Chapter: Mechanical : Finite Element Analysis : Applications in Heat Transfer & Fluid Mechanics

Applications in Heat Transfer & Fluid Mechanics

APPLICATIONS IN HEAT TRANSFER &FLUID MECHANICS

ONE DIMENSIONAL HEAT TRANSFER ELEMENT

In structural problem

displacement at each nodel point is obtained. By using these displacement

solutions, stresses and strains are calculated for each element. In structural

problems, the unknowns are represented by the components of vector field. For

example, in a two dimensional plate, the unknown quantity is the vector field

u(x,y),where u is a (2x1)displacement vector.

Heat transfer can be defined as

the transmission of energy from one region another region due to temperature

difference. A knowledge of the temperature distribution within a body is important

in many engineering problems. There are three modes of heat transfer.

They are: (i) Conduction

(ii) Convection

(iii)Radiation

1Strong Form for Heat Conduction in One Dimension

with Arbitrary Boundary Conditions

Following

the same procedure as in Section, the portion of the boundary where the

temperature is prescribed, i.e. the essential boundary is denoted by T and the boundary where the flux is

prescribed is recommended for Science and

Engineering Track. Denoted by q ; these

are the boundaries with

natural boundary conditions. These boundaries

are complementary, so

With the unit normal used in , we can express

the natural boundary condition as qn ¼ q. For example, positive flux q

causes heat inflow (negative q ) on the left boundary point where

qn ¼ q ¼ q and heat outflow (positive q ) on the right boundary point where qn

¼ q ¼ q.

![]()

Strong

form for 1D heat conduction problems

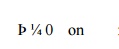

2Weak Form for Heat Conduction in

One Dimension with Arbitrary Boundary Conditions

We again multiply the first two

equations in the strong form by the weight function and integrate over the

domains over which they hold, the domain for the differential equation and the

domain q for the flux boundary condition, which

yields ws

dx with w ¼

T and

combining with gives

Recalling that w ¼ 0 on

Weak form

for 1D heat conduction problems

Find T

ðxÞ 2 U such that

Notice the similarity between

APPLICATION TO HEAT TRANSFER TWO-DIMENTIONAL

1Strong

Form for Two-Point Boundary Value

Problems

The equations developed in this

chapter for heat conduction, diffusion and elasticity problems are all of the

following form:

Such

one-dimensional problems are called two-point boundary value problems. gives

the particular meanings of the above variables and parameters for several

applications. The natural boundary conditions can also be generalized as (based

on Becker et al. (1981))

Equation

is a natural boundary condition because the derivative of the solution appears

in it. reduces to the standard natural boundary conditions considered in the

previous sections when bðx Þ ¼ 0. Notice that the essential boundary condition

can be recovered as a limiting case of when bðxÞ is a penalty parameter, i.e. a

large number In this case, and Equation is

called a generalized boundary condition.

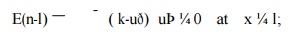

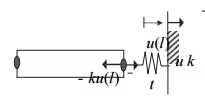

An

example of the above generalized boundary condition is an elastic bar with a spring attached as shown in In this case,

bðlÞ ¼ k and reduces to

where ¼ k is the spring

constant. If the spring stiffness is set to a very large value, the above

boundary condition enforces ¼ u; if we let k ¼ 0, the above boundary condition

corresponds to a prescribed traction boundary. In practice, such generalized

boundary conditions are often used to model the influence of the surroundings.

For example, if the bar is a simplified model of a building and its foundation,

the spring can represent the stiffness of the soil.

2 Two-Point Boundary Value Problem With Generalized

Boundary Conditions

An

example of the generalized boundary for elasticity problem.

Another example of the application of this boundary condition

is convective heat transfer, where energy is transferred between the

surface of the wall and the surrounding medium. Suppose convective heat

transfer occurs at x ¼ l. Let T ðlÞ be the wall temperature at x ¼ l and T be the temperature in the medium. Then the flux at the boundary x

¼ l is given by qð lÞ ¼ hðT ðlÞ T Þ, so bðlÞ ¼

h and the boundary condition is

where h is convection coefficient, which has dimensions of W m 2 o C 1 . Note that when the convection

coefficient is very large, the temperature T is immediately felt at x ¼ l and

thus the essential boundary condition is again enforced as a limiting case of

the natural boundary condition.

There are two approaches to deal with the boundary

condition . We will call them the penalty and partition methods. In the penalty

method, the essential boundary condition is enforced as a limiting case of the

natural boundary condition by equating bðxÞ to a penalty parameter. The

resulting strong form for the penalty method is given in.

General

strong form for 1D problems-penalty method

þ f

¼ 0

on ;

In the partition approach, the total boundary is

partitioned into the natural boundary, and the complementary essential

boundary, The natural boundary condition has the generalized form defined by

The resulting strong form for the partition method is summarized in.

3

Weak Form

for Two-Point Boundary Value Problems

In this section, we will derive the general weak

form for two-point boundary value problems. Both the penalty and partition

methods described in will be considered. To obtain the general weak form for

the penalty method, we multiply the two equations in the strong by the weight

function and integrate over the domains over which they hold: the domain for

the differential equation and the domain for the generalized boundary

condition.

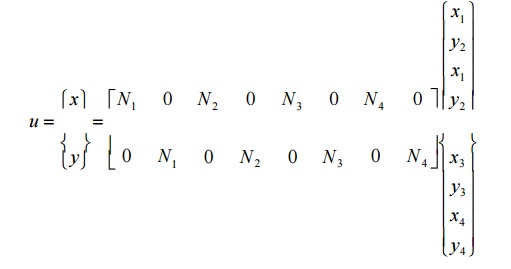

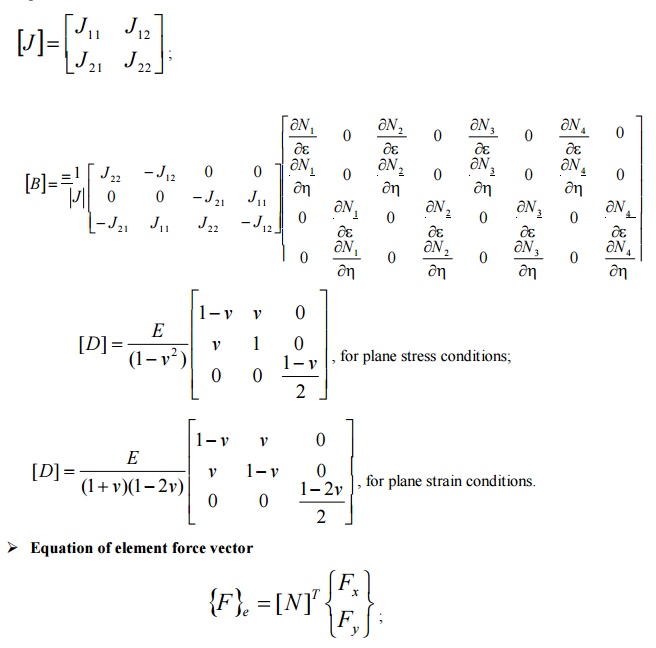

SCALE VARIABLE PROBLEM IN 2 DIMENSIONS

Ø Equation of Stiffness Matrix for 4 noded

isoparametric quadrilateral element

N –Shape function,

Fx –load or force along x direction,

Fy –load or

force along y direction.

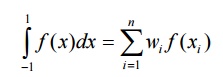

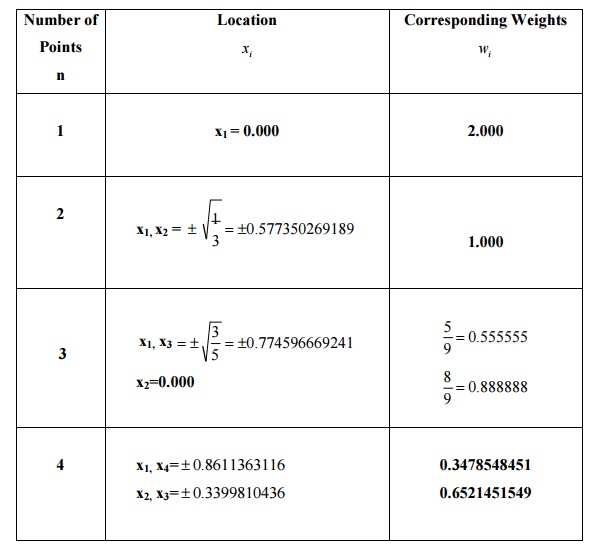

Ø Numerical

Integration (Gaussian Quadrature)

The Gauss

quadrature is one of the numerical integration methods to calculate the

definite integrals. In FEA, this Gauss quadrature method is mostly preferred.

In this method the numerical integration is achieved by the following

expression,

Table

gives gauss points for integration from -1 to 1.

Ø Problem (I set)

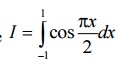

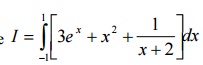

1. Evaluate  by applying 3 point Gaussian quadrature and compare with exact

solution.

by applying 3 point Gaussian quadrature and compare with exact

solution.

2. 2. Evaluate  using one point and two point Gaussian quadrature. Compare

with exact solution.

using one point and two point Gaussian quadrature. Compare

with exact solution.

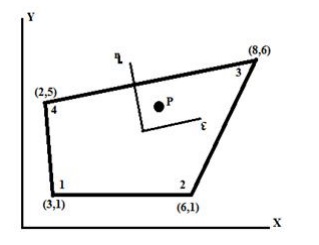

3. 3. For

the isoparametric quadrilateral element shown in figure, determine the local co

–ordinates

of the point P which has Cartesian co-ordinates (7, 4).

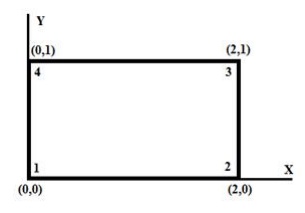

4. A four noded rectangular element is in

figure. Determine (i) Jacobian

matrix, (ii) Strain

–

Displacement matrix and

(iii) Element Stresses.

Take

E=2x105N/mm2,υ= 0.25,u=[0,0,0.003,0.004,0.006,.004,0,0]T,

Ɛ= 0, ɳ=0.

Assume

plane stress condition.

2 DIMENTIONAL FLUID MECHANICS

The

problem of linear elastostatics described in detail in can be extended to

include the effects of inertia. The resulting equations of motion take the form

where

u = u(x1 , x2, x3 , t) is the unknown displacement field, ρ is the mass

density, and I = (0, T ) with T being a given ti me. Also, u0 and v0 are the prescribed initi al

displacement and velocity fields.

Clearly, two sets

of boundary conditions are

set on Γu

and Γq , respectively, and are assumed to hold

throughout the time interval I . Likew ise, two sets of initial conditions are

set for the whole domain Ω at time t = 0. The stron g form of the resulting initial/boundary- value problem is

stated as follows: given functions f , t, u¯ , u0 and v0, as well as a

constitutive equation for σ, find u in Ω × I , such that the equations are

satisfied.

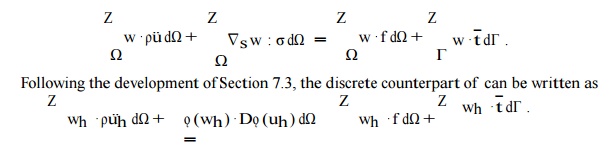

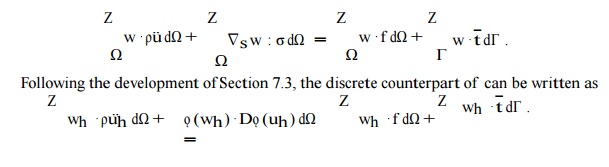

A

Galerkin-based weak form of the linear elastostatics problem has been derived

in Sec-tion In the elastodynamics case, the only substantial difference

involves the inclusion of the term RΩ w • ρu¨ dΩ, as long as one adopts the

semi-discrete approach. As a result, the

weak form at a fixed time can be expressed as

Following a standard proced ure, the contribution of the

forcing vector Fi nt,e due to interele- ment tractions is neglected

upon assembly of the global equations . As a result, the equations is give rise

to their assembled counterparts in the form

Mu + Kuˆ = F ,

where uˆ is the global unknown

displacement vector1 . The preceding equat ions are, of course,

subject to initial conditions t hat can be written in vectorial form as uˆ(0) = uˆ0 and vˆ(0) = vˆ0

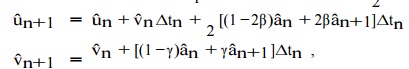

The most commonly emp loyed method for the

numerical solution of t he system of

coupled linear second-order ordi nary differential equations is the Newmark m

ethod. This

method is based

on a time series expansion of ˆu

and ˆ u˙ := v.ˆ Concentrating on the time interval (tn

,tn+1], the New mark method is defined by the equations

It is

clear that the Newmark equations define

a whole family of time inte grators.

It is important to distinguish this family into two

categories, namely implicit and explicit integrators, corresponding to β > 0

and β = 0,

respectively.

The overhead “hat” symbol

is used to distinguish between the vector field u and the solution vector uˆemanating

fr om the finite element approximation of the vector field u.

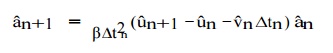

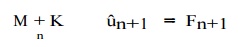

The general implicit Newmar k

integration method may be implemented as follows: first, solve (9.18)1

for aˆn+1 , namely

write

Then, substitute (9.19)

into the semi-discrete form (9.17) evaluated at tn+1 to find that

After solving for uˆn+1, one ma

y compute the acceleration aˆn+1 from and

the velocity vˆn+1 from.

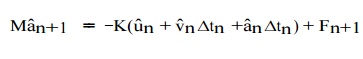

Finally, the general explicit N ewmark integration method may

be implemented as follows: starting from the semi-discrete e quations evaluated

at tn+1, one may substitute uˆn+1from to

find that

If M is

rendered diagonal (see discussion in our pages ), then aˆn+1 can be

determined without solving any

coupled linear algebraic

equations. Then, ˆ are the

velocities bvn+1 immediately computed

from (9. 18)2. Also, the

displacements uˆ n+1 are computed from indepen-dently of the acceleratio ns

aˆn+1 .

Related Topics