Chapter: Microbiology and Immunology: General Microbiology: History of Microbiology

Chemotherapeutic Agents

Chemotherapeutic Agents

Until the 1930s, there had been no chemical treatment avail-able to fight bacterial infections in general. Prevention was the main means of protecting patients, and an obsession with the threat of germs and the moral responsibility to avoid infection was deeply instilled in Western cultures. At the same time, there were repeated hopes for a wonder drug. Louis Pasteur’s pupil Paul Vuillemin coined the term “antibiosis” in 1889 to denote a process by which life could be used to destroy life.

Paul Ehrlich was an exceptionally gifted histological chemist and invented the precursor technique to Gram-staining of bac-teria. He demonstrated that dyes react specifically with various components of blood cells and the cells of other tissues. He began to test the dyes for therapeutic properties to determine whether they could kill the pathogenic microbes. He developed Salvarsan, an arsenical compound in 1909. The compoundknown as “magic bullet” was capable of destroying T. pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis. This treatment proved effective against syphilis. This work was of epochal importance, stim-ulating research that led to the development of sulfa drugs, penicillin, and other antibiotics. He, therefore, is known as the father of chemotherapy.

Antibiotics

The word “antibiotic” did not follow immediately, but the drug pyocyanase, a weakly effective antibiotic, was marketed from the late nineteenth century into the 1930s. Early in the 1920s, there was an excitement about the potential of the newly identified phage viruses to kill bacteria. The discovery of an antibacterial factor in the exudates of the fungus Penicillium by Sir Alexander Fleming at St. Mary’s Hospital in 1928 was there-fore not totally unexpected. He accidentally discovered that a substance produced by the fungus destroyed the pyogenic bacteria, staphylococci. This initiated the beginning of the anti-biotics era. Other similar antibiotics were discovered in rapid succession. The sulfonamide drugs discovered subsequently offered cures for a wide range of bacterial infections.

Introduction of antibiotics in medicine raised a lot of expec-tations among both doctors and patients. Certain terrifying infectious diseases (e.g., rheumatic fever, syphilis, pneumonia, tuberculosis) and unpleasant skin conditions (e.g., carbuncles) became easily treatable, and their disappearance appeared to be certain. Surgeons could risk more dangerous operations and the use of drugs that compromised immune systems. Patients who had once turned to many kinds of alternative medicine, or refused treatment, now entrusted themselves to antibiotics.

Medical uses of antibiotics on human patients were harder to limit—even though, from the 1940s, the fear that public enthusiasm would promote the selection of resistant strains did lead—to some constraints. In Britain, the Penicillin Act of 1948 was explicitly intended to, for the first time, limit through prescription the public’s access to a drug that was not a poison. Nonetheless, during the 1950s, a penicillin-resistant strain of staphylococcus aureustermed 80/81 infected hospitals and mater-nity wards across the world. Newborn babies in hospital crèches were infected and postoperative infections proved common.

By the late 1990s, although many variants of older drugs had been produced, new families of antibiotics were, however, not being discovered. However, a sustained effort is now being made to develop more effective antibiotics to treat a wide range of infections.

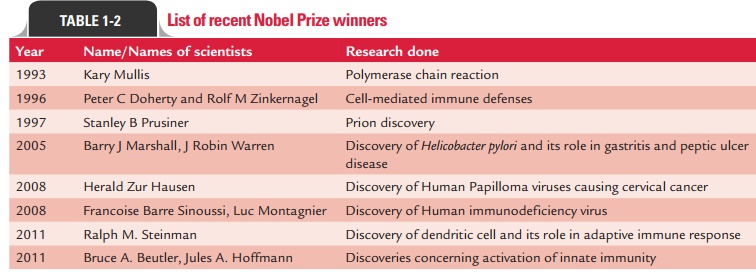

The field of medical microbiology has been enriched by contributions of many eminent microbiologists both in the past and in the recent times. The work of many of them has been recognized worldwide by the award of Nobel Prizes (Table 1-2).

Related Topics