Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Amenorrhea and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

Failure to ovulate results in

either amenorrhea or irregu-lar uterine bleeding. Irregular bleeding that is

unrelated to anatomic lesions of the uterus is referred to as anovula-tory uterine bleeding. It is

most likely to occur in asso-ciation with anovulation as found in polycystic

ovarian disease, exogenous obesity, or adrenal hyperplasia.

Women

with hypothalamic amenorrhea (hypothalamic– pituitary dysfunction) and no

genital tract obstruction are in a state of estrogen deficiency. Estrogen

is inadequate to stimulategrowth and development of the endometrium. Therefore,

there is inadequate endometrium for uterine bleeding to occur. In contrast, women with oligo-ovulation and

anovulationwith abnormal uterine bleeding have constant, noncyclic blood

estrogen concentrations that stimulate growth and development of the

endometrium. Without the predictable effect of

ovulation,progesterone-induced changes do not occur. Initially, these patients

have amenorrhea because of the chronic, constant estrogen levels but,

eventually, the endometrium outgrows its blood supply and sloughs from the

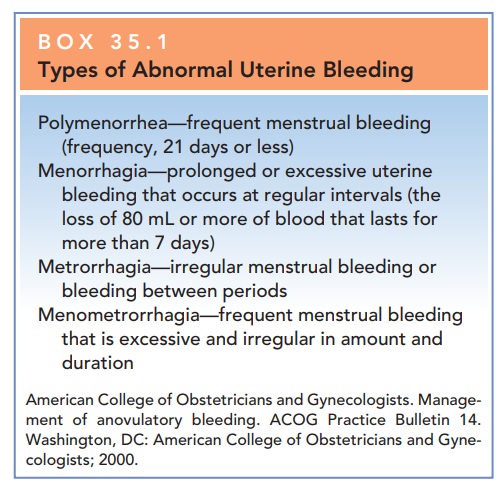

uterus at irregular times and in unpredictable amounts (see Box 35.1).

When there is chronic stimulation

of the endometrium from low plasma concentrations of estrogens, the episodes of

uterine bleeding are infrequent and light. Alternatively, with chronic

stimulation of the endometrium from increased plasma concentrations of

estrogens, the episodes of uterine bleeding can be frequent and heavy. Because

amenorrhea and abnormal uterine bleeding both result from anovulation, it is

not surprising that they can occur at different times in the same patient.

Subtle alterations in the

mechanisms of ovulation can produce abnormal cycles, even when ovulation occurs

(e.g., the luteal phase defect). In the luteal

phase defect, ovulation does occur; however, the corpus luteum of the ovary

is not fully developed to secrete adequate quantities of progesterone to

support the endometrium for the usual 13 to 14 days and is not adequate to

support a pregnancy if conception does occur. The menstrual cycle is shortened,

and menstruation occurs earlier than expected. Although this is not classical

anovulatory uterine bleeding, it is con-sidered to be in the same category.

Another example is mid-cycle spotting, in which patients report bleeding at the

time of ovulation. In the absence of demonstrable pathology, this self-limited

bleeding can be attributed to the sudden drop in estrogen level that occurs at

this time of the cycle.

Diagnosis of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Diagnosis of abnormal uterine

bleeding should be sus-pected when vaginal bleeding is not regular, not

pre-dictable, and not associated with premenstrual signs and symptoms that

usually accompany ovulatory cycles. These signs and symptoms include breast

fullness, abdominal bloating, mood changes, edema, weight gain, and uterine

cramps.

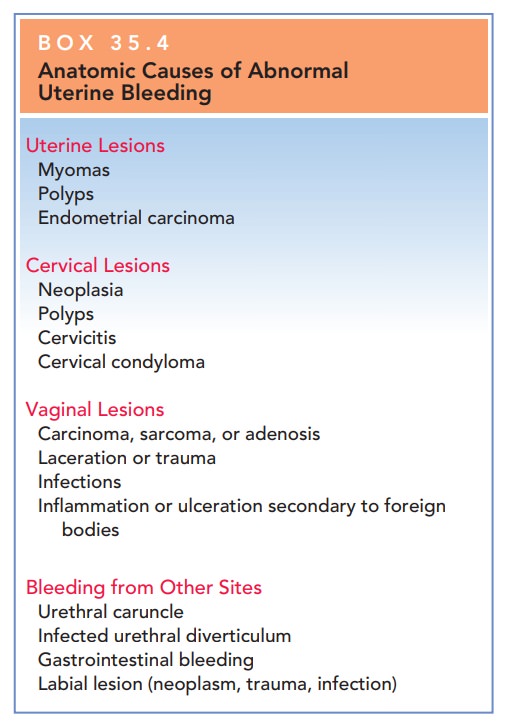

Before

anovulatory uterine bleeding can be diagnosed, anatomic causes including

neoplasia should be excluded.

In a reproductive-aged woman,

complications of pregnancy as a cause of irregular vaginal bleeding should be

excluded. Other anatomic causes of irregular vaginal bleeding include uterine

leiomyomata, inflammation or infection of the gen-ital tract, hyperplasia or

carcinoma of the cervix or endo-metrium, cervical and endometrial polyps, and

lesions of the vagina (Box 35.4). Pelvic ultrasonography or sonohysterog-raphy

may assist in diagnosing these lesions. Women with organic causes for bleeding

may have regular ovulatory cycles with superimposed irregular bleeding.

If the diagnosis is uncertain

based on history and phys-ical examination alone, a woman may keep a basal body

temperature chart for 6 to 8 weeks to look for the shift in the basal

temperature that occurs with ovulation. An ovu-lation predictor kit may also be

used. Luteal phase pro-gestin may also be measured. In cases of anovulation and

abnormal bleeding, an endometrial biopsy may reveal endometrial hyperplasia.

Because abnormal uterine bleed-ing results from chronic, unopposed estrogenic

stimulation of the endometrium, the endometrium appears prolifera-tive or, with

prolonged estrogenic stimulation, hyperplas-tic. Without treatment, these women

are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.

Treatment of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

The risks to a woman with anovulatory

uterine bleeding include anemia, incapacitating blood loss, endometrial

hyperplasia, and carcinoma. Uterine bleeding can be severe enough to require

hospitalization. Both hemor rhage and endometrial hyperplasia can be prevented

by appropriate management.

Box 35.4

Anatomic Causes of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Uterine Lesions

Myomas

Polyps

Endometrial

carcinoma

Cervical Lesions

Neoplasia

Polyps

Cervicitis

Cervical

condyloma

Vaginal Lesions

Carcinoma,

sarcoma, or adenosis

Laceration

or trauma

Infections

Inflammation

or ulceration secondary to foreign bodies

Bleeding from Other Sites

Urethral

caruncle

Infected

urethral diverticulum

Gastrointestinal

bleeding

Labial

lesion (neoplasm, trauma, infection)

The

primary goal of treatment of anovulatory uterine bleed-ing is to ensure regular

shedding of the endometrium and conse-quent regulation of uterine bleeding. If

ovulation is achieved,conversion of the proliferative endometrium into

secretory endometrium will result in predictable uterine withdrawal bleeding.

A progestational agent may be

administered for a mini-mum of 10 days. The most commonly used agent is

me-droxyprogesterone acetate. When the progestational agent is discontinued,

uterine withdrawal bleeding ensues, thereby mimicking physiologic withdrawal of

progesterone.

As an alternative, administration

of oral contraceptives suppresses the endometrium and establishes regular,

pre-dictable withdrawal cycles. No particular oral contraceptive preparation is

better than any of the others for this purpose. Women who take oral

contraceptives as treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding often resume abnormal

uterine bleeding after therapy is discontinued.

If a patient is being treated for

a particularly heavy bleeding episode, once organic pathology has been ruled

out, treatment should focus on two issues: (1) control of the acute episode,

and (2) prevention of future recurrences. Both high-dose estrogen and progestin

therapy as well as combination treatment (oral contraceptive pills, four per

day) have been advocated for management of heavy abnor-mal bleeding in the

acute phase. Long-term preventive management may include either intermittent

progestin treatment or oral contraceptives. Uterine bleeding that does not

respond to medical therapy often is managed sur-gically with endometrial

ablation or hysterectomy. Before proceeding with endometrial ablation, one must

rule out endometrial carcinoma.

Related Topics