Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

Behavioral Techniques

Behavioral

Techniques

In CBT,

behavioral methods are usually integrated with cogni-tive restructuring in a

comprehensive treatment plan. Behavioral strategies may be given a greater

emphasis earlier in therapy with more severely symptomatic patients such as

those with intense depression, bipolar symptoms, or schizophrenia (Beck et al., 1979; Thase and Wright, 1991;

Kingdon and Turkingdon, 1995; Basco and Rush, 1996; Scott and Wright, 1997).

Some cogni-tive–behavior therapists may rely primarily on behavioral

inter-ventions for conditions such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) or

simple phobias. Commonly used behavioral strategies are described here in

alphabetical order.

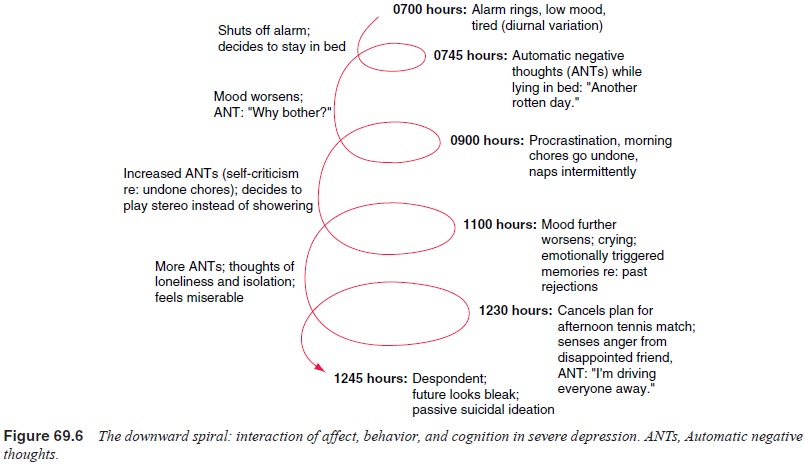

Activity Scheduling, Graded Tasks and Mastery–Pleasure Exercises

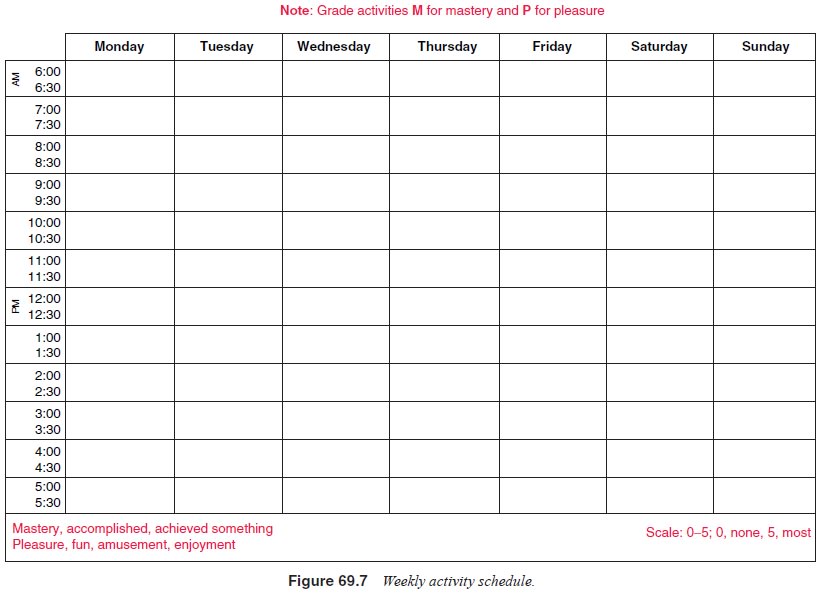

One key

to the behavioral approach for treatment of depression is the interruption of

the downward spiral linking mood, inactiv-ity and negative cognition (Beck et al., 1979; Lewinsohn et al., 1982) (Figure 69.6). Completing

an activity schedule is often the first behavioral homework assignment used in

CBT (Beck and Greenberg, 1974). Depressed patients are asked to begin to keep a

daily log that is used to chart the relationship between their moods and their

activities (Figure 69.7).

The

nature of the activities is examined, and deficits in activities that might

elicit pleasure or feelings of competence are identified. Next, assignments are

made to engage in discrete pleasurable activities (or, in the case of an

anhedonic individ-ual, activities that were rewarding before becoming

depressed). If needed, a “menu” of reinforcers can be generated by having the

patient fill out a Pleasant Events Schedule (Lewinsohn et al., 1982). Following operant principles, activities that have

been “high-grade” reinforcers in the past are scheduled during times of low

moods or decreased activity. Next, subjective ratings of

mastery

or competence and pleasure are added to the activity schedule by use of a

simple scale (i.e., 0–5), to avoid the tendency of dichotomous thinking. In

this way, achieving a small degree of pleasure or mastery during a scheduled

activity may be framed as an accomplishment, particularly early in the course

of therapy.

Breathing Control

An

important component of CBT for anxiety disorders involves teaching the patient

breathing exercises that may be used to counteract hyperventilation and/or

reduce tension (Clark et al., 1985).

Slow, deep breathing can have a calming effect not unlike progressive muscle

relaxation (Bernstein and Borkovec, 1973). These exercises also help to distract

the patient from autonomic cues. After initial instruction and practice, the

breathing skills are then applied in progressively more anxiety-provoking

situations.

A note of

caution is in order when teaching patients breath-ing control exercises. We

have seen many patients who have misunderstood instructions and who have

developed a pattern of deep overbreathing in response to stress. Instead of

helping reduce anxiety, their breathing changes may increase the chances of

hyperventilation. Thus, we typically recommend that patients be taught about

the pace and form of normal breathing patterns. Next clinicians can model

normal, calm breathing as compared with overbreathing during an anxiety attack.

The second hand of a watch can be used to time breaths so that they can be

slowed to a normal rate. Positive, calming images can also be used to reduce

anxiety during the breathing exercises. Finally, we suggest that patients

practice breathing exercises regularly to gain mastery of this anxiety

management technique.

Contingency Contracting and Behavior Exchange

These

strategies use the principles of operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938) to modify

the probability of occurrence of either undesired or desired behaviors. An

excellent introduction to these methods is presented by Malott and colleagues

(1993). One key to applied behavioral analysis is control over the

contingencies or reinforcers. Another important factor is that the terms of the

contract are negotiated and should be specific and relatively straightforward.

The positive contingency or reinforcer should be desirable and available

shortly after the terms of the contract have been met. A paycheck is a good

example of a contingency contract. Another common strategy is to chain, or

pair, a high-frequency behavior (e.g., reading, watching television, or

listening to music) to a low-frequency one (e.g., doing paperwork, doing

housework, spending time with the children). Contingencies should generally

start out relatively “rich” (e.g., 1 hour of video game time after 15 minutes

of paperwork) and may be progressively “thinned” in time (Malott et al., 1993). Punishments or “response

cost” contingencies are less widely used because of their negative affective

responses (Azrin and Holz, 1966).

Behavioral

contracts may be particularly useful for assisting patients with medication

adherence. For example, thetherapist may help the patient identify barriers to

taking medica-tion as prescribed and then work out behavioral solutions which

are written in contract form. Behavioral methods may include pairing medication

taking with routine activities such as brush-ing teeth or meals, reminder

systems and reinforcement from sig-nificant others. We recommend explicit

discussion of adherence problems and mutual agreement on a plan for taking

medications when patients have difficulty in following the pharmacotherapy

plan.

Desensitization and Relaxation Training

Systematic

desensitization (Wolpe, 1958) was one of the first behavioral strategies to

gain wide acceptance. Systematic desensitization relies on exposure through a

progressive hierarchy of fear-inducing situations. This procedure may use

pairing of progressive deep muscle relaxation and visualization of the target

behavior to decondition fearful responses. Systematic desensitization is useful

for treatment of simple phobias, social phobia, panic attacks and generalized

anxiety (Wolpe, 1982). Some evidence suggests that the active ingredient of

systematic desensitization is exposure to the feared situation, first in imagination

and later in reality, rather than an actual counterconditioning through the

relaxation response (Kazdin and Wilcoxin, 1976). Progressive deep muscle

relaxation is also useful as a self-directed coping strategy and for treatment

of sleep-onset insomnia (Goldfried and Davison, 1994; Bernstein and Borkovec,

1973).

Exposure and Flooding

The

purpose of these strategies is to speed extinction of conditioned fear or

anxiety responses. Behavioral theory dictates that fearfulness is reinforced by

avoidance and escape behaviors (Rachman et

al., 1986). Because the basis of the fear or phobia is irrational, the

optimal strategy is to increase exposure to the feared activity without

aversive consequences. In obsessive–compulsive disorder, the ritualistic behavior

(e.g., handwashing or checking) is presumed to be reinforced by the relief of

the anxiety associated with the compulsion (e.g., handwashing temporarily

relieves the fear of contamination) (Rachman et al., 1986). In exposure, there are at least three means of fear

reduction: autonomic habituation, recognition that the fear is irrational and

explicit enhancement of morale or self-efficacy that accompanies mastering the

previously dreaded activity.

In graded

or progressive exposure, a hierarchy is estab-lished, ranging from least to

most anxiety-provoking situations. The individual is taught one or more ways to

cope with anxiety (e.g., relaxation or self-instruction), and with the help of

the ther-apist, the items on the hierarchy are worked through, one item at a

time. Mastery is predicated on maintaining a sufficient duration of exposure

for the fear to extinguish or dissipate. In some cases, imagery (exposure in vitro) is used before moving to

exposure to the actual feared stimulus. Exposure may also be enhanced by guided

support (i.e., the therapist’s presence during the session) or by use of coping

cognitions for the duration of the exposure exercise.

Flooding,

which relies on the same principles, dispatches with the hierarchical approach.

The individual is exposed to the maximal level of anxiety as quickly as

possible. The rationale for this accelerated approach is that it may hasten

autonomic habituation. To be effective, flooding needs to be accompanied by

response prevention. In response prevention treatment of OCD, the individual

agrees not to perform the compulsion de-spite strong urges to do so. Because

obsessions are more private than compulsions, there can be less certainty that

the individual has fully participated in response prevention exercises (Stern,

1978).

Simple

phobias may be rapidly treated by an accelerated form of exposure referred to

as participant modeling or contact desensitization. The therapist serves as a

supportive coach or guide and assists the patient through a progressively more

de-manding level of exposure to the feared situation. In most cases, lifelong

fears of air travel, tunnels, heights, matches, dogs, water, or insects can be

fully treated in a few hours of guided exposure.

Social Skills Training

Satisfactory

interpersonal relationships require a complex set of skills, including

reciprocity, respect for another’s opinion, appro-priate modulation of

self-disclosure, the tempered ability to yield on some occasions and to set

limits at other times, the natural use of social reinforcers, and the capacity

to express anger and re-solve conflicts in a constructive manner (Lewinsohn et al., 1982; Hersen et al., 1984). Many people with

psychiatric disorders suf-fer from either a state-dependent deterioration of

these social skills or lifelong deficits of such skills. Once established,

social skills deficits can increase the likelihood of experiencing stress-ful

life events as well as “turn off ” family members and other sources of social

support that may help to buffer people against stressors (Coyne et al., 1987).

Problems

as diverse as underassertiveness, temper “atta-cks”, excessive self-disclosure,

monopolistic conversational style, underreinforcement of significant others and

splitting (i.e., playing one against another) are amenable to social skills

train-ing. The methods employed include modeling (i.e., the therapist

demonstrates a more effective alternative approach), role-playing and role

reversal, behavior rehearsal and specific practice as-signments. Often, the

interpersonal anxiety and lack of self-confidence that go hand in hand with

social skills deficits lessen in response to successful mastery of targeted

assignments.

Thought Stopping and Distraction

Automatic

negative thoughts and repetitive, intrusive rumina-tions are sometimes too

intense to address with purely cogni-tive interventions. The technique of

thought stopping capitalizes on the individual’s ability to use a selectively

narrowed atten-tional focus to suppress the intrusive cognitions. For example,

a ruminative individual may be asked to visualize a large red “stop” sign,

including its octagonal shape and white lettering. The command “Stop!” is

paired with the image. The image and command are then used to interrupt a “run”

of ruminations. At first, the technique is practiced in sessions at times when

auto-matic thoughts or ruminations are mild. After initial success, the

technique is next applied to more intensely disturbing cognitions. For

individuals who find visualization difficult or ineffective, a rubber band may

be worn on the wrist as a distractor. In a manner similar to that described

before, the command “Stop!” is paired with a brisk snap of the rubber band.

Indications for Treatment

The

cognitive and behavioral therapies are indicated as pri-mary treatments for

adults suffering from several nonpsychotic, nonorganic disorders including

major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, panic disorder, social phobia,

OCD, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder and

bulimia nervosa (Wright et al.,

2002b). Cognitive and be-havioral therapies are also useful as adjunctive

treatments for patients with bipolar disorder (Basco and Rush, 1996; Basco and

Thase, 1998; Lam et al., 2000) and

schizophrenia (Mueser, 1998; Kingdon and Turkington, 1995; Senky et al., 2000). Although not extensively

studied, cognitive and behavioral therapies in-corporating coping skills

training and relapse prevention strate-gies may also improve the outcome of

individuals with substance abuse disorders (Wright et al., 2002b).

Cognitive

and behavioral therapies, like most other types of treatment, have not been

studied widely in patients with Axis II disorders. However, the CBT approach to

problem specifica-tion and explicit training in coping skills may be well

suited for treatment of individuals willing to work on changing these

ha-bitual, ingrained patterns of thinking and behavior (Beck et al., 1990). Specific

cognitive–behavioral formulations have been de-veloped for each of the

personality disorders, and modifications of CBT methods have been described for

working with patients with Axis II problems (Beck et al., 1990). Linehan’s model of CBT (dialectical behavior

therapy) has been shown to be effica-cious in reducing parasuicidal behavior in

patients with border-line personality disorder (Linehan et al., 1991, 1993).

Related Topics