Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

Cognitive and Behavioral Treatment Strategies

Cognitive

and Behavioral Treatment Strategies

The

cognitive and behavioral therapies are well known for their use of specific

treatment techniques. Commonly used CBT procedures are directly linked to the

theoretical constructs and empirical research of this school of therapy.

Although techniques are given somewhat more emphasis in CBT than in other forms

of psychotherapy, there is still considerable room for therapists to be

creative and flexible in developing a treatment plan. In fact, nov-ice

therapists sometimes focus too much on applying techniques at the expense of

nurturing the therapeutic alliance and case for-mulation. Development of a

productive therapeutic relationship and an individualized case conceptualization

should always take precedence over the implementation of specific cognitive or

be-havioral techniques. A number of the more important CBT strat-egies are

described briefly here. More detailed accounts of CBT interventions can be

found elsewhere (Beck et al., 1979;

Beck 1995; Barlow and Cerny, 1988; Freeman et

al., 1989; Persons, 1989).

Collaborative Empiricism

The

therapeutic relationship is as important in CBT as in any of the other

effective psychotherapies. However, interchanges be-tween therapist and patient

often differ from those observed in supportive or dynamically oriented

treatment. One difference is that the therapist is responsible for managing the

pace of the ses-sion and uses an agenda to help make each session as efficient

as possible. Cognitive–behavioral therapists strive for a therapeutic

relationship that emphasizes: 1) a high degree of collaboration and 2) a

scientific attitude toward testing the validity or usefulness of particular

cognitions and behavior. This therapeutic stance is re-ferred to as

collaborative empiricism. The empirical nature of the relationship reflects

that therapist and patient work together as an investigative team to develop

hypotheses about cognitive or be-havioral patterns, examine data, and explore

alternative ways of thinking or behaving. At first, therapists usually spend

more time teaching and explaining in CBT than in other forms of therapy, yet in

the course of therapy, patients are actively engaged to be-come increasingly

involved in the work of treatment.

The

collaborative empirical stance requires that the thera-pist and patient work

together to make an honest appraisal

of the validity of cognitions as well as of the adaptive or maladaptive nature

of beliefs and behaviors. If a negative assessment proves to be accurate (e.g.,

the patient actually has made serious mistakes, the individual’s spouse is

highly likely to leave, or the patient has engaged in a repetitive

self-defeating behavior pattern), then the therapist and patient need to work

together in a problem-solving mode to develop a plan to cope with the problems

at hand or prac-tice more adaptive strategies for use in the future.

Wright

and Beck (1994) and others (Clark et al.

1999) have recommended several strategies for enhancing collaborative

empiricism. These include: 1) adjusting the therapist’s level of activity to

match the patients’ symptom severity or the phase of treatment; 2) encouraging

use of self-help procedures; 3) attend-ing to the “nonspecific” variables

important in all therapeutic relationships (e.g., empathy, respect, equanimity,

kindness and good listening skills); 4) promoting frequent two-way feedback; 5)

devising coping strategies to help deal with real losses or im-plementing a

plan of action to address maladaptive behavior; 6) recognizing transference

phenomena; 7) customizing thera-peutic interventions; and 8) using humor

judiciously. It is also important to recognize and account for the wide variety

of indi-vidual differences in cultural backgrounds, social attitudes and

expectations that each patient brings to the therapy encounter (Wright and

Davis, 1994).

Psychoeducation

Most

forms of CBT integrate explicit psychoeducational proce-dures as a core element

of the treatment process. Psychoeduca-tional procedures are typically blended

into treatment sessions in a manner that de-emphasizes formal teaching. There

is a con-certed effort to teach the patient why it is important to challenge

automatic thoughts, identify cognitive errors and practice imple-menting a more

rational thinking style. Behavioral interventions are also preceded by

psychoeducation to convey the background for principles such as extinction,

reinforcement, self-monitoring, exposure and response prevention.

In the

early phases of treatment, special attention is paid to socializing the patient

to CBT. The basic cognitive–behavioral model is demonstrated, and expectations

for both patient and ther-apist are conveyed. Some of the frequently used

psychoeducational procedures in CBT include brief, impromptu explanations

(often written on a chalkboard or a pad of paper to increase the chances of

comprehension and retention) and reading assignments, such as Coping with Depression (Beck and

Greenberg, 1974), Feel-ing Good (Burns,

1980), Mind Over Mood (Greenberger

and Padesky, 1995) or Getting Your Life Back (Wright and

Basco, 2001). Psychoeducational initiatives typically become more com-plex as

therapy proceeds. For example, detailed explanations and repeated exercises may

be needed before the patient fully grasps abstract concepts such as

attributional style or schemas. As ther-apy progresses, homework assignments

continue explicitly to re-inforce material covered during therapy sessions.

Modifying Automatic Thoughts

The first

step in changing automatic thoughts is to help the patient recognize when she

or he is having them. The therapist is oftenable to illustrate the presence of

automatic negative thoughts dur-ing the initial session by gently calling

attention to a change in the patient’s mood. Such “mood shifts” can be

excellent learning experiences that give personally relevant illustrations of

the link-age between cognitions and feelings.

One

common misconception of CBT is that its practition-ers disregard the role of

affect or feelings in the etiology and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

Actually, one of the principal components of CBT is the stimulation and

modulation of emotion (see Figure 69.3). In fact, Beck referred to emotion as

“the royal road to cognition” (Beck, 1991). In contrast to experiential

thera-pies, variations in emotion are used in CBT to establish links with

cognition and identify errors in information processing. Getting in touch with

feelings is thus not a goal in CBT but only a means by which therapy helps

patients to gain greater control over the processes that influence their moods

and behaviors.

Socratic Questioning

The most

frequently used technique to uncover and modify au-tomatic negative thoughts is

Socratic questioning (or guided discovery) (Beck et al., 1979; Overholser, 1993a, 1993b, 1993c). Socratic

questioning teaches the use of rationality and inductive reasoning to challenge

whether what is thought or felt is actu-ally true. The therapist models the use

of Socratic questioning and encourages the patient to start raising questions

about the validity of his or her thinking. There are few formal guidelines for

Socratic questioning (Overholser, 1993a). Rather, therapists learn to use their

experience and ingenuity to frame good ques-tions that engage the patient in a

process aimed at recognizing and modifying a biased or distorted cognitive

style. Typical ques-tions include: What ran through your mind at that time?

What is the evidence that your impression is accurate? Could there be any

alternative explanations? If this were true, what would be the worst thing that

would happen? When guided discovery methods are not sufficient to draw out

automatic thoughts, the therapist may turn to several alternative ways of

eliciting dysfunctional cognitions, as described in the following.

Imagery Techniques and Role-playing

Imagery

techniques and role-playing are used when direct ques-tioning does not fully

reveal important underlying cognitions. When imagery is used, the therapist

sets the scene by asking the patient to visualize the situation that caused

distress. Although some patients can readily imagine themselves in a previous

scene, many need prompts or imagery induction to encourage their ac-tive

participation in the exercise. Several types of questions can be used to help

frame the scene. These include inquiries about: 1) the physical details of the

setting, 2) occurrences immediately before the interaction, and 3) descriptions

of the other people in the scene (Wright and Beck, 1994). In role-playing

exercises, the therapist and patient act out an interpersonal vignette to

uncover automatic thoughts or to try out a revised pattern of thinking. This

technique is used less frequently than imagery by most cog-nitive–behavioral

therapists and may be reserved for situations in which transference distortions

are unlikely (Wright and Beck, 1994).

Thought Recording

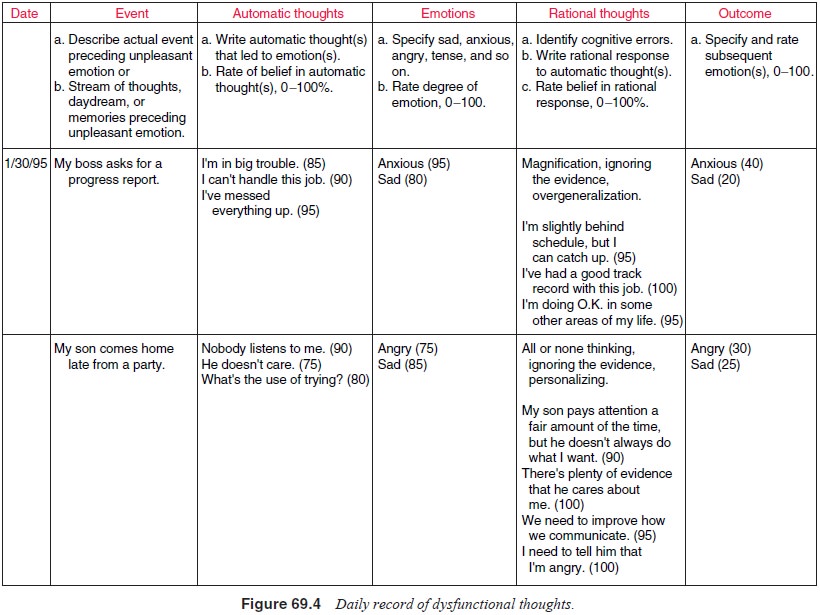

Thought

recording is one of the most useful procedures for iden-tifying and changing

automatic thoughts. This technique is first presented in relatively simple two-

or three-column versions in the early stages of therapy. When the two-column

procedure is used, patients are instructed to write down events in one column

and thoughts in the other. Alternatively, they can record events, thoughts and

emotions in the three columns. The purpose of this exercise is to encourage

patients to begin to use self-monitoring to increase awareness of their thought

patterns. Next, the strength of the emotion and the believability of the

automatic negative thoughts are rated on a scale of 0 to 100. In subsequent

sessions, a more complex five-column thought record, the Daily Record of

Dysfunctional Thoughts (DRDT) is introduced (Figure 69.4). The fourth column of

the DRDT encourages the patient to develop rational alternatives that rebut the

automatic negative thoughts; the fifth column is used for a reevaluation of the

mood and cog-nitive ratings. Work on identifying cognitive errors can also be

included in this form of thought recording.

Examining the Evidence

The

examining the evidence procedure is a collaborative exercise used to test the

validity of automatic negative thoughts. Cogni-tions are set forth as

hypotheses rather than established facts. The patient is encouraged to write

down evidence that either supports or refutes the automatic thought using a

two-column form (i.e., pros and cons). Cognitive errors such as magnification,

person-alization and all-or-nothing thinking are frequently revealed in these

situations.

Next, the

therapist helps to guide revision of the auto-matic negative thought in light

of the evidence (e.g., “I often feel

inferior to others, even when there’s no good evidence that they feel that way”

or “I have had a number of difficulties with my teachers and employers, but not

all relationships have been bad”). The process thus moves from the patient’s

general and globally negative interpretations to more specific, factually based

statements.

When an honest

appraisal uncovers evidence in support of negative cognitions, the therapist

may choose to focus on the patient’s attributions of causality or internality.

The patient who posits a negative attribution for poor work evaluation (e.g.,

“My performance was poor because I don’t have what it takes”) can usually be

aided to consider a more neutral attribution (e.g., “My performance was poor

because I was underprepared…my depression also prevented more energetic

preparation”). The treatment plan may also be revised to develop better methods

of coping in similar situations or to work on ways of remedi-ating skill

deficits. Sometimes, particular difficulties cannot be changed (e.g., physical

handicaps, markedly unattractive physi-cal looks, or severe financial

limitations).

Generating Alternatives

If automatic thoughts prove to be largely dysfunctional, the pa-tient is encouraged to generate alternatives that are more accu-rate or factual. Many of the techniques discussed earlier can be used to help generate alternatives to automatic thoughts. Socratic questioning is used in therapy sessions to help the patient start to think more creatively. Also, psychoeducational procedures may be employed to teach brainstorming techniques. For exam-ple, the patient may be taught to use “expert testimony” or the opinions of someone who knows her or him well (i.e., a sibling, spouse, or best friend) to help develop more rational alterna-tives. Thought records are often used to record alternatives to automatic thoughts. We often encourage patients to collect their thought records in notebook form for ongoing use. Figure 69.4 illustrates the use of rational alternatives during CBT for a de-pressed patient.

Many

patients with depression, anxiety and related conditions have relatively rigid

cognitive styles that perpetuate dysfunctional thought and behavior patterns.

These individu-als frequently experience “second-order” automatic negative

thoughts, that is, negative thoughts that are triggered by rational

alternatives (“that’s a cop-out…quit making excuses”). These thoughts about

thoughts tend to undermine the credibility of the rational responses and may

dampen the patient’s enthusiasm for using the procedure. The therapist may

notice a particular facial expression or a change in the patient’s posture that

suggests the existence of second-order thoughts. In such cases, more active

therapeutic assistance may be needed. For example, the therapist may need to act

as a teacher or coach in the area of adaptive cog-nitive functioning, rapidly

rebutting automatic thoughts as they arise. Coping cards, which are index cards

with helpful remind-ers on the use of CBT methods (in this case, rational

responses to repetitive automatic negative thoughts), may be written during

sessions and carried by the patient in his or her pocket, wallet, or purse for

later use.

Cognitive–Behavioral Rehearsal

Cognitive–behavioral

rehearsal is a treatment strategy that is par-ticularly useful for preparing

patients to put their experiences in CBT to work in real-life circumstances.

After automatic thoughts have been elicited and modified through procedures

described before, the therapist guides the patient in a series of rehearsalexercises

to try out alternative cognitions in a variety of situa-tions. By using imagery

and role-playing scenarios to practice generating more adaptive cognitions, the

patient may become aware of problems that could interfere with implementation

of the new style of thinking. Further practice and targeted homework

as-signments may then be needed before alternative cognitions can be fully

used. For example, the effects of cognitive–behavioral rehearsal may be

extended to real situations by assigning home-work to test use of the modified

automatic thoughts.

Modifying Schemas

The

emphasis in the early phases of therapy is usually on behavioral activation,

identifying and changing automatic thoughts, and the reduction of symptoms.

However, as the patient gains knowledge of cognitive–behavioral principles and

acute symptoms begin to subside, the focus of the treatment sessions usually

shifts toward work on the schema level. Because schemas serve as underlying

templates for making sense of new information, they play a major role in the

modulation of more superficial cognitions (automatic thoughts), regulation of

affect, self-esteem and control of the behavioral repertoire. Thus, schema

modification is an important component of cognitively oriented therapies.

With Axis

I disorders such as major depressive disorder and panic disorder, schema

revision efforts are directed at cor-recting dysfunctional attitudes that may

predispose the patientto symptomatic recurrences. After several months of

produc-tive therapy, schema modification may be placed in the context of

reducing future vulnerability. CBT of personality disorders typically requires

that a major portion of therapy be devoted to modifying schemas and related

patterns of behavioral dysfunc-tion (Beck et

al., 1990). When schematic work cannot be fully addressed in time-limited

therapy, the model of ongoing change may be introduced. Thus, the patient may

begin to change her or his “life course” by development of a long-term

self-help plan. Jarrett and colleagues (2001) have proposed continuation and

maintenance phases of CBT treatment of depression, and they argue for focusing

on schema change in these phases of treatment if it is not accomplished in the

acute phase of treatment.

Many of

the techniques used to test and modify auto-matic thoughts are also used to

identify and revise schemas. Psychoeducational interventions are usually

required as a first step. Most patients are not aware of their “guiding

principles”, so the therapist may need to begin by introducing and illustrat-ing

this concept. It is often useful to use synonyms for the term schema (such as

basic assumptions or core beliefs) and to dem-onstrate how schemas are linked

to automatic negative thoughts using material from the patient’s own experience

(Wright and Beck, 1994). Socratic questioning is the core procedure used for

schema modification (Beck et al.,

1979; Overholser, 1993c).

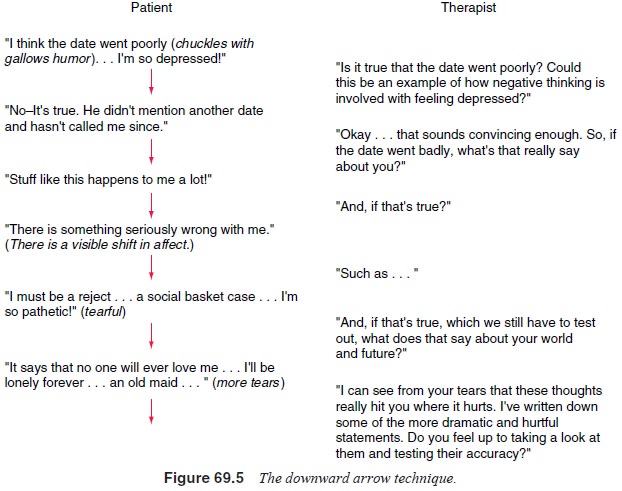

The

downward arrow technique (Figure 69.5) is a particu-larly powerful way to move

from surface cognitions to deeper cognitive structures (Thase and Beck, 1993).

This technique de-scribes asking the patient a question such as: “If this

automatic thought were true, what would it mean about you as a person?” Another

useful approach is to examine patterns of automatic thoughts from thought

records to sort out common themes. The therapist may suggest a thematic

collation based on her or his knowledge of the patient’s automatic negative

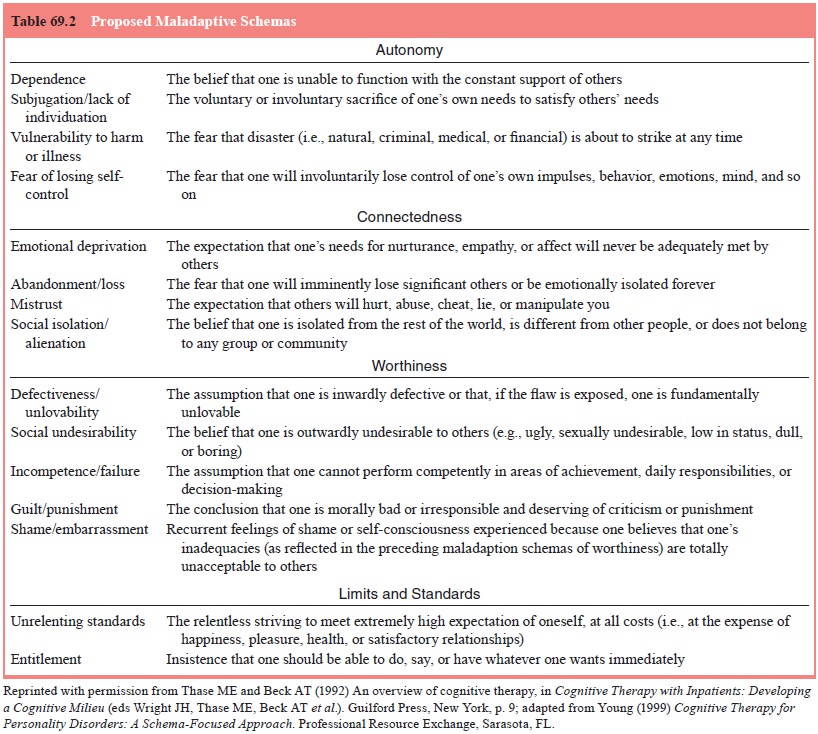

thoughts. In some

situations,

it may be helpful to have patients review a description of common pathological

schemas to recognize some of their core beliefs (see Table 69.2). On occasion,

it may be useful to have the patient write a brief autobiography to help

elucidate the historical antecedents of the schema. Computerized learning programs

can also be employed to help patients uncover their schemas (Wright et al., 1995, 2002a).

Because

schemas are so strongly held (in essence, they have helped define reality and

mold behavior for years), they may require intensive work in a number of therapy

sessions to undergo significant change. Sometimes long-term continuation and

maintenance CBT is required to accomplish schematic re-structuring. Therapists

can select from a number of CBT tech-niques, including examining the evidence,

listing advantages and disadvantages, generating alternatives, cognitive

response prevention and cognitive–behavioral rehearsal, as they attempt to

modify schemas (Wright and Beck, 1994). Examining the evidence, generating

alternatives and cognitive–behavioral re-hearsal were described earlier as

methods of changing automatic thoughts.

Cognitive Response Prevention

In cognitive response prevention, the patient agrees to complete a homework assignment in which she or he must behave in a way that is inconsistent with the pathological schema. For example, a person with perfectionistic attitudes may be engaged in an assign-ment in which she or he must perform in a “so-so” manner. This is intended to activate the schema which is triggering automatic negative thoughts (e.g., “They’ll think I’m a sloth” or “I’ll never be trusted with an important assignment again”). By not respond-ing to the perfectionistic demands dictated by the schema, the individual thus has the opportunity to cope with the automatic negative thoughts consequent to this “rule violation”.

Listing Advantages and Disadvantages

The

listing advantages and disadvantages procedure is particu-larly useful when a

schema appears to have both adaptive and maladaptive features. Schemas that

have damaging effects are often maintained because they also have a positive

side. For ex-ample, the schema “I must be perfect to be accepted” can have

significant benefits (e.g., hard work and attention to detail often lead to

success in work or school). Nevertheless, because perfec-tion is seldom

possible, the individual may remain vulnerable to setbacks. Other schemas, such

as “I’m a complete loser”, may not seem to have any advantages at first glance.

However, even such a markedly negative basic assumption can have certain

behavioral reinforcers associated with it. For example, a person who believes

that he or she is a loser may avoid making commitments, with-draw from

challenging assignments, or refuse to exert a sustained effort to solve a

difficult problem. This strategy may thus protect the person from painful

setbacks. The advantages and disadvan-tages analysis provides the patient and

therapist with essential in-formation for planning modifications. Revised

schemas are most likely to be used when they take into account both the

maladap-tive and the adaptive features of the old basic assumption.

In

general, it is recommended that patients keep a list of the schemas as they

have been identified. The schema list helps to focus the patient’s attention on

the overarching nature of these maladaptive principles. Because schemas often

become manifest only during periods of increased stress or symptom expression,

they may appear to fade in significance as the patient begins to improve. For

example, behavioral treatment programs that nei-ther endorse nor aim to modify

schemas are generally as effective as CBT in the short run. However, there may

be a false security engendered by symptom relief. The cognitive model posits

that the individual will remain vulnerable to the depressogenic im-pact of

“matching” life events unless schema revision is accom-plished (Thase and Beck,

1993).

Related Topics