Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Antidepressants

Antidepressants: The Formulation of Treatment

The

Formulation of Treatment

Indications

All

antidepressants are indicated for the treatment of acute ma-jor depressive

episodes. Beyond the acute period, there is also evidence for the use of

antidepressants in the prevention of re-lapse and recurrence.

There are

a number of more minor forms of depression, many of which may also respond to

antidepressant medication. Best studied of these is dysthymic disorder.

Previously thought to be unresponsive to somatic therapy, a growing literature

at-tests to the responsiveness of this chronic, minor depressive disorder to a

variety of medications, including TCAs (Kocsis et al., 1985; Stewart et al.,

1993) and serotonin reuptake inhibi-tors (Hellerstein et al., 1993; Thase et al.,

1996; Ravindran et al., 1994;

Vanelle, 1997). As with major depression, there is no de-finitive data to

suggest that any one agent is more efficacious than the other. The bulk of data

suggests, instead, that any available agent used for major depression is likely

to be effective for these other disorders.

Other

minor depressive disorders include minor depres-sion and recurrent brief

depression. Though rigorous data is largely lacking in the treatment of these

disorders, they seem to show an at least modest response to antidepressant

medications.

Other Uses for Antidepressants

Although

we will describe the use of anti-depressants in the treatment of major

depression, they are also used to treat a number of other conditions (Orsulak

and Waller, 1989; Brotman, 1993). Some uses have gained general accept-ance

while other uses rely on moderate or preliminary evidence. A summary of various

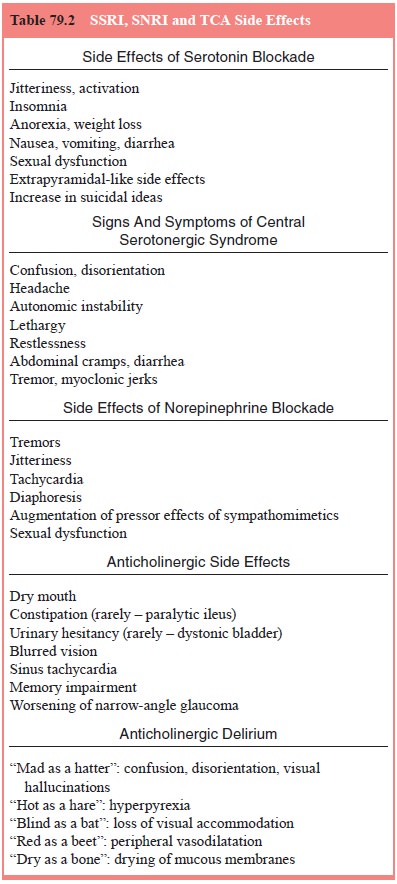

indications is presented in Table 79.2.

Selection of an Antidepressant

The

decision whether to treat depressive symptoms with phar-macotherapy requires an

assessment of both the need for in-tervention and the likelihood that treatment

will be successful. Assessing the need for intervention involves longitudinal

and cross-sectional factors. Assessing the likelihood that treatment will be

successful is somewhat more difficult, but may rely on clinical, demographical

and biological factors.

Assessing the Need for Intervention

This

involves assessing the likely result if pharmacological treat-ment is not

given. It is essential in making a useful risk–benefit assessment.

Longitudinal Factors The

physician should consider the course and

duration of previous episodes of depression. Such episodes can predict the

potential severity of the current episode, the likely time to recovery, and the

probability of a subsequent recurrence. The physician should also consider the

likely complications of depression for the individual patient, which may

include sub-stance abuse and suicide.

Cross-sectional Factors The

physician should consider the severity

of symptoms and the degree of functional impairment. Suicidal ideation is of

particular concern and needs rapid and in-tensive treatment. Such treatment

often includes hospitalization. Even with less pressing symptoms, but

significant occupational or social impairment, the risk–benefit ratio generally

still favors a trial of antidepressants, particularly now that safer and more

easily tolerated agents are available.

Selection of a Particular Agent Although,

as noted earlier, the various

antidepressants seem to have equal efficacy in the treat-ment of depression, a

given patient may respond preferentially to one, or a class of agents. Again,

cross-sectional and longitudinal factors should be taken into account.

Pharmacokinetic Concerns

First-generation Antidepressants The

pharmacokinetics of TCAs is complex.

This complexity is reflected in the diversity of half-lives reported, which

vary roughly from 10 to 40 hours. TCAs are primarily absorbed in the small

intestine. They are usually well absorbed, and reach peak plasma levels 2 to 6

hours

after

oral administration. Absorption can be affected by changes in gut motility. The

drugs are extensively metabolized in the liver on first pass through the portal

system. They are lipophilic, have a large volume of distribution and are highly

protein-bound (85–95%). TCAs are metabolized in the liver by hepatic

micro-somal enzymes, by demethylation, oxidation, or hydroxylation. They are

generally metabolized to active metabolites, and are excreted by the kidneys.

There is a large range of elimination half-lives among the antidepressants.

MAOIs are

also well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Their metabolism, although

quite efficient (they have a half-life of 1 to 2 hours), is not well

understood. The short half-life of these compounds is not entirely relevant

however, as they bind irreversibly with MAO. Thus, the activity of these drugs

depends less on pharmacokinetics, and more on the synthesis of new MAO to

restore normal enzyme activity. This synthesis re-quires approximately 2 weeks.

Second-generation Antidepressants All of

the available serot-onin reuptake inhibitors are well absorbed, and not

generally af-fected by food administration. Sertraline is an exception to this

rule, and its blood level may be increased by food. All serotonin reuptake

inhibitors have large volumes of distribution and they are extensively

protein-bound. They are metabolized by hepatic microsomal enzymes and are

potent inhibitors of these enzymes (a fact which will be discussed later in

greater detail).

The only

serotonin reuptake inhibitor with an active me-tabolite is fluoxetine, whose

metabolite norfluoxetine has a half-life of 7 to 15 days. Thus, it may take

several months to achieve steady state with fluoxetine. This is considerably

longer than cita-lopram, which has a half-life of about 1.5 days, or sertraline

and paroxetine, which have half-lives of about a day.

As

previously discussed, there is no correlation between half-life and time to

onset. Drugs with shorter half-lives have an advantage in cases where rapid

elimination is desired (for exam-ple, in the case of an allergic reaction).

Drugs with a longer half-life may also have advantages: fluoxetine, for

example, has been successfully given in a once-weekly dosing during the

continu-ation phase of treatment (Burke et

al., 2000), and a once-weekly formulation of this drug is currently

available. All serotonin reuptake inhibitors are eliminated in the urine as

inactive me-tabolites. Both fluoxetine and paroxetine are capable of inhibiting

their own clearance at clinically relevant doses. As such, they have nonlinear

pharmacokinetics: changes in dose can produce proportionately large plasma

levels.

As with

most of the other antidepressants, bupropion un-dergoes extensive first pass

metabolism in the liver. Although the parent compound has a half-life of 10 to

12 hours, it has three me-tabolites that appear to be active. One, threohydrobupropion,

has a half-life of 35 hours and is relatively free in plasma (it is only 50%

protein-bound). There is considerable individual variability in the levels of

bupropion and its metabolites. Trazodone has a half-life that is relatively

short, having a range of 3 to 9 hours. Given this, and its apparent lack of

active metabolites, the plasma levels of trazodone can be quite variable during

a day. For this reason, the medication requires divided dosing.

Third-generation Antidepressants Venlafaxine

has a short half-life (4 hours);

however, it is available in an extended release formulation that allows

once-daily dosing. It appears to have a dual effect, in which at lower doses it

primarily acts on the serotonin transporter, and clinically significant

norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is not seen until higher doses are used (150

mg/day and above).

Nefazodone

has relatively low bioavailability, and a short half-life (2–8 hours), and thus

it is usually given in twice-daily doses. Mirtazapine has a half-life of 13 to

34 hours.

Related Topics