Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Substance Abuse: Cannabis-related Disorders

Assessment and Differential Diagnosis - Cannabis-related Disorders

Assessment and Differential

Diagnosis

Cannabis-related Disorders

To diagnose any of the cannabis-related disorders,

it is impor-tant to obtain a detailed history of the individual’s pattern of

substance abuse (including abuse not only of cannabis but of other substances)

and to attempt to substantiate this report with toxicology screening for drugs

of abuse. Individuals who smoke cannabis regularly can have substantial

accumulations of THC in their fat stores. Thus, for weeks after cessation of

smoking, de- tectable levels of cannabinoids may be found in urine (Johnson,

1990). However, a positive response on toxicology screening for cannabinoids

cannot establish any of the cannabis-related diag-noses; it is useful only as

an indicator that these diagnoses should be considered.

Cannabis Dependence

It is uncommon to see patients who exhibit cannabis

depend-ence as their only diagnosis because such individuals rarely seek

treatment as they generally do not acknowledge that they have a problem and are

unaware that treatment is available. However, some patients with this disorder

will respond to offers for treat-ment because they realize that they are unable

to stop use on their own and because they notice the deleterious effect of

compulsive use (Roffman and Barnhart, 1987). Therefore, the diagnosis of

cannabis dependence will most often be made in patients who present with other

psychiatric problems, such as mood and anxi-ety disorders, and other substance

use disorders. Another manner in which individuals with cannabis dependence may

come to the attention of psychiatrists is when they are arrested for possession

of the substance or some crime related to cannabis abuse, such as driving under

the influence of the drug. Nevertheless, cannabis dependence is probably

underdiagnosed in both psychiatric and general medical populations because it

is not considered.

The diagnosis of cannabis dependence cannot be made

without obtaining a history indicating that the cannabis use is impairing the

patient’s ability to function either physically or psychologically. Areas to

inquire about include the patient’s per-formance at work, ability to carry out

social and family obliga-tions, and physical health. It is also important to

find out how much of the patient’s time is spent on cannabis-related activities

and whether the patient has tried unsuccessfully to stop or cut down on use in

the past. Although it has been our experience that people who have used

cannabis daily over a period of years almost invariably report tolerance to

many of the effects of can-nabis and to experience an unpleasant withdrawal

state if use is discontinued, neither tolerance nor withdrawal is necessary for

the diagnosis of cannabis dependence. When this diagnosis is made, it can be

described further by the following specifiers: with or without physiological

dependence, early full or partial remission, sustained full or partial

remission, or in a controlled environment. These diagnostic distinctions must

be based on the pattern of use reported by the patient.

Cannabis Abuse

Most individuals who are diagnosed with cannabis

abuse have only recently started using cannabis. As with cannabis depend-ence,

cannabis abuse is unlikely to be diagnosed unless some additional condition or

circumstance brings the individual to medical attention. Teenagers often fall

into this category because they spend time in supervised environments like

school and home where responsible adults may intervene. Also, teenagers are

more likely to have motor vehicle accidents while intoxicated because they are

inexperienced drivers, and are more likely to be arrested for possession

because they have a greater tendency to participate in risky behaviors of all

types.

Although virtually all individuals with cannabis

depend-ence meet the inclusion criteria for cannabis abuse, they cannot be

given this diagnosis because the presence of cannabis depend-ence is an

exclusion criterion. Undoubtedly, the vast majority of people with cannabis

dependence would have been given the diagnosis of cannabis abuse until they

developed dependence.

It is probable that individuals qualifying for a

diagnosis of can-nabis abuse will either cease use or develop cannabis

dependence. The criteria for cannabis abuse focus on adverse consequences of

cannabis use that could potentially re-sult from just a single use such as

failure to fulfill obligations at work, school, or home, participating in

potentially dangerous activities like driving while intoxicated with cannabis,

having cannabis-related legal problems, or social or interpersonal

dif-ficulties. Even though these adverse consequences can occur following a

single episode of cannabis use, the consequences must be recurrent, requiring

multiple episodes of use. Since the number of episodes necessary for

“recurrent” is not defined, and the pattern of use is often dependent on

patient self-report, it is often difficult to distinguish between abuse and

dependence. This difficulty is easier to recognize if one looks at the

extremes. On one end of the continuum, a high school student who actually has

only used cannabis twice, but who was unfortunate enough to be caught and

suspended from school on both occasions, would appropriately be diagnosed with

cannabis abuse. At the other end of the continuum, a high school student who

had actually been using cannabis every day for three years and met the criteria

for dependence, who was also caught and suspended from school twice but denied

symptoms of dependence, would incorrectly be diagnosed with cannabis abuse.

The difference between people with cannabis abuse

and those with cannabis dependence is that the people with depend-ence have

been using more regularly (one or more times per day) and for a longer duration

(one or more years), and the acute prob-lems associated with abuse have turned

into the chronic problems associated with dependence. For example, what started

as failure to fulfill obligations at work or school has resulted in dropping

out of school or working at jobs with extremely low expectations. Multiple car

accidents or arrests have led to chronic injuries (of-ten associated with

obtaining SSDI), loss of licenses, probation and even periods of time in

prison. Social or interpersonal prob-lems have resulted in isolation or at

least separation from people who are not regular cannabis users. If there is a

committed rela-tionship where the partner is typically cannabis dependent, and

if children are involved, chronic neglect is present if caring for children

while intoxicated with cannabis represents neglect.

Cannabis Intoxication

There are four criteria necessary to make this

diagnosis (see DSM-IV criteria for intoxication). The first is that recent use

of cannabis must be established. This cannot be done with toxicol-ogy screening

because the result may be negative after a single episode of smoking or,

alternatively, may be positive even if the individual has not used the drug for

a time much longer than the period of intoxication (see section on Cannabis

botany and phar-macology). Thus, the recent use of cannabis must be reported by

the patient or another person who witnessed the patient’s use. In addition, the

symptoms resulting from cannabis use must pro-duce “clinically significant

maladaptive behavioral or psycho-logical changes”. Thirdly, the patient must

exhibit some physical signs of cannabis use. DSM-IV-TR requires the patient to

have at least two of four signs – conjunctival injection, increased ap-petite,

dry mouth and tachycardia – within 2 hours of cannabis use. Fourthly, symptoms

cannot be accounted for by a general medical condition or another mental

disorder. There is a specifier, “with perceptual disturbances”, that can be

used if the patient is experiencing illusions or hallucinations while not

delirious and while maintaining intact reality testing.

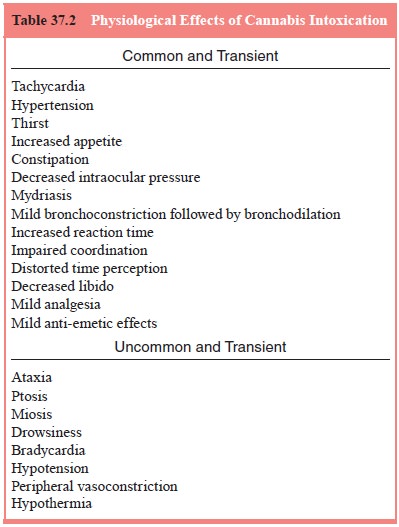

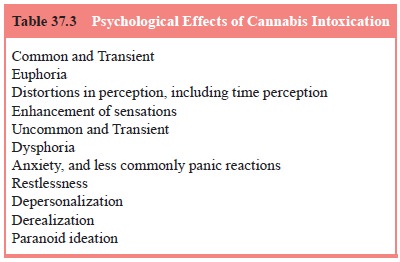

There has been extensive research on the effects of

acute cannabis intoxication. In addition to the symptoms and signs required for

a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis, many psychological and physiological effects have been

reported. Awareness of these may enhance the psychiatrist’s ability to

recognize cannabis intoxica-tion. Physiological effects are listed in Table

37.2, and are divided into commonly observed effects and rare effects that have

been described only after the use of very high doses of cannabis (Hall and

Solowij, 1998; Ameri, 1999; Perez-Reyes, 1999). Cannabis has low toxicity, and

to our knowledge, no deaths from canna-bis overdose have been reported (Hall

and Solowij, 1998). Simi-larly, psychological effects are listed in Table 37.3,

divided into commonly observed effects and uncommon effects. Most people find

the commonly experienced psychological effects enjoyable. However, some

individuals, especially women (Thomas, 1996)

and inexperienced users in an unfamiliar

environment, find them frightening and experience anxiety and even have panic

reactions (Hall and Solowij, 1998; Johns, 2001; Thomas, 1996). Although all of

these effects typically persist only for the period of acute intoxication, some

reports have described individuals who report “flashbacks” of cannabis

intoxication long after use, and deper-sonalization persisting long after acute

intoxication (Keeler et al., 1968,

1971; Levi and Miller, 1990; Annis and Smart, 1973; Stanton and Bardoni, 1972).

At this time there is insufficient evidence to ascertain whether these reports

are attributable to cannabis itself, to confounding factors such as the

concomitant use of other drugs, or the presence of other Axis I disorders

(Johns, 2001).

In addition, cannabis use produces deficits in a

number of neuropsychological functions, both during acute intoxication and after

up to a week or more of abstinence in chronic, long-term users. These tasks

include short-term memory, sustained or divided attention, and complex

decision-making (Ehrenreich et al.,

1999; Pope et al., 1995, 1997, 2001a;

Pope and Yurgelun-Todd, 1996; Schwartz et

al., 1989; Solowij et al., 1991,

1995; Solowij, 1995, 1998). A study of chronic, long-term users found that

these deficits were reversible after 28 days of abstinence (Pope et al., 2001a). However, a few studies

have found that sub-tle electrophysiologic changes, of uncertain clinical

significance, may persist even after years of abstinence (Solowij, 1995, 1998;

Struve et al., 1998).

Cannabis Intoxication Delirium

We have not located any original reports of this

entity, although it is mentioned in various reviews and is included in DSM-IV.

Thus, if cannabis intoxication delirium does occur in neurologi-cally intact

individuals, it is probably a rare complication. If the delirium does not

resolve within 24 to 48 hours, it is almost cer-tainly a result of an

underlying neurological or medical condi-tion. Therefore, in a patient with

delirium, even if recent cannabis use has been reported, a full diagnostic

work-up should be per-formed to rule out a concomitant, treatable neurological

condi-tion (Halikas, 1974; Johns, 2001).

The following two substance-induced conditions are

not generally diagnosed unless the symptoms are in excess of those usually

associated with the intoxication or withdrawal state and are sufficiently

severe to warrant independent clinical attention.

Cannabis-induced Psychotic Disorder

There are two subtypes of cannabis-induced

psychotic disor-der: one featuring delusions, the other hallucinations. The

di-agnosis of this disorder is readily made in individuals who have psychotic

symptoms that appear immediately after ingestion of cannabis. However, a

careful history is required to establish whether the individual has a

preexisting psychotic disorder (as is often the case in such situations) or

whether the symptoms arose de novo after

cannabis consumption. There is little evi-dence that cannabis-induced psychotic

disorders can arise in previously asymptomatic individuals (Gruber and Pope,

1994). Therefore, if psychotic symptoms persist for 24 to 48 hours af-ter the

period of acute intoxication, they are likely due to an underlying psychiatric

disorder which must be diagnosed and treated (Hall and Degenhardt, 2000; Johns,

2001, Gruber and Pope, 1994).

Cannabis-induced Anxiety Disorder

This disorder may be further described by the following

specifiers: with generalized anxiety, with panic attacks, with

obsessive–compulsive

symptoms and with phobic symptoms. The literature contains papers that report

individuals who have anxiety, panic reactions and paranoid ideation during the

period of acute intoxication, but we are unaware of any papers that re-port obsessive–compulsive

or phobic symptoms. People who ex-perience anxiety after using cannabis are

typically inexperienced users who react to the novel experiences of perceptual

distortions and intensified sensations with anxiety and even panic reactions,

rather than enjoyment (Thomas, 1996; Johns, 2001; Szuster et al., 1988). Women are more likely than men to experience

canna-bis-induced anxiety (Thomas, 1996). As with cannabis-induced psychotic

disorders, we have been unable to find clear cases of cannabis-induced anxiety

disorders in individuals without a preexisting Axis I disorder. Again, if

symptoms of severe anxiety or panic persist for 24 to 48 hours after the period

of acute intoxi-cation, they are likely due to an underlying psychiatric

disorder that must be diagnosed and treated (Johns, 2001).

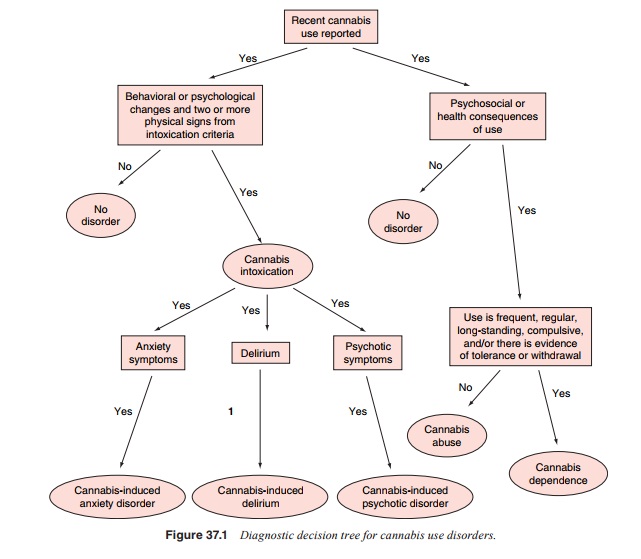

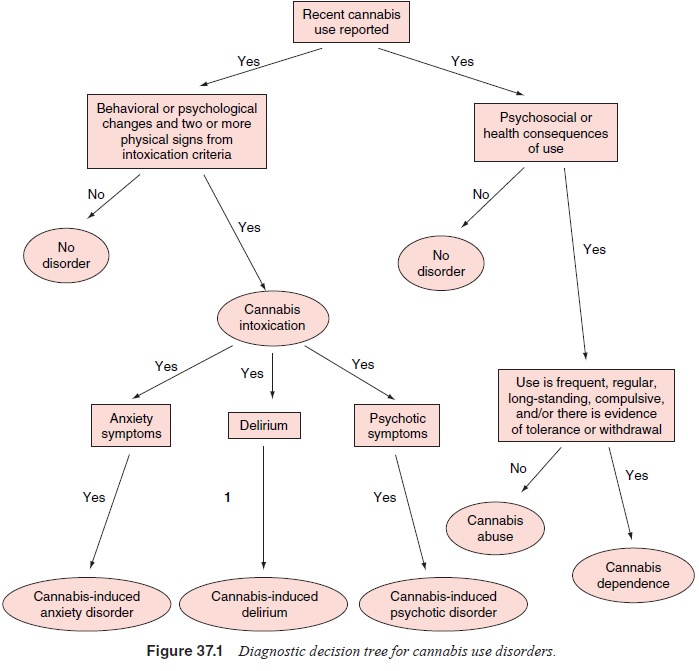

A

diagnostic decision tree for cannabis use disorders is presented in Figure

37.1.

Related Topics