Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Cognitive Psychology: Basic Theory and Clinical Implications

Cognitive Psychology: Basic Theory and Clinical Implications

Cognitive Psychology: Basic Theory and Clinical Implications

A number of factors, including the development of

complex learning theories, discussions regarding language development, use of

computers as a metaphor for human information process-ing and practical

applications needed during World War II, all contributed to the cognitive

revolution in psychological research during the 1950s and 1960s. Cognitive

psychology is now one of the major areas of psychological inquiry alongside

experimental, developmental, social and personality, and clinical psychologies.

The major synthesis of cognitive psychology with

clinical practice has been forged by cognitive–behavior therapists. There are,

however, other major applications and implications of cogni-tive psychology

regarding attention, memory and higher order cognitive processes such as

problem solving, schema construc-tion and modification, and automatic

processing.

The purposeful allocation of one’s finite mental

resources is a process known as attention (Ashcraft, 1994). Attentional

pro-cesses have profound implications regarding adaptive function-ing, inasmuch

as it falls to the attentional system to identify and select the most salient

pieces of information in need of processing at each moment. Inefficient or

erratic allocation of attention may engender maladaptive behavioral responses.

Furthermore, it has been noted that a subset of cognitive processes appears to

occur in the absence of attentional focus; such processes are often re-ferred

to as automatic (Posner and Snyder, 1975). Dysregulations of the attentional system

appear to play a central role in several clinical disorders, such as

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD),

Attention-Deficit/Hyper-activity Disorder (ADHD) and Borderline Personality

Disorder (BPD). Consequently, efficacious cognitive–behavioral interven-tions

for these disorders have accorded considerable attention to the development of

strategies designed to facilitate more efficient and adaptive functioning of

the attentional system.

Human memory is the central, essential ingredient

in an in-formation-processing system. Human cognition supports operations more

diverse by far than those of a computer, ranging from complex mathematical and

spatial reasoning, to artistic and literary endeav-ors, to athletic prowess and

interpersonal awareness. During the past century, empirical research has led to

an increasingly refined under-standing of the interlocking mechanisms of human

memory. This understanding has now been applied to the domain of clinical

assess-ment and psychopathology. Researchers have documented the role of memory

deficits and biases in several mental disorders, including (but not limited to)

depression and PTSD. The results of these inves-tigations have suggested that

memory, just as it plays an essential role in adaptive human functioning, may

also play a central role in mal-adaptive, pathological functioning. The

cognitive perspectives on psychopathology place an emphasis on the role of

schematic mem-ory bias in its contribution to various forms of psychiatric disorder,

and corresponding psychotherapy techniques have been developed to address bias

in memory (Beck, 1976; Beck et al.,

1979).

Problem solving is the complex mental process of

using previously learned information to identify solutions to new prob-lems.

Although specific empirical links between basic research and clinical practice

have been sparse, the conceptual connections have provided several clinical

procedures that are identifiable within self-control, cognitive–behavioral and

interpersonal psychotherapies.

Cognitive psychologists studying memory developed

the con-cept of schema, which can be understood as templates used to make sense

of and draw conclusions about new sensory affective, of cog-nitive information.

The schema construct was formulated to explain how memory is organized and why

it produces the inaccuracies and incompleteness often observed in human recall.

The incorporation and abstraction of new experiences into relevant schemata

serve to influence the interpretation of future experience and thereby the

en-coding and recollection of new memories. Schemata, therefore, affect all

levels of human cognitive processing and may well be the most significant

regarding a theoretical model contribution to date in cog-nitive psychology.

The development and modification of schemata are central to Beck and others’

models of cognitive–behavioral con-ceptualizations of psychopathology and

therapeutic change.

Finally, material is frequently processed

automatically while conscious processing occurs on a parallel cognitive track.

This raises intriguing questions regarding the similarities and differences in

various conceptualizations of the unconscious. Answers to questions raised

about automatic processes may well be the most significant future contributions

cognitive psychology and neuroscience integration can offer clinical practice.

Piaget’s work in the mid-20th century helped

delineate the subsequent areas of inquiry about human psychological functioning

and adaptation, and to some extent it has influenced the mainstream of

cognitive psychology; however, his greatest legacy is clearly his seminal

contributions to the study of human development and developmental psychology,

of which cognitive development is only a portion. The focus of Piaget’s theory was

also considered cognitive when set in apposition to Freud’s fo-cus on emotion

in his theory of psychosexual development.

Although the information-processing paradigm is

still dominant in cognitive psychology, two new paradigms became influential

during the last 10 to 15 years of the last century. The more established one is

called connectionism (McClelland et al., 1986). This approach addresses

an inherent limitation of the traditional computer metaphor of the mind – the

fact that the brain’s infor-mation processing operations differ dramatically

from those of serial symbol-processing computers, inasmuch as the former oc-cur

within a distributed architecture of parallel interconnected elemental (neural)

arrays. In other words, the connectionist ap-proach attempts to gain insights

into human information process-ing by attending closely to the manner in which

the brain’s own neurons process information. Accordingly, this approach uses

neural network computational modeling techniques (simulations) as useful

theoretical tools in the specification of the actual neural mechanisms and

processes that underlie human cognition.

An even newer cognitive paradigm is the so-called

eco-logical approach, although it is not yet as well established or as

conceptually coherent as are the information-processing and connectionist

paradigms. The ecological approach emphasizes that cognition does not occur in

isolation from larger environ-mental (e.g., cultural) contexts, and argues that

it is essential to study cognition in the natural context in which it occurs.

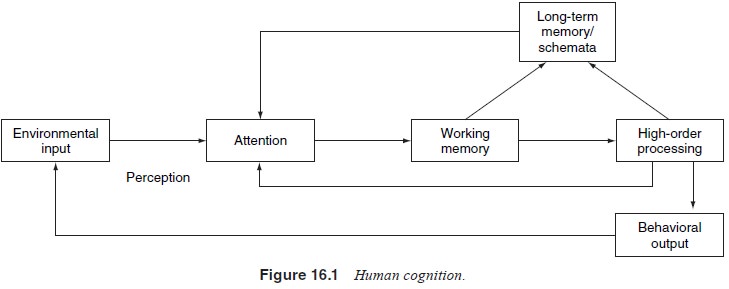

In the following sections, we review the general

findings regarding attention, memory and higher order cognitive pro-cesses and

give examples of their application to various areas of psychopathology and

treatment interventions. Figure 16.1 pro-vides an overall schematic of the

interactions of the cognitive processes that are discussed.

Related Topics