Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Stabilizers

Acute Bipolar Depression

Acute

Bipolar Depression

General Management Considerations

Bipolar

depression is usually indistinguishable from other forms of major depression,

except that the episodes are typically shorter and more frequent. Other clues

that the disorder may be bipolar include onset at a young age, a positive

family history for bipolar disorder (particularly in first-degree relatives),

and the occurrence of a hypomanic phase before the onset of the depressive

episode.

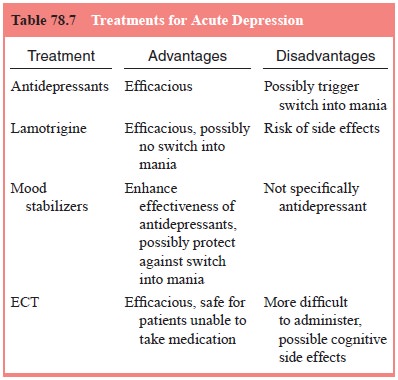

For the

most part, the treatment of a bipolar patient during an acute episode of

depression is similar to that of a nonbipolar patient. The same concerns about

protecting the patient from suicide and maintaining physical health and safety

apply, and for the most part, the same antidepressants or ECT will be useful

(Table 78.7). Because of fears about speeding up cycling and/or precipitat-ing

mania in patients with bipolar disorder, most doctors avoid prescribing

tricyclics in bipolar depression. The short section that follows addresses

issues unique to treatment of bipolar depression.

Pharmacotherapy

There is

a widespread clinical impression that administering some antidepressants to

bipolar patients can trigger switches into mania. Some experts also believe

that antidepressants speed up mood cycles, although this point is more

controversial. Because of both concerns, psychiatrists are often cautious about

prescrib-ing an antidepressant at the first sign of depression in a bipolar

patient. If symptoms are mild and short-lived, many clinicians choose watchful

waiting, while maintaining close contact to de-tect clinical deterioration.

Current

guidelines by the American Psychiatric Associa-tion list lithium, as well as

the anticonvulsant lamotrigine, as first-line monotherapy for acute bipolar

depression (Hirschfeld et al., 2002).

This is a result of recent research that suggests that lamotrigine may be an effective treatment for bipolar depression,

while carrying a low risk of triggering a switch into mania.

Lamotrigine

is completely absorbed after oral administra-tion, with a bioavailability of

98%, which is not affected by food. Peak plasma concentrations occur between

1.4 and 4.8 hours after administration. Lamotrigine is approximately 55%

protein bound, making clinical interactions with other protein-bound drugs

unlikely. Its half-life is 14 to 49 hours, with steady-state levels reached in

3 to 10 days.

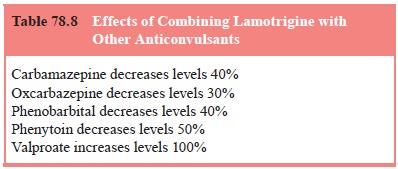

Lamotrigine

is metabolized predominately by glucuronic acid conjugation in the liver, with

the conjugate and the remaining 10% of the unmetabolized drug excreted in the

urine. Clearance is markedly increased with the administration of other drugs

that induce hepatic enzymes, including phenytoin, carbamazepine and

phenobarbital (Table 78.8). Adding lamotrigine to carbamazapine

can

decrease steady-state concentrations of lamotrigine by approximately 40%.

Adding lamotrigine to valproate, however, can decrease steady-state levels of

valproate by approximately 25%, while the steady-state levels of lamotrigine

increases approximately twofold. In this case, the starting dose of lamotrigine

should be lowered, and the titration made slowly.

The only

contraindication to lamotrigine use is hypersen-sitivity to the drug, though

there is a box warning about derma-tologic events, particularly rashes. These

rashes, that occurred in approximately 10% of patients, generally occur after 2

to 8 weeks and are usually macular, papular, or erythematous in nature. Of

those who develop a rash, one in 1000 adults can precede to a Stephens–Johnson

type syndrome. Because it is impossible to distinguish which rashes will

develop into this serious condition, it is advised to discontinue the

medication at any sign of drug-induced rash. Otherwise the most frequently

encountered side effects include dizziness, ataxia, somnolence, headache,

blurred vision, nausea, vomiting and diplopia.

To reduce

the risk of rash and other side effects lamotrigine should be started at low

doses and titrated slowly, especially if combined with valproate therapy.

Patients are commonly started on 25 to 50 mg p.o.q.d. doses for 2 weeks, with

doses increased by 25 to 50 mg every 1 to 2 weeks until maintenance levels

between 100 to 250 mg/day are reached. Maximum doses are lower with valproate

at about 100 to 150 mg/day. Initial labs for those un-dergoing lamotrigine

therapy should include liver function tests, renal function tests, a pregnancy

test if applicable and a complete medical work-up.

Probably

all available antidepressant drugs are effective in alleviating the symptoms of

depression in a bipolar patient, and in fact a recent 1-year retrospective

chart review by Altshuler and colleagues (2001) suggests that antidepressant

discontinuation may increase the risk of depressive relapse in bipolar

patients.

When a

patient is known to have bipolar disorder, admin-istration of an antidepressant

to reverse an acute depression is almost always used together with one of the

mood-stabilizing agents, usually lithium, valproate, carbamazepine (or a

combina-tion), or possibly one of the newer putative agents. Most bipo-lar

patients will be taking these drugs in maintenance therapy. Moreover, mood

stabilizers may enhance the effectiveness of the antidepressant and might

protect against the possibility of a switch into mania.

Nonpharmacotherapy: Electroconvulsive Therapy

ECT is a

useful alternative to antidepressants, particularly when a patient appears not

to be responding quickly or is intolerant of the medication. Early studies that

claimed that ECT works faster than medication in depressed patients are now

considered to be methodologically flawed. However, two later studies found a

more rapid decrease in depressive symptoms with ECT than is usually observed

with medications. In a total of 72 patients with major depression,

approximately six ECT treatments administered in a period of about 2 weeks led

to a decrease in mean Hamilton De-pression Rating Scale scores from between 24

and 30 to below 10 (Abrams et al.,

1991; Pettinati, 1994). The authors attributed the efficacy of treatment to the

use of high suprathreshold dosages. Sackeim and colleagues (1993) found that

higher dosage results in more rapid improvement in both bipolar and unipolar

depressed patients. There are indications that bilateral electrode placement is

superior to unilateral placement (Abrams et

al., 1991; Sackeim et al., 1993),

but there may be an increased risk of severe cogni-tive side effects with

bilateral ECT at ultrahigh dosages.

Related Topics