Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Musculoskeletal Function

Assessment of Musculoskeletal Function: Physical Assessment

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

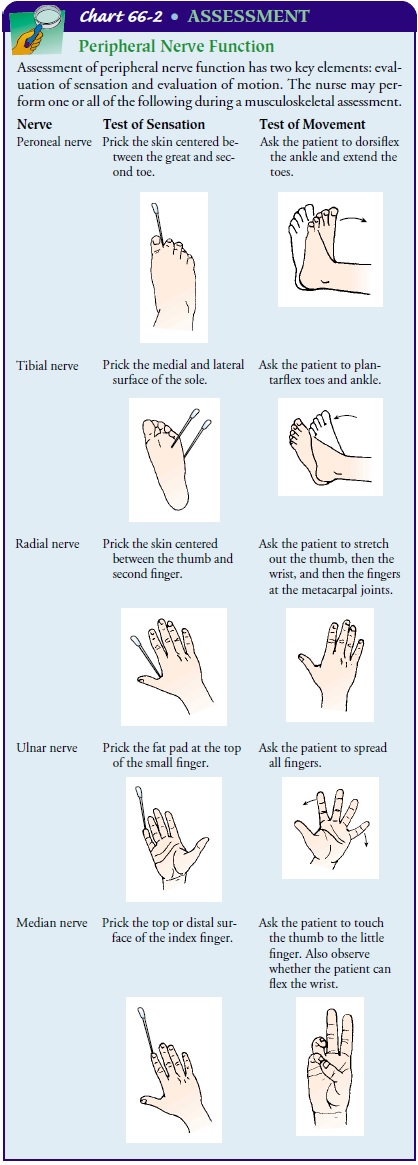

An examination of the

musculoskeletal system ranges from a basic assessment of functional

capabilities to sophisticated physical ex-amination maneuvers that facilitate

diagnosis of specific bone, muscle, and joint disorders (Chart 66-2). The

extent of assess-ment depends on the patient’s physical complaints, health

his-tory, and physical clues that warrant further exploration. The nursing

assessment is primarily a functional evaluation, focusing on the patient’s

ability to perform activities of daily living.

Techniques of inspection

and palpation are used to evaluate the patient’s posture, gait, bone integrity,

joint function, and muscle strength and size. In addition, assessing the skin

and neu-rovascular status is an important part of a complete musculo-skeletal

assessment. The nurse also should understand and be able to perform correct

assessment techniques on patients with mus-culoskeletal trauma. When specific

symptoms or physical findings of musculoskeletal dysfunction are apparent, the

nurse carefullydocuments the examination findings and shares the

information with the physician, who may decide that more extensive exami-nation

and diagnostic workup are necessary.

Posture

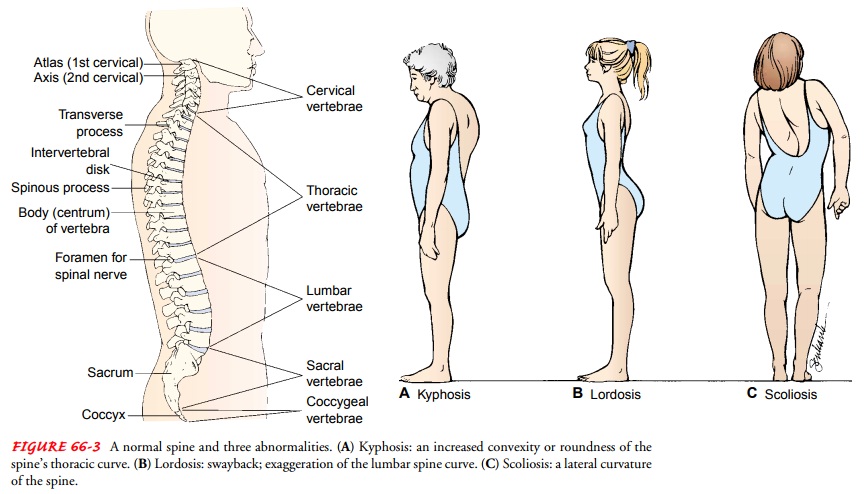

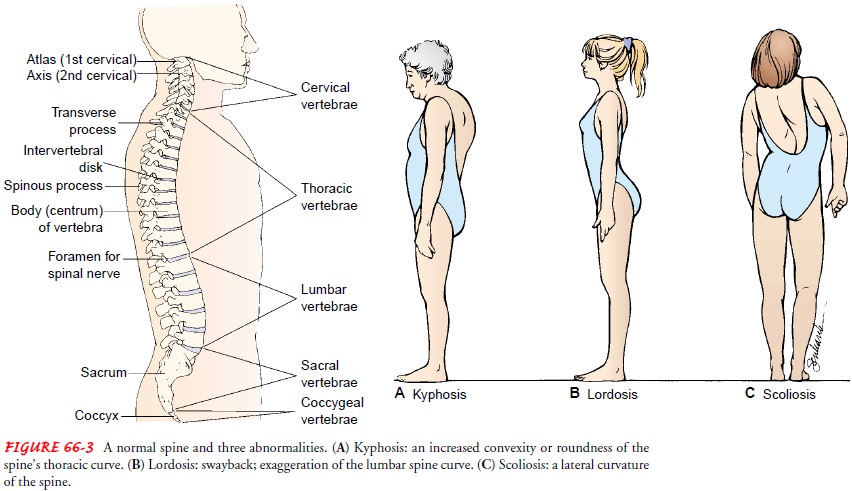

The normal curvature of

the spine is convex through the thoracic portion and concave through the

cervical and lumbar portions. Common deformities of the spine include kyphosis, an increased forward

curvature of the thoracic spine; lordosis,

or swayback, an exaggerated curvature of the lumbar spine; and scoliosis, a lat-eral curving deviation

of the spine (Fig. 66-3). Kyphosis is fre-quently seen in elderly patients with

osteoporosis and in some patients with neuromuscular diseases. Scoliosis may be

congeni-tal, idiopathic (without an identifiable cause), or the result of

damage to the paraspinal muscles, as in poliomyelitis. Lordosis is frequently

seen during pregnancy as the woman adjusts her pos-ture in response to changes

in her center of gravity.

During inspection of the spine, the entire back, buttocks, and legs are exposed. The examiner inspects the spinal curves and trunk symmetry from posterior and lateral views. Standing be-hind the patient, the examiner notes any differences in the height of the shoulders or iliac crests. The gluteal folds are normally symmetric. Shoulder and hip symmetry, as well as the line of the vertebral column, are inspected with the patient erect and with the patient bending forward (flexion).

(Scoliosis is evidenced by an abnormal lateral curve in the spine,

shoulders that are not level, an asymmetric waistline, and a prominent scapula,

accen-tuated by bending forward.) Older adults experience a loss in height due

to loss of vertebral cartilage and osteoporosis-related vertebral fractures.

Therefore, an adult’s height should be mea-sured periodically.

Gait

Gait is assessed by

having the patient walk away from the exam-iner for a short distance. The

examiner observes the patient’s gait for smoothness and rhythm. Any

unsteadiness or irregular move-ments (frequently noted in elderly patients) are

considered ab-normal. When a limping motion is noted, it is most frequently

caused by painful weight bearing. In such instances, the patient can usually

pinpoint the area of discomfort, thus guiding further examination. If one

extremity is shorter than another, a limp may also be observed as the patient’s

pelvis drops downward on the affected side with each step. Limited joint motion

may affect gait. In addition, a variety of neurologic conditions are associated

with abnormal gaits such as a spastic hemiparesis gait (stroke), steppage gait

(lower motor neuron disease), and shuffling gait (Parkinson’s disease).

Bone Integrity

The bony skeleton is

assessed for deformities and alignment. Symmetric parts of the body are

compared. Abnormal bony growths due to bone tumors may be observed. Shortened

ex-tremities, amputations, and body parts that are not in anatomic alignment

are noted. Fracture findings may include abnormal an-gulation of long bones,

motion at points other than joints, and crepitus (a grating sound) at the point

of abnormal motion. Movement of fracture fragments must be minimized to avoid

ad-ditional injury.

Joint Function

The articular system is evaluated by noting range of

motion, de-formity, stability, and nodular formation. Range of motion is

evaluated both actively (the joint is moved by the muscles sur-rounding the

joint) and passively (the joint is moved by the ex-aminer). The examiner is

familiar with the normal range of motion of major joints. Precise measurement

of range of motion can be made by a goniometer (a protractor de-signed for

evaluating joint motion). Limited range of motion may be the result of skeletal

deformity, joint pathology, or contrac-ture

of the surrounding muscles, tendons, and joint capsule. Inelderly patients,

limitations of range of motion associated with osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) may reduce their

abil-ity to perform activities of daily living.

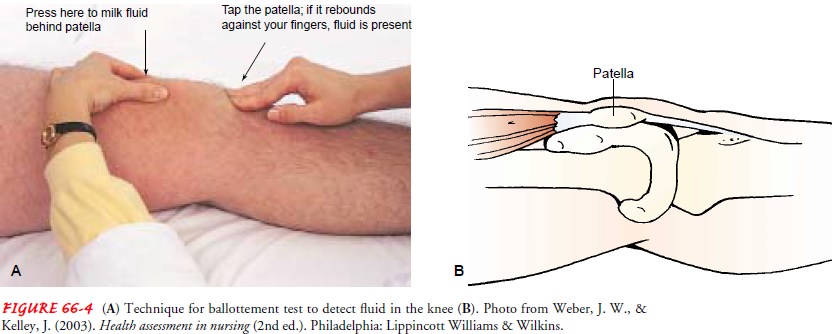

If joint motion is compromised or the joint is painful, the joint is examined for effusion (excessive fluid within the capsule), swelling, and increased temperature that may reflect active in-flammation. An effusion is suspected if the joint is swollen and the normal bony landmarks are obscured. The most common site for joint effusion is the knee. If a small amount of fluid is present in the joint spaces beneath the patella, it may be identified by the following maneuver. The medial and lateral aspects of the ex-tended knee are milked firmly in a downward motion. This dis-places any fluid downward.

As pressure is exerted against the medial or lateral side,

the examiner observes the opposite side for a bulge below the patella. When larger

amounts of fluid are pres-ent, the patella becomes elevated from the femur

during knee ex-tension and the ballottement test is positive (Fig. 66-4). If

inflammation or fluid is suspected in a joint, physician consulta-tion is

indicated.

Joint deformity may be caused by contracture (shortening of surrounding joint structures), dislocation (complete separation of joint surfaces), subluxation (partial separation of articular sur-faces), or disruption of structures surrounding the joint. Weakness or disruption of joint-supporting structures may result in a weak joint that requires an external supporting appliance (eg, brace).

Palpation of the joint

while it is passively moved provides in-formation about the integrity of the

joint. Normally, the joint moves smoothly. A snap or crack may indicate that a

ligament is slipping over a bony prominence. Slightly roughened surfaces, as in

arthritic conditions, result in crepitus

(grating, crackling sound or sensation) as the irregular joint surfaces move

across one another.

The tissues surrounding joints are examined for nodule for-mation. Rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and osteoarthritis produce characteristic nodules. The subcutaneous nodules of rheumatoid arthritis are soft and occur within and along tendons that provide extensor function to the joints. The nodules of gout are hard and lie within and immediately adjacent to the joint capsule itself.

They may rupture, exuding white uric acid crystals onto

the skin surface. Osteoarthritic nodules are hard and painless and repre-sent

bony overgrowth that has resulted from destruction of the cartilaginous surface

of bone within the joint capsule. They are frequently seen in older adults.

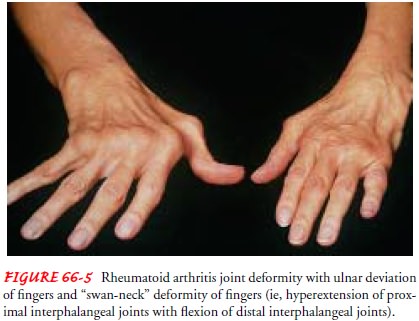

Often, the size of the joint is exaggerated by atrophy of

the muscles proximal and distal to that joint. This is seen in rheuma-toid

arthritis of the knees, in which the quadriceps muscle may atrophy

dramatically. In rheumatoid arthritis, joint involvement assumes a symmetric

pattern (Fig. 66-5).

Muscle Strength and Size

The muscular system is

assessed by noting the patient’s ability to change position, muscular strength

and coordination, and the size of individual muscles. Weakness of a group of

muscles might indicate a variety of conditions, such as polyneuropathy,

electrolyte disturbances (particularly potassium and calcium), myasthenia

gravis, poliomyelitis, and muscular dystrophy. By palpating the muscle while

passively moving the relaxed ex-tremity, the nurse can determine the muscle

tone. The nurse as-sesses muscle strength by having the patient perform certain

maneuvers with and without added resistance. For example, when the biceps are

tested, the patient is asked to extend the arm fully and then to flex it

against resistance applied by the nurse. A simple handshake may provide an

indication of grasp strength.

The nurse may elicit muscle clonus (rhythmic contractions of a muscle) in the ankle or wrist by

sudden, forceful, sustained dorsiflexion of the foot or extension of the wrist.

Fasciculations (involuntary

twitching of muscle fiber groups) may be observed.

The nurse measures the girth of an extremity to monitor in-creased size due to exercise, edema, or bleeding into the muscle. Girth may decrease due to muscle atrophy. The unaffected ex-tremity is measured and used as the reference standard. Measure-ments are taken at the maximum circumference of the extremity. It is important that the measurements be taken at the same loca-tion on the extremity, and with the extremity in the same position, with the muscle at rest. Distance from a specific anatomic land-mark (eg, 10 cm below the medial aspect of the knee for mea-surement of the calf muscle) should be indicated in the patient’s record so that subsequent measurements can be made at the same point. For ease of serial assessment, the nurse may indicate the point of measurement by marking the skin. Variations in size greater than 1 cm are considered significant.

Skin

In addition to assessing

the musculoskeletal system, the nurse in-spects the skin for edema,

temperature, and color. Palpation of the skin can reveal whether any areas are

warmer, suggesting increased perfusion or infection, or cooler, suggesting

decreased perfusion, and whether edema is present. Cuts, bruises, skin color,

and evi-dence of decreased circulation or infection can influence nursing

management of musculoskeletal conditions.

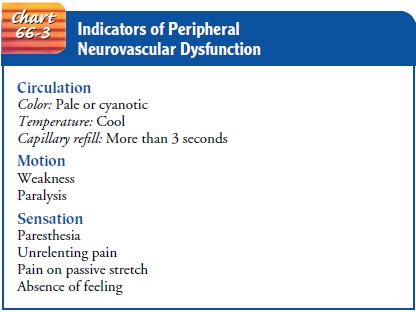

Neurovascular Status

It is important for the

nurse to perform frequent neurovascular assessments of patients with

musculoskeletal disorders (especially of those with fractures) because of the

risk of tissue and nerve dam-age. One complication that the nurse needs to be

alert for when assessing the patient is compartment syndrome, which is

described in detail later in this unit. This major neurovascular problem is

caused by pressure within a muscle compartment that increases to such an extent

that microcirculation diminishes, leading to nerve and muscle anoxia and

necrosis. Function can be permanently lost if the anoxic situation continues

for longer than 6 hours. Assessment of neurovascular status (Chart 66-3) is

frequently re-ferred to as assessment of CMS (circulation, motion, and

sensation).

The Patient With Musculoskeletal Injury

Special precautions must be taken when assessing a trauma pa-tient. If there is injury to an extremity, it is important to assess for soft tissue trauma, deformity, and neurovascular status. If the pa-tient has a possible cervical spine injury and is wearing a cervical collar, the collar must not be removed until the absence of spinal cord injury is confirmed on x-ray. When the collar is removed, the cervical spine area is gently assessed for swelling, tenderness, and deformity. With pelvic trauma, abdominal organ injuries may occur. The patient is assessed for abdominal pain, tender-ness, hematomas, and the presence or absence of femoral pulses. If blood is present at the urinary meatus, the nurse should sus-pect bladder and urethral injury, and the patient should not be catheterized. Instead, such findings should be reported imme-diately to the primary health care provider.

Related Topics