the normal elasticity of the lungs.

BONE

The prefix that designates bone is “osteo,” so bone cells are called osteocytes. The matrix of bone is made of calcium salts and collagen and is strong, hard, and not flexible. In the shafts of long bones such as the femur, the osteocytes, matrix, and blood vessels are in very precise arrangements called haversian systems or osteons (see Fig. 4–5). Bone has a good blood supply, which enables it to serve as a storage site for calcium and to repair itself relatively rapidly after a simple fracture. Some bones, such as the sternum (breastbone) and pelvic bone, contain red bone marrow, the primary hemopoietic tissue that produces blood cells.

Other functions of bone tissue are related to the strength of bone matrix. The skeleton supports the body, and some bones protect internal organs from mechanical injury.

CARTILAGE

The protein–carbohydrate matrix of cartilage does not contain calcium salts, and also differs from that of bone in that it contains more water, which makes it resilient. It is firm, yet smooth and flexible. Cartilage is found on the joint surfaces of bones, where its smooth surface helps prevent friction. The tip of the nose and external ear are supported by flexible cartilage. The wall of the trachea, the airway to the lungs, contains firm rings of cartilage to maintain an open air passageway. Discs of cartilage are found between the vertebrae of the spine. Here the cartilage is a firm cushion; it absorbs shock and permits movement. Within the cartilage matrix are the chondrocytes, or cartilage cells (see Fig. 4–5). There are no capillaries within the cartilage matrix, so these cells are nourished by diffusion through the matrix, a slow process.

This becomes clinically important when cartilage is damaged, for repair will take place very slowly or not at all. Athletes sometimes damage cartilage within the knee joint. Such damaged cartilage is usually surgically removed in order to preserve as much joint mobility as possible.

Related Topics