Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Preconception and Antepartum Care

Antepartum Patient Education

ANTEPARTUM PATIENT EDUCATION

Plans for the antepartum,

intrapartum, and postpartum periods provide an opportunity for patient

education and interaction. The Antepartum Record in Appendix C provides a list

of the issues to be discussed during ante-partum care.

Employment

A woman with an uncomplicated

pregnancy can usually continue to work until the onset of labor. In a normal

pregnancy, there are few restrictions concerning work, although it is

beneficial to allow moderate activity and to allow for periods of rest. Strenuous

work (standing or repetitive, strenuous, physical lifting) is best avoided.

A period of 4 to 6 weeks

generally is required for a woman’s physical condition to return to normal.

However, the patient’s individual circumstances may be a factor in determining

when she returns to work. The length of a woman’s leave from work can depend on

whether there are pregnancy or delivery complications, the work involved, the

employer attitude, the rules of the health care system under which the patient

receives care, and the wishes of the patient. The Federal Family and Medical

Leave Act and state laws should be consulted to determine the family and

medical leave that is available.1(p118)

Exercise

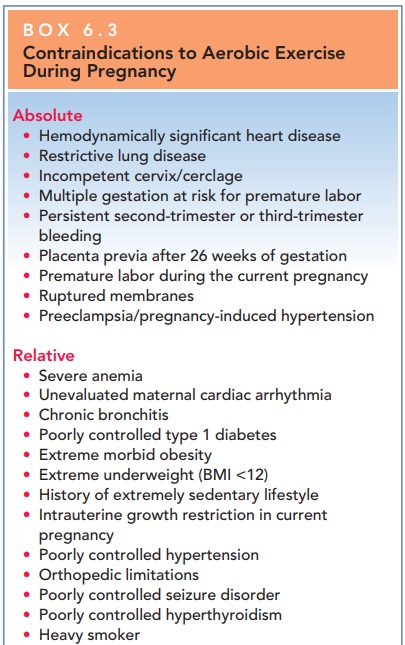

In the absence of either medical

or obstetric complications, up to 30 minutes of moderate exercise per day on

most if not all days of the week is acceptable (Box 6.3). Each sport should be

reviewed for its potential risk, and activities with a high risk for falling or

for abdominal trauma should be avoided.

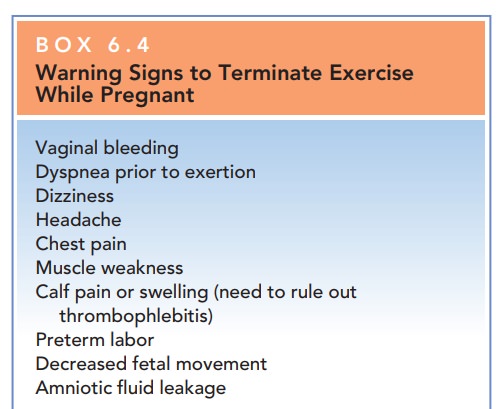

Overly strenuous exercise,

especially for prolonged periods, should be avoided. Patients unaccustomed to

reg-ular exercise should not undertake vigorous new programs during pregnancy. Supine exercises should be

discon-tinued after the first trimester to minimize circulatory changes brought

on by pressure of the uterus on the vena cava. Any activity should be

discontinued if discomfort, significant shortness of breath, or pain in the

chest or abdomen appears (Box 6.4). Changes in body contour and balance will

alter the advised types of activities; abdominal trauma should be avoided.

Sitting in a hot tub or sauna after exercise is of con-cern to pregnant women. Possible hyperthermia may be teratogenic. Pregnant women might reasonably be advised to remain in saunas for no more than 15 minutes, and in hot tubs for no more than 10 minutes. In a hot tub, if a woman’s head, arms, shoulders, and upper chest are not submerged, there is less surface area to absorb heat.

Nutrition and Weight Gain

Concerns about adequate nutrition

and weight gain dur-ing pregnancy are common. Poor nutrition, obesity, and food

faddism are associated with poor perinatal outcome. Pica, or an inclination for nonnutritional substances suchas ice,

food starch, or clay or dirt, is often associated with anemia.

A complete nutritional assessment

is an important part of the initial antepartum assessment, including history of

dietary habits, special dietary issues or concerns, and weight trends. Anorexia

and bulimia increase risks for associated

Calculation of BMI is useful because it relates weight to height, allowing for

a better indirect measurement of body fat distribution than is obtained with

weight alone. Further, because of the “personalized nature” of an individual’s

BMI, it is often more useful in teaching a patient about diet and weight issues

than an abstract table.

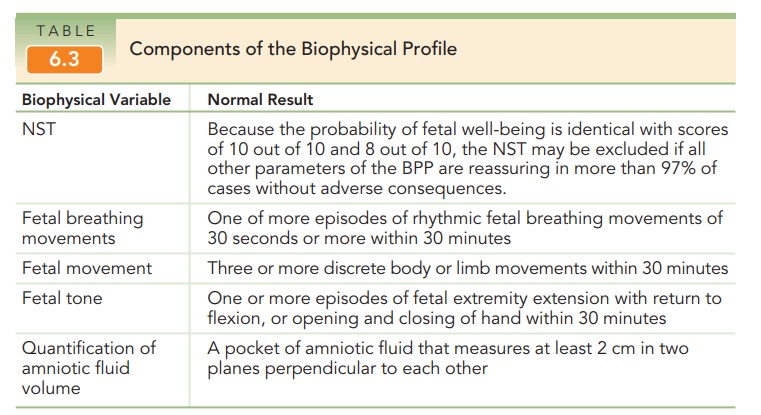

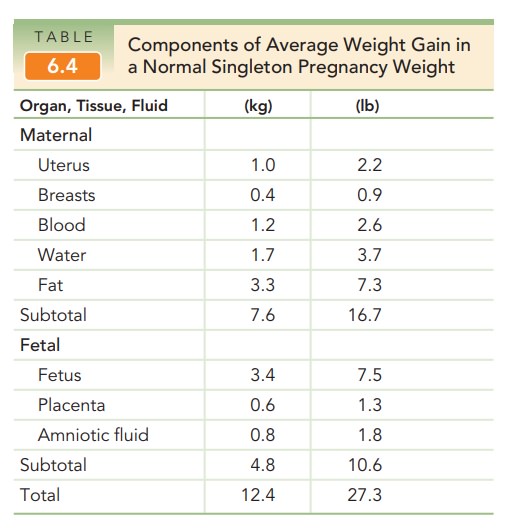

Recommendations for total weight

gain during preg-nancy and the rate of weight gain per month appropriate to

achieve it may be made based on a body mass index calculated for the

prepregnancy weight (see Table 6.3). The components that make up the average

weight gain in a normal singleton pregnancy are listed in Table 6.4. The

maternal component of this weight gain starts in the first trimester and

increases linearly after the second trimester. Fetal growth is most rapid in the

second half of pregnancy, with the normal fetus tripling its weight in the last

12 weeks.

Published recommended daily allowances (RDAs) for protein, minerals, and

vitamins are useful approxima-tions. It should be kept in mind, however, that

the RDAs are a combination of estimates and are values adjusted near the top of

the normal ranges to encompass the estimated needs of most women. Thus, many

women have an adequate diet for their individual needs, even though it does not

supply all the RDAs. Vitamin supplementation is appropriate for spe-cific

therapeutic indications, such as a patient’s inability or unwillingness to eat

a balanced, adequate diet, or clinical demonstration of a specific nutritional

risk. Except for iron, mineral supplementation is likewise not required in

other-wise healthy women; the National Academy of science rec-ommends 27 mg of

iron supplementation.

Financial problems, the inability

to get to a grocery store, and foodstuffs unique to a patient’s social group

that differ in substantial quantitative ways with respect to important

nutrients, may prevent some women from obtaining adequate nutrition, even if

the volume of food-stuffs seems sufficient. The WIC Federal Supplemental food

program, food stamp programs, and Aid for Families with Dependent Children are

resources that may help in these situations.

Breastfeeding

The benefits of breastfeeding include, for the newborn,

excellent nutrition and provision of immunologic protec-tion; and, for the

mother, more rapid uterine involution, economy, maternal–child bonding, to some

extent natural contraception, and, often, more rapid weight loss associ-ated

with extra calorie expenditure. Contraindications to breastfeeding include

certain maternal infections and use of medications. It is important to support

a woman who chooses not to breastfeed. The use of breast pumps and milk storage

may allow a mother to continue breastfeed-ing while continuing to work.

Sexual Activity

Sexual intercourse is not

restricted during a normal preg-nancy, although advice about more comfortable

positions in later pregnancy may be appreciated—for example, side-to-side or

the female-superior position. Sexual activity may be restricted or prohibited

under certain high-risk circumstances, such as known placenta previa, premature

rupture of membranes, or actual or history of preterm

labor (or delivery). Education of

the patient (and partner) about safe sex practices is as important in

antepartum as in regular gynecologic care.

Travel

Up to 36 weeks of gestation,

women can safely fly. Air travel is not recommended for women who have medical

or obstetric complications, such as hypertension, poorly controlled diabetes

mellitus, or sickle cell disease. This recommendation is not due to substantial

risk to either mother or fetus, but because of the likelihood that labor may

ensue away from home and customary health care providers. If a long trip near

term is planned, it is useful for the patient to carry a copy of her obstetric

record in case she requires obstetric care. When traveling, patients are

advised to avoid long periods of inactivity, such as sit-ting. Walking every 1

to 2 hours, even for short periods, promotes circulation, especially in the lower

legs, and decreases the risk of venous stasis and possible thrombo-embolism.

Additionally, preventive antiemetic medicine should be considered for pregnant

women with increased nausea. Education about the regular use of a seat belt is

especially important, with the seat belt worn low on the hip bones, between the

protuberant abdomen and the pelvis.

Teratogens

Many patient inquiries concern

the teratogenic potential of environmental exposures. Major birth defects are apparent at birth in

2% to 3% of the general population, and the possible occurrence of fetal

malformations or mental retardation is a frequent cause of anxiety among

pregnant women. Of these, about 5% may be a result of maternal exposure to

drugs or environmental chemicals, and only approximately 1% can be attributed

to pharma-ceutical agents. The most important determinants of the developmental

toxicity of an agent are timing, dose, and fetal susceptibility. Many agents

have teratogenic effects only if taken while the susceptible fetal organ system

is forming.

The health care provider may wish

to consult with or refer such patients to health care professionals with

special knowledge or experience in teratology and birth defects. The

Organization of Teratology Information Services provides information on

teratology issues and exposures in pregnancy (www.otis pregnancy.org).

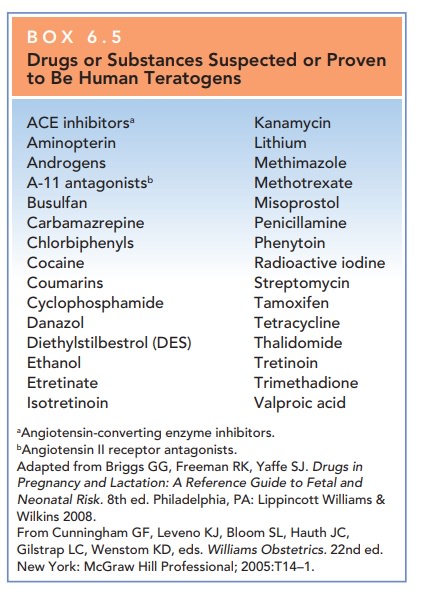

MEDICATIONS

Very few medications have been

proven to be true human teratogens (Box 6.5). Most commonly prescribed

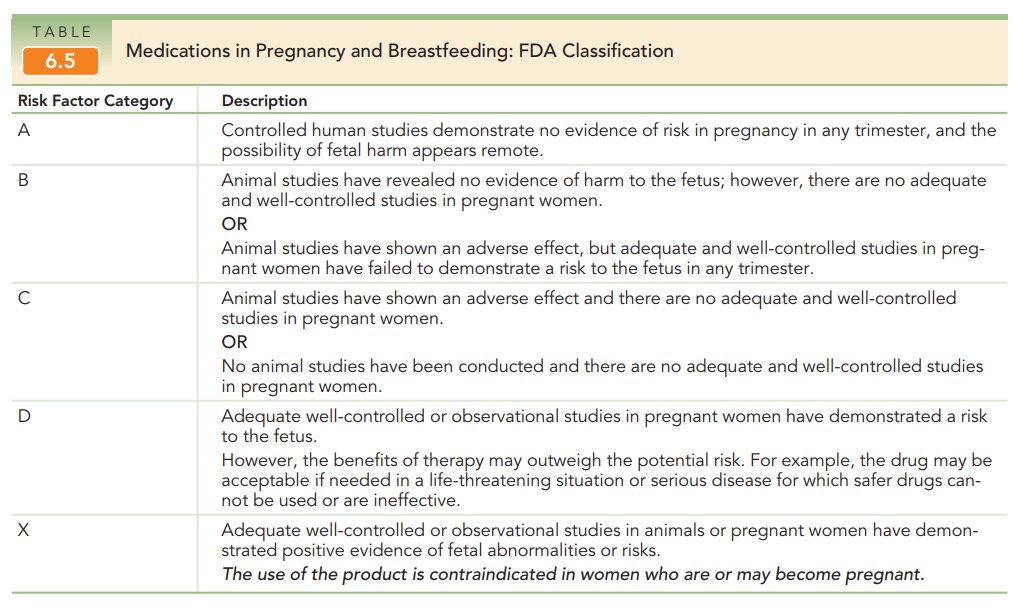

medica-tions are relatively safe in pregnancy. The Food and Drug Administration

assigns medications a pregnancy risk factor

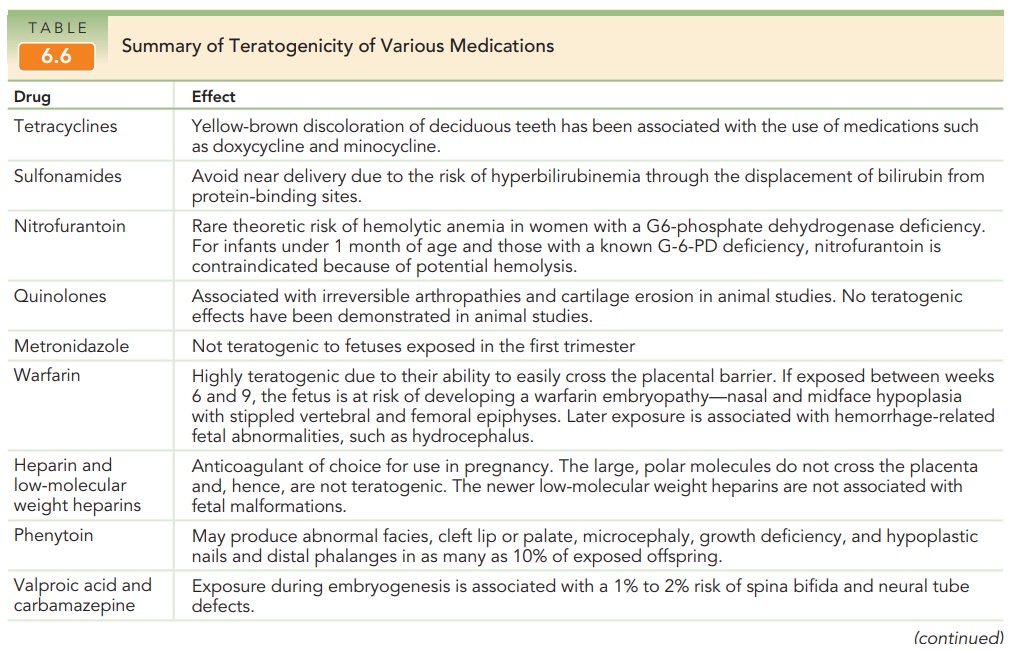

These pregnancy risk factors help guide

the appropriate use of medications in pregnancy (see Table 6.5). Table 6.6

provides a summary of the teratogenicity of many common medications.

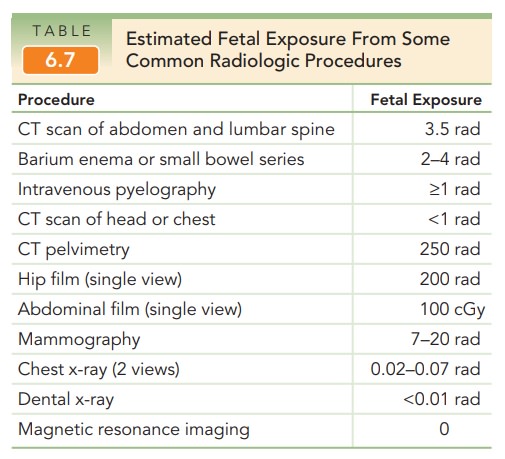

IONIZING RADIATION

Ionizing radiation exposure is

universal; most radiation originates from beyond the earth’s atmosphere, from

the land, and from endogenous radionuclides. The total radiation exposure from

these sources is approximately 125 mrads per year. Although radiation exposure

has the potential to cause gene mutations, growth impairment, chromosome damage

and malignancy, or fetal death, large doses are required to produce discernible

fetal effects. Large doses (10 rads) during the first two weeks after

fertilization are required to produce a deleterious effect. In the first trimester,

25 rads are required to pro-duce detectable damage, and 100 rads are required

later in pregnancy. Diagnostic radiation usually exposes the fetus to much less

than 5 rads, depending on the number of radiographs taken and the maternal site

examined (Table 6.7).

METHYL MERCURY

Industrial pollution is the major

source of mercury entry in our ecosystem. Large fish, such as tuna, shark, and

king mackerel, retain higher levels of mercury from the smaller fish and

organisms they consume. Hence, women who eat these fish are storing high levels

of mercury.

The FDA recommends that pregnant

women limit their ingestion of albacore tuna to 6 ounces per week or to 12

ounces per week of fish and shellfish varieties thought to be low in mercury.

HERBAL REMEDIES

Herbal remedies are not regulated

as prescription or over-the-counter drugs, the identity and quantity of their

ingredients are unknown, and there are virtually no studies of their

teratogenic potential. Because it is not possible to assess their safety, pregnant

women should be counseled to avoid these substances. Remedies contain-ing

substances with pharmaceutical properties that could theoretically have adverse

fetal affects include the following:

· Echinacea—causes

fragmentation of hamster sperm at high concentrations

· Black

cohosh—contains a chemical that acts like an estrogen

· Garlic

and willow barks—have anticoagulant properties

· Ginkgo—can

interfere with effects of monamine oxidase inhibitors; has anticoagulant

effects

· Real

licorice—has hypertensive and potassium-wasting effects

· Valerian—intensifies

the effects of prescription sleep aids

· Ginseng—interferes

with the effects of monamine oxidase inhibitors

· Blue

cohosh and pennyroyal—stimulate uterine muscu-lature; pennyroyal also can cause

liver damage, renal fail-ure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and

maternal death

ALCOHOL

Alcohol is the most common

teratogen to which a fetus is exposed, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy

is a leading preventable cause of mental retardation, develop-mental delay, and

birth defects in the fetus. There is substan-tial evidence that fetal toxicity

is dose-related and that the exposure time of greatest risk is the first

trimester. There is no established safe level of alcohol use during pregnancy.

Women who are pregnant or who are at risk for pregnancy should not drink

alcohol. Although consumption of small amounts of alcohol early in pregnancy is

unlikely to cause serious fetal problems, patients are best advised to refrain

from alcohol entirely.

Fetal

alcohol syndrome (FAS) is a congenital syn-drome

characterized by alcohol use during pregnancy and by three findings:

·

Growth restriction (which may

occur in the prenatal period, the postnatal period, or both)

·

Facial abnormalities, including

shortened palpebral fissures, low-set ears, midfacial hypoplasia, a smooth

philtrum, and a thin upper lip

·

Central nervous system

dysfunction, including micro-cephaly; mental retardation; and behavioral

disorders, such as attention deficit disorder

The exact risk incurred by

maternal alcohol use is difficult to establish, because the complex pattern of

symptoms asso-ciated with FAS can make diagnosis difficult. Consumption of 8 or

more drinks daily throughout pregnancy confers a 30% to 50% risk of having a

child with FAS. However, even low levels of alcohol consumption (two or fewer

drinks per week) have been associated with increased aggressive behavior in

children.

Tobacco Use

The risks of smoking during pregnancy have been well-established and include

risks to the fetus such as intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight,

and fetal mortality. It is important for the obstetrician to take advantage of

the pre-natal visits to educate patients about the risks of smoking for both

themselves and their newborns and to coordinate appropriate resources to help

patients quit. Counseling pro-grams are available to help patients quit

smoking. Nicotine replacement products may be considered, although their safety

in pregnancy has not been documented.

Substance Abuse

The use of illicit substances by

women of childbearing age has led to an increased number of neonates having had

in utero exposure and subsequent risk of adverse effects from a variety of

drugs. Fetal drug exposure often is unrecog-nized because of the lack of overt

symptoms or structural anomaly following birth.

Illicit drugs may reach the fetus

via placental transfer or may reach the newborn through breast milk. The

spe-cific effect on the fetus and newborn varies with the respec-tive

substances. An opiate-exposed fetus may experience withdrawal symptoms in utero

if the woman stops or when the woman goes through withdrawal, either

voluntarily or under supervision, or after birth when the delivery by way of

the placenta ceases.

Universal screening, using biologic

specimens, of women and newborns for substance abuse is not recom-mended.

However, all pregnant women should be asked at their first prenatal visit about

past and present use of alcohol, nicotine, and other drugs, including

recreational use of prescription and over-the-counter medications. Use of

specific screening questionnaires may improve detection rates. A woman who

acknowledges use of these substances should be counseled about the perinatal

implications of their use during pregnancy, and offered referral to an

appropriate drug-treatment program if chemical dependence is sus-pected.

Careful follow-up during the postpartum period is also recommended.

Related Topics