Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Nutrition in Perioperative & Critical Care

Basic Nutritional Needs

BASIC NUTRITIONAL NEEDS

Maintenance of normal body mass, composition, structure, and function

requires the periodic intake of water, energy substrates, and specific

nutrients. Nutri-ents that cannot be synthesized from other nutrients are

characterized as “essential.” Remarkably, relatively few essential nutrients

are required to form the thou-sands of compounds that make up the body. Known

essential nutrients include 8–10 amino acids, 2 fatty acids, 13 vitamins, and

approximately 16 minerals.

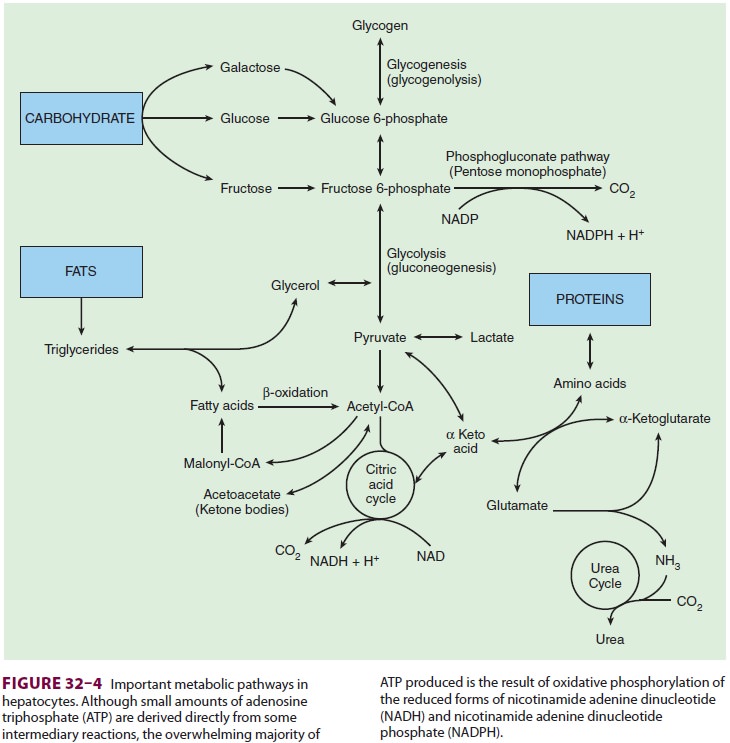

Energy is normally derived from dietary or

endogenous carbohydrates, fats, and protein. Meta-bolic breakdown of these

substrates yields the ade-nosine triphosphate required for normal cellular

function. Dietary fats and carbohydrates normally supply most of the body’s

energy requirements. Dietary proteins provide amino acids for protein

synthesis; however, when their supply exceeds requirements, amino acids also

function as energy substrates. The metabolic pathways of carbohydrate, fat, and

amino acid substrates overlap, such that some interconversions can occur

through metabolic intermediates (see Figure 32–4). Excess amino acids can

therefore be converted to carbohydrate or fatty acid precursors. Excess

carbohydrates are stored as glycogen in the liver and skeletal muscle. When

glycogen stores are saturated (200–400 g in adults), excess carbohydrate is

converted to fatty acids and stored as triglycerides, primarily in fat cells.

During starvation, the protein content of

essen-tial tissues is spared. As blood glucose concentration begins to fall

during fasting, insulin secretion decreases, and counterregulatory hormones,

such as glucagon, increase. Hepatic and, to a lesser extent, renal

glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis are enhanced. As glycogen supplies are

depleted (within 24 h), gluconeogenesis (from amino acids) becomes increasingly

important. Only neural tissue, renal medullary cells, and erythrocytes continue

to utilize glucose—in effect, sparing tissue proteins. Lipolysis is enhanced,

and fats become the principal energy source. Glycerol from the triglycerides

enters the gly-colytic pathway, and fatty acids are broken down to

acetylcoenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). Excess acetyl-CoA results in the formation of

ketone bodies (ketosis). Some fatty acids can contribute to gluconeogenesis. If

starvation is prolonged, the brain, kidneys, and muscle also begin to utilize

ketone bodies efficiently.The previously well-nourished

patient under-going elective surgery could be fasted for upto a week

postoperatively without apparent adverse effect on outcomes, provided fluid and

electro-lyte needs are met. The usefulness of nutritional repletion in the

immediate postoperative period is not well defined, but likely relates to the

degree of malnutrition, number of nutrient deficiencies, and severity of the

illness/injury. Moreover, the optimal timing and amount of nutrition support

following acute illness remain unknown. On the other hand, malnourished

patients may benefit from nutritional repletion prior to surgery.

Modern surgical practice has evolved to an expec-tation of an

accelerated recovery. Accelerated recov-ery programs generally include early

enteral feeding, even in patients undergoing surgery on the gastroin-testinal

tract, so prolonged periods of postoperative starvation are no longer common

practice. All well-nourished patients should receive nutritional support after

5 days of postsurgical starvation, and those with ongoing critical illness or

severe malnutrition should be given nutritional support immediately. The

mal-nourished patient presents a different set of issues, and such patients may

benefit from both preoperative and early postoperative feeding. Clearly, the

healing of wounds requires energy, protein, lipids, electro-lytes, trace

elements, and vitamins. Depletion of any of these substrates may delay wound

healing and pre-dispose to complications, such as infection. Nutrient depletion

may also delay optimal muscle functioning, which is important for supporting

increased respira-tory demands and early mobilization of the patient.

The resting metabolic rate can be measured

(but often inaccurately) using indirect calorimetry (known as a metabolic cart)

or by estimating energy expenditure using standard nomograms (such as the

Harris–Benedict equation), yielding an approxima-tion of daily energy

requirements. Alternatively, a simple and practical approach assumes that

patients require 25–30 kcal/kg daily. The weight is usually taken as the ideal

body weight or adjusted body weight. Even though nutritional requirements can

increase greatly above basal levels with certain condi-tions (eg, burns), the

more often relevant reason fordetermining the daily requirements is to ensure

that patients are not unnecessarily overfed. In this regard, obese patients

require adjusting the body weight based on the degree of obesity to prevent

overfeeding.

Related Topics