Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Stabilizers

Acute Mania

Acute

Mania

General Management Considerations

The goal

of treatment should be to suppress completely all symp-toms of mania and return

the patient to his or her mental status quo

ante. Mood, thinking and behavior should normalize. The patient should act and feel like herself or himself. For economic

or social reasons, it is sometimes necessary to discharge a patient before

total remission of symptoms has occurred. In such cases it is imperative that a

patient continues to take medication as pre-scribed and is protected from a

recrudescence of manic symp-toms or a rapid slide into acute depression.

Pharmacotherapy

The

mechanism of action of antimanic drugs is poorly understood. It is not as clear

what neural systems are involved in the mechanism of antimanic drugs. That few

significant changes in neurotransmit-ter levels have been measured suggests

that the site of action may be at the receptor, intracellular level, or

second-messenger systems.

Lithium

For many

patients with hypomania, lithium by itself can induce a total remission. For

patients with full-blown mania, however, an adjunctive antipsychotic or

antianxiety agent may be required to treat intolerable psychosis or excitement.

Lithium

is rapidly and completely absorbed after oral ad-ministration. It is not

protein bound and does not undergo me-tabolism. Peak plasma levels are achieved

within 1.5 to 2 hours for standard preparations or 4 to 4.5 hours for

slow-release forms. Lithium’s plasma half-life is 17 to 36 hours. Ninety-five

percent of the drug is excreted by the kidneys, with excretion proportion-ate

to plasma concentrations. Because lithium is filtered through the proximal

tubules, factors that decrease glomerular filtration rates will decrease

lithium clearance. Sodium also is filtered through the proximal tubules, so a

decrease in plasma sodium can increase lithium reabsorption and lead to

increased plasma lithium levels. Conversely, an increase in plasma lithium

levels can cause an increase in sodium excretion, depleting plasma so-dium.

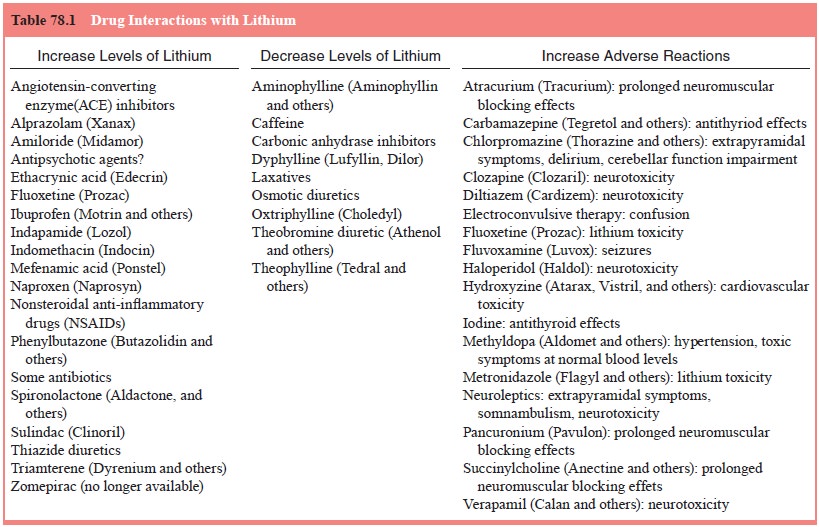

Many other drugs affect lithium levels (Table 78.1).

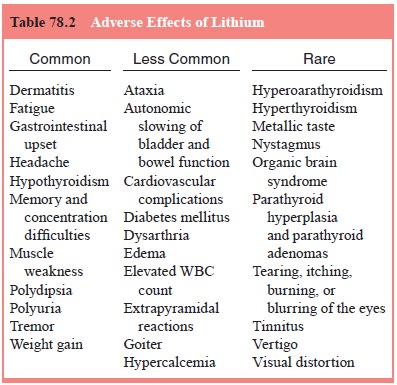

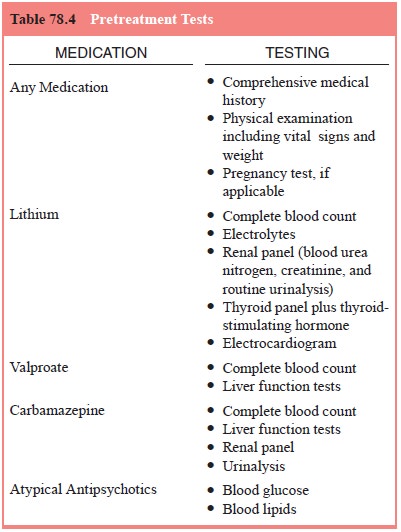

Tests

that should be done before lithium is started include a complete blood count,

electrocardiography, electrolyte determi-nations, and renal and thyroid panels

(Table 78.2). Lithium dos-age may be based on a plasma concentration sampled 12

hours after the last dose, or the drug may be gradually titrated to a dose that

is tolerated and within the range usually considered “ther-apeutic”. As with

any drug, approximately five half-lives must elapse for steady state to be

achieved. For an average adult, this takes about 5 days for lithium (longer in

the elderly or in patients with impaired renal function). To treat acute mania,

plasma concentrations should typically be greater than 0.8 mEq/L, but to avoid

toxicity, the level should not usually exceed 1.5 mEq/L. It is important to

know what other medications a pa-tient may be taking, because many drugs

interact with lithium and can lead to increased or decreased lithium levels and

possibly adverse effects (Table 78.2).

To reach

therapeutic levels rapidly in healthy younger pa-tients with normal renal and

cardiac function, the psychiatrist may prescribe 300 mg of lithium carbonate

four times daily from the outset, sampling the first plasma level after 5 days

(or sooner should toxic signs become apparent). Thereafter, the dose should be

adjusted to achieve a 12-hour plasma concentration between 0.8 and 1.3 mEq/L at

steady state.

In a

patient with mild hypomanic symptoms, by contrast, it may be wiser to begin

with a lower lithium dose, such as 300 mg b.i.d., taking longer to achieve

therapeutic levels but, at the same time, minimizing side effects that could

trouble the patient and hamper cooperation. Once steady state has been achieved

at thera-peutic concentrations and the patient is clinically stable, lithium

can be administered to most patients in a once-daily dose, usually at bedtime.

Not only is this schedule easier to remember, but it tends to decrease such

common side effects as tremor and polyuria.

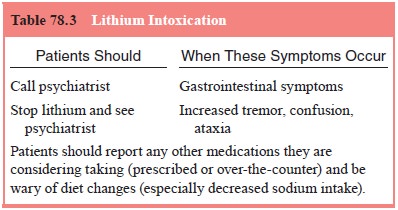

The most

common acute adverse effects from lithium are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,

postural tremor, polydipsia and polyuria (Table 78.2). If troublesome, these

can usually be miti-gated by a slower dosage increase or other measures. More

severe symptoms and signs, including confusion and ataxia, may herald lithium

intoxication and should prompt an immediate blood as-say and, if necessary,

temporary discontinuation or dosage re-duction (see Table 78.3).

Anxiolytic Agents

Among

current anxiolytic agents, benzodiazepines are usually se-lected as adjuncts to

treat acute mania because of their safety and efficacy. Benzodiazepines have a

wide margin of safety and can be safely administered in even very high doses,

suppressing potentially dangerous excitement and allowing patients much needed

sleep. When used together with an antipsychotic agent, benzodiazepines

counteract the antipsychotic agent’s tendency to provoke extrapy-ramidal

reactions and seizures. For lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg can be administered by mouth

or intramuscularly as frequently as hourly.

Valproate

Valproate

is available in the USA as valproic acid or divalproex sodium, a compound

containing equal parts valproic acid and sodium valproate. Divalproex is better

tolerated than valproic acid, has been studied more extensively and is more

commonly

used. All

valproate preparations are rapidly absorbed after oral administration, reaching

peak plasma levels within 2 to 4 hours of ingestion. Food may delay absorption

but does not affect bio-availability. Valproate is rapidly distributed and

highly bound (90%) to plasma proteins. Its half-life ranges from 9 to 16 hours,

depending on whether it is taken alone or with other medications, and it takes

1 to 4 days to attain steady state.

Experts

usually rank lithium as the treatment of choice for a patient with classic

mania, but divalproex is an accept-able first-line alternative. It may be used

singly in patients who cannot tolerate lithium. For patients who do not respond

to lithium, there are no secure data on whether divalproex should be added as

an adjunct or substituted, but many psychiatrists would choose the former in a

patient who appears to respond at least partially to lithium and the latter in

patients for whom lithium seems to afford no benefit. Increasingly,

psychiatrists are turning to divalproex first for manic patients with organic

brain impairment, rapid cycling, mixed or dysphoric mania, or comorbid

substance abuse (Bowden et al., 1994;

Calabrese et al., 1993).

Before

initiating divalproex, the psychiatrist should obtain a comprehensive medical

history and insure that a physical exam-ination has been performed, with

particular attention to sugges-tions of liver disease or bleeding abnormalities

(see Table 78.4).

Baseline

liver and hematological functions are measured before treatment, every 1 to 4

weeks for the first 6 months, and then every 3 to 6 months. Evidence of

hemorrhage, bruising, or a dis-order of hemostasis–coagulation suggests a

reduction of dosage or withdrawal of therapy. The drug should be discontinued

im-mediately in the presence of significant hepatic dysfunction.

A typical

starting dose for healthy adults is 750 mg/day in divided doses. The dose can

then be adjusted to achieve a 12-hour serum valproate concentration between 50

and 125 µg/mL. The time of dosing is

determined by possible side effects and, if tolerated, once-a-day dosing can be

employed. As with lith-ium, the antimanic response to valproate typically

occurs after 1 to 2 weeks.

Adverse

effects that appear early in the course of therapy are usually mild and

transient, and tend to resolve in time. Gas-trointestinal upset is probably the

most common complaint in patients taking valproate and tends to be less of a

problem with the enteric-coated divalproex sodium preparation. The

adminis-tration of a histamine H2 antagonist such as famotidine (Pepcid) or

cimetidine (Tagamet) may alleviate persistent gastrointestinal problems (Stoll et al., 1991). Other common complaints

include tremor, sedation, increased appetite and weight, and alopecia. Weight

gain is even more of a problem when other drugs are ad-ministered that also

promote weight gain, such as lithium, antip-sychotic and other antiepileptics.

Less common are ataxia, rashes and hematological dysfunction, such as

thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction. Platelet count usually recovers with

a dosage decrease, but the occurrence of thrombocytopenia or leukopenia may

necessitate the discontinuation of valproate. Serum hepatic transaminase

elevations are common, dose related, and usually self-limiting and benign.

Fatal hepatotoxicity is extremely rare, is usually restricted to young

children, and usually develops within the first 6 months of valproate therapy.

Other serious problems include pancreatitis and teratogenesis (McElroy et al., 1989). There is also a concern

that polycystic ovary syndrome, possibly associated with weight gain, may be a

risk for young women who take valproate. If at any point during administration

the side ef-fects of valproate become intolerable, the psychiatrist may need to

discontinue it and try one of the other treatments described in this section as

an alternative. If valproate is tolerated but not totally effective, the

psychiatrist might use one of the other treat-ments as an adjunct.

Carbamazepine

In light

of the less well-substantiated evidence for the efficacy of carbamazepine, we

place this anticonvulsant fourth in the antimania algorithm – behind lithium,

valproate, and olanzap-ine. The decision to move on to carbamazepine – and

whether to use it alone or in addition to lithium, valproate, or olanzapine –

hinges on the same treatment considerations listed earlier. If a patient has

been treated with one or more of these agents in a previous manic episode, that

experience may guide treatment of a

current episode.

Carbamazepine’s

absorption and metabolism are variable. Peak plasma levels occur within 4 to 6

hours after ingestion of the solid dosage form. Bioavailability is estimated at

85% but may be less when the drug is taken with meals. Eighty percent of plasma

carbamazepine is protein bound, and its half-life ranges from 5 to 26 hours

(after 3–4 weeks of treatment). Carbamazepine’s active metabolite,

10,11-epoxide, has a half-life of about 6 hours.

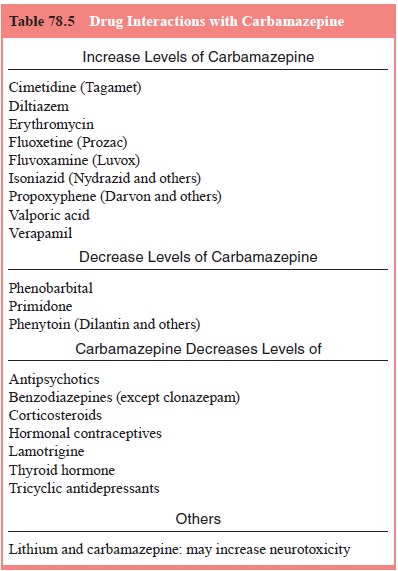

Carbamazepine

is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 2D6 system. It causes an

induction of the cytochrome P450 enzymes, often resulting in an increased rate

of its own metabolism over several weeks, as well as that of other drugs

metabolized by the P450 system (Table 78.5). Because of enzyme induction, the

dose of carbamazepine often must be raised after 2 to 4 months of treatment.

Steady state may be attained within 4 to 5 days, but when clearance increases

as a result of autoinduction, steady state may not be achieved for 3 to 4

weeks. Concomitant administration of drugs that inhibit P450 (see Table 78.6)

will increase plasma levels of carbamazepine. Conversely, drugs that induce

P450 enzymes – such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, or primidone – can decrease

carbamazepine levels. Before carbamazepine is started, baseline blood and

platelet counts, urinalysis, and liver and kidney function tests are in order

(see Table 78.4). Although earlier guidelines called for routine monitoring of

some or all of these indices, and some psychiatrists still obtain blood counts

once or twice during the first few months of treatment and when plasma

concentrations are sampled, a more general consensus at present is to instruct

patients and family members to contact the psychiatrist immediately if

petechiae, pallor, weakness, fever, or infection occur, at which time the

psychiatrist should order relevant tests.

Used as a

monotherapy, the typical starting dose for carbamazepine is 200 to 400 mg/day

in three or four divided doses, increased to 800 to 1000 mg/day by the end of

the first week. If clinical improvement is insufficient by the end of the

second week, and the patient has not had intolerable side effects to the drug,

increases to as high as 1600 mg/day may be considered. Although there are no

good studies of the correlation between blood level and clinical response, a

common target range for ma-nia is 4 to 15 ng/mL. If carbamazepine is combined

with lithium

or

neuroleptics, lower doses and blood levels of carbamazepine are often used. If

valproate and carbamazepine are administered simultaneously, blood levels of

each should be monitored care-fully because of complex interactions between the

two agents.

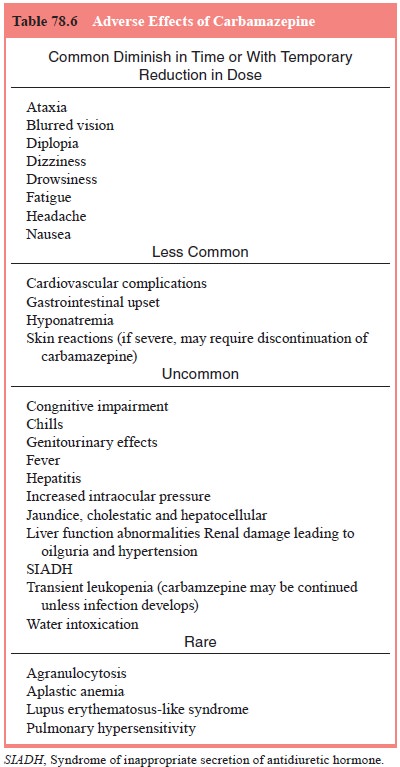

When the

dose of carbamazepine is built up rapidly, side effects are more likely. The

most common effects in the first cou-ple of weeks are drowsiness, dizziness,

ataxia, diplopia, nausea, blurred vision and fatigue (Table 78.6). These tend

to diminish in time or to respond to a temporary reduction in dose. Less

com-mon reactions include gastrointestinal upset, hyponatremia and a variety of

skin reactions, some of which are severe enough to require discontinuation of

carbamazepine. About 10% of patients experience transient leukopenia, but

unless infection develops, carbamazepine may be continued. More serious

hematopoietic re-actions, including aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis, are

rare.

Other Drug Treatments

Since

carbamazepine and valproate are efficacious for acute ma-nia, new antiepileptic

medications are often tested for mania. Lamotrigine, which appears useful in

maintenance, bipolar de-pression and rapid-cycling (see below), has not shown

efficacy in acute mania, with the exception of one recent double-blind trial

(Berk, 1999; Anand et al., 1999;

Bowden et al., 2000).

Nonpharmacotherapy: Electroconvulsive Therapy

When an acutely manic patient is unresponsive to or intolerant of medication, or if medication presents other risks (e.g., during preg-nancy), ECT should be seriously considered and may be lifesaving. Although there are no coherent theories about why ECT is effective in acute mania, it has been used for more than half a century, and there are widespread clinical impressions of its safety and efficacy.

Related Topics