Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Tic Disorders

Tic Disorders: Standard Approaches to Treatment

Standard Approaches to Treatment

Educate the Patient and Family

The initiation of treatment can be a delicate

process, given the difficulties patients and their families experience before

finding appropriate care. Most families are frightened about their child’s

having a neuropsychiatric disorder and envision a grim progno-sis. After the

evaluation is completed, often in the first session, general education of the

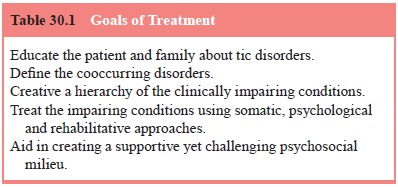

patient and family about the course of the tic disorder is essential (Table

30.1). Most patients and fami-lies are relieved to hear that the majority of

persons with tics have consistent improvement in tic severity as they move

through their teenage years and into adulthood. They are also pleased to hear

that tic symptoms are not inherently impairing.

Identify Cooccurring Disorders

Identifying whether ADHD, LD and OCD are present is

espe-cially important because they are often the more common im-pairing

conditions in these children. One of the major pitfalls of treatment of

patients with Tourette’s disorder is to pursue tic sup-pression to the

exclusion of the treatment of other cooccurring conditions that are present and

possibly more impairing.

Create a Hierarchy of the Clinically Impairing Conditions

Most psychiatrists, as part of their formulation,

create some clini-cal hierarchy; yet in Tourette’s disorder, with the multitude

of often complex problems, it is essential that a conscious effort be made to

formulate, organize and create hierarchies for treatment. For example children

with moderate tics and separation anxiety with school refusal should be

considered for a treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)

for their separation anxiety rather than neuroleptics for tic suppression (The

Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group, 2001). It is

possible with successful treatment of the anxiety disorder that patient may

also experience a reduction in tic severity also.

Treat the Impairing Conditions

Tic Suppression: Pharmacological

The goal of pharmacological treatment is the

reduction of tic severity, not necessarily the elimination of tics. Haloperidol

has been used effectively to suppress motor and phonic tics for more than 30

years. Since that time, a number of other neuroleptic agents have also been

identified as useful in tic suppression, in-cluding fluphenazine and pimozide.

In Europe, the substituted benzamides, sulpiride and tiapride, and the

nonneuroleptic tetrabenazine have also been shown to be useful. As new

neu-roleptic agents become available, clinical trials for tic suppres-sion

invariably occur. Preliminary results with risperidone have been mixed, whereas

trials with clozapine are more uniformly negative. The major drawback with

neuroleptic agents is the fre-quent and significant side effects, which often

preclude continued use of the medication.

Haloperidol

Haloperidol is a high-potency neuroleptic that

preferentially blocks dopamine D2 receptors. Historically,

haloperidol has been the most frequently used medication for tic suppression.

It is ef-fective in a clear majority of patients, although relatively few

pa-tients are willing to tolerate the side effects to obtain the

tic-sup-pressing benefits. Neuroleptics are often effective at low doses, and

low doses minimize side effects. For haloperidol, doses in the range of 0.5 to

2.0 mg/day are usually adequate. Starting dosages are low (0.25–0.5 mg/day),

with small increases in dose (0.25–0.5 mg/day) every 5 to 7 days. Most often

the medication is given at bedtime, but with low doses, some patients may

require twice-a-day dosing for good tic control.

Side effects with all neuroleptics are common and

include sedation, acute dystonic reactions, extrapyramidal symptoms including

akathisia, weight gain, cognitive dulling and the com-mon anticholinergic side

effects. There have also been reports of subtle, difficult to recognize side

effects with neuroleptics, in-cluding clinical depression, separation anxiety,

panic attacks and school avoidance.

Dosage reduction is the most prudent response to

side ef-fects, although the addition of medications such as benztropine for the

extrapyramidal symptoms can be useful. Dosage reduc-tion in those children with

Tourette’s disorder who have been administered neuroleptics long term may be

complicated by withdrawal dyskinesias and significant tic worsening or rebound.

Withdrawal dyskinesias are choreoathetoid movements of the orofacial region,

trunk and extremities that appear after neu-roleptic discontinuation or dosage

reduction and tend to resolve in 1 to 3 months. Tic worsening even above

pretreatment baseline level (i.e., rebound) can last up to 1 to 3 months after

discontinu-ation or dosage reduction. Tardive dyskinesia, which is similar in

character to withdrawal dyskinesia, most often develops during the course of

treatment or is “unmasked” with dosage reductions. Rarely have cases of tardive

dyskinesia been reported to occur in patients with Tourette’s disorder.

Fluphenazine

Whereas fluphenazine has never undergone controlled

trials, clinical experience suggests that it has somewhat fewer side effects

than haloperidol. Fluphenazine has both dopamine D1 and D2

receptor-blocking activity, and the side effect profile is similar to that of

haloperidol. Fluphenazine is slightly less potent than haloperidol so that

starting doses are somewhat higher (0.5–1 mg/day), as are treatment doses (3–5

mg/day).

Pimozide

Pimozide is a potent and specific blocker of

dopamine D2 recep-tors. Its side-effect profile is generally similar

to that of the other neuroleptics, although it has fewer sedative and

extrapyramidal side effects than haloperidol. In contrast to either haloperidol

or fluphenazine, pimozide has calcium channel blocking properties that affect

cardiac conduction, as evidenced by changes in the electrocardiogram. The

coadministration of other medications that affect cardiac conduction, such as

the tricyclic antidepres-sants (TCAs), is generally contraindicated. Baseline

and follow-up electrocardiograms are important for adequate management of

patients.

Beginning treatment with a dose of 1 mg/day is

prudent, although with pimozide’s long half-life, every-other-day dos-ing can

be used to decrease the effective daily dose. Increases of up to 1 mg/day can

occur every 5 to 7 days until symptoms are controlled. Most patients experience

clinical benefit with few side effects with doses of 1 to 4 mg/day. Higher doses

can be associated with more side effects. In a comparison of pimozide,

haloperidol and no drug in patients with Tourette’s disorder and ADHD, pimozide

at 1 to 4 mg/day was useful in decreasing tics and improving some aspects of

cognition that are commonly im-paired in ADHD (Sallee and Rock 1994). The

potential to have impact on both Tourette’s disorder and ADHD symptoms with a

single drug is a clear advantage that pimozide may have over other

neuroleptics.

Atypical Neuroleptics

The atypical neuroleptics appear to have replaced

the standard neuroleptics as the mainstay of treatment for the psychotic

dis-orders. Given the potentially lower risk for tardive dyskinesia with these

agents, their efficacy has been assessed for tic sup-pression in patients with Tourette’s

disorder. To date there are only small controlled or open trials to guide the

clinician in the use of these agents. Clozapine does not appear to be effective

as a tic-suppressing agent and its hematological side effects preclude its use.

Risperidone has been effective in reducing tic symptoms severity in one

controlled trial (Dion et al., 2002)

and may have the added benefit of augmenting SSRIs in treating tic-related OCD.

Olanzapine in low doses does not appear to have the

same tic-suppressing power as the typical neuroleptics which may be related to

olanzapine’s relatively weak dopamine D2 blocking activity. Side

effects, especially weight gain, have dampened the enthusiasm for the atypicals

risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine. In one of the larger placebo-controlled

trials (N 5 56) of

the new neuroleptics, ziprasidone was found to be effective in reducing tic

symptoms. The mean dose was low 28 ± 10

mg/day. There were few side effects including a low incidence of weight gain

(Gilbert et al., 2000).

Clonidine and Guanfacine

Whereas controlled trials have shown that some

patients ben-efit with symptom reduction, the overall effect of clonidine for

tic suppression and ADHD is more modest than that achieved with the “gold

standards” (haloperidol and the stimulants, re-spectively) for these conditions

(Goetz, 1993). Given clonidine’s mild side-effect profile, it is often the

first drug used for tic suppression, especially in those children with

Tourette’s disor-der and ADHD. Treatment is initiated at 0.025 mg/day and

in-creased in increments of 0.025 to 0.05 mg/day every 3 to 5 days or as side

effects (sedation) allow. Usual effective treatment doses are in the range of

0.1 to 0.3 mg/day and are given in di-vided doses (4–6 hours apart). Higher doses

are associated with side effects, primarily sedation, and are not necessarily

more effective. The onset of action is slower for tic suppression (3–6 weeks)

than for ADHD symptoms. Side effects, in addition tosedation, include

irritability, headaches, decreased salivation, and hypotension and dizziness at

higher doses. Interestingly, owing to clonidine’s short half-life, some

patients experience mild withdrawal symptoms between doses. More severe

re-bound in autonomic activity and tics can occur if the medica-tion is

discontinued abruptly. Some patients find that clonidine in the transdermal

patch form provides a more stable clinical effect and avoids multiple doses

each day. Children are usually stabilized on oral doses before they are

switched to the patch. A rash at the site of the patch is a common, but

manageable, complication of treatment.

Guanfacine is an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist that

poten-tially offers greater benefit than clonidine because of differ-ences in

site of action, side effects and duration of action. In nonhuman primates,

guanfacine appears to bind preferentially with alpha-2-adrenergic receptors in

prefrontal cortical re-gions associated with attentional and organizational

functions. Guanfacine’s long half-life offers the advantage of twice-a-day

dosing, which is more convenient than the multiple dosing required with

clonidine. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (N 5 31) of children with tics and ADHD, guanfacine in

doses up to 0.3 mg/day had an average 31% reduction in tic severity compared

with no reduction on placebo. Clinically the effect on tics is less than would

be expected on neuroleptics (Scahill et

al., 2001).

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines can be useful in decreasing

comorbid anxiety in patients with Tourette’s disorder. In addition, clonazepam

ap-pears also to be useful in selected patients for tic reduction. Of-ten,

doses of 3 to 6 mg/day may be necessary for tic reduction. Because sedation is

a significant side effect at these dosages, an extended titration phase of 3 to

6 months may be necessary. Simi-larly, a slow taper is required to avoid

withdrawal symptoms.

Pergolide

Agonist activity on presynaptic dopamine neurons

results in decrease dopamine release and may therefore result in decreased tic

severity in people with Tourette’s disorder. To exploit this finding a number

of small open trials of dopamine agonists and a small controlled trial of

pergolide (N 5 24) have

been conducted. Pergolide, a mixed D1–D2–D3

dopamine agonist often used for restless leg syndrome, was found to be superior

to placebo in reducing tic severity and was associated with few adverse events

(Gilbert et al., 2000). Doses used

were low as higher doses may be associated with dopamine agonist effects

postsynaptically.

Baclofen

Baclofen, a muscle relaxant, is GABA-B receptor

agonist that acts presynaptically to inhibit the release of excitatory amino

acids such as glutamate. In a small placebo controlled crossover trial (N 5 10) baclofen 20 mg t.i.d. was

not found to be effective in reducing tic severity but did appear to have an

effect on tic-related impairment (Singer et

al., 2001).

Infection and Autoimmune-based Treatments

Several treatment studies have been undertaken

based on the hy-pothesis that some forms of Tourette’s disorder or OCD may be

related to streptococcal infection. Based on the beneficial effects of

penicillin prophylaxis in preventing recurrences of rheumatic fever, a similar

strategy was employed in subjects meeting cri-teria for PANDAS (Garvey et al., 1999). The study was limited by

a number of flaws and although the concept of prophylaxis is compelling,

special design considerations will be required in future studies.

After small open trials with the immunomodulatory

treat-ments such as plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), a

larger trial comparing these methods to sham IVIG was undertaken. Children

meeting criteria for PANDAS (N 5 30) were

randomly assigned (1 : 1 : 1) to treatment with plasma exchange (five

single-volume exchanges over 2 weeks), IVIG (1 g/kg daily on two consecutive

days), or placebo (saline solution given in the same manner as IVIG) and

subjects were reported as doing well at 1 year (Lougee et al., 2000). Although this study is encour-aging there are a

number of methodological problems including lack of a placebo control for

plasma exchange and inclusion of uncontrolled subjects in outcome analysis

after the first month. These findings do support ongoing investigation of these

treat-ment methods but given the cost, risk and highly experimental nature of

these treatments it is recommended that patients obtain these treatments only

in the context of ongoing clinical inves-tigations of these treatments at major

medical research centers (for further information, see http://intramural.nimh.nih.gov/re-search/pdn/web.htm).

Tic Suppression: Nonpharmacological

The behavioral technique shown to be most effective

is habit reversal training. For Tourette’s disorder, habit reversal training is

the use of a competing muscle contraction or behavioral re-sponse that opposes

the tic movement. This method is usually combined with relaxation training,

self-monitoring, awareness training and positive reinforcement. In the few

published studies of habit reversal training, there were marked overall

reductions in tic frequency. Treatment averaged 20 training sessions during an

8- to 11-month period. Marked tic reduction was noted at 3 to 4 months.

Interestingly, urges or sensations experienced before the tic movements also

decreased with behavioral treatment (Azrin and Peterson, 1990).

Psychosocial Treatments

There are no published systematic studies of

psychosocial in-terventions for patients with Tourette’s disorder. Most

treatment efforts are based on a combination of traditional psychosocial in-terventions

and clinical judgment.

Education

Perhaps the most useful psychosocial and

educational interven-tion is to make the patient aware of the Tourette Syndrome

Asso-ciation, both national and local c-hapters. This and other self-help

groups can be useful as a source of support and education for patients,

families and psychiatrists.

Therapy

Individual psychotherapy can be useful for support,

develop-ment of awareness, or addressing personal and interpersonal problems

more effectively. Family therapy can be useful when families have problems

adjusting, functioning and communicat-ing. Although most families do well, some

families have difficul-ties understanding the involuntary nature of tics and

may punish their children for their tics, even after diagnosis and education.

Alternatively, some families have more behavior difficulties with their

children after diagnosis than before. Many parents of chil-dren with Tourette’s

disorder inadvertently lower general behav-ior expectations because of confusion

about what behaviors areand are not tics, or because of the parents’ desire not

to add any additional stress to the youngster’s life. Also, with confusion in

the field regarding the scope of problems in Tourette’s disorder, some parents

see all maladaptive behaviors as involuntary and do not hold their children

responsible for their behaviors. For chil-dren with Tourette’s disorder to do

well, they need support from their family to develop effective self-control in

areas not affected by Tourette’s disorder so that optimal adaptation can occur.

In newly diagnosed adults, psychotherapy oriented

toward adequate adjustment to the diagnosis is important but not always easy.

Adult patients frequently experience a mixture of relief to be finally

diagnosed, with anger and resentment related to their past experiences with

discrimination or inadequate medical care. Severely affected adults may also

need psychotherapy to deal with the psychological and psychosocial difficulties

related to having a chronic illness.

Other Psychosocial Interventions

For children, active intervention at school is

essential to create a supportive yet challenging academic and social

environment. Ef-forts to educate teachers, principals and other students can

result in increased awareness of Tourette’s disorder and tolerance for the

child’s symptoms.

Many young adults are finding Tourette’s disorder

support and social groups important for interpersonal contact and con-tinued

adult development. Efforts to keep people with Tourette’s disorder working are

important, as are rehabilitation efforts for those who are not working. Finding

housing and obtaining disa-bility or public assistance may be necessary for the

most disabled patients with Tourette’s disorder.

Genetic Counseling

One question commonly asked by young adults with

Tourette’s disorder is their risk for having a child with Tourette’s disorder.

Given the fact that many who present for clinical attention with Tourette’s

disorder have comorbid conditions, genetic counseling of people with Tourette’s

syndrome should include not only the risk for Tourette’s disorder but also the

risk for other neuropsy-chiatric problems such as ADHD or OCD that may be part

of the young person’s history. In addition, because the base rate of

neu-ropsychiatric disorders is high, it is not uncommon for spouses of people

with Tourette’s disorder to have a neuropsychiatric disorder. In providing

counseling to these couples it is impor-tant that genetic counseling be

conducted not just about Tourette syndrome, but about the other conditions that

occur as part of the young couple’s history.

Related Topics