Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

Cognitive Model

Cognitive

Model

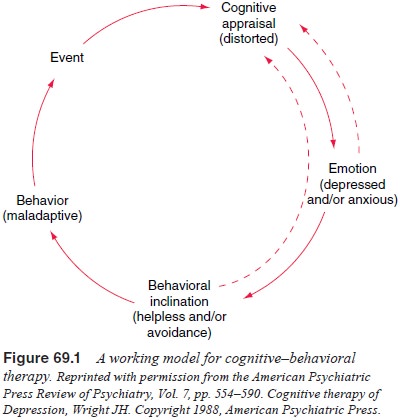

The basic

theories of the cognitive model are rooted in a long tradition of viewing

cognitions as primary determinants of emo-tion and behavior. For excellent

reviews of the historical bases of cognitive therapy, see Dobson and Block

(1988) Clark et al. (1999). The

description of cognitive theories given here is based largely on Beck’s

concepts. This model of therapy tends to give somewhat more emphasis to

cognitive than behavioral factors in treatment interventions, but both are

considered to be integral parts of the model (Figure 69.1).

Depending

on the case formulation and the phase of therapy, attention may be directed

primarily at cognitive or behavioral as-pects of the disorder. In most cases, a

combination of cognitive and behavioral techniques is used.

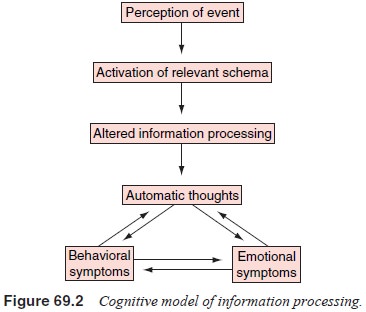

Figure

69.2 displays a simplified model for understanding the relationships between

environmental events, cognitions, emo-tion and behavior (Wright and Beck, 1994;

Wright, 1988; Thase and Beck, 1993). This model is based on the theoretical

assumptionthat environmental stimuli trigger cognitive processes and the

ensuing cognitions give the event personal meaning and elicit subsequent

physiological and affective arousal. These emotions, in turn, have a potent

reciprocal effect on cognitive content and information processing, such that

cascades of dysfunctional thoughts and emotions can occur. The individual’s

behavioral re-sponses to stimuli and thoughts are viewed as both a product and

a cause of maladaptive cognitions. Thus, treatment interventions may be targeted

at any or all components of the model.

Of

course, many other factors are involved in psychiatric disorders, including

genetic predisposition, state-dependent neuro-biological changes and various

interpersonal variables. These influ-ences are also included in the case

conceptualization in CBT. Wright and Thase (1992) have outlined an expanded

cognitive–biological model that can be used for synthesizing cognitive and

neurobiologi-cal factors in a combined therapy approach. Contemporary

psychi-atric research is striving to understand how best to combine and/or

sequence CBT and pharmacotherapy, and relate CBT technique to new

understandings in cognitive neuroscience. Nevertheless, the working model in

Figure 69.2 can be used as a practical template to guide the therapist’s case

formulation and interventions.

Automatic Thoughts and Schemas

Dysfunctional

information processing is apparent in many psychi-atric disorders at two major

levels of cognition–automatic thoughts and schemas (Beck, 1976; Dobson and

Shaw, 1986; Teasdale, 1983; Segal, 1988; Alfrod and Correia, 1994). Automatic

thoughts are cognitions that stream rapidly through an individual’s mind,

whether spontaneously or in response to some prompt or stimu-lus. Automatic

thoughts may be triggered by affective arousal (i.e., anger, anxiety, or

sadness), or conversely, affective shifts are gener-ally accompanied by

automatic negative thoughts (Teasdale, 1983). Their automatic nature refers to

their speed of entry into awareness and their implicit believability. In this

way, automatic thoughts have emotional validity (Thase and Beck, 1993). For

most people, before therapy, automatic thoughts are usually not examined

carefully for validity. In fact, many people susceptible to anxiety or

depression are likely to use an affectively focused logic referred to as

emotional reasoning (i.e., “I feel

that this is correct, therefore it is correct”). Although we all experience

automatic thoughts, in depression, anx-iety and other psychiatric disorders the

thoughts are distinguished by their greater intensity and frequency (LeFebvre,

1981).

Beck (1967) coined the term cognitive triad to describe the content of automatic negative thoughts. Typically, automatic negative thoughts may be grouped by themes pertaining to self, world (i.e., significant others or people in general) and future. As described subsequently, the themes revealed in one’s characteris-tic automatic negative thoughts may be used to infer deeper levels of cognition: beliefs, rules and schemas. Patients can be taught to examine their beliefs and their operational rules. Although pa-tients are not fully aware of their schemas, these cognitions are usually accessible through the questioning techniques used in CBT (Wright and Beck, 1994).

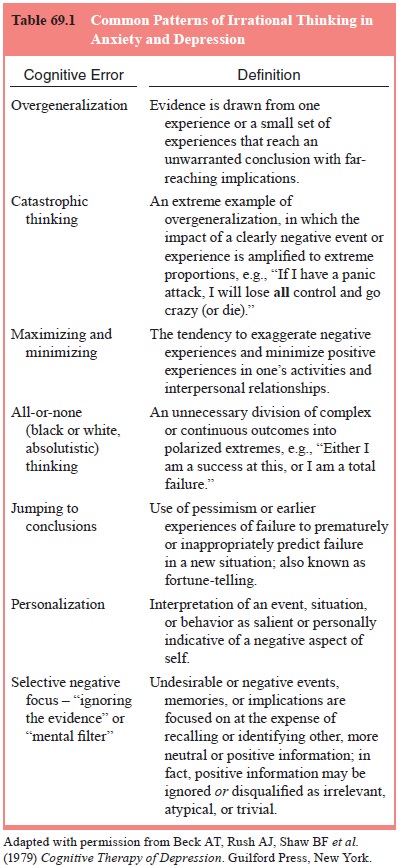

Beck and

coworkers (Beck et al., 1979; Beck

and Emery, 1985; Wright and Beck, 1983) have noted that stereotypic errors in

logic (termed cognitive errors or cognitive distortions) also shape the content

of automatic thoughts (Table 69.1).

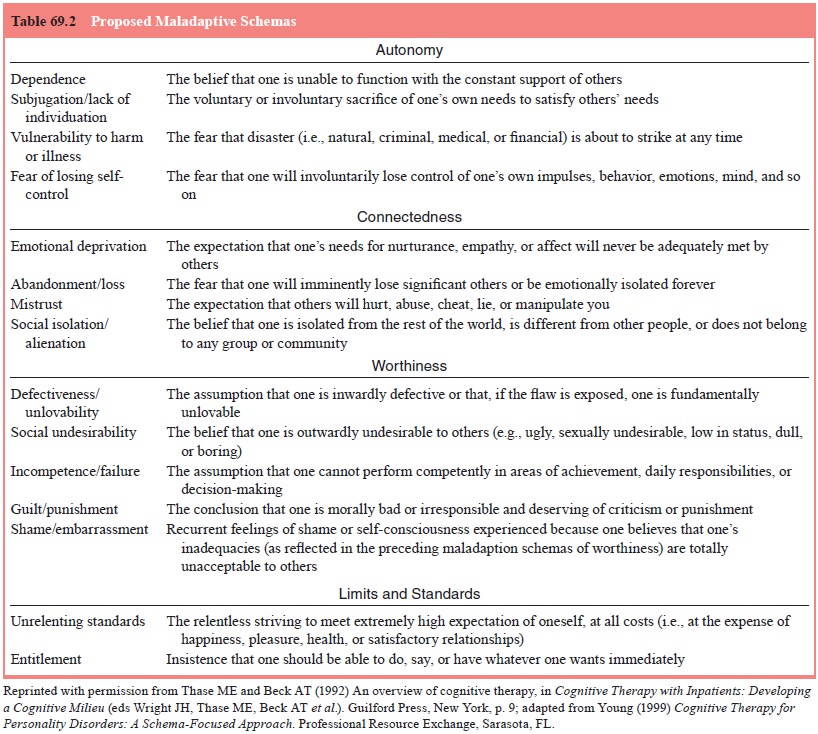

Schemas

represent the sum of one’s beliefs and attitudes. They are the basic

assumptions or unspoken rules that act as templates for screening and decoding

information from the environment (Segal, 1988; Wright and Beck, 1983; Young and

Lindermann,

1992). Psychological well-being may be understood in part by development of a

set of schemas that yield realistic appraisals of self in relation to world

(e.g., “I’m reasonably attrac-tive, but looks aren’t everything”, “I can be

loved under the right circumstances”, or “I must work harder to compensate for

an av-erage intellect”). Although unspoken, schemas may be inferred from one’s

beliefs and attitudes. In the cognitive model, dysfunc-tional attitudes are the

structural “bridge” between pathological schemas and automatic negative

thoughts. Schemas pertaining to safety, vulnerability to threat,

self-evaluation, one’s lovability, and one’s competence or self-efficacy

contain the ground rules for personal behavior that are particularly relevant

to the understand-ing of disorders such as anxiety, depression, or

characterological

disturbances

(Segal, 1988; Young and Lindermann, 1992; Blackburn et al., 1986b; Beck et al.,

1990). A number of schemas relevant to psychiatric illness are listed in Table

69.2. Bowlby (1985) has noted that most psychopathologically relevant sche-mas

are developed early in life, when the individual is relatively powerless and

dependent on caregivers.

The

cognitive model of psychiatric illness emphasizes the concept of stress-diathesis

(Thase and Beck, 1993; Metalsky et al.,

1987). From this perspective, a schema such as “I must be loved to have worth”, might remain latent until activated by a

relevant life stressor (i.e., a romantic breakup).

Underlying

schemas may be buttressed by either mala-daptive or adaptive attitudes (e.g.,

“No matter how hard I try, I’m bound to fail” versus “I’m a survivor; if I just

hang in there things will be okay”), but many of these cognitive structures

have mixed features (Wright and Beck, 1994). Schemas such as “If I’m not

perfect, I’m a failure” may lead to driven obsessional behav-ior, rigid

attitudes and beliefs, and frequent bouts of dysphoric or irritable moods.

However, basic perfectionistic beliefs such as these can also result in high

levels of performance and success.

The

concept of attributional style (Hammen et

al., 1989) describes an alternative view of cognitive vulnerability.

Derived from human studies of the learned helplessness para-digm (Seligman,

1975), attributional style refers to the charac-teristic way that people

explain the causality, controllability and impact of events. People susceptible

to depression are more likely to have an attributional style in which negative

events are per-ceived to be personally controllable (i.e., internality),

far-reaching (i.e., globality), and enduring (i.e., stability) (Peterson et al., 1985; Abramson et al., 1989; Sweeney et al., 1986).

The

results of many studies suggest that disturbances in information processing are

essential features of depression and anxiety.

Related Topics