Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Substance Abuse

Types of Substances and Treatment

TYPES OF SUBSTANCES AND TREATMENT

The classes of mood-altering substances have some similari-ties and

differences in terms of intended effect, intoxication effects, and withdrawal

symptoms. Treatment approaches after detoxification, however, are quite

similar. This section presents a brief overview of seven classes of substances

and the effects of intoxication, overdose, withdrawal, and detox-ification, and

it highlights important elements of which the nurse should be aware.

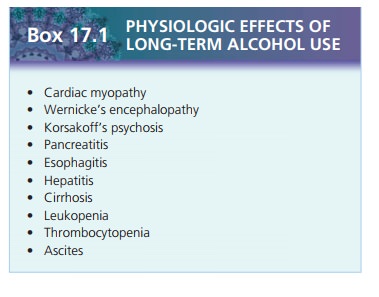

Alcohol

Intoxication and Overdose

Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant that is absorbed

rapidly into the bloodstream. Initially, the effects are relaxation and loss of

inhibitions. With intoxication, there is slurred speech, unsteady gait, lack of

coordination, and impaired attention, concentration, memory, and judg-ment.

Some people become aggressive or display inappro-priate sexual behavior when

intoxicated. The person who is intoxicated may experience a blackout.

An overdose, or excessive alcohol intake in a short period, can

result in vomiting, unconsciousness, and respiratory depression. This

combination can cause aspi-ration pneumonia or pulmonary obstruction.

Alcohol-induced hypotension can lead to cardiovascular shock and death.

Treatment of an alcohol overdose is similar to that for any central nervous

system depressant: gastric lavage or dialysis to remove the drug and support of

respi-ratory and cardiovascular functioning in an intensive care unit. The

administration of central nervous system stimu-lants is contraindicated (Lehne,

2006).

Withdrawal and Detoxification

Symptoms of withdrawal usually begin 4 to 12 hours after cessation

or marked reduction of alcohol intake. Symp-toms include coarse hand tremors,

sweating, elevated pulse and blood pressure, insomnia, anxiety, and nausea or

vomiting. Severe or untreated withdrawal may progress to transient

hallucinations, seizures, or delirium—called delirium tremens (DTs). Alcohol

withdrawal usually peaks on the second day and is over in about 5 days

(American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). This can vary, how-ever, and

withdrawal may take 1 to 2 weeks.

Because alcohol withdrawal can be life-threatening, detoxification

needs to be accomplished under medical supervision. If the client’s withdrawal

symptoms are mild and he or she can abstain from alcohol, he or she can be

treated safely at home. For more severe withdrawal or for clients who cannot

abstain during detoxification, a short admission of 3 to 5 days is the most

common setting. Some psychiatric units also admit clients for detoxification,

but this is less common.

Safe withdrawal is usually accomplished with the administration of

benzodiazepines such as lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), or

diazepam (Valium) to suppress the withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal can be

accomplished by fixed-schedule dosing known as tapering or symptom-triggered

dosing in which the presence and severity of withdrawal symptoms determine the

amount of medication needed and the frequency of administration. Often, the

protocol used is based on an assessment tool such as the Clinical Institute

Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale. Total scores less than 8 indicate mild

withdrawal; scores from 8 to 15 indicate moderate withdrawal (marked arousal);

and scores greater than 15 indicate severe withdrawal. Clients on symptom-triggered

dosing receive medication based on scores of this scale alone, whereas clients

on fixed-dose tapers also can receive additional doses depending on the level

of scores from this scale. Both methods of medicating clients are safe and

effective.

Sedatives, Hypnotics, and Anxiolytics

Intoxication and Overdose

This class of drugs includes all central nervous system

depressants: barbiturates, nonbarbiturate hypnotics, and anxiolytics,

particularly benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines and barbiturates are the most

frequently abused drugs in this category (Ciraulo & Sarid-Segal, 2005). The

intensity of the effect depends on the particular drug. The effects of the

drugs, symptoms of intoxication, and withdrawal symptoms are similar to those

of alcohol. In the usual pre-scribed doses, these drugs cause drowsiness and

reduce anxiety, which is the intended purpose. Intoxication symp-toms include

slurred speech, lack of coordination, unsteady gait, labile mood, impaired

attention or memory, and even stupor and coma.

Benzodiazepines alone, when taken orally in overdose, are rarely

fatal, but the person is lethargic and confused. Treatment includes gastric

lavage followed by ingestion of activated charcoal and a saline cathartic;

dialysis can be used if symptoms are severe (Lehne, 2006). The client’s

confusion and lethargy improve as the drug is excreted.

Barbiturates, in contrast, can be lethal when taken in overdose.

They can cause coma, respiratory arrest, cardiac failure, and death. Treatment

in an intensive care unit is required using lavage or dialysis to remove the

drug from the system and to support respiratory and cardiovascular function.

![]()

![]()

Withdrawal and Detoxification

The onset of withdrawal symptoms depends on the half-life of the

drug . Medications such as lora-zepam, whose actions typically last about 10

hours, pro-duce withdrawal symptoms in 6 to 8 hours; longer-acting medications

such as diazepam may not produce with-drawal symptoms for 1 week (APA, 2000).

The withdrawal syndrome is characterized by symptoms that are the oppo-site of

the acute effects of the drug: that is, autonomic hyperactivity (increased

pulse, blood pressure, respira-tions, and temperature), hand tremor, insomnia,

anxiety, nausea, and psychomotor agitation. Seizures and halluci-nations occur

only rarely in severe benzodiazepine with-drawal (Ciraulo & Sarid-Segal,

2005).

Detoxification from sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolyt-ics is often

managed medically by tapering the amount of the drug the client receives over a

period of days or weeks, depending on the drug and the amount the client had

been using. Tapering, or

administering decreasing doses of a medication, is essential with barbiturates

to prevent coma and death that occur if the drug is stopped abruptly. For

example, when tapering the dosage of a benzodiazepine, the client may be given

Valium, 10 mg four times a day; the dose is decreased every 3 days, and the

number of times a day the dose is given also is decreased until the cli-ent

safely withdraws from the drug.

Stimulants (Amphetamines, Cocaine)

Stimulants are drugs that stimulate or

excite the central nervous system.

Although the DSM-IV-TR categorizes

amphetamines, cocaine, and central nervous system stim-ulants separately, the

effects, intoxication, and withdrawal symptoms of these drugs are virtually

identical. They are grouped together here for this reason.

Stimulants have limited clinical use (with the exception of

stimulants used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder;) and a high

potential for abuse. Amphetamines (uppers) were popular in the past; they were

used by people who wanted to lose weight or to stay awake. Cocaine, an illegal

drug with virtually no clinical use in medicine, is highly addictive and a

popular recre-ational drug because of the intense and immediate feeling of

euphoria it produces.

Methamphetamine is particularly dangerous. It is highly addictive

and causes psychotic behavior. Brain damage related to its use is frequent,

primarily as a result of the substances used to make it—that is, liquid

agricul-tural fertilizer. The percentage of people admitted to inpatient

settings for methamphetamine abuse had increased in 49 of the 50 states in the

United States from 2000 to 2005. Use of methamphetamine, however, seems to have

peaked and actually declined in the past few years (Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Adminis-tration, 2009).

Intoxication and Overdose

Intoxication from stimulants develops rapidly; effects include the

high or euphoric feeling, hyperactivity, hyper-vigilance, talkativeness,

anxiety, grandiosity, hallucina-tions, stereotypic or repetitive behavior,

anger, fighting, and impaired judgment. Physiologic effects include

tachy-cardia, elevated blood pressure, dilated pupils, perspira-tion or chills,

nausea, chest pain, confusion, and cardiac dysrhythmias. Overdoses of

stimulants can result in sei-zures and coma; deaths are rare (Jaffe, Ling,

& Rawson, 2005). Treatment with chlorpromazine (Thorazine), an

antipsychotic, controls hallucinations, lowers blood pres-sure, and relieves

nausea (Lehne, 2006).

Withdrawal and Detoxification

Withdrawal from stimulants occurs within a few hours to several

days after cessation of the drug and is not life-threatening. Marked dysphoria

is the primary symptom and is accompanied by fatigue, vivid and unpleasant

dreams, insomnia or hypersomnia, increased appetite, and psychomotor

retardation or agitation. Marked withdrawal symptoms are referred to as

“crashing”; the person may experience depressive symptoms, including suicidal

ide-ation, for several days. Stimulant withdrawal is not treated

pharmacologically.

Cannabis (Marijuana)

Cannabis sativa is the hemp plant that is

widely cultivated for its fiber used

to make rope and cloth and for oil from its seeds. It has become widely known

for its psychoactive resin (Hall & Degenhardt, 2005). This resin contains

more than 60 substances, called cannabinoids, of which d-9-tetrahydrocannabinol is

thought to be responsible for most of the psychoactive effects. Marijuana

refers to the upper leaves, flowering tops, and stems of the plant; hashish is

the dried resinous exudate from the leaves of the female plant. Cannabis is

most often smoked in cigarettes (joints), but it can be eaten.

Cannabis is the most widely used illicit substance in the United

States. Research has shown that cannabis has short-term effects of lowering

intraocular pressure, but it is not approved for the treatment of glaucoma. It

also has been studied for its effectiveness in relieving the nausea and

vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy and the anorexia and weight loss

of AIDS. Currently, two cannabi-noids, dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone

(Cesamet), have been approved for treating nausea and vomiting from can-cer

chemotherapy.

Intoxication and Overdose

Cannabis begins to act less than 1 minute after inhala-tion. Peak

effects usually occur in 20 to 30 minutes and last at least 2 to 3 hours. Users

report a high feeling simi-lar to that with alcohol, lowered inhibitions,

relaxation, euphoria, and increased appetite. Symptoms of intoxica-tion include

impaired motor coordination, inappropriate laughter, impaired judgment and

short-term memory, and distortions of time and perception. Anxiety, dyspho-ria,

and social withdrawal may occur in some users. Physiologic effects, in addition

to increased appetite, include conjunctival injection (bloodshot eyes), dry

mouth, hypotension, and tachycardia. Excessive use of cannabis may produce

delirium or, rarely, cannabis-in-duced psychotic disorder, both of which are

treated symptomatically. Overdoses of cannabis do not occur (Hall &

Degenhardt, 2005).

Withdrawal and Detoxification

Although some people have reported withdrawal symp-toms of muscle

aches, sweating, anxiety, and tremors, no clinically significant withdrawal

syndrome is identified (Lehne, 2006).

Opioids

Opioids are popular drugs of abuse

because they desensi-tize the user to both physiologic and psychologic pain and

induce a sense of euphoria and well-being. Opioid com-pounds include both

potent prescription analgesics such as morphine, meperidine (Demerol), codeine,

hydromor-phone, oxycodone, methadone, oxymorphone, hydro-codone, and

propoxyphene as well as illegal substances such as heroin and normethadone.

People who abuse opi-oids spend a great deal of their time obtaining the drugs;

they often engage in illegal activity to get them. Health care professionals

who abuse opioids often write prescrip-tions for themselves or divert

prescribed pain medication for clients to themselves (APA, 2000).

Intoxication and Overdose

Opioid intoxication develops soon after the initial euphoric

feeling; symptoms include apathy, lethargy, listlessness, impaired judgment,

psychomotor retardation or agitation, constricted pupils, drowsiness, slurred

speech, and impaired attention and memory. Severe intoxication or opioid

over-dose can lead to coma, respiratory depression, pupillary con-striction,

unconsciousness, and death. Administration of naloxone (Narcan), an opioid antagonist,

is the treatment of choice because it reverses all signs of opioid toxicity.

Nalox-one is given every few hours until the opioid level drops to nontoxic;

this process may take days (Lehne, 2006).

Withdrawal and Detoxification

Opioid withdrawal develops when drug intake ceases or decreases

markedly, or it can be precipitated by the admin-istration of an opioid

antagonist. Initial symptoms are anxi-ety, restlessness, aching back and legs,

and cravings for more opioids (Jaffe & Strain, 2005). Symptoms that develop

as withdrawal progresses include nausea, vomiting, dysphoria, lacrimation,

rhinorrhea, sweating, diarrhea, yawning, fever, and insomnia. Symptoms of

opioid withdrawal cause sig-nificant distress but do not require pharmacologic

interven-tion to support life or bodily functions. Short-acting drugs such as

heroin produce withdrawal symptoms in 6 to 24 hours; the symptoms peak in 2 to

3 days and gradually sub-side in 5 to 7 days. Longer-acting substances such as

metha-done may not produce significant withdrawal symptoms for 2 to 4 days, and

the symptoms may take 2 weeks to subside. Methadone can be used as a

replacement for the opioid, and the dosage is then decreased over 2 weeks.

Substitution of methadone during detoxification reduces symptoms to no worse

than a mild case of flu (Lehne, 2006). Withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety,

insomnia, dysphoria, anhedonia, and drug craving may persist for weeks or

months.

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens are substances that distort

the user’s percep-tion of reality and produce symptoms similar to psychosis,

including hallucinations (usually visual) and depersonal-ization. Hallucinogens

also cause increased pulse, blood pressure, and temperature; dilated pupils;

and hyperreflexia. Examples of hallucinogens are mescaline, psilocybin,

lyser-gic acid diethylamide, and “designer drugs” such as Ecstasy. PCP,

developed as an anesthetic, is included in this section because it acts

similarly to hallucinogens.

Intoxication and Overdose

Hallucinogen intoxication is marked by several maladap-tive

behavioral or psychologic changes: anxiety, depression, paranoid ideation,

ideas of reference, fear of losing one’s mind, and potentially dangerous

behavior such as jumping ![]()

![]() out a window in the belief that one can fly

(Jones, 2005). Physiologic symptoms include sweating, tachycardia,

pal-pitations, blurred vision, tremors, and lack of coordination. PCP

intoxication often involves belligerence, aggression, impulsivity, and

unpredictable behavior.

out a window in the belief that one can fly

(Jones, 2005). Physiologic symptoms include sweating, tachycardia,

pal-pitations, blurred vision, tremors, and lack of coordination. PCP

intoxication often involves belligerence, aggression, impulsivity, and

unpredictable behavior.

Toxic reactions to hallucinogens (except PCP) are primar-ily

psychologic; overdoses as such do not occur. These drugs are not a direct cause

of death, although fatalities have occurred from related accidents, aggression,

and suicide. Treatment of toxic reactions is supportive. Psychotic reactions

are managed best by isolation from external stimuli; physical restraints may be

necessary for the safety of the client and others. PCP toxic-ity can include

seizures, hypertension, hyperthermia, and respiratory depression. Medications

are used to control sei-zures and blood pressure. Cooling devices such as

hyper-thermia blankets are used, and mechanical ventilation is used to support

respirations (Lehne, 2006).

Withdrawal and Detoxification

No withdrawal syndrome has been identified for halluci-nogens,

although some people have reported a craving for the drug. Hallucinogens can

produce flashbacks, which are transient recurrences of perceptual disturbances

like those experienced with hallucinogen use. These episodes occur even after

all traces of the hallucinogen are gone and may persist for a few months up to

5 years.

Inhalants

Inhalants are a diverse group of drugs

that include anes-thetics, nitrates, and organic solvents that are inhaled for

their effects. The most common substances in this category are aliphatic and

aromatic hydrocarbons found in gasoline, glue, paint thinner, and spray paint.

Less frequently used halogenated hydrocarbons include cleaners, correction

fluid, spray can propellants, and other compounds contain-ing esters, ketones,

and glycols (APA, 2000). Most of the vapors are inhaled from a rag soaked with

the compound, from a paper or plastic bag, or directly from the container.

Inhalants can cause significant brain damage, peripheral nervous system damage,

and liver disease.

Intoxication and Overdose

Inhalant intoxication involves dizziness, nystagmus, lack of

coordination, slurred speech, unsteady gait, tremor, muscle weakness, and

blurred vision. Stupor and coma can occur. Significant behavioral symptoms are

belliger-ence, aggression, apathy, impaired judgment, and inability to

function. Acute toxicity causes anoxia, respiratory depression, vagal

stimulation, and dysrhythmias. Death may occur from bronchospasm, cardiac

arrest, suffocation, or aspiration of the compound or vomitus (Crowley &

Sakai, 2005). Treatment consists of supporting respiratory and cardiac

functioning until the substance is removed from the body. There are no

antidotes or specific medica-tions to treat inhalant toxicity.

Withdrawal and Detoxification

There are no withdrawal symptoms or detoxification pro-cedures for

inhalants as such, although frequent users report psychologic cravings. People

who abuse inhalants may suffer from persistent dementia or inhalant-induced

disorders such as psychosis, anxiety, or mood disorders even if the inhalant

abuse ceases. These disorders are all treated symptomatically (Crowley &

Sakai, 2005).

Related Topics