Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Elimination Disorders and Childhood Anxiety Disorders

Encopresis

Encopresis

Definition

Encopresis is usually defined as the intentional or

involuntary passage of stool into inappropriate places in the absence of any

identified physical abnormality in children older than 4 years. It may not be

attributable to a medical condition and must occur at least monthly for a

period of three months. The distinction is drawn between encopresis with

constipation (retention with over-flow based on history or physical

examination) and encopresis without constipation. Other classification schemes

include mak-ing a primary–secondary distinction (based on having a 1-year

period of continence) or soiling with fluid or normal feces.

Course and Natural History

Less than one-third of children in the USA have

completed toilet training by the age of 2 years with a mean age of 27.7 months.

Bowel control is usually achieved before bladder control.

The age cutoff for “normality” is set at 4 years,

the age at which 95% of children have acquired fecal continence (Stein and

Susser, 1967). As with urinary continence, girls achieve bowel control earlier

than boys.

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of encopresis in 7- and

8-year-old children has been shown to be 1.5%, with boys (2.3%) affected more

com-monly than girls (0.7%). There was a steadily rising likelihood of continence

with increasing age, until by age 16 years the re-ported prevalence was almost

zero. Rutter and coworkers (1970) reported a rate of 1% in 10- to 12-year-old

children, with a strong (5 : 1) male/female ratio. Retrospective study of

clinic-referred en-copretic children has shown that 40% of cases are primary

(true failure to gain control), with a mean age of 6.7 years, and 60% of cases

are secondary, with a mean age of 8 years (Levine, 1975). Eighty percent of

patients were constipated, with no difference in this feature seen between

primary and secondary subtypes.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Within the first year of life, children can show a tendency toward constipation,with concordance for constipation being six times more frequent in monozygotic than in dizygotic twins. Fecal retention and reduced stool frequency between 12 and 24 months of age can predict later encopresis. Encopretic children with constipation and overflow are found to have rectal and colonic distention, massive impaction with hard feces and a number of specific abnormalities of anorectal physiology. These abnor-malities, which may be primary or secondary to constipation, include elevated anal resting tone, decreased anorectal motility and weakness of the internal anal sphincter, and dysfunction of the external anal sphincter. Encopresis may occur after an acute episode of constipation following illness or a change in diet. In addition to the pain caused by attempts to pass an extremely hard stool, a number of specific painful perianal conditions such as anal fissure can lead to stool withholding and later fecal soiling. Stressful events such as the birth of a sibling or attending a new school have been associated with up to 25% of cases of secondary encopresis. In nonretentive encopresis, the main theories center on faulty toilet training. Stress during the training period, co-ercive toileting leading to anxiety and “pot phobia”, and failure to learn or to have been taught the appropriate behavior have all been implicated. True fecal urgency, which may have a physi-ological or pathological basis, may also be important in a small proportion of cases (Woodmansey, 1967).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

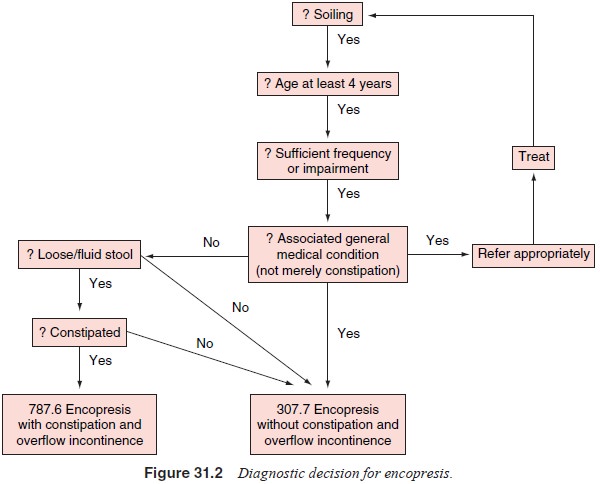

The main efforts during the diagnostic process are

to establish the presence or absence of constipation and, to a lesser extent,

distinguish continuous (primary) from discontinuous (second-ary) soiling

(Figure 31.2). Taylor and Hersov (1994) listed three types of identifiable

encopresis in children: 1) it is known that the child can control defecation,

but she or he chooses to defecate in inappropriate places; 2) there is true

failure to gain bowel con-trol, and the child is unaware of or unable to

control soiling; and 3) soiling is due to excessively fluid feces, whether from

constipa-tion and overflow, physical disease, or anxiety. In practice, there is

frequently overlap among types or progression from one to an-other. Unlike

enuresis, fecal soiling rarely occurs at night or dur-ing sleep, and if

present, is indicative of a poor prognosis. Soiling due to anal masturbation

has been reported, although this causes staining of the sheets rather than full

stools in the bedclothes.

Phenomenology

In the first group, in which bowel control has been

established, the stool may be soft or normal (but different from fluid-type

feces seen in overflow). Soiling due to acute stress events (e.g., the birth of

a sibling, a change of school, or parental separation) is usually brief once

the stress has abated, given a stable home environment and sensible management.

In more severe patho-logical family situations, including punitive management

or frank physical or sexual abuse (Boon, 1991), the feces may be deposited in

places deliberately to cause anger or irritation, or there may be associated

smearing of feces on furniture and walls. Other covert aggressive antisocial

acts may be evident, with considerable denial by the child of the magnitude or

seri-ousness of the problem.

In the second group, in which there is failure to

learn bowel control, a nonfluid stool is deposited fairly randomly in clothes,

at home and at school. There may be conditions such as mental retardation or

specific developmental delay, spina bifida, or cerebral palsy that impair the

ability to recognize the need to defecate and the appropriate skills needed to

defer this function until a socially appropriate time and location. In the

absence of low IQ or pathological physical condition, patients have been

re-ported as having associated enuresis, academic skills problems and

antisocial behavior. They present to pediatricians primarily and are usually

younger (age 4–6 years) than other encopretic individuals. It is thought that

this type of soiling is considerably more common in socially disadvantaged,

disorganized families because of stressful, faulty or inconsistent training.

In the third group, excessively fluid feces are passed, which may result from conditions that cause true diarrhea (e.g., ulcera-tive colitis) or, much more frequently, from constipation with overflow causing spurious diarrhea. A history of retention, either willful or in response to pain, is prominent in the early days of this form of encopresis, although later it may be less apparent be-cause of fecal overflow. Behavior such as squatting on the heels to prevent defecation or marked anxiety about the prospect of using the toilet (although rarely amounting to true phobic avoid-ance) may be described.

Issues and Further Assessment

The comprehensive assessment process should include

a medical evaluation, psychiatric and family interviews, and a systematic

behavioral recording.

The medical evaluation comprises a history, review

of systems, physical examination, and appropriate hematological and

radiological tests. Although the vast majority of patients with encopresis are

medically normal, a small proportion have pathological features of etiological

significance. Physical causes of encopresis without retention include

inflammatory bowel dis-ease (e.g., ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease),

central nervous system disorders, sensory disorders of the anorectal region or

pelvic floor muscles (e.g., spina bifida, cerebral palsy). Organic causes of

encopresis with retention include Hirschsprung’s dis-ease (aganglionosis in

intermuscular and submucous plexuses of the large bowel extending proximally

from the anus), neurogenic megacolon, hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia, chronic

codeine or laxative usage, anorectal stenosis and fissure. It should also be

remembered that these conditions rarely have their first presenta-tion with

encopresis alone.

The physical assessment should include an abdominal

and rectal examination, although a plain abdominal radiograph is the most

reliable way to determine the presence of fecal impaction. Anorectal manometry

should be considered in the investigation of children with severe constipation

and chronic soiling, espe-cially those in whom Hirschsprung’s disease is

suspected.

Psychiatric and family interviews should include a

devel-opmental history and a behavioral history of encopresis (ante-cedents,

behavior and consequences). Specific areas of stress, acute or chronic,

affecting the child or family, or both, should be discovered. Associated

psychopathological conditions are more commonly found in the older child, in

secondary encopresis, and when soiling occurs not only in clothes. Anxiety

surrounding toileting may indicate pot phobia, coercive toileting, or a

his-tory of painful defecation. A history should be obtained of the parents’

previous attempts at treatment together with previously prescribed therapy so

that reasons for previous failure can be identified and anticipated in future

treatment planning.

Treatment

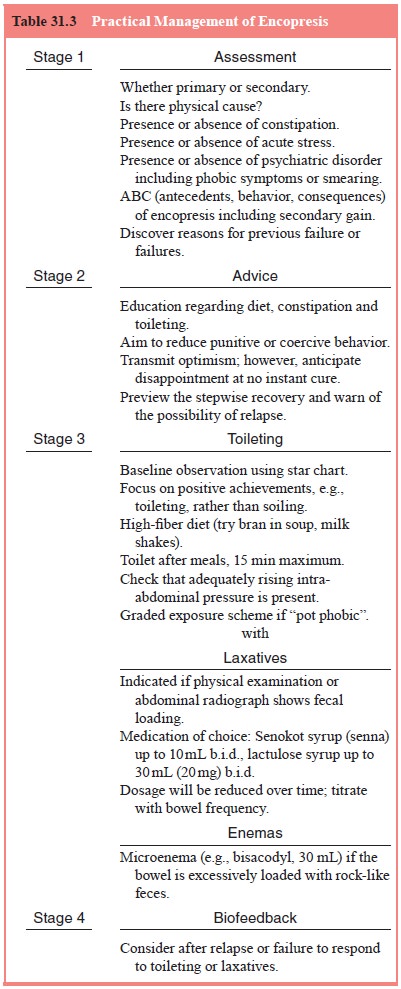

Practical management for encopresis is presented in

Table 31.3.

Standard Treatment

The principal approach to treatment is predicated

on the results of the evaluation and the clinical category assigned. This

differenti-ates between the need to establish a regular toileting procedure in

patients in whom there has been a failure to learn this social behavior and the

need to address a psychiatric disorder, par-ent–child relationship

difficulties, or other stresses in the child who exhibits loss of this

previously acquired skill in association with these factors. In both cases,

analysis of the soiling behavior may identify reinforcing factors important in

maintaining dys-function. Detection of significant constipation will, in

addition, provide an indication for adjuvant laxative therapy.

Behavioral Treatments

Behavioral therapy is the mainstay of treatment for encopresis. In the younger child who has been toilet trained, this focuses on practical elimination skills, for example, visiting the toilet after each meal, staying there for a maximum of 15 minutes, using muscles to increase intra-abdominal pressure and cleaning one-self adequately afterward. Parents or caretakers, or both, need to be educated in making the toilet a pleasant place to visit and should stay with the younger child, giving encouragement and praise for appropriate effort. Small children whose legs may dangle above the floor should be provided with a step against which to brace when straining. Initially, a warm bath before us-ing the toilet may relax the anxious child and make it easier to pass stool. Systematic recording of positive toileting behavior, not necessarily being clean (depending on the level of baseline behavior), should be performed with a personal star chart. For the child with severe anxiety about sitting on the toilet, a graded exposure scheme may be indicated.

Role of the Family in Treatment

Removing

the child’s and family’s attention from the encopresis alone and focusing onto

noticing, recording and rewarding positive behavior often defuses tension and

hostility and provides the opportunity for therapeutic improvement. Identifying

and eliminating sources of secondary gain, whereby soiling is reinforced by

parental (or other individuals’) actions and attention, even if negative or

punitive, make positive efforts more fruitful. Some investigators advocate mild

punishment techniques, such as requiring the child to clean his or her own

clothes after soiling, although care must be taken to prevent this from

becoming too punitive. In certain settings, particularly school, attempts are

made to prevent soiling by extremely frequent toileting that, although keeping

the child clean, does not promote and may even hinder the acquisition of a

regular bowel habit. Formal therapy, either individual or family based, is

indicated in only a minority of patients with an associated psychiatric

disorder, marked behavioral disturbance, or clear remediable family or social

stresses.

Physical Treatments

In

patients with retention leading to constipation and overflow, medical

management is nearly always required, although it is usually with oral

laxatives or microenemas alone. The use of more intrusive and invasive colonic

and rectal washout or sur-gical disimpaction procedures is nearly always the

result of the clinician’s impatience rather than true clinical need.

Uncontrolled

studies of combined treatment with behav-ioral therapy and laxatives reported

marked improvement in symptoms (not cure) in approximately 70 to 80% of

patients. A more recent controlled randomized trial (Nolan et al., 1991) com-paring behavioral therapy in retentive primary

encopresis with and without laxatives showed that at 12-month follow-up, 51% of

the combined treatment (laxative plus behavioral therapy) group had achieved

remission (at least one 4-week period with no soil-ing episodes), compared with

36% of the behavioral therapy only group (P

5 0.08).

Partial remission (soiling no more than once a week) was achieved in 63% of

patients with combined therapy versus 43% with behavioral therapy alone (P 5 0.02). Patients receiving

laxatives achieved remission significantly sooner, and the difference in the

Kaplan–Meier remission curves was most striking in the first 30 weeks of

follow-up (P 5 0.012).

When patients who were not compliant with the toileting program were removed

from the analysis, however, the advantage of combined therapy was not

significant. These results must also be viewed in light of a 50% spontaneous

remission rate at 2 years reported in some studies.

Biofeedback Therapy

The

finding that some children with treatment-resistant retentive encopresis

involuntarily contract the muscles of the pelvic floor and the external anal

sphincter, effectively impeding passage of stool, has led to efforts to use

biofeedback in this instance. It has similarly been reported that as few as six

sessions of bio-feedback therapy can lead to a significant reduction in symptom

frequency for as many as 86% of previously treatment-resistant patients

(Loening-Baucke, 1995). It is possible, however, that bio-feedback is

principally of benefit to nonretentive chronic soilers (van Ginkel et al., 2000).

Related Topics