Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Postanesthesia Care

Circulatory Complications

CIRCULATORY

COMPLICATIONS

The most

common circulatory disturbances in the PACU are hypotension, hypertension, and

arrhyth-mias. The possibility that the circulatory abnor-mality is secondary to

an underlying respiratory disturbance should always be considered before any

other intervention, especially in children.

Hypotension

Hypotension is usually due to

relative hypovolemia, left ventricular dysfunction, or, less commonly, excessive

arterial vasodilatation. Hypovole-mia is by far the most common cause of

hypotension in the PACU. Absolute hypovolemia can result from inadequate

intraoperative fluid replace-ment, continuing f ulid sequestration by tissues

(“third-spacing”), wound drainage, or hemorrhage. Vasoconstriction during

hypothermia with central sequestration of intravascular volume may mask

hypovolemia until the patient’s temperature begins to rise again; subsequent

peripheral vasodilation during rewarming unmasks the hypovolemia and results in

delayed hypotension. Relative hypovole-mia is often responsible for the

hypotension associ-ated with spinal or epidural anesthesia (especially in the

setting of concomitant general anesthesia), venodilators, and α-adrenergic blockade: the venous

pooling reduces the effective circulating

blood volume, despite an otherwise normal

intra-vascular volume . Hypotension associated with sepsis and allergic

reactions is usu-ally the result of both hypovolemia and vasodila-tion.

Hypotension from a tension pneumothorax or cardiac tamponade is the result of

impaired venous return to the right atrium.Left ventricular dysfunction in

previously healthy persons is unusual, unless it is associated with severe

metabolic disturbances (hypoxemia, acidosis, or sepsis). Hypotension due to

ventricu-lar dysfunction is primarily encountered in patients with underlying

coronary artery or valvular heart disease or congestive heart failure and is

usually precipitated by fluid overload, myocardial ischemia, acute increases in

afterload, or arrhythmias.

Treatment of Hypotension

Mild hypotension during recovery from

anesthesia is common and typically does not require intensive treatment.

Significant hypotension is often defined as a 20% to 30% reduction in blood

pressure below the patient’s baseline level and usually requires cor-rection.

Treatment depends on the ability to assess intravascular volume. An increase in

blood pres-sure following a f luid bolus (250–500 mL crystal-loid or 100–250 mL

colloid) generally confirms hypovolemia. With severe hypotension, a

vasopres-sor or inotrope (dopamine or epinephrine) may be necessary to increase

arterial blood pressure until the intravascular volume deficit is at least

partially corrected. Signs of cardiac dysfunction should be sought in patients

with heart disease or cardiac risk factors. Failure of a patient with severe

hypotension to promptly respond to initial treatment mandates invasive

hemodynamic monitoring, or, better still, echocardiographic examination;

manipulations of cardiac preload, contractility, and afterload are often

necessary. The presence of a tension pneumo-thorax, as suggested by hypotension

with unilater-ally decreased breath sounds, hyperresonance, and tracheal

deviation, is an indication for immediate pleural aspiration, even before

radiographic confir-mation. Similarly, hypotension due to cardiac tam-ponade,

usually following chest trauma or thoracic surgery, often necessitates

immediate pericardiocen-tesis or surgical exploration.

Hypertension

Postoperative hypertension is common in the

PACU and typically occurs within the first 30 min after admission. Noxious

stimulation from inci-sional pain, endotracheal intubation, or bladder

distention is usually responsible. Postoperative hypertension may also reflect

the neuroendocrine stress response to surgery or increased sympathetic tone

secondary to hypoxemia, hypercapnia, or met-abolic acidosis. Patients with a

history of hyperten-sion are likely to develop hypertension in the PACU, even

in the absence of an identifiable cause. Fluid overload or intracranial

hypertension may also occasionally present as postoperative hypertension.

Treatment of Hypertension

Mild hypertension generally does not require

treat-ment, but a reversible cause should be sought. Marked hypertension can

precipitate postopera-tive bleeding, myocardial ischemia, heart failure, or

intracranial hemorrhage. Although decisions to treat postoperative hypertension

should be indi-vidualized, in general, elevations in blood pressure greater than

20% to 30% of the patient’s baseline, or those associated with adverse effects

such as myo-cardial ischemia, heart failure, or bleeding, should be treated.

Mild to moderate elevations can be treated with an intravenous β-adrenergic blocker, such as labetalol,

esmolol, or metoprolol; an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, such as

enalapril; or a calcium channel blocker, such as nicardip-ine. Hydralazine and

sublingual nifedipine (when administered to patients not receiving β-blockers) may cause tachycardia and

myocardial ischemia and infarction. Marked hypertension in patients with

limited cardiac reserve requires direct intraarterial pressure monitoring and

should be treated with an intravenous infusion of nitroprusside, nitroglycerin,

nicardipine, clevidipine, or fenoldopam. The end point for treatment should be

consistent with the patient’s own normal blood pressure.

Arrhythmias

Respiratory disturbances, particularly

hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and acidosis, will commonly be associ-ated with cardiac

arrhythmias. Residual effects from anesthetic agents, increased sympathetic

nervous system activity, other metabolic abnormalities, and preexisting cardiac

or pulmonary disease also pre-dispose patients to arrhythmias in the PACU.

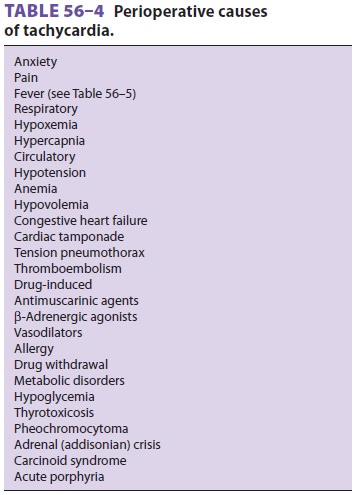

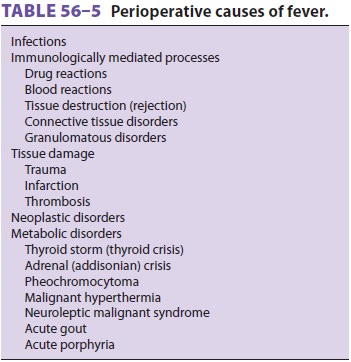

Bradycardia often represents the residual

effects of cholinesterase inhibitors, opioids, or β-adrenergic blockers. Tachycardia may represent the effect of an

anticholinergic agent; a β-agonist, such as albuterol; reflex tachycardia from hydralazine; and

more com-mon causes, such as pain, fever, hypovolemia, and anemia.

Anesthetic-induced depression of barore-ceptor function makes heart rate an

unreliable mon-itor of intravascular volume in the PACU.

Premature atrial and ventricular beats often

represent hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, increased sympathetic tone, or, less

commonly, myocardial ischemia. The latter can be diagnosed with a 12-lead ECG.

Premature atrial or ventricular beats noted in the PACU without discernable

cause will often also be found on the patient’s preoperative ECG, if one is

available. Such patients with a preexisting history of extrasystoles may or may

not have a history of palpitations or other symptoms, and previous car-diology

evaluation often has found no definitive cause. Supraventricular

tachyarrhythmias, including paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial

flut-ter, and atrial fibrillation, are typically encountered in patients with a

history of these arrhythmias and are more commonly encountered following

thoracic surgery.

Related Topics