Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Elimination Disorders and Childhood Anxiety Disorders

Enuresis

Enuresis

Definition

Functional enuresis is usually defined as the

intentional or involun-tary passage of urine into bed or clothes in the absence

of any iden-tified physical abnormality in children older than 4 years of age.

It is often associated with psychiatric disorder and enuretic children are

frequently referred to mental health services for treatment.

Course and Natural History

The acquisition of urinary continence at night is

the end stage of a fairly consistent developmental sequence. Bowel control

dur-ing sleep marks the beginning of this process and is followed by bowel

control during waking hours, bladder control during the day, and finally

night-time bladder control. Most children achieve this final stage by the age

of 36 months. With increasing age, the likelihood of spontaneous recovery from

enuresis decreases. The chronic nature of the condition is further shown in the

study by Rutter and colleagues (1973), in which only 1.5% of 5-year-old

bed-wetters became dry during the next 2 years.

Enuresis (Not Due to a Medical Condition)

This

disorder is characterized by the repeated voiding of urine into clothes or bed

at the age of 5 (chronicalogically or devel-opmentally) or older for a period

of at least twice weekly over three months. Enuresis reflects a significant

emotional distress or impairment in social, academic or other important ares of

functioning. Enuresis may be either diurnal (during waking

hours) or nocturnal (during

night-time sleep) or a combination of both.

Nocturnal enuresis is as common in boys as girls

until the age of 5 years, but by age 11 years, boys outnumber girls 2 : 1. Not

until the age of 8 years do boys achieve the same levels of night-time

continence that are seen in girls by the age of 5 years, probably due to slower

physiological maturation in boys. In addition, the increased incidence of

secondary enuresis (occurring after an initial 1-year period of acquired

continence) in boys further affects the sex ratio seen in later childhood.

Daytime enuresis occurs more commonly in girls and is associated with higher

rates of psychiatric disturbance.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Possible biological factors include a structural

pathological con-dition or infection of the urinary tract (or both), low

functional bladder capacity, abnormal antidiuretic hormone secretion, ab-normal

depth of sleep, genetic predisposition and developmenta delay. Evidence has

also been found for sympathetic hyperactivity and delayed organ maturation as

seen by delay in ossification.

Obstructive lesions of the urinary outflow tract,

which can cause urinary tract infection (UTI) as well as enuresis, have been

thought to be important, with a high prevalence of such abnormalities seen in

enuretic children referred to urologic clinics. This degree of association is not

seen at less specialized pediatric centers, however, and most studies linking

urinary outflow obstruction to enuresis are methodologically flawed (Shaffer et al., 1979). Structural causes for

enuresis should be considered the exception rather than the rule.

UTI has been found to occur frequently in children,

es-pecially girls and a large proportion (85%) of them have been shown to have

nocturnal enuresis. Also, in 10% of bedwetting girls, urinalysis results show

evidence of bacterial infection. The consensus is that as treating the

infection rarely stops the bedwet-ting, UTI is probably a result rather than a

cause of enuresis.

The concept that children with enuresis have low

functional bladder capacities has been widely promoted. Shaffer and colleagues (1984)

found a functional bladder capacity one standard deviation lower than expected

in 55% of a sample of enuretic children in school clinics. Although low

functional capacity may predispose the child to enuresis, successful behavioral

treatment does not appear to increase that capacity, rather the sensation of a

full (small) bladder promotes waking to pass urine so that enuresis does not

occur. Re-duction of nocturnal secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) has been

described in a small number of children with enuresis, causing excessive

amounts of dilute urine to be produced during the night and overwhelming

bladder capacity. Several mechanisms are asso-ciated with enuresis, including

increased nocturnal urine volume, small nocturnal functional bladder capacity,

increased spontane-ous bladder contractions, and the inability to arouse to the

stimulus of a large and/or contracting bladder. This may identify two main

groups of children with enuresis: those who demonstrate nocturnal spontaneous

bladder contractions (detrusor dependent enuresis) and those with nocturnal

polyuria (volume dependent enuresis).

Approximately 70% of children with nocturnal

enuresis have a first-degree relative who also has or has had nocturnal

enuresis. Twin studies have shown greater monozygotic (68%) than dizygotic

(36%) concordance. An association between enu-resis and early delays in motor,

language and social development has been noted in both prospective community

samples and a large retrospective study of clinical subjects (Steinhausen and

Gobel, 1989). Genetic factors are probably the most important in the etiology

of nocturnal enuresis but somatic and psychosocial environmental factors have a

major modulatory effect. Most com-monly, nocturnal enuresis is inherited via an

autosomal dominant mode of transmission with high penetrance (90%). However, a

third of all cases are sporadic. Four gene loci associated with noc-turnal

enuresis have been identified but the existence of others is presumed (locus

heterogeneity). Other psychosocial correlates described include delayed toilet

training, low socioeconomic class, stress events and other child psychiatric

disorders. Stress events seem to be more clearly associated with secondary

enu-resis. Reported events include the birth of a younger, early

hospi-talizations and head injury (Chadwick, 1985).

Psychiatric disorder occurs more frequently in

enuretic children than in other children, although no specific types have been

identified (Mikkelsen and Rapoport, 1980). The relative fre-quency of disorder

ranges from two to six times that in the gen-eral population and is more

frequent in girls, in children who also have diurnal enuresis and in children

with secondary enuresis.

There is little evidence that enuresis is a symptom

of underlying disorder because psychotherapy is ineffective in reducing

enuresis, anxiolytic drugs have no antienuretic effect, tricyclic

antidepressants exert their therapeutic effect independent of the child’s mood,

and purely symptomatic therapies, such as the bell and pad, are equally

effective in disturbed and nondisturbed children. A further explanation for the

association is that enuresis, a distressing and stigmatizing affliction, may

cause the psychiatric disorder. However, although some studies have shown that

enuretic children who undergo treatment become happier and have greater

self-esteem, other studies show that psychiatric symptoms do not appear to

lessen in children who are successful with a night alarm. A final possibility

is that enuresis and psychiatric disorder are both the result of joint

etiological factors such as low socioeconomic status, institutional care, large

sibships, parental delinquency, and early and repeated disruptions of maternal

care. Shared biological factors may also be important in that delayed motor,

speech and pubertal development, already shown to be associated with enuresis,

have proven to be more frequent in disturbed enuretic children than in those

without psychiatric disorder.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

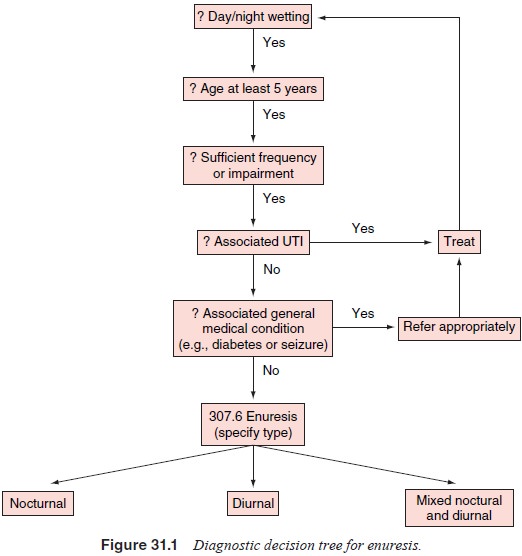

The presence or absence of conditions often seen in

association with enuresis should be assessed and ruled out as appropriate

(Figure 31.1). Other causes of nocturnal incontinence should be excluded, for

example, those leading to polyuria (diabetes mel-litus, renal disease, diabetes

insipidus) and, rarely, nocturnal epilepsy.

Assessment

History

Information on the frequency, periodicity and duration of symp-toms is needed to make the diagnosis and distinguish functional enuresis from sporadic seizure-associated enuresis. If there is diurnal enuresis, an additional treatment plan is required. A fam-ily history of enuresis increases the likelihood of a diagnosis of functional enuresis and may explain a later age at which chil-dren are presented for treatment. Projective identification by the affected parent–whereby the parent does not separate feelings about himself having the diagnosis and the current experience of the affected child–may further hinder treatment. For subjects with secondary enuresis, precipitating factors should be elicited, although such efforts often represent an attempt to assign mean-ing after the event.

Questions that are useful in obtaining information

for treat-ment planning include “Why is this a problem?” and “Why does this

need treatment now?” because these factors may influence the choice of

treatment (is a rapid effect needed?) or point to other pressures or

restrictions on therapy. It is important to inquire about previous management

strategies used at home, for example, fluid restriction, nightlifting (getting

the child out of bed to take to the toilet in an often semi-asleep state),

rewards and punish-ments. Parents often come with the assertion that they have

tried everything and that nothing has helped. Examining the reasons for failure

of simple strategies is useful for ensuring that more sophisticated treatments

do not befall the same fate. There is little evidence that fluid restriction is

useful, although nightlifting may be beneficial for the large number of

children who never reach professional attention. Rewards are usually material

and are given only for unreasonably high performance levels, with the delay

be-tween action and reward being too long. Physical punishment and verbal

chastisements, ineffective at best, may well maintain the enuresis. Punishment

is often too harsh and tends to be applied inconsistently depending on parental

mood. If specific treatments have been prescribed, either behavioral or

pharmacological, it is important to discover the reasons they may have failed.

Mental Status Examination

The child’s views and any misconceptions that he or

she may have about the enuresis, its causes and its treatment should be fully

explored. Asking the child for three wishes may help determine whether the

enuresis is a concern to the child. This may unmask marked embarrassment or

guilt from behind a facade of denial about the problem and can be educational

for parents who believe their children could stop wetting “if only they wanted

to or tried harder”. Pictures drawn by the child that describe how the child

views himself or herself when enuresis is a problem and when it is not appropriate

for younger children and can graphically illus-trate the misery experienced by

children with enuresis.

Physical Examination

All children should have a routine physical

examination, with par-ticular emphasis placed on detection of congenital

malformations indicative of urogenital abnormalities. A midstream specimen of

urine should be examined for the presence of infection. Radio-logical or

further medical investigation is indicated only in the presence of infected

urine, enuresis with symptoms suggestive of recurrent UTI (frequency, urgency

and dysuria), or polyuria.

Treatment

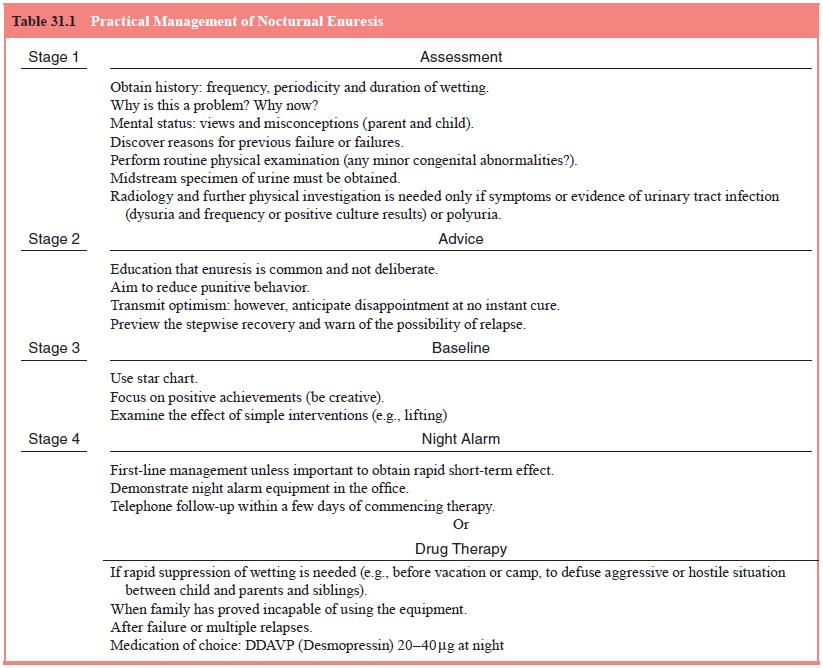

Practical management for nocturnal enuresis is

presented in Table 31.1.

The overall goals of treatment can depend on the

reason for referral. Commonly, the child is brought to the physician before

some planned activity, for example, a family vacation or a trip to camp, and

the need is for a rapid (e.g., pharmacological) short-term therapy. A gradual

behavioral approach would not likely meet with much approval even though it may

offer a chance for a permanent cessation of wetting.

Standard Treatment

About 10% of children have a reduction in the

number of wet nights after a single visit to a clinician in which the only

interven-tion was the recording of baseline wetting frequency and simple

reassurance. Such reassurance should make clear that enuresis is a biological

condition that is made worse by stress and that may be associated in a

noncausal way with other psychiatric disor-ders. Younger children can be told

that their problem is shared by many others of the same age. The excellent

prognosis for patients who comply with therapy should be stressed. Recording

the fre-quency of enuresis can be achieved by using a simple star chart. This

is most effective if performed by the child, who records each dry night with a

star. The completed chart is then shown to the parents on a daily basis, and

they can provide appropriate praise and reinforcement.

Waking and Fluid Restriction

Although systematic studies have failed to show any

effect of these interventions with enuretic inpatients, it may be that these

strategies work for the majority of enuretic children who are not referred for

treatment.

Surgery

Based on the premise that enuresis is causally

associated with outflow tract obstruction, various surgical procedures have

been advocated, for example, urethral dilatation, meatotomy, cystoplasty and

bladder neck repair. This cannot be supported because, in addition to the

dubious concept of outflow tract ob-struction per se, the surgery does not

alter the urodynamics of the bladder. Reported positive treatment effects are

slight (no controlled studies exist), and there remains a significant

poten-tial for adverse effects (urinary incontinence, epididymitis and aspermia).

Pharmacotherapy

Although it has been repeatedly demonstrated that

temporary suppression rather than cure of enuresis is the usual outcome of drug

therapy, it remains the most widely prescribed treatment in the USA. Four

classes of drugs have principally been employed: synthetic antidiuretic

hormones, tricyclic antidepressants, stimu-lants and anticholinergic agents.

Synthetic

Antidiuretic Hormone A number of randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials (RCT) have shown that the

synthetic vasopeptide DDAVP (desmopressin) is effective in enuresis. The drug

is usually administered intranasally, although oral preparations of equal

efficacy have been developed (equiva-lent oral dose is 10 times the intranasal

dose). Almost 50% of children are able to stop wetting completely with a single

nightly dose of 20 to 40 μg of

DDAVP given intranasally. A further 40% are afforded a significant reduction in

the frequency of enuresis with this treatment. As with tricyclic

antidepressants, however, when treatment is stopped, the vast majority of

individuals re-lapse. Side effects of this medication include nasal pain and

con gestion, headache, nausea and abdominal pain. Serious problems of water

intoxication, hyponatremia and seizures are rare. It is important to be aware

that intranasal absorption is reduced when the patient has a cold or allergic

rhinitis. The mode of action of desmopressin is unknown. It may reduce the

production of night-time urine to an amount less than the (low) functional

volume of the enuretic bladder, thereby eliminating the urge to mictur-ate.

With regard to identifying those most likely to respond to DDAVP treatment, it

has been found that those most likely to be permanently dry are infrequent

wetting older children who respond to lower dose (20 μg) desmopressin.

Tricyclic

Antidepressants The short-term effectiveness of imipramine and other related antidepressants has also been

demonstrated via many RCTs. Imipramine reduces the fre-quency of enuresis in

about 85% of bed-wetters and eliminates enuresis in about 30% of these

individuals. Night-time doses of 1 to 2.5 mg/kg are usually effective and a

therapeutic ef-fect is usually evident in the first week of treatment. Relapse

after withdrawal of medication is almost inevitable, so that 3 months after the

cessation of tricyclic antidepressants, nearly all patients will again have

enuresis at pretreatment levels. Side effects are common and include dry mouth,

dizziness, postural hypotension, headache and constipation. Toxicity after

acci-dental ingestion or overdose is a serious consideration, caus-ing cardiac

effects, including arrhythmias and conduction de-fects, convulsions,

hallucinations and ataxia. Concern has been expressed about the possibility of

sudden death (presumably caused by arrhythmia) in children taking tricyclic

drugs. The mode of action for tricyclic antidepressants is unclear, although

one observation is that tricyclic agents seem to increase func-tional bladder

volumes possibly resulting from noradrenergic reuptake inhibition.

Stimulant

Medication Sympathomimetic stimulants such as dexamphetamine have been used to

reduce the depth of sleep in children with enuresis; but because there is no

evidence that enu-resis is related to abnormally deep sleep, their lack of

effective-ness in stopping bed-wetting is no surprise. Used in combination with

behavioral therapy, there is some evidence that stimulants can accentuate the

learning of nocturnal continence.

Anticholinergic

Drugs Drugs such as propantheline, oxybu-tynin and terodiline can reduce the

frequency of voiding in indi-viduals with neurogenic bladders, reduce urgency

and increase functional bladder capacity. There is no evidence, however, that

these anticholinergic drugs are effective in bed-wetting, although they may

have a role in diurnal enuresis. Side effects are fre-quent and include dry

mouth, blurred vision, headache, nausea and constipation.

Psychosocial Treatments

The night alarm was first used in children with

enuresis in the 1930s. This system used two electrodes separated by a device

(e.g., bedding) connected to an alarm. When the child wet the bed, the urine

completed the electrical circuit, sounded the alarm and the child awoke. All

current night alarm systems are merely refinements on this original design. A

vibrating pad beneath the pillow can be used instead of a bell or buzzer, or

the electrodes can be incorporated into a single unit or can be mini-aturized

so that they can be attached to night (or day) clothing. With treatment, full

cessation of enuresis can be expected in 80% of cases. Reported cure rates

(defined as a minimum of 14 consecutive dry nights) have ranged from 50 to

100%. The main problem with this form of enuretic treatment, however, is that

cure is usually achieved only within the second month of treatment. This factor

may influence clinicians to prescribe pharmacological treatments that, although

more immediately gratifying, do not offer any real prospect of cure. It has

been suggested that adjuvant therapy with methamphetamine or desmopressin will

reduce the amount of time before continence is achieved. Using a louder

auditory stimulus or using the body-worn alarm may also improve the speed of

treatment response. Factors associated with delayed acquisition of continence

in-clude failure of the child to wake with the alarm, maternal anxi-ety and a

disturbed home environment, although no influence has been seen regarding the

age of the child or the initial wet-ting frequency.

A further consequence of the delayed response to a

night alarm is premature termination occurring in as many as 48% of cases and

is more common in families that have made little pre-vious effort to treat the

problem, in families that are negative or intolerant of bed-wetting, and in

children who have other behav-ioral problems. Compliance-reducing factors also

include failure to understand or follow the instructions, failure of the child

to awaken, and frequent false alarms. The only reported side effect of

treatment with the night alarm is “buzzer ulcers” caused by the child lying in

a pool of ionized urine. This problem has been eliminated with modern

transistorized alarms that do not employ a continuous, relatively high voltage

across the electrodes to de-tect enuresis.

Relapse after successful treatment, if it occurs,

will usually take place within the first 6 months after cessation of treatment.

It is reported that approximately one-third of chil-dren relapse; however, no

clear predictors of relapse have been identified.

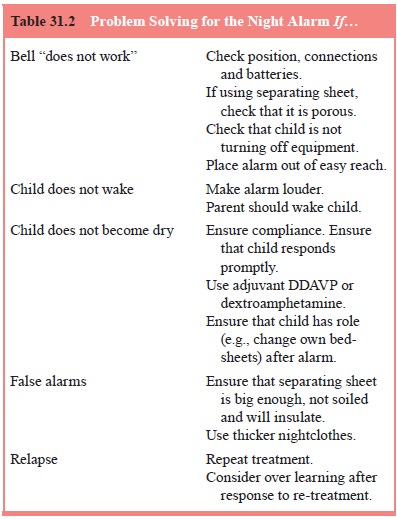

Table 31.2 presents various remedies for night

alarm problems.

Ultrasonic Bladder Volume Alarm

Although the traditional enuresis alarm has good

potential for a permanent cure, the child is mostly wet during treatment.

Fur-thermore, the moisture alarm requires that the child make the somewhat

remote association between the alarm event and a full bladder after the bladder

has emptied. In an exploratory study (Pretlow,

1999), a new approach to treating nocturnal enuresis was investigated

using a miniature bladder volume measurement instrument during sleep. In this,

an alarm sounded when bladder volume reached 80% of the typical enuretic

volume. Two groups were studied. Group 1 used the night-time device alone;

group 2, in addition, had supplementary daytime bladder retention train-ing

(aiming to increase functional capacity). In groups 1 and 2 the mean dryness

rate before study initiation versus during the study was 32.9 and 9.3% versus

88.7 and 82.1%, respectively. Night-time bladder capacity increased 69% in

group 1 and 78% in group 2, while the cure rate was 55% (mean treatment pe-riod

10.5 months) and 60% (mean treatment period 7.2 months), respectively.

Acupuncture

The efficacy of traditional Chinese acupuncture has

been studied (Serel et al., 2001) in

a small (n 5 50)

clinical sample. It was reported that within 6 months, 86% of patients were

completely dry and a further 10% of patients were dry on at least 80% of

nights. Relapse rates appeared better than with

psychopharma-cologic agents.

Summary

There were approximately 22 randomized trials

conducted be-tween 1985 and 1997 involving 1100 children treated

pharma-cologically or behaviorally for primary nocturnal enuresis. The quality

of many of these trials is poor with very few trials com-paring drugs with each

other, or drugs with alarms or other be-havioral interventions, and few having

adequate follow-up pe-riods. Desmopressin and tricyclics appeared equally effective

while on treatment, but this effect was not sustained after treat-ment stopped.

It is clear that further comparisons between drug and behavioral treatments are

needed, and should include relapse rates after treatment is finished.

Assessment and Management of Diurnal Enuresis

Daytime enuresis, although it can occur together

with night-time enuresis, has a different pattern of associations and responds

to different methods of treatment. It is much more likely to be associated with

urinary tract abnormalities and to be comorbid with other psychiatric

disorders. As a result, a more detailed and focused medical and psychiatric

evaluation is indicated. Urine should be checked repeatedly for infection, and

the threshold for ordering ultrasonographical visualization of the urological

sys-tem should be low. The history may make it apparent that the daytime

wetting is situation specific. For example, school-based enuresis in a child

who is too timid to ask to use the bathroom could be alleviated by the teacher’s

tactfully reminding the child to go to the bathroom at regular intervals.

Observation

of children with diurnal enuresis has estab-lished that they do experience an

urge to pass urine before mictu-rition but that either this urge is ignored or

the warning comes too late to be of any use because of an “irritable bladder”.

Therefore, treatment strategies are based on establishing a pattern of

toilet-ing before the times that diurnal enuresis is likely to occur (usu-ally

between 12 noon and 5 pm) and using positive reinforcement to promote regular

use of the bathroom.

Portable systems that can be worn on the body and

use a sensor in the underwear as well as an alarm that can be worn on the wrist

have been developed. Studies have shown no signifi-cant differences between the

wetness alarm and the simple timed alarm. The easiest therapeutic alternative,

therefore, is to buy the child a digital watch with a countdown alarm timer.

Unlike nocturnal enuresis, drug treatment with

tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine is ineffective, whereas the use of

anticholinergic agents such as oxybutynin and terodiline shows a therapeutic

impact on the frequency of daytime enuresis.

Related Topics