Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Tic Disorders

Treatment of Cooccurring Psychiatric Disorders in TouretteŌĆÖs Disorder

Treatment of Cooccurring

Psychiatric Disorders in TouretteŌĆÖs Disorder

Treatment of Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Nonpharmacological Approaches

The nonpharmacological approaches to ADHD in

TouretteŌĆÖs disorder are similar to approaches in children without TouretteŌĆÖs

disorder. The presence both at home and at school of a structured environment,

consistent behavioral management, and a gener-ally positive, rewarding

atmosphere can produce significant im-provement in ADHD symptoms. Increasingly,

there are specific programs for children with ADHD that go beyond basic

positive programming and include more intensive and specific behavioral

approaches.

Pharmacological Treatments

The two major difficulties in the treatment of ADHD

in TouretteŌĆÖs disorder are the risk of side effects from the stimulants and

desipramine, arguably the most potent treatment agents for ADHD and the lack of

adequate alternatives.

Stimulants

In the early 1970s, a number of reports of

induction or exacerbation of tics by stimulant medications raised concerns

about the role of stimulants as a cause of TouretteŌĆÖs disorder. At that time,

the con-cern was that stimulants could be causing tics de novo or that in-creases in tic severity would endure even if

stimulant medications were discontinued. Concurrent with these reports, other

authors noted that tic induction or exacerbation was relatively infrequent and

that the beneficial effects in some patients with TouretteŌĆÖs dis-order

outweighed any negative impact on tic severity.

As a result, stimulants have been used infrequently

for ADHD in TouretteŌĆÖs disorder. However, results of short-term and long-term

double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with stimulants in TouretteŌĆÖs disorder

are positive and support a role for stimu-lants in some patients with

TouretteŌĆÖs disorder plus ADHD. In-creasingly, psychiatrists are cautiously, and

with fully informed consent, using stimulant medication in selected children

and adolescents with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder and ADHD. In the patient in whom tics

are increased by stimulants, combined treatment with stimulants and

tic-suppressing agents can be used.

More recently, in a large (N 5 136) multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled

trial, children with ADHD and a chronic tic disorder were randomly assigned to

clonidine alone, methylphenidate alone, clonidine plus methylphenidate or

placebo for the treatment of their ADHD. The results suggest that the active

treatments were superior to placebo, with the combination treatment being the

most effective. With respect to worsening of tic severity the percentage of

children with worsening of tics was similar in each of the medication

conditions including placebo. For methylphenidate, 20% reported tic increases

compared with 26% on clonidine alone and 22% on placebo. Interestingly tic

severity lessened in all active treatment groups even in the methylphenidate

group. Other side effects were predictable with sedation commonly associated

with clonidine treatment (The Tourette Syndrome Study Group, 2002). Given the

controversy regarding the coadministration of clonidine and methylphenidate it

is important to note the absence of cardiac toxicity in children on combined medication.

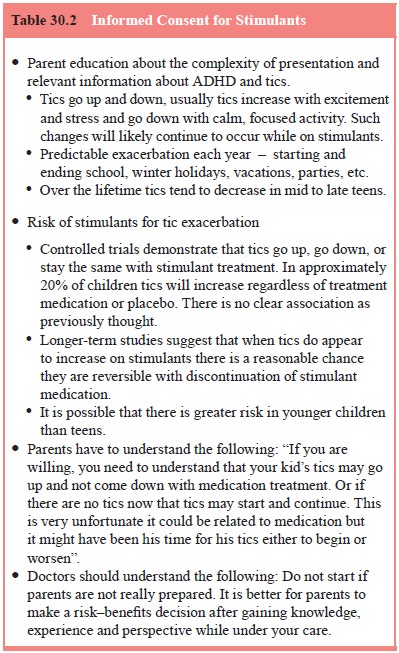

Given the above, informed consent prior to

initiating stim-ulant medication should include information regarding the risks

for new onset of tics or tic exacerbations. In Table 30.2 is a listing of

topics that might be useful to address during informed consent. This listing is

not intended to be a comprehensive or exhaustive.

Desipramine

Desipramine is a TCA with prominent noradrenergic activity that has been noted to improve attention and concentration in children and adolescents with ADHD and TouretteŌĆÖs disorder plus ADHD. Symptom improvement is often significant with lower doses than needed for depression. Side effects are generally limited. The cardiac side effects of increased heart rate and elevation in blood pressure are usually not clinically significant; however, reports of sudden death in children and adolescents taking desipramine have resulted in marked reductions nationally in the use of desipramine in children and adolescents.

Nortriptyline

Given the concern about the cardiac effects of

desipramine, TCAs such as nortriptyline have been used for the treatment of

ADHD. The only available report, a chart review, assessed the effect of

nortriptyline in children and adolescents with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder plus ADHD.

The majority of subjects experienced mod-erate to marked improvement in both

ADHD and tics (Wilens et al., 1993).

Although the concern regarding sudden death is less with nortriptyline than with desipramine, it is prudent to obtain

baseline and follow-up electrocardiograms.

Clonidine and Guanfacine

Data supporting the efficacy of these agents has

been limited to open trial or small controlled trials. In the largest trial to

date subjects (N 5 34; mean

age of 10.4 years) were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of guanfacine or placebo.

Guanfacine was superior to placebo (37 versus 8%) in reduction of the total

score on the teacher-rated ADHD Rating Scale and significant differences were

also observed in omission and commission errors on a continuous performance

test (Scahill et al., 2001).

Selective Noradrenergic Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

One SNRI has recently been approved for the

treatment of ADHD in children and one is under FDA review for major depression.

Atomoxetine has been demonstrated to be effective and approved for use in

children and adults with ADHD. Given its mechanism of action it is possible

that atomoxetine could improve ADHD symptoms without exacerbating tic symptoms.

Studies are cur-rently underway. Similarly reboxetine, which has an indication

in Europe for depression, may be useful for ADHD in people with tics disorders.

Treatment of ObsessiveŌĆōCompulsive Disorder

Nonpharmacological Approaches

The positive role of cognitiveŌĆōbehavioral

treatments of OCD is well established in adults. Most reports of

nonpharmacological treatment of OCD in children and adolescents are case

studies. Only one report has a sufficient sample size and a protocol-driven,

cognitiveŌĆōbehavioral treatment regimen to begin to establish the possible role

of such treatment in children and adolescents with OCD. There are no specific

reports of cognitiveŌĆōbehavioral treatment or other nonpharmacological

treatments of OCD in adults or children with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder. Given the

success of cognitiveŌĆōbehavioral treatment in OCD, it is likely that patients

with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder and OCD will also be able to benefit from

cognitiveŌĆōbehavioral treatment.

Pharmacological Treatments

The number of agents available for the treatment of

OCD in pa-tients with and without TouretteŌĆÖs disorder is increasing. Cur-rently

available agents include the TCA clomipramine and the specific serotonin

reuptake inhibitors fluoxetine, sertraline, par-oxetine, fluvoxamine and

citalopram. Even though only a few of these agents have a specific indication

for OCD (clomipramine and fluvoxamine), others may be effective in OCD given

their serotoninergic activity. The choice of agent depends on the side-effect profile,

the potential drug interactions and the psychia-tristŌĆÖs familiarity with the

drug.

With the exception of clomipramine, all of the

available agents have mild and somewhat similar side-effect profiles. Drug

interaction issues must be taken into account, especially in chil-dren with

complex presentations or multiple medical conditions given the increased

possibility of multiple drug regimens. The re-ports of elevated TCA levels in

patients receiving TCA and fluox-etine are good examples of unforeseen drug

interactions with the specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Increasingly, augmentation strategies are pursued

in pa-tients with OCD and with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder plus OCD, when clinical

symptoms remain after initial treatment. A number of strategies have been used,

including augmentation with lithium, neuroleptics, buspirone, clonazepam,

liothyronine sodium (T3) and fenfluramine. Although positive outcomes of these

strate-gies have been reported in open trials, only neuroleptic aug-mentation

has shown to be of any benefit in controlled trials. Interestingly, controlled

trials of haloperidol combined with specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors in

patients with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder and OCD demonstrated improvement in both tic

and OCD symptoms.

Treatment-refractory Cases

Strategies for approaching two types of

treatment-refractory symptoms are discussed here: 1) patients who are truly

treatment-refractory with severe and impairing symptoms of TouretteŌĆÖs disorder

and OCD, despite conventional and heroic treatments, and 2) patients, often

children, who are clinically complex and enigmatic, and whose impairment is

disproportionally greater than their tic, obsessiveŌĆōcompulsive, or ADHD

symptoms would suggest.

Treatment-refractory Tics

Perhaps the most important ŌĆ£treatmentŌĆØ in patients

with severe incapacitating tics is a full clinical reevaluation to assess the

ad-equacy of previous evaluations and treatment efforts. It is not un-common

for treatment-refractory patients to have had inadequate evaluations and

treatment trials.

Two alternative treatment strategies are available

for truly treatment-refractory tics. When a single tic or a few tics are

re-fractory and impairing, the injection of botulinum toxin into the specific

muscle group can be helpful. This strategy is most useful for painful, dystonic

tics. Treatment has a long duration of action, but the effect does decrease in

2 to 4 months, and repeated injec-tions may be necessary. Specific side effects

are few, other than weakness in the affected muscle. Some patients reported the

loss of the premonitory sensation with their botulinum toxin treat-ment. For

the psychiatrist, it is essential to work with a neurolo-gist experienced in

using botulinum toxin.

There have been reports in the literature and the

media concerning the use of neurosurgical approaches for the treat-ment of

refractory tics. To date, the optimal size and location of the surgical

treatment lesions are not known. There are no well-controlled trials, although

some data are available from patients with OCD and tics who were treated for

OCD. In these patients, the impact on tic severity was mixed. Because these

approaches are particularly controversial, it is important, before considering

neurosurgical approaches, to complete a detailed and exhaustive reevaluation to

determine whether all other treatment options are exhausted. It is also

important that patients who pursue neuro-surgical approaches consider centers

of clinical excellence where controlled treatment trials are ongoing.

Treatment-refractory ObsessiveŌĆō Compulsive Disorder

A similarly thorough and exhaustive reevaluation is

critical for patients with TouretteŌĆÖs disorder plus OCD who present as

treat-ment-refractory. Diagnostic reevaluation focuses on whether other

psychiatric disorders are present and disabling and whether the current

hierarchy of clinical disability considers all conditions.

Pharmacological reevaluation is especially critical

be-cause there are an increasing number of new medications and potential

medication combinations. Rather than repeated change from one antiobsessional

agent to another, consideration can be given to augmentation strategies,

because they take less time than changing agents and may offer synergistic

benefits. Low-dose neuroleptic augmentation is the best first choice;

controlled trials support the use of low-dose neuroleptics for augmentation of

serotonin reuptake inhibitors in OCD. Lithium and T3 are proven, effective

augmenters of antidepressants for depression, yet neither is proven effective

in OCD. Because of the frequent overlap of OCD and major depression, lithium or

T3 augmenta-tion may be the next best choice.

Treatment-refractory or malignant OCD has been the

psy-chiatric disorder most frequently treated with neurosurgical in-terventions

in the modern era. Whereas it is a major treatment in-tervention, the surgical

approaches are somewhat better defined, and the outcome in severe cases is

often positive. Also, medical centers are available that specialize in the

presurgical work-up and the neurosurgical procedure.

Clinically Complex Patients

Clinically complex patients may be severely

impaired without having severe tic or OCD symptoms. The clinically complex

patient is often a diagnostic dilemma with additional diagnoses complicating

the clinical picture. In addition, patients can be-come clinically complex when

otherwise straightforward treat-ments are a challenge to implement.

Diagnosis

In clinically complex patients, the diagnostic

challenge is not an accurate assessment of tics, ADHD, obsessiveŌĆōcompulsive

symptoms, or LDs, although this is important. In clinically com-plex patients,

the diagnostic goal is to identify what other condi-tions or factors may be

present that make the current treatment approaches difficult.

From a strictly diagnostic point of view, it is the

additional psychiatric conditions beyond TouretteŌĆÖs disorder, OCD, ADHD and LDs

that often escape clinical observation and result in diag-nostic dilemmas and

treatment failures.

Treatment Implementation

Clinical problems occur when the treating

psychiatrist does not have access to critical information or is not in control

of the treat-ment process. Traditionally, psychiatrists develop a relationship

with the patient and the other major figures in the patientŌĆÖs life. Given the

current clinical climate, a comprehensive level of in-volvement can be

overwhelming and enormously time-consum-ing for the psychiatrist. Because it is

increasingly difficult for the psychiatrist to be as involved as necessary,

problems with poorly coordinated team efforts and the psychiatristŌĆÖs lack of

awareness of important clinical issues can have a negative impact on the

treatment of a patient.

Psychiatrists who work with children and

adolescents may wish to consider changes in their treatment approaches to these

patients. Experience in tertiary care centers suggests that expanded time with

the parents is a critically important and ef-ficient approach to care.

Psychiatrists who form a treatment part-nership with families, respecting and

addressing their concerns, educating them about TouretteŌĆÖs disorder, training

them to evalu-ate and manage complex behaviors, and empowering them to be an

effective advocate for their child, are providing good care. In working

directly with families, the collection of important infor-mation regarding the

familyŌĆÖs and patientŌĆÖs functioning is direct and regular, and often small

interventions can produce changes in family functioning that have a positive

ripple effect throughout the life of the child.

Pharmacological Treatment Dilemmas

It is often difficult to obtain accurate

information regarding side effects and treatment response in child patients.

Parents, children and psychiatrists, in spite of a good collaborative effort,

may have different understandings of the target symptoms, side-effect pro-file,

and what constitutes a positive clinical response. This ambi-guity makes any

but the most robust clinical responses difficult to observe. Again, experience

at tertiary referral centers suggests that the lack of a clinical response to

medication in complex pa-tients may often be related to inadequate monitoring

of medicine effects and inadequate treatment trials.

Clinically complex patients may not have a robust

re-sponse to a single medication but may require multiple medica-tion trials to

identify which medications offer the most benefit, and in which combination.

Sequential treatment trials are dif-ficult for all involved, especially

children and families, who are often looking for a single powerful intervention.

With the added complexity of treatment, there is the added risk of confusion

and the need for an excellent psychiatristŌĆōpatientŌĆōfamily relation-ship. In

those cases in which the relationship is not optimal, it is possible that a

patient may not have the maximal clinical benefit of pharmacological

interventions.

With increasing numbers of available psychotropic

medi-cations, psychiatrists become increasingly less experienced with the range

of clinical effects and side effects in individual medica-tions. In clinically

complex patients, the prescription of unfamil-iar medications may be necessary

but may add to the risk that a trial will be discontinued prematurely because

of doubt about a side effect. In addition, unusual side effects, such as the apathy

or disinhibition syndromes seen with some patients receiving the specific

serotonin reuptake inhibitors, may go unnoticed and add to clinical morbidity.

Whereas pharmacological interventions offer great

prom-ise, clinical experience suggests that excellent diagnostic skills, good

relationships with the patient and family, time, and a keen eye for effects and

side effects are necessary for benefits to be realized. Less intensive efforts

may make patients appear more complex than necessary.

Related Topics