Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Therapeutic Management of the Suicidal Patient

Assessment of Suicidal Patients

Assessment

of Suicidal Patients

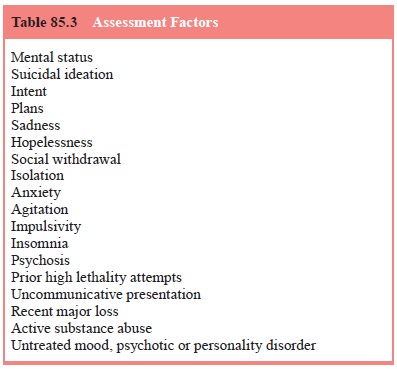

Common

presentations include acute, chronic, contingent, and/or potentially

manipulative suicidal patient. All are associated with anxiety for the care

provider doing the assessment. Careful as-sessment, use of collateral

information and acceptance of predic-tive limitations can be helpful (see Table

85.3).

As

reviewed by Nicholas and Golden (2001), factors to be considered in the

assessment of the acutely suicidal patient include the current mental status,

with special attention to direct inquiry about suicidal ideation, intent (may

be ascertained from family and friends, for example, saying good-byes or

putting af-fairs in order), and plans (well thought out with available means).

Sadness, hopelessness, social withdrawal/isolation, anxiety, agitation,

impulsivity, insomnia, psychosis (especially command hallucinations or

distressing persecutory delusions) are addi-tional concerning symptoms. These

factors, coupled with prior high lethality attempts, uncommunicative

presentation, recent major loss, active substance abuse, or untreated mood,

psychotic, or personality disorder, might indicate that hospitalization is

warranted to ensure safety prior to treating the underlying psy-chiatric

disorder (Nicholas and Golden, 2001).

Sachs and

colleagues (2001) reviewed suicide prevention strategies for bipolar

outpatients, but they can easily be adapted to any potentially suicidal

patient. The reader is reminded that “care providers can, however, be fooled by

the deceptions of a

clever

patient intent on carrying out a lethal act”. Individual-ized treatment plans

should be developed after eliciting current symptoms, including suicidal

ideation; review of risk factors, stressors, comorbid states like substance

use; and past history of suicide attempts. Acute efforts are directed toward

safety and treating the underlying disorder, with follow-up monitoring.

Ad-junctive medications like antipsychotics and anxiolytics can be beneficial.

Clinicians must monitor the amounts of medications prescribed and continue to

be vigilant during early recovery. Harm reduction strategies can include

minimizing access to le-thal means, decreasing social isolation, close

follow-up and in-forming of emergency contact procedures. Hospitalization may

be warranted if suicide is considered as a solution for problems, for active

suicidal ideation, or if there has been a recent attempt. With the caveat that

while admission may provide safety, current knowledge of risk factors do not

wholly inform when to admit or discharge, overreliance on hospitalization may

deter honest reporting, and many acutely depressed patients can be managed as

outpatients with sufficient safeguards. Involuntary admission, while not

therapy in and of itself, may be lifesaving. ECT remains a safe, typically

quick onset, effective option for those at high risk of suicide (Sachs et al., 2001).

There is

no evidence that denial of suicidal intent predicts nonsuicide. Review of

standard risk factors, additional risk factors (e.g. acute relationship and

employment changes), acute versus chronic suicidal ideation, and treatment of

readily reversible factors should be undertaken. High risk diagnoses include

major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism and substance

abuse, and borderline personality disorder. Comorbid alcoholism increases the

risk in every diagnostic category. A history of past attempts, hopelessness,

previous hospitalizations and recent discharge, while not individually

predictive, do heighten concern. Acute risk factors include severe anxiety,

panic attacks, global insomnia and agitation. These symptoms should be

carefully assessed, with aggressive intervention. Benzodiazepines and

antipsychotics can be employed to address anxiety and agitation. Caution must

be taken with benzodiazepines to avoid disinhibition and combination with

alcohol. Mixed states may require mood stabilizers. Serial assessments should

be performed with acute changes as well as chronic suicidal states.

Chronically

suicidal patients also require aggressive treatment of anxiety and agitation.

DBT and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be helpful in addressing

parasuicidal and suicidal behavior.

A significant

number of psychiatrists utilize the no-suicide contract, or the contract for

safety. Over half of a sample of psy-chiatrists acknowledged using them in

recent survey, and 41% of them had patients make suicide attempts after

entering into one (Kroll, 2000). Sixty-four percent of 14 psychiatric hospital

inpa-tient suicides denied suicidal ideation and half had some form of

no-suicide agreement in place in the week before their deaths (Busch et al., 1993). These have not been

systematically stud-ied as to whether they have any protective effect (Gray and

Otto, 2001). Resnick (2002) cautions that psychiatrists tend to view the

patient as a collaborator in treatment. However, the psychia-trist can be less

viewed as an “ally” and become an “adversary” when the patient has determined

to die by suicide. He notes that failure to recognize this shift in the

doctor–patient relationship can have devastating results. Objective evidence,

as opposed to patient subjective reports, may be telling. Alliances with family

and other caregivers should be maintained, as they can become crucial sources

of information. Resnick believes that no-suicide contracts have little

credence, especially in an adversarial rela-tionship, cause a false sense of

security for the therapist, and have no research literature to suggest efficacy

(Resnick, 2002).

Gutheil

and Schetky (1998) wrote of a most difficult as-sessment: the patient who

expresses suicidal ideation in terms of a future eventuality. The “if [event or

outcome does or does not happen], I will kill myself” contingency poses different

chal-lenges from acute suicidality, manipulative suicidal threats and chronic

suicidality. Suicidality typically engenders anxiety in the therapist.

Contingency suicidality frequently lacks verbal-ized imminence, may make

involuntary commitment difficult, and invites countertransferences which can

lead to exaggerated or inappropriately muted responses. For some patients, the

con-tingency is a defense against suicide. For others, it represents the

ultimate control. Gutheil and Schetky (1998) make several im-portant points: 1)

Some patients almost have an object relation-ship with death, with death

personified as a benevolent bringer of relief. The therapist should approach

that tie with caution, as it may be the only one in which the patient has any confidence;

2) Future deadlines should not be accepted literally; 3) Even when the

contingency is met positively, the suicidal ideation may not re-solve; 4) Some

patients view themselves as already dead, cannot conceive of life without

depression, and challenge the therapist to resurrect them. This stance

undermines any potential relation-ship; and 5) It is of benefit to negotiate a

halt to suicidal acts until depression can be separated from decision-making.

Gutheil and Schetky assert “… psychiatrists should never support suicide, but

should acknowledge the human impossibility of preventing it”. The authors note

that in these circumstances, the patient is at least communicating their

suicidal ideation. The rationale can be explored and an effort made to maintain

the therapeutic relation-ship. Helplessness should be discussed, as suicidal

ideation can be a defense against lack of control or an expression of pain. The

countertransference of the therapist should be considered, as it can cloud

clinical judgment. Consultation with colleagues can be very helpful. The

competency of the patient may be called into question, and has been used as a

defense in suicide malprac-tice cases. The clinician can frequently be

justified in involun-tary commitment as critical dates or junctures approach.

Finally, Gutheil and Schetky state that “accepting the patient’s pain and sense

of hopelessness is not the same as acceding to his or her wish to commit

suicide; the psychiatrist must always hold out hope. At the same time, it may be

therapeutic and realistic to let patients know that one can not ultimately

prevent their suicides” (Gutheil and Schetky, 1998).

Related Topics