Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Ambulatory, Non operating Room, & Office-Based Anesthesia

Anesthesia: Special Considerations in Out of the Operating Room Locations

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN OUT OF THE OPERATING ROOM LOCATIONS

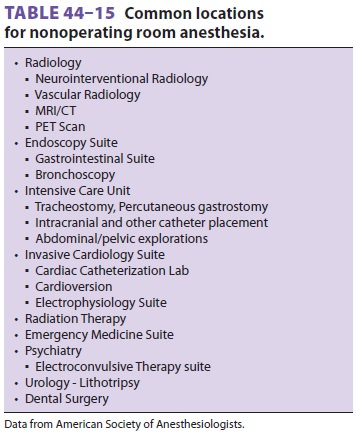

Anesthesia services are requested at various loca-tions throughout the

hospital facility; some of these are delineated in Table 44–15. As noted

through-out, routine anesthetic standards apply wherever the patient is

anesthetized. Out of the operating room patients often present with a wide

range of illnesses, unlike the elective patients gen-erally found in an

ambulatory setting. Furthermore,disposition postprocedure (whether discharge or

admission), needs appropriate coordination by the anesthesiologist for

postanesthesia care and/or safe transport from the remote unit.

Patients presenting to the gastrointestinal

endoscopy suite include healthy individuals for rou-tine diagnostic screenings,

as well as patients with fulminant cholangitis and sepsis or coexisting

dif-ficult airways. As always, the patient’s condition, as well as the specific

diagnostic/therapeutic pro-cedure, determines both the anesthetic techniques

(propofol deep sedation or general anesthesia vs. general anesthesia with LMA

or endotracheal tube) and the monitoring required.

General anesthesia is usually required in patients undergoing endoscopic

procedures for air-way and pulmonary pathology; an added complex-ity may

include the presence of a shared airway, and, in many patients, marginal

pulmonary status.

Patients undergoing cardiac catheterization

are routinely sedated by cardiologists without involvement of an anesthesiologist.

Occasionally, a patient with significant comorbidities, (eg, morbid obesity)

requires the presence of a qualified anes-thesia provider. General anesthesia

is often required for placement of aortic stents, which are increasingly being

performed by cardiologists in the cardiac cath-eterization laboratory.

Anesthesia staff should be prepared with arterial pressure monitoring and the

necessary vascular access to facilitate resuscitation, should emergent open

aneurysm repair be required.

Patients requiring electrophysiology

procedures for catheter-mediated arrhythmia ablation often need general

anesthesia. Such patients frequently have both systolic and diastolic heart

failure, leading to potential hemodynamic difficulties perioperatively. Sudden

hypotension can herald the development of pericardial tamponade secondary to

catheter perfo-ration of the heart. Other patients require sedation for the

placement of ICDs. Once placed, the device will be tested by inducing

ventricular fibrillation. During testing, deeper levels of sedation are

required, as the defibrillation shock can be frightening and very

uncomfortable. Likewise, anesthesia staff are called upon to provide anesthesia

for cardioversion of patients in atrial fibrillation. These patients usually have

associated cardiac diseases and require brief intravenous anesthetics to

facilitate cardioversion. Oftentimes, a transesophageal echocardiogram must be

performed prior to cardioversion to rule out clot in the left atrial appendage.

In such cases, anesthesia staff may also provide sedation for this procedure.

Determination as to whether a patient needs seda-tion or general anesthesia

with or without intubation is dependent upon routine patient assessment.

Children and some adults (ie, those that are claustrophobic,

developmentally disabled, or have conditions that prevent them to be still or

to lie flat) require anesthesia or sedation for MRI and computed tomography

(CT). Additionally, painful CT-guided biopsies may require anesthesia

man-agement. Anesthetic technique is dependent upon patient comorbidities.

MRI creates numerous problems for anesthe-sia

staff. First, all ferromagnetic materials must be excluded from the area of the

magnet. Most institu-tions have policies and training protocols to prevent

catastrophes (eg, oxygen tanks flying into the scan-ner). Second, all

anesthetic equipment must be compatible with the magnet in use. Third, patients

must be free of implants that could interact with the magnet, such as

pacemakers, vascular clips, ICDs, and infusion pumps. As with all out of the

operat-ing room anesthesia, the exact choice of technique is dependent upon the

patient’s comorbidities. Both deep sedation and general anesthesia approaches

with intubation or supraglottic airways can be used, depending on practitioner

preference and patient requirements.

Patients usually require general anesthesia

and tight blood pressure control to facilitate coiling and embolization of

cerebral aneurysms or arteriove-nous malformations. Patients taken to the radiology

suite for relief of portal hypertension via creation of a transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) are frequently hypovolemic, despite

profound ascites, and at risk of esophageal variceal bleeding and aspiration.

General anesthesia with intubation is preferred for management of the TIPS

procedure.

Anesthesia for electroconvulsive therapy is often provided in a separate

suite in the Psychiatry Unit or a monitored area in the hospital (eg, PACU).

Patient comorbidity, drug interactions with various psychotropic medications,

multiple anesthetic pro-cedures, and effects of anesthetic agents on the

qual-ity of electroconvulsive therapy also need to be taken into account.

Anesthesia staff are at times called to

provide anesthesia in the intensive care unit (ICU) for bed-side tracheostomy

or emergent chest and abdominal exploration in patients considered too

critically ill to tolerate transport to the operating room. In most of these

cases, the anesthesia staff generally employ ICU ventilator and monitors.

Intravenous agents are typically used along with muscle relaxants. When

performing anesthesia for bedside tracheostomy, it is important that the

endotracheal tube not be with-drawn from the trachea until end tidal CO 2 is mea-sured from the newly placed

tracheostomy tube.

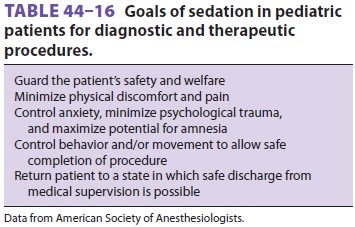

Pediatric patients deserve special mention;

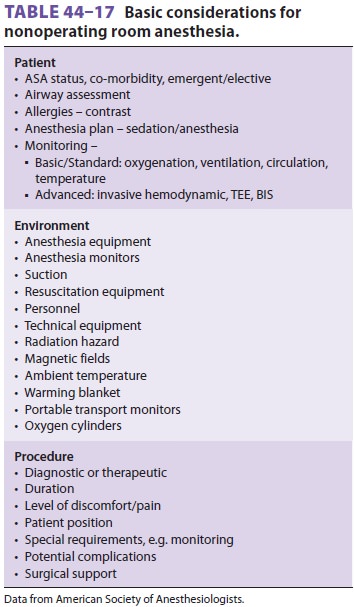

the (Table 44–16). Anesthesia

considerations for nonoperating room anesthesia are summarized in Table

44–17.

Related Topics